The Athletic Department and the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

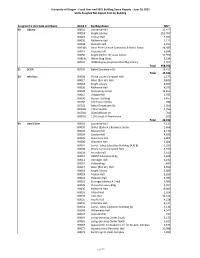

June 30, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet by Building

University of Oregon - Fiscal Year-end 2021 Building Space Reports - June 30, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet by Building Assigned To Unit Code and Name BLDG # Building Name NSF* 20 Library B0001 Lawrence Hall 12,447 B0018 Knight Library 261,767 B0019 Fenton Hall 7,924 B0030 McKenzie Hall 1,112 B0038 Klamath Hall 3,012 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 24,383 B0047 Cascade Hall 6,994 B0050 Knight (Wllm. W.) Law Center 31,592 B0814L White Stag Block 5,534 B0903 OIMB Rippey (Loyd and Dorothy) Library 3,997 Total 358,762 21 SCUA B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 15,422 Total 15,422 30 Info Svcs B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 1,375 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,826 B0018 Knight Library 8,305 B0030 McKenzie Hall 4,973 B0039 CompUting Center 13,651 B0042 Oregon Hall 2,595 B0090 Rainier BUilding 3,457 B0156 Cell Tower Utility 288 B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 1,506 B0726L 1715 Franklin 1,756 B0750L 1600 Millrace Dr 700 B0891L 1199 SoUth A WarehoUse 500 Total 42,932 99 Genl Clsrm B0001 Lawrence Hall 7,132 B0002 Chiles (Earle A.) BUsiness Center 2,668 B0003 Anstett Hall 3,176 B0004 Condon Hall 4,696 B0005 University Hall 6,805 B0006 Chapman Hall 3,404 B0007 Lorry I. Lokey EdUcation BUilding (A & B) 2,016 B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 6,339 B0009 Friendly Hall 2,610 B0010 HEDCO EdUcation Bldg 5,648 B0011 Gerlinger Hall 6,192 B0015 Volcanology 489 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 4,650 B0018 Knight Library 5,804 B0019 Fenton Hall 3,263 B0022 Peterson Hall 3,494 B0023 Esslinger (ArthUr A.) Hall 3,965 B0029 Clinical Services Bldg 2,467 B0030 McKenzie Hall 19,009 B0031 Villard Hall 1,924 B0034 Lillis Hall 24,144 B0035 Pacific Hall 4,228 B0036 ColUmbia Hall 6,147 B0041 Lorry I. -

Eugene, Cascades & Coast | OREGON

Eugene, Cascades & Coast | OREGON Welcome to Eugene, Cascades & Coast, sports mecca of the Pacific Northwest! Steeped in sports tradition and excellence, we offer multipurpose indoor and outdoor venues, turf and grass fields, and natural outdoor venues with enough flexibility to support most events. Ample, friendly and affordable hotel options, no sales tax and strong local support for all sports makes us the perfect sports destination! PK Park Eugene, Oregon Need Assistance? Once you have selected the Eugene, Cascades & Coast region as your sports event destination, our Sports Services Department will be ready to assist you in planning a successful event. Our experienced staff offers a comprehensive array of services, most of which are complimentary. Promotional materials available include visitor guides, maps, video presentations, high-resolution images, customer web pages and web links for participants. Courtesy of Matthew Knight Arena & UO • Assistance in arranging ground transportation, centralized accommodations and auxiliary space for team meetings, meals and expos. Utilize our knowledge of local vendors for the best referrals from food vendors to printing services. • Permit application guidance • Access to our extensive database of volunteers and local officials • Knowledge of local resources available for use including walkie-talkies, fencing, signs,etc. • Pre- and post-event activities, suggestions and referrals Willamalane Swim Club by Matt Nicholson For personalized assistance, contact Sue Harshbarger Director of Sports Sales & Development [email protected] 541.743.8755 Eugene 08 by Dave Thomas Eugene, Cascades & Coast Sports • 754 Olive St • Eugene OR 97401 • 541.743.8755 • 800.547.5445 • EugeneCascadesCoast.org/sports (US & Canada) Eugene, Cascades & Coast | OREGON Savor Eugene, Cascades & Coast! Soak up the Northwest’s Did you know? laid-back culture with stress-free transportation, affordable • Matthew Knight Arena opened in adventures, plentiful entertainment and authentic experiences. -

Brooks: with Ruffled Ducks Ahead, Buffs Can't Mope

2/11/13 Brooks: With Ruffled Ducks Ahead, Buffs Can’t Mope - CUBuffs.com - Official Athletics Web site of the University of Colorado CU senior Sabatino Chen says the Buffs must have sense of urgency over last nine games. Photo Courtesy: Joel Broida Brooks: With Ruffled Ducks Ahead, Buffs Can’t Mope Release: 02/06/2013 Courtesy: B.G. Brooks, Contributing Editor BOULDER - For most coaches, moving past losses usually requires a couple of days, provided they have a couple to spare. For Tad Boyle, getting rid of last weekend's loss at Utah appeared more of a chore - or so it seemed late Monday Game Notes at Oregon afternoon. He converses weekly (maybe daily during some weeks) with Maryland coach Mark Turgeon, a close friend, mentor and former boss. That Boyle spoke by phone with Turgeon following Colorado's insipid, uninspired 58- 55 loss on Saturday in Salt Lake City was as predictable as discord in Congress. Turgeon's advice to Boyle might seem generic, but after feeling CU's three-game winning streak crumpled and discarded by the Pac-12 Conference's last-place team, any words offered by a colleague/friend were appreciated. Turgeon to Boyle: "Don't get too high, don't get too low; stay even-keeled. That's what he said, and he's right. There were some things I was contemplating that I didn't do (in SLC). But I want our players to understand that the effort and the level of concentration, the level of focus and the level of execution that we displayed against Utah are unacceptable. -

Weed and Banking

LOCALLY OWNED AND OPERATED HAPPY CANNABIS ISSUE! - WE’LL BE YOUR SPOT ALL WEEK FOR - DANK FLOWER SPECIALS 30% OFF ALL REGULAR SHELF BUD COME TRY OUR FINEST STRAINS FOR BUDGET PRICES! $30 OUNCES, AND $3 GRAMS OF SELECT FLOWER, TAX INCLUDED! WHILE SUPPLIES LAST & DOPE DEALS ON CONCENTRATES $10 GRAMS OF SHATTER TAX INCLUDED! WHILE SUPPLIES LAST & $5O ELITE SELECT STRAIN PENTOPS ONLY AT EUGREEN HEALTH CENTER HIGHEST QUALITY LOWEST PRICES SPECIALS VALID MAY 3, 2018 - MAY 9, 2018 Do not operate a vehicle or machinery under the influence of this drug. For use by adults twenty one years of age and older. Keep out of the reach of children. 2 May 3, 2018 • eugeneweekly.com CONTENTS May 3-9, 2018 4 Letters 6 News 10 Slant 12 Cannabis 20 Calendar 29 Movies 30 Music 36 Classifieds 39 Savage Love MISSY SUICIDE WHO YOU GONNA BLAME? editorial Editor Camilla Mortensen Arts Editor Bob Keefer Senior Staff Writer Rick Levin Staff Writer/Web Editor Meerah Powell Calendar Editor Henry Houston Copy Editor Emily Dunnan Social Media Athena Delene Contributing Editor Anita Johnson Contributing Writers Blake Andrews, Ester Barkai, Aaron Brussat, Brett Campbell, Rachael Carnes, Tony Corcoran, Alexis DeFiglia, Jerry Diethelm, Emily Dunnan, Rachel Foster, Mark Harris, William Kennedy, Paul Neevel, Kelsey Anne Rankin, Carl Segerstrom, Ted Taylor, Molly Templeton, Max Thornberry, David Wagner, Robert Warren Interns Taylor Griggs, Taylor Perse Art Department Art Director/Production Manager Todd Cooper Technology/Webmaster James Bateman Graphic Artists Sarah Decker, Chelsea -

Upcoming Eugene Events 2015 Courtesy Reminder on Behalf Of: Hilton Eugene

Upcoming Eugene Events 2015 Courtesy Reminder on Behalf of: Hilton Eugene Eugene Saturday Market Downtown Eugene's First Friday ArtWalk Date(s): Apr 04, 2015 – Nov 14, 2015 Date(s): Jun 05, 2015 – Jul 02, 2015 Recurrence: Every Saturday Recurrence: Recurring daily Times: Saturdays, 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Times: Daily Location: Downtown Park Blocks (a block away from the Location: Downtown Eugene Hilton) Address: 5th Street to Broadway, Eugene, OR 97401 Address: 126 E. 8th, Eugene, OR 97401 Admission: Free Admission: Free Contact: 541.485.2278 Contact: 541.686.8885 Website: Visit Website Website: Visit Website See displays from local artists all month long at downtown Saturday Market is a weekly celebration of local arts, food, Eugene galleries from 5th Street to Broadway. Visit music and everything Eugene. Over 250 artisans sell their MODERN (207 E 5th Ave), Studio Mantra Salon (40 E 5th handcrafted goods, 16 food booths serve up an international Ave), Belle Sorelle (488 Willamette St), The Lincoln Gallery array of foods, and the stage features 6 live music acts each (309 W 4th Ave), Area 51/50 Clothing (277 W 8th Ave), day. Open rain or shine, in a beautiful park setting. and Raven Frameworks Inc. (325 W 4th Ave). Annual Barrel Tour NCAA Outdoor Track & Field Championships Date(s): Jun 06, 2015 – Jun 20, 2015 Date(s): Jun 10, 2015 – Jun 13, 2015 Recurrence: Every Saturday Recurrence: Recurring daily Times: Saturday Times: Wednesday - Saturday, TBA Location: South Willamette Wineries Association Location: Hayward Field Venue: South Willamette Wineries Association Venue: Hayward Field Admission: TBD Address: 15th and Agate Street, Eugene, OR 97403 Website: Visit Website Admission: Varies Welcome to the Annual Barrel Tour, featuring three unique The nation's best Division I collegiate Track and Field tours of the South Willamette Valley Wineries. -

Duck Men's Basketball

ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS (MBB) Greg Walker [email protected] O: 541-346-2252 C: 541-954-8775 Len Casanova Center | 2727 Leo Harris Parkway | @OregonMBB | Facebook.com/OregonMBB | GoDucks.com 2020-21 SCHEDULE DUCK MEN’S BASKETBALL NOVEMBER RESULT SCORE No. 21 OREGON (9-2, 4-1) vs. OREGON STATE (7-5, 3-3) 25 Eastern Washington PPD PPD Date Saturday, January 23, 2021 Tip Time 7:35 p.m. PT DECEMBER RESULT SCORE Site / Stadium / Capacity Eugene, Ore. / Matthew Knight Arena / 12,364 2 vs. Missouri 1 L 75-83 Television Pac-12 Network 4 vs. Seton Hall 1 W 83-70 Ted Robinson, play-by-play; Don MacLean, analyst Radio Oregon Sports Network (95.3 FM KUJZ in Eugene/Springfi eld) 7 Eastern Washington W 69-52 Joey McMurry, play-by-play; Jerry Allen, analyst 9 Florida A&M W 87-66 Live Stats GoDucks.com Live Audio GoDucks.com 12 at Washington * W 74-71 Twitter @OregonMBB 17 San Francisco W 74-64 Internet tunein.com 19 Portland W 80-41 Satellite Radio Sirius ch. 146 / XM ch. 197 / Internet 959 23 UCLA * PPD PPD SERIES HISTORY 31 California * W 82-69 All-Time Oregon State leads, 190-164 Last Meeting Oregon 69, Oregon State 54, Feb. 27, 2020 (Eugene, Ore.) JANUARY TIME TV Current Streak Ducks +1 2 Stanford * W 73-56 Last Oregon Win Oregon 69, Oregon State 54, Feb. 27, 2020 (Eugene, Ore.) Last OSU Win Oregon State 63, Oregon 53, Feb. 8, 2020 (Corvallis, Ore.) 7 at Colorado * L 72-79 9 at Utah * W 79-73 THE STARTING 5 14 Arizona State * PPD PPD 16 Arizona * PPD PPD No. -

11 Units ASF Occupied by Bldg FY21

University of Oregon - Fiscal Year-end 2021 Building Space Reports - June 30th, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet Occupied by Building Assigned To Unit Code and Name Loaned To Unit Code and Name BLDG # Building Name NSF* 20 Library . B0001 Lawrence Hall 12,447 B0018 Knight Library 257,306 B0019 Fenton Hall 7,924 B0030 McKenzie Hall 1,112 B0038 Klamath Hall 2,412 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 23,905 B0047 Cascade Hall 6,994 B0050 Knight (Wllm. W.) Law Center 31,592 B0814L White Stag Block 5,534 B0903 OIMB Rippey (Loyd and Dorothy) Library 3,997 701 CIS B0038 Klamath Hall 600 1513 Cinema StUdies B0018 Knight Library 2,575 7330 Univ HoUsing B0018 Knight Library 194 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 478 7475 TAE Center B0018 Knight Library 916 9801 OR Folklife B0018 Knight Library 776 Total 358,762 21 SCUA . B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 15,422 Total 15,422 30 Info Svcs . B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 1,375 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,826 B0018 Knight Library 7,683 B0030 McKenzie Hall 4,973 B0039 CompUting Center 13,651 B0042 Oregon Hall 2,595 B0090 Rainier BUilding 3,457 B0156 Cell Tower Utility 288 B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 1,506 B0726L 1715 Franklin 1,756 B0750L 1600 Millrace Dr 700 B0891L 1199 SoUth A WarehoUse 500 1513 Cinema StUdies B0018 Knight Library 622 Total 42,932 99 Genl Clsrm . B0001 Lawrence Hall 5,702 B0002 Chiles (Earle A.) BUsiness Center 1,107 B0003 Anstett Hall 3,176 B0004 Condon Hall 3,667 B0005 University Hall 6,805 B0006 Chapman Hall 1,820 B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 5,987 B0009 Friendly Hall 1,623 B0010 HEDCO EdUcation Bldg 2,258 B0011 Gerlinger Hall 5,356 B0015 Volcanology 489 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,352 B0018 Knight Library 3,424 B0019 Fenton Hall 2,740 B0022 Peterson Hall 3,494 B0023 Esslinger (ArthUr A.) Hall 3,965 B0029 Clinical Services Bldg 1,878 B0030 McKenzie Hall 16,902 B0031 Villard Hall 1,924 B0034 Lillis Hall 11,122 B0035 Pacific Hall 3,392 B0036 ColUmbia Hall 6,147 B0041 Lorry I. -

Vvyx Network Connectivity Owned Network Leased Network

Vyvx Availability at North American Sports Venues Vvyx Network connectivity Edmonton Owned Network Leased Network Calgary ANAHEIM, CA Angel Stadium SACRAMENTO, CA Honda Center Sleep Train Arena Winnipeg ARLINGTON, TX Vancouver ST. LOUIS, MO AT&T Stadium Busch Stadium Globe Life Park in Arlington Scottrade Center ATLANTA, GA ST. PAUL, MN Georgia Dome Xcel Energy Center Turner Field Seattle Philips Arena ST. PETERSBURG, FL McCamish Pavilion Tropicana Field Bobby Dodd Stadium SALT LAKE CITY, UT AUSTIN, TX Vivint Smart Home Arena D K Royal - Texas Memorial Stadium Rio Tinto Stadium Ottawa Montreal Portland Huntsman Center BALTIMORE, MD Minneapolis St. Paul Rice Eccles Stadium M&T Bank Stadium Green Bay Oriole Park at Camden Yards Corvalis SAN ANTONIO, TX Eugene AT&T Center BATON ROUGE, LA Toronto Alamodome Alex Box Stadium Tiger Stadium Milwaukee SAN DIEGO, CA Maravich Center Buffalo Qualcomm Stadium Boston Petco Park BOSTON, MA Detroit Fenway Park Hartford SANTA CLARA, CA Iowa City Chicago Providence Gillette Stadium Omaha Levi’s Stadium Cleveland TD Garden South Bend East Rutherford Uniondale Lincoln SAN FRANCISCO, CA BOULDER, CO Salt Lake City Newark AT&T Park Columbus State College New York Folsom Field Boulder Indianapolis Coors Event Center Pittsburgh SAN JOSE, CA Philadelphia SAP Center Denver Kansas City BUFFALO, NY Cincinnati Baltimore Avaya Stadium Ralph Wilson Stadium Sacramento First Niagara Center Washington, D.C. SEATTLE, WA St. Louis Louisville San Francisco CenturyLink Field CALGARY, ALBERTA Oakland Charlottesville Safeco Field -

Ducks to Close Regular Season at Arizona State

OREGON MEDIA SERVICES Chris Geraghty Assistant Director (MBB) Work: 541.346.7332 | Cell: 541.335.9158 2727 Leo Harris Parkway • Eugene, Oregon • 97401 • 541-346-5488 (P) • 541-346-5449 (F) • www.GoDucks.com e-mail: [email protected] GAMES 29-30 • ASU-ARIZ • MARCH 3-5 OREGON MEN’S BASKETBALL 2010-11 OREGON SCHEDULE (14-14, 7-9) DUCKS TO CLOSE REGULAR SEASON NOVEMBER 5 Northwest Christian (EXHIBITION) W, 80-53 AT ARIZONA STATE, ARIZONA ----- BTI Invitational ----- EUGENE, Ore. March 2, 2011 12 North Dakota State # W, 97-92 (ot) The University of Oregon men’s basketball team (14-14, 7-9) will close out the regular-season 13 Denver # W, 68-56 schedule on the road this week against Arizona State (10-18, 2-14) and Arizona (23-6, 12-4). Thurs- 14 UC Santa Barbara # W, 72-70 day’s UO-ASU contest is set for 5:30 p.m. (PT) at Wells Fargo Arena in Tempe, while the Ducks-Wild- 20 San Jose State L, 72-75 cats contest on Saturday is scheduled for 11 a.m. (PT) at McKale Center in Tucson. 23 Texas Southern W, 75-52 Oregon is coming off a pair of home losses, falling 81-71 to California last Thursday and an 88-71 27 vs. No. 1 Duke $ L, 71-98 loss to Stanford on Saturday. Arizona lost both games last week, a 65-57 defeat at USC and a 71-49 loss to UCLA. Arizona State also dropped a pair of games, a 71-53 result at UCLA and 62-46 at USC. -

Oregon Alpha News 07

Oregon Alpha News Sigma Alpha Epsilon at Oregon State University Volume 90, No. 1 2929 NW Harrison Blvd., Corvallis, Oregon 97330 July 2011 John Masterson ’61 with undergraduates Valley Football Center at Reser Stadium. While at the house prior to the celebration, I noticed the original plaque was still in place, although, as one might suspect, the wood was aging and not in the best condition. It was at that time that I Oregon Alpha: A Tale of Two Plaques suggested to Bill Brennan, Chris Langton and Dick Thompson that a new solid A new SAE house was dedicated in working experience, I volunteered to ac- bronze plaque be made. The old crest was the fall term of 1959. There was an open- complish this task. I was a junior at the sent to me in Long Beach, and I had a ing approximately 22" x 18" that was left time. This first plaque was a plain piece design initiated from a bronze plaque in the front brick wall for a recognition of alder wood with the polished crest maker in Southern California. The design plaque. However, no design or descrip- mounted in the center. Once completed, incorporated the original crest. The new tion of such a plaque was prepared by photographs were taken of George A. plaque was completed, and Chris Langton the planners or architects. A few weeks Powell ’21 and other notables holding installed it at the house in September 2010. before the dedication of the house, some the plaque in place at the front of the of the local alumni discovered we had a house. -

Looming Cuts May Have Silver Lining a SCHOOL ON

Lamb’sLa chops YOUR ONLINE LOCAL Head Hawk PortlandPor sax man Patrick DAILY NEWS Travis Green scores as fi ll-in LamLamb gets funky with ‘Maceo!’ www.portlandtribune.com lead coach of Winterhawks Portland— See LIFE, B1 Tribune— See SPORTS, B10 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2013 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDAILY PAPER • WWW.PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COM • PUBLISHED THURSDAY ■ Nike documentary about Jefferson basketball ignites school spirit, pride TRIBUNE PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER ONSTOTT Former Dotty’s manager Patrick Burns handled several thousand dollars a day in cash at the lottery deli, and sued when the company charged him for cash shortfalls. His lawyer argues the practice violated the state minimum wage law. Lawsuit slams Dotty’s ‘kickback’ Class-action fi ling says lottery deli broke TRIBUNE PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER ONSTOTT minimum-wage laws Jefferson sophomore basketball player Dario Papa-Vicente takes a moment to pray before the Democrats’ Feb. 19 home rivalry match against Benson Tech. One of fi ve high schools sponsored by Nike’s Jordan Brand, Jefferson’s basketball program is the subject of a documentary project in the works. By STEVE LAW The Tribune A Portland attorney is su- ing the state’s largest lottery A SCHOOL ON THE retailer, alleging that it rou- tinely violated Oregon’s minimum wage law. Attorney Paul Breed claims that Oregon Restaurant Ser- vices Inc., which owns the lu- crative Dotty’s deli chain, ille- gally forced minimum-wage REBOUND employees to pay “kickbacks” to cover shortages in the cash ilas Melson likes school all ball in the community during the register at the end of their right. -

Downtown Eugene, Oregon Final Report

DOWNTOWN EUGENE, OREGON PEDESTRIAN WAYFINDING MASTER PLAN July 1, 2015 Revised: October 16, 2015 FINAL REPORT MERJE | ENVIRONMENTS & EXPERIENCES Julie Jenson 120 North Church Street Graphic Space Suite 208 2844 Edgewater Dr. West Chester, PA 19380 Eugene, OR T 484.266.0648 97401 www.merjedesign.com 503-545-4968 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 6 Objectives and Philosophy 7 Project Approval Process Section 1 Wayfinding Tools 10 Wayfinding Tools 11 Pre-Arrival Technology 12 Place Technology 13 ibeacon 14 Orientation Maps 16 Landmarks 17 Streetscape Elements 18 Existing Visitors Info 19 Existing Signage Evaluation Section 2 Wayfinding & Signage Analysis 22 Information Hierarchy 23 Highway Signage: I-90 24 Arrival and Gateways 25 Districts 26 Destinations 27 Pedestrian Terminologies 28 Public Parking Routes 29 Public Parking Considerations 31 Public Parking Existing Conditions 36 Pedestrian Starting-points 37 Pedestrian Information Hubs 38 Information Hubs 39 Generic Menu of Sign Types 40 Bicycle Information 41 Banner Strategy 42 Art Link Section 3 Strategies 46 Sample Criteria for Inclusion 48 Criteria for Inclusion - Wayfinding Tiers 49 Phasing Plan 50 Management & Maintenance 52 Sustainability Materials & Process 53 Measurements Section 4 Design Criteria 56 Pedestrian Sign Design Criteria 57 Inspiration 58 Design Concepts July 1, 2015 | EUGENE, OREGON – Pedestrian Wayfinding and Programming Analysis TABLE OF CONTENTS WAYFINDING TOOLS3 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The team would like to thank a number Assistance of people and organizations