Case of Diana Abujber's Arabian Jazz (2003) and Fadia Faqir's My Name Is Salma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People's Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga in Pakhtun Socıety

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 8(1)180-183, 2018 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2018, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com People’s Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga ın Pakhtun Socıety Muhammad Nisar* 1, Anas Baryal 1, Dilkash Sapna 1, Zia Ur Rahman 2 Department of Sociology and Gender Studies, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 1 Department of Computer Science, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 2 Received: September 21, 2017 Accepted: December 11, 2017 ABSTRACT “This paper examines the institution of Jirga, and to assess the perceptions of the people regarding Jirga in District Malakand Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A sample of 12 respondents was taken through convenience sampling method. In-depth interview was used as a tool for the collection of data from the respondents. The results show that Jirga is deep rooted in Pashtun society. People cannot go to courts for the solution of every problem and put their issues before Jirga. Jirga in these days is not a free institution and cannot enjoy its power as it used to be in the past. The majorities of Jirgaees (Jirga members) are illiterate, cannot probe the cases well, cannot enjoy their free status as well as take bribes and give their decisions in favour of wealthy or influential party. The decisions of Jirgas are not fully based on justice, as in many cases it violates the human rights. Most disadvantageous people like women and minorities are not given representation in Jirga. The modern days legal justice system or courts are exerting pressure on Jirga and declare it as illegal. -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment -

Path(S) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community”

“Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” By Jaison Carter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair Professor Charles Hirschkind Professor Stefania Pandolfo Professor Ula Y. Taylor Spring 2018 Abstract “Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” by Jaison Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair The Mustafawiyya Tariqa is a regional spiritual network that exists for the purpose of assisting Muslim practitioners in heightening their level of devotion and knowledges through Sufism. Though it was founded in 1966 in Senegal, it has since expanded to other locations in West and North Africa, Europe, and North America. In 1994, protegé of the Tariqa’s founder and its most charismatic figure, Shaykh Arona Rashid Faye al-Faqir, relocated from West Africa to the United States to found a satellite community in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. This location, named Masjidul Muhajjirun wal Ansar, serves as a refuge for traveling learners and place of worship in which a community of mostly African-descended Muslims engage in a tradition of remembrance through which techniques of spiritual care and healing are activated. This dissertation analyzes the physical and spiritual trajectories of African-descended Muslims through an ethnographic study of their healing practices, migrations, and exchanges in South Carolina and in Senegal. By attending to manner in which the Mustafawiyya engage in various kinds of embodied religious devotions, forms of indebtedness, and networks within which diasporic solidarities emerge, this project explores the dispensations and transmissions of knowledge to Sufi practitioners across the Atlantic that play a part in shared notions of Black Muslimness. -

Ethnographic Atlas of Rajasthan

PRG 335 (N) 1,000 ETHNOGRAPHIC ATLAS OF RAJASTHAN (WITH REFERENCE TO SCHEDULED CASTES & SCHEDULED TRIBES) U.B. MATHUR OF THE RAJASTHAN STATISTICAL SERVICE Deputy Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan. GANDHI CENTENARY YEAR 1969 To the memory of the Man Who spoke the following Words This work is respectfully Dedicated • • • • "1 CANNOT CONCEIVE ANY HIGHER WAY OF WORSHIPPING GOD THAN BY WORKING FOR THE POOR AND THE DEPRESSED •••• UNTOUCHABILITY IS REPUGNANT TO REASON AND TO THE INSTINCT OF MERCY, PITY AND lOVE. THERE CAN BE NO ROOM IN INDIA OF MY DREAMS FOR THE CURSE OF UNTOUCHABILITy .•.. WE MUST GLADLY GIVE UP CUSTOM THAT IS AGA.INST JUSTICE, REASON AND RELIGION OF HEART. A CHRONIC AND LONG STANDING SOCIAL EVIL CANNOT BE SWEPT AWAY AT A STROKE: IT ALWAYS REQUIRES PATIENCE AND PERSEVERANCE." INTRODUCTION THE CENSUS Organisation of Rajasthan has brought out this Ethnographic Atlas of Rajasthan with reference to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. This work has been taken up by Dr. U.B. Mathur, Deputy Census Superin tendent of Rajasthan. For the first time, basic information relating to this backward section of our society has been presented in a very comprehensive form. Short and compact notes on each individual caste and tribe, appropriately illustrated by maps and pictograms, supported by statistical information have added to the utility of the publication. One can have, at a glance. almost a complete picture of the present conditions of these backward communities. The publication has a special significance in the Gandhi Centenary Year. The publication will certainly be of immense value for all official and Don official agencies engaged in the important task of uplift of the depressed classes. -

Language and Ethnic Identity in a Multi-Ethnc High School in Wales

LANGUAGE AND ETHNIC IDENTITY IN A MULTI- ETHNC HIGH SCHOOL IN WALES A case study A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences Cardiff University Author: Hayat Graoui July 2019 Acknowledgements All praise be to Allah whose providence blessed my steps throughout this research project from start to finish, and peace and blessings be upon Mohammed, his last messenger. Words have very often failed me throughout the process of writing this thesis, but they seem even harder to find when trying to acknowledge the kind contribution of people whose support shored up my research journey and helped to bring this project to light. Thank you mum and dad! Every letter and breath in this work was graced with the belief you always had in me. You both are hardly able to read or write, but knew very well how to teach me the value of education and the power of words. Mum, I’m sorry I could only cry and pray when your disease came by, I love you and miss you every day, and I’m so sorry we never had a proper goodbye when I left that day. May you live longer dad, even if all you could recall of now me is taking me to school holding my hand. I wish you could understand that I am doing well and hope that I have made you both proud. I am deeply grateful to my supervisors, Dr Raya Jones and Dr Dawn Mannay, for helping me identify my skills and for consistently increasing my potential to grasp difficult ideas. -

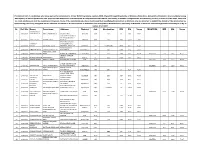

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Intrafamily Femicide in Defence of Honour: the Case of Jordan

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol22, No 1, pp 65 – 82, 2001 Intrafamilyf emicidein de fenceo f honour:the case o fJordan FADIA FAQIR ABSTRACT This article deals with the issue of honourkillings, aparticular type of intrafamily femicide in defenceof honourin Jordan.The legal, social, religious, nationalist andtribal dimensionsand arguments on such killings are presented.Drawing on Arabic and English source material the role ofrumour, social values andother dynamicsin normalisingthis practice in Jordantoday is analysed.Honour killings, whichcontradict manyinternational andnational laws andcovenants, are clearly connectedto the subordinationof womenin Jordanand to the ‘criming down’of domestic violence.The prevailing discrim- inatory culture cannotchange without implementing a comprehensivepro- grammefor socio-legal andpolitical reform. The debateon harm Scholarlyconcentration on harm to womenhas beencriticised recently bymany feminists, whoargue that the debatefocuses solely onviolence, victimisation andoppression of women. 1 TheArab world, however, has notreached the stage wherea similar debateis possible becausedocumentation of and discussion aboutviolence against womenare still in the infancystage. Suchdebates within the Anglo-Saxoncontext, theref ore,do not seem relevant in their entirety to Arabwomen’ s experiences,since most suchwomen are still occupantsof the domestic, private space.Other Western theories, models andanalysis, however, canbe transferred andapplied (with caution)to the Arabexperience of gender violence,which is still largely undocumented. Whatis violence againstwomen? Violenceis the use ofphysical forceto inict injuryon others,but this denition couldbe widened to includeimproper treatment orverbal abuse. It takes place atmacrolevels, amongnation states andwithin communities, andat micro levels within intimate relationships. Theuse ofviolence to maintain privilege turned graduallyinto ‘the systematic andglobal destruction ofwomen’ , 2 orfemicide, 3 with the institutionalisation ofpatriarchy over the centuries. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

Arabic Books Published in India an Annotated Bibliography

ARABIC BOOKS PUBLISHED IN INDIA AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBRARY SCIENCE 1986-86 BY ISHTIYAQUE AHMAD Roll No, 85-M. Lib. Sc.-02 Enrolment No. S-2247 Under the Supervision of Mr. AL-MUZAFFAR KHAN READER DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1986 ,. J^a-175 DS975 SJO- my. SUvienJU ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is not possible for me to thank adequately prof, M.H. Rizvi/ University Librarian and Chairman Department of Library Science. His patronage indeed had always been a source of inspiration, I stand deeply indebted to my supervisor, Mr. Al- Muzaffar Khan, Reader, Department of Library Science without whom invaluable suggestions and worthy advice, I would have never been able to complete the work. Throughout my stay in the department he obliged me by unsparing help and encouragement. I shall be failing in my daties if I do not record the names of Dr. Hamid All Khan, Reader, Department of Arabic and Mr, Z.H. Zuberi, P.A., Library of Engg. College with gratitude for their co-operation and guidance at the moment I needed most, I must also thank my friends M/s Ziaullah Siddiqui and Faizan Ahmad, Research Scholars, Arabic Deptt., who boosted up my morals in the course of wtiting this dis sertation. My sincere thanks are also due to S. Viqar Husain who typed this manuscript. ALIGARH ISHl'ltAQUISHTIYAQUE AAHMA D METHODOLOBY The present work is placed in the form of annotation, the significant Arabic literature published in India, The annotation of 251 books have been presented. -

Badal a Culture of Revenge the Impact of Collateral Damage on Taliban Insurgency

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2008-03 Badal a culture of revenge the impact of collateral damage on Taliban insurgency Hussain, Raja G. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/4222 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS BADAL: A CULTURE OF REVENGE THE IMPACT OF COLLATERAL DAMAGE ON TALIBAN INSURGENCY by Raja G. Hussain March 2008 Thesis Advisor: Thomas H. Johnson Thesis Co Advisor: Feroz H. Khan Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE BADAL: A Culture of Revenge 5. FUNDING NUMBERS The Impact of Collateral Damage on Taliban Insurgency 6. AUTHOR(S) Raja G. Hussain 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 131 “New Silk Road: Business Cooperation and Prospective of Economic Development” (NSRBCPED 2019) The Analysis of UK and US Migration Policies in Relation to the Middle East Countries Aleksander Eremin Irina Kuprieva The faculty of intercultural communications and The faculty of Linguistics international relations A.S. Griboedov Institute of International Law and Belgorod National Research University Economics Belgorod, Russia The School of Education [email protected] Far Eastern Federal University Moscow, Russia [email protected] Abstract— Of course, the influx of migrants to the countries unskilled ones) to which is so great that it begins to threaten mentioned above comes not only from the Middle East and not not only cultural identity, but also the safety of people who only to the UK and the US, but as part of this study, we are originally lived in these territories due to the emerging social interested particularly in the problem of the interaction of the tension. Arabic-speaking and English-speaking peoples. The article analyzes the current situation in the field of In the article, we will try to analyze this problem using the migration policy in the United States and Great Britain, as well example of the United States of America and Great Britain as as the circumstances that led to this. Analysis data may be used continental leaders in terms of the number of incoming to better understand the situation of immigrants from Arab migrants, and consider their situation with migrants from the countries to countries where the official language is English.