Historic House Museum in 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BETH MALONEY, MS Ed Museum Education Consultant

BETH MALONEY, MS Ed Museum Education Consultant www.bethmaloney.com Providing educational expertise to museums, historic sites and cultural organizations for 15 years with a focus on promoting access to cultural resources and developing engaging programs for visitors of all ages. Services include curriculum and program development, interpretation and visitor experience planning and professional development. INTERPRETATIVE AND STRATEGIC PLANNING Winterthur Museum, Gardens & Library November 2018 - present Partner with staff and consultant team to develop plans for an environmentally, financially and socially sustainable model of collection management. Design and facilitate initial kick off meeting, lead envisioning workshops with staff, support efforts to evaluate and engage new audiences and lay the groundwork for growth in interpretive techniques that increase collections accessibility. Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area January 2015 – present Research educational programming and content at historic sites, museums, and parks within the Heritage Area. Assess the potential strengths and focus to highlight in an online portal serving teachers and student youth travel market. Develop recommendations and educational activities for leveraging connections between Heritage Area sites and Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War PBS documentary and www.crossroadsofwar.org website. Train staff at 10 historic sites throughout the region through grant funded professional development workshop series. National Park Service/Captain John Smith National Historic Trail May – September 2016, September 2017 - present Develop interpretive plan for Susquehanna Heritage, a Visitor Contact Station for the Captain John Smith Historic Trail, including thematic framework, target audience and programming recommendations. Collaborate with larger project team to create a Master plan, including some exhibition elements, for the surrounding region of the lower Susquehanna River, region including historic houses, park lands and recreational areas. -

Press Release

Office of Communications 202.606.8446 | neh.gov PRESS RELEASE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES GRANT AWARDS AND OFFERS, AUGUST 2019 ALASKA (1) $75,000 Anchorage Anchorage Museum Association Outright: $25,000 Match: $50,000 [Media Projects Development] Project Director: Julie Decker Project Title: Alaska Documentary with Ric Burns Project Description: Development of a three-part documentary film on the history of Alaska produced through a partnership between the Anchorage Museum and Steeplechase Films. ARIZONA (2) $156,299 Scottsdale Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Outright: $50,000 [Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections] Project Director: Margo Stipe Project Title: Taliesin West Collections Storage Improvements Plan Project Description: A planning project to address storage improvements for the collections housed at Taliesin West, the winter home and architectural laboratory of Frank Lloyd Wright, in Scottsdale, Arizona. The collection includes thousands of objects designed by Wright, Japanese woodblock prints, Asian screen paintings, textiles, rare books, and archival materials from the Taliesin Associated Architects program. Tucson University of Arizona Outright: $106,299 [Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections] Project Director: Sarah Kortemeier Project Title: Assuring Sustainable Collection Growth with High-Density Mobile Storage Project Description: The purchase and installation of a high-density mobile storage system in the archives room of the University of Arizona Poetry Center. ARKANSAS (2) $410,552 Fayetteville University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Outright: $160,000 [Institutes for School Teachers] Project Director: Sean Connors NEH Grant Awards and Offers, August 2019 Page 2 Project Title: Remaking Monsters and Heroines: Adapting Classic Literature for Contemporary Audiences Project Description: A two-week institute for 30 K-12 educators on Frankenstein, Cinderella, and adaptations of these classic texts. -

ELIZABETH RODINI [email protected]/ 410-303-2682 Erodini.Com

ELIZABETH RODINI [email protected]/ 410-303-2682 erodini.com EDUCATION Ph.D. Art History, University of Chicago (with honors) 1995 M.A. History of Art, University of Michigan 1989 B.A. History and Italian Literature, University of Wisconsin, Madison 1986 Università di Bologna: Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia (1984-85) Awarded a full-tuition Music Clinic Scholarship (viola) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME Andrew Heiskell Arts Director 7/2019 - Advances the work of diverse Rome Prize Fellows in the arts (architecture, design, visual art, historic preservation and conservation, landscape architecture, literature, musical composition), forwards the Academy’s mission and vision for the arts, and encourages programming between and across scholarly and artistic disciplines. Projects to date include: Cinque Mostre: Convergence (exhibition, 2020); Black Artists Retreat Rome, Theaster Gates (2020). In progress at the time of COVID-19: A Century of Music from the American Academy in Rome, three concerts in collaboration with the Auditorium-Parco della Musica; Transitory Landscapes (working title; an exhibition sponsored by the ENEL Foundation). JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY (JHU) Department of the History of Art Fellow by Courtesy, Lecturer 7/2018 - 6/2020 Teaching Professor 7/2012 - 6/2018 Senior Lecturer 7/2006 - 6/2012 Lecturer 7/2004 - 6/2006 Program in Museums and Society (M&S) Director 7/2011 - 6/2018 Associate Director 7/2006 - 6/2011 • Founding director of innovative interdisciplinary academic program in the history, theory, -

RPN Summer13

Summer 2013 Volume Fifty ROLAND PARK NEWS The Roland Water Tower Restoration: A Story of Patience and Persistence by Mary Page Michel At this point, the Roland Water Tower was no The Greater Roland Park Master Plan recommended longer needed. However, it became a convenient many Open Space projects but only three could be turnaround point for the streetcars along Roland chosen as the Roland Park Avenue. This mini-transportation hub Community Foundation’s was used until the technology (RPCF) top projects. The changed once again and the bus restoration of the Roland system became the predominant tower and the creation of mode of transportation. a pocket park at its base Although many people refer to were deemed urgent. By the tower as the Roland PARK July 2009, the tower was Water Tower, the name does not deteriorating so much that include the word “park.” There the city put a chain link was a Roland Park Water Tower, fence around it to protect which supplied water to Roland people from falling debris. Park, constructed about the same The tower, situated on one time in the block just south of of the highest spots in the Petit Louis and the fire station. city, has become an icon It was close to where the Roland and historical landmark Park Country School squash for the neighborhood. One courts are today. This tower was knows one is home at the constructed with exterior steps sight of the tower as you and an observation deck at the exit Interstate 83. What top, but it was later demolished. -

TMS Vol3no1 Schmidt.Pdf

The Enslaved Image: A Contemporary Visualization of Gender & Race JULIANNE SCHMIDT Johns Hopkins University The Museum Scholar www.TheMuseumScholar.org Rogers Publishing Corporation NFP 5558 S. Kimbark Ave, Suite 2, Chicago, IL 60637 www.rogerspublishing.org Cover photo: Restoring the exterior of the Cincinnati Museum Center, Ohio, as part of the two-year renovation. Reopened 2018. Photo by Maria Dehne – Cincinnati Museum Center. ©2019 The Museum Scholar The Museum Scholar is a peer reviewed Open Access Gold journal, permitting free online access to all articles, multi-media material, and scholarly research. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The Enslaved Image: A Contemporary Visualization of Gender & Race JULIANNE SCHMIDT Johns Hopkins University Keywords Interpretation; Kara Walker; Historic House Museums; Slavery; Race; Gender Abstract The reluctance to address difficult history results in its erasure from the dialogue of historic sites. This paper analyzes the use of artwork in historic house museums as a method of confronting the legacy of slavery and racism in the United States. First it discusses the legacy of the African American image in artwork. Next, it considers the structure and impact of The Enslaved Image, an exhibition at Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, that pairs Kara Walker’s silhouette artworks with the social history of enslaved individuals who had lived at the site. Following this analysis is the conclusion on the importance of art in communicating the realities of persisting racial tensions throughout American history. About the Author Julianne M. Schmidt is a rising junior majoring in Art History and International Studies with a minor in Museums and Society at Johns Hopkins University. -

Art & Archaeology Newsletter

d e p a r t m e n t o f Art Archaeology & Newsletter s p r i n g 1 Dear Friends and Colleagues: The past year has had its moments faculty. Next year we will welcome two young Inside scholars, specialists in 19th-century European of tension, mainly about the depart- and Byzantine/medieval art. ment’s financial situation in a period Danny Ćurčić’s magnificent exhibition faculty news “Architecture as Icon” at the Princeton Univer- of an economic baisse. sity Art Museum has become a major magnet Some painful decisions had to be made— 1 for visitors. Drawing on objects from eight graduate student news from staff reduction to cuts in research funds countries, the show offers fascinating examples for faculty—with the goal of preserving fund- of symbolic representations of architecture in ing in vital areas of undergraduate teaching and the context of Byzantine ritual and pilgrimage. 15 graduate student support. Thanks to the careful This successful exhibition is just one result of undergraduate news planning of my predecessor Hal Foster and our the close alliance between the department and department manager Susan Lehre, we emerged the museum. Since the arrival of James Steward from the crisis relatively unscathed. as the museum’s new director last fall, the The transformation of the department department and museum have intensified their seminar study trips over the last few years continues with the collaboration in both teaching and exhibi- retirement of three of our esteemed tions, and James will teach a course on colleagues—Pat Brown, Willy Childs, 18th-century British painting next year. -

A Report on Best Practices in University-Affiliated Historic House

University-affiliated Historic House Museums A report prepared for the 1772 Foundation by Hillary Brady, Steven Lubar and Rebecca Soules July 2014 Overview This report considers the challenges and opportunities universityaffiliated historic house museums face, offering suggestions for new ways to make these museums more useful to the university community. It includes a survey of existing practice, an analysis of recent innovations in the related areas of university art and anthropology museums and of historic house museums more generally, and an overview of other uses for historic houses on university campuses. We thank the 1772 Foundation for its support of this project. Because of the historic connections of the 1772 Foundation with the Liberty Hall Museum, on the campus of Kean University, Union, NJ, we have included several suggestions to begin a conversation about the future of that museum. Our thanks also to the staff at the university historic house museums we spoke with, and to the staff and board members at the Liberty Hall Museum. Many universities have museums. The Association of Academic Museums and Galleries lists hundreds of such museums, mostly museums of art, anthropology, and natural history. A much smaller number have history museums, and a smaller number still have historic house museums. This report provides information on these historic house museums, with an emphasis on the academic and financial relationships of the museum and the university. It is based on phone and email interviews with directors and curators of the historic house museums at eight universities (a total of ten museums), completed between October and December 2013. -

2017 Year in Review

@baltimore_nha Year in Review 8 BALTIMORE NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA BNHA Partnership Programs Engage City Youth With History, Recreation The heritage area is proud to be part of three unique programs that connect the city’s public school students with the city’s vibrant history and natural resources. Baltimore’s Civil Rights Legacy Since 2016, the Baltimore National Heritage Area (BNHA) has partnered with the Maryland Historical Trust and Baltimore Heritage (the city’s preservation advocacy organization) on a project that engages Baltimore City Public School students to explore their local history using the research standards and processes of developing nominations to the National Register of Historic Places. Students investigate Baltimore’s significant role in the Civil Rights Movement and the people and places that reflect this critical time in U.S. and Maryland history. The project is funded in part through a National Park Service Underrepresented Community Grant. The heritage area’s primary role is to help teachers and their students connect to historic sites and resources for researching the Civil Rights Movement. Key partner sites have included Students explore the Gwynns Falls during an Every Kid in a Park excursion. the Maryland Historical Society and the Lillie Carroll Jackson Photo courtesy Carrie Murray Nature Center Civil Rights Museum, which operates under the stewardship of Morgan State University. including the National Park Service. In Maryland, the state Initial planning meetings brought together the heritage area, government has authorized a reciprocal program, allowing the Baltimore Heritage, the city schools’ humanities coordinator, the passes to be accepted at state parks as well. -

Committed to Our Communities – Maryland and Beyond

Johns Hopkins Committed to Our Communities MARYLAND AND BEYOND COVER: The Johns Hopkins Hospital Billings Dome in the context of Baltimore City 80 Broad Street Room 611 appleseed New York, NY 10004 This report was prepared by Appleseed, a New York City-based consulting firm, P: 212.964.9711 founded in 1993, that provides economic research and analysis and economic F: 212.964.2415 development planning services to government, non-profit and corporate clients. www.appleseedinc.com MARYLAND AND BEYOND Committed to our Communities April 2015 4 COMMITTED TO OUR COMMUNITIES Contents 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 17 INTRODUCTION 19 PART ONE / Johns Hopkins in Maryland and beyond – an overview 29 PART TWO / Johns Hopkins as an enterprise 59 PART THREE / Contributing to the development of Maryland’s human capital 71 PART FOUR / Maryland’s leading research institution 83 PART FIVE / Improving health in Maryland and beyond 91 PART SIX / A global enterprise 99 PART SEVEN / Innovation and entrepreneurship at Johns Hopkins 113 PART EIGHT / Investing in and serving our communities 131 PART NINE / The impact of affiliated institutions 137 PART TEN / Johns Hopkins and the future of Maryland’s economy 141 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS MARYLAND AND BEYOND 5 6 COMMITTED TO OUR COMMUNITIES Executive Summary Johns Hopkins as an enterprise • In FY 2014, Johns Hopkins spent nearly $213.6 million on construction and renova- Johns Hopkins is Maryland’s largest private em- tion, including $150.1 million paid to con- ployer, a major purchaser of goods and services, tractors and subcontractors based in Maryland. a sponsor of construction projects and a magnet This investment directly supported 1,104 FTE for students and visitors. -

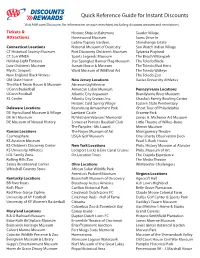

Quick Reference Guide for Instant Discounts

Quick Reference Guide for Instant Discounts Visit AAA.com/Discounts for information on each merchant, including discount amount and restrictions. Tickets & Historic Ships in Baltimore Sauder Village Attractions Homewood Museum Sonic Drive In Ladew Topiary Gardens Stonehenge Estate Connecticut Locations National Museum of Dentistry Sun Watch Indian Village CT Historical Society Museum Port Discovery Children’s Museum Sylvania Playland CT Sun WNBA Sports Legends Museum The Beach Waterpark Holiday Light Fantasia Star Spangled Banner Flag Museum The Toledo Blade Lutz Children’s Museum Surratt House & Museum The Toledo Mud Hens Mystic Seaport Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art The Toledo Walleye New England Black Wolves The Toledo Zoo Old State House New Jersey Locations Xavier University Athletics The Mark Twain House & Museum Absecon Lighthouse UConn Basketball American Labor Museum Pennsylvania Locations UConn Football Atlantic City Aquarium Brandywine River Museum XL Center Atlantic City Cruises, Inc. Chacko’s Family Bowling Center Historic Cold Spring Village Eastern State Penitentiary Delaware Locations Keansburg Amusement Park Ghost Tour of Philadelphia DE Agricultural Museum & Village Lambert Castle Graeme Park DE Art Museum NJ Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial James A. Michener Art Museum DE Museum of Natural History Somerset Patriots Baseball Club Little Theatre of Wilkes-Barre The Funplex - Mt. Laurel Mercer Museum Kansas Locations The Noyes Museum of Art Montgomery Theatre Cosmosphere USGA Golf Museum One Liberty Observation Deck KS Aviation -

Johns HOPKINS Magazine 2013 MCDONOGH SUMMER PROGRAMS

Flu Review p.36 The Arctic, Unfrozen p.12 Punk Prayers and Russian Dissidence p.19 What an outhouse’s history can PRIVY, THEN & NOW teach us about ourselves. p.52 Curios at the Commons p.14 VOLUME 64 NO. 4 WINTER 2012 Music in Terezín p.28 Admission: Impossible? p.80 Forefront: Jazz Talking p.18 johns HOPKINS magazIne 2013 MCDONOGH SUMMER PROGRAMS DON’T LET YOUR CHILD MISS OUT ON A SUMMER OF FUN! Camp Red Feather, Camp Red Eagle, Senior Camp, and Outdoor Adventure Camp all offer the traditional day-camp experience on our beautiful 800-acre campus. They include: L free transportation L free lunch L before- and after-care L multiple-sibling discount To find out about the 70 camps, sports clinics and academic programs that McDonogh offers in the summer, call 410-998-3519, visit www.mcdonogh.org or e-mail [email protected]. L Call now for early bird specials! Volume 64 No. 4 Winter 2012 | 1 Recommended reading from Johns Hopkins Tapping into The Wire Polar Bears Einstein’s Jewish Science The Real Urban Crisis A Complete Guide to Their Physics at the Intersection Peter L. Beilenson, M.D., M.P.H., Biology and Behavior of Politics and Religion and Patrick A. McGuire Text by Andrew E. Derocher Steven Gimbel featuring a conversation with David Simon Photographs by Wayne Lynch “Gimbel is an engaging writer … he takes “Living in Baltimore for most of the ve years that “This magnicent species has got the book it readers on enlightening excursions through I lmed The Wire, I was astounded to see how deserves.”—BBC Wildlife Magazine the nature of Judaism, Hegelian philosophy, closely life mirrors art for too many residents of 978-1-4214-0305-2 $29.96 (reg. -

Tales from the Chew Family Papers: the Charity Castle Story

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS Tales from the Chew Family Papers: The Charity Castle Story WO RECENT DEVELOPMENTS will soon make the rich historical documentation of the Chew Family Papers, The Historical TSociety of Pennsylvania’s largest collection of family papers, avail- able to scholars to an unprecedented extent. One is the transfer of a substantial number of papers from Cliveden, the Chew family country house in the Germantown section of Philadelphia,1 to the Historical Society, which brings the collection together in one research institution for the first time. The second is the Historical Society’s receipt of a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to complete the processing of this extensive and extremely valuable collection. The letters presented below showcase some of the wealth of material that will soon be more accessible to researchers and document just one of the many stories waiting to be uncovered and told. The Chew Family donated its papers to the Historical Society in 1982, and at that time all the known papers were transferred from Cliveden to the society.2 But such was their volume and ubiquity throughout the mansion that by 2000 Cliveden staff had assembled a secondary archive consisting of eighty shelf-feet of additional documents. Fortunately, all of these materials were transferred to HSP in 2006.3 I am deeply indebted to Catherine Rogers Arthur of the Homewood Museum and Mary Clement Jeske of the Charles Carroll of Carrollton Papers, both located in Baltimore, Maryland, for their assistance preparing this article. Both are avid followers of Charity’s saga.