Boko Haram: a Prognosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: OSUAGWU, Linus Chukwunenye. Status: Professor & Former Vice Chancellor. Specialization: Business Admi

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: OSUAGWU, Linus Chukwunenye. Status: Professor & Former Vice Chancellor. Specialization: Business Administration/Marketing . Nationality: Nigerian. State of Origin: Imo State of Nigeria (Ihitte-Uboma LGA). Marital status: Married (with two children: 23 years; and 9 years). Contact address: School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria,Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria; Tel: +2348033036440; +2349033069657 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Skype ID: linus.osuagwu; Twitter: @LinusOsuagwu Website: www.aun.edu.ng SCHOOLS ATTENDED WITH DATES: 1. Comm. Sec. School, Onicha Uboma, Ihitte/Uboma, Imo State, Nigeria (1975 - 1981). 2. Federal University of Technology Owerri, Nigeria, (1982 - 1987). 3. University of Lagos, Nigeria (1988 - 1989; 1990 - 1997). ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: PhD Business Administration/Marketing (with Distinction), University of Lagos, Nigeria, (1998). M.Sc. Business Administration/Marketing, University of Lagos, Nigeria, (1990). B.Sc. Tech., Second Class Upper Division, in Management Technology (Maritime), Federal University of Technology Owerri (FUTO), Nigeria (1987). 1 WORKING EXPERIENCE: 1. Vice Chancellor, Eastern Palm University, Ogboko, Imo State, Nigeria (2017-2018). 2. Professor of Marketing, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola (May 2008-Date). 3. Professor of Marketing & Chair of Institutional Review Boar (IRB), American University of Nigeria Yola (2008-Date). 4. Professor of Marketing & Dean, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola (May 2013-May 2015). 4. Professor of Marketing & Acting Dean, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria (January 2013-May 2013) . 5. Professor of Marketing & Chair of Business Administration, Department of Business Administration, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria (2008-2013). 6. -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

Combined June

TABLE OF CONTENTS Tuesday, June 2, 2020 Geoffrey Burkhart Biography ............................................................................................. 2 Geoffrey Burkhart Testimony .......................................................................................... 3-7 Geoffrey Burkhart Attachment 1 ................................................................................... 8-32 Geoffrey Burkhart Attachment 2 ................................................................................. 33-55 Douglas Wilson Biography ............................................................................................... 56 Douglas Wilson Testimony.......................................................................................... 57-62 Douglas Wilson Attachment 1 ..................................................................................... 63-75 Douglas Wilson Attachment 2 ..................................................................................... 76-78 Douglas Wilson Attachment 3 ..................................................................................... 79-81 Carlos Martinez Biography ............................................................................................... 82 Carlos Martinez Testimony.......................................................................................... 83-87 Carlos Martinez Attachment ...................................................................................... 88-184 Mark Stephens Biography.............................................................................................. -

PASA 2005 Final Report.Pdf

PAN AFRICAN SANCTUARY ALLIANCE 2005 MANAGEMENT WORKSHOP REPORT 4-8 June 2005 Mount Kenya Safari Lodge, Nanyuki, Kenya Hosted by Pan African Sanctuary Alliance / Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary Photos provided by Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary – Sierra Leone (cover), PASA member sanctuaries, and Doug Cress. A contribution of the World Conservation Union, Species Survival Commission, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) and Primate Specialist Group (PSG). © Copyright 2005 by CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Prepared by participants in the PASA 2005 Management Workshop, Mount Kenya, Kenya, 4th – 8th June 2005 W. Mills, D. Cress, & N. Rosen (Editors). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2005. Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report. Additional copies of the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation -

The Concepts of Al-Halal and Al-Haram in the Arab-Muslim Culture: a Translational and Lexicographical Study

The concepts of al-halal and al-haram in the Arab-Muslim culture: a translational and lexicographical study NADER AL JALLAD University of Jordan 1. Introduction This paper1 aims at providing sufficient definitions of the concepts of al-Halal and al-Haram in the Arab-Muslim culture, illustrating how they are treated in some bilingual Arabic-English dictionaries since they often tend to be provided with inaccurate, lacking and sometimes simply incorrect definitions. Moreover, the paper investigates how these concepts are linguistically reflected through proverbs, collocations, frequent expressions, and connota- tions. These concepts are deeply rooted in the Arab-Muslim tradition and history, affecting the Arabs’ way of thinking and acting. Therefore, accurate definitions of these concepts may help understand the Arab-Muslim identity that is vaguely or poorly understood by non-speakers of Arabic. Furthermore, to non-speakers of Arabic, these notions are often misunderstood, inade- quately explained, and inaccurately translated into other languages. 2. Background and Methodology The present paper is in line with the theoretical framework, emphasizing the complex relationship between language and culture, illustrating the importance of investigating linguistic data to understand the Arab-Muslim vision of the world. Linguists like Boas, Sapir and Whorf have extensively studied the multifaceted relationship between language and culture. Other examples are Hoosain (1991), Lucy (1992), Gumperz y Levinson (1996), 1 This article is part of the linguistic-cultural research done by the research group HUM-422 of the Junta de Andalucía and the Research Group of Experimental and Typological Linguistics (HUM0422) of the Junta de Andalucía and the Project of Quality Research of the Junta de Andalucia P06-HUM-02199 Language Design 10 (2008: 77-86) 78 Nader al Jallad Luque Durán (2007, 2006a, 2006b), Pamies (2007, 2008) and Luque Nadal (2007, 2008). -

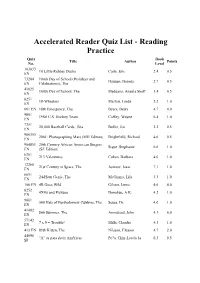

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

ASEBL Journal

January 2019 Volume 14, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of EDITOR (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ▬ ~ GUEST CO-EDITOR ISSUE ON GREAT APE PERSONHOOD Christine Webb, Ph.D. ~ (To Navigate to Articles, Click on Author’s Last Name) EDITORIAL BOARD — Divya Bhatnagar, Ph.D. FROM THE EDITORS, pg. 2 Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. ACADEMIC ESSAY Alison Dell, Ph.D. † Shawn Thompson, “Supporting Ape Rights: Tom Dolack, Ph.D Finding the Right Fit Between Science and the Law.” pg. 3 Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. COMMENTS Joe Keener, Ph.D. † Gary L. Shapiro, pg. 25 † Nicolas Delon, pg. 26 Eric Luttrell, Ph.D. † Elise Huchard, pg. 30 † Zipporah Weisberg, pg. 33 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Carlo Alvaro, pg. 36 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † Peter Woodford, pg. 38 † Dustin Hellberg, pg. 41 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. † Jennifer Vonk, pg. 43 † Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen and Lysanne Snijders, pg. 46 SCIENCE CONSULTANT † Leif Cocks, pg. 48 Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † RESPONSE to Comments by Shawn Thompson, pg. 48 EDITORIAL INTERN Angelica Schell † Contributor Biographies, pg. 54 Although this is an open-access journal where papers and articles are freely disseminated across the internet for personal or academic use, the rights of individual authors as well as those of the journal and its editors are none- theless asserted: no part of the journal can be used for commercial purposes whatsoever without the express written consent of the editor. Cite as: ASEBL Journal ASEBL Journal Copyright©2019 E-ISSN: 1944-401X [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com Member, Council of Editors of Learned Journals ASEBL Journal – Volume 14 Issue 1, January 2019 From the Editors Shawn Thompson is the first to admit that he is not a scientist, and his essay does not pretend to be a scientific paper. -

Christian-Muslim Relations in Contemporary Nigeria

The Precarious Agenda: Christian-Muslim Relations in Contemporary Nigeria Akintunde E. Akinade, High Point University High Point, North Carolina The following lecture was given in Professor Jane Smiths' "Essentials of Christian-Muslim Relations" class in the summer of 2002. The task of mapping out the contemporary challenges to, cleavages within, and contours of Christianity is indeed daunting. Philip Jenkins has recently written a persuasive monograph on the constant flux and fluidity within “the next Christendom.” I agree with him that one of the most persistent challenges for contemporary Christianity is how to respond to the compelling presence of Islam in many parts of the world today. He rightly maintains, “Christian-Muslim conflict may in fact prove one of the closest analogies between the Christian world that was and the one coming into being.”1 This paper examines the contemporary paradigms and models of Christian-Muslim relations in contemporary Nigeria. With a population of over 120 million people, Nigeria has been described by Archbishop Teissier of Algiers as “the greatest Islamo-Christian nation in the world.”2 By this he means that there is no other nation where so many Christians and Muslims live side-by-side. This reality makes Nigeria an important test case for developing patterns of Christian-Muslim relations in Africa. Nigeria provides a rich context for understanding the cultural, social, economic, and political issues that are involved in the Christian-Muslim encounter. Relations between Christianity and Islam over a period of fourteen centuries have ranged from conflict to concord, from polemics to dialogue, from commercial cooperation to open confrontation. -

An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn't

Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t Nasir Abubakar Daniya i Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t. Nasir Abubakar Daniya Student Number: 13052246 A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of Requirements for award of: Professional Doctorate Degree in Policing Security and Community Safety London Metropolitan University Faculty of Social Science and Humanities March 2021 Thesis word count: 104, 482 ii Abstract Since Nigeria’s independence from Britain in 1960, the country has made some progress while also facing some significant socio-economic challenges. Despite being one of the largest producers of oil in the world, in 2018 and 2019, the Brooking Institution and World Poverty Clock respectively ranked Nigeria amongst top three countries with extreme poverty in the World. Muslims from the north and Christians from the south dominate the country; each part has its peculiar problem. There have been series of agitations by the militants from the south to break the country due to unfair treatments by the Nigerian government. They produced multiple violent groups that killed people and destroyed properties and oil facilities. In the North, an insurgent group called Boko Haram emerges in 2009; they advocated for the establishment of an Islamic state that started with warning that, western education is prohibited. Reports say the group caused death of around 100,000 and displaced over 2 million people. As such, Niger Delta Militancy and Boko Haram Insurgency have been major challenges being faced by Nigeria for about a decade. To address such challenges, the Nigerian government introduced separate counterinsurgency interventions called Presidential Amnesty Program (PAP) and Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) in 2009 and 2016 respectively, which are both aimed at curtailing Militancy and Insurgency respectively. -

Interrogating Godfathers

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 19, No.4, 2017) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania INTERROGATING GODFATHERS – ELECTORAL CORRUPTION NEXUS AS A CHALLENGE TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND NATIONAL SECURITY IN FOURTH REPUBLIC NIGERIA 1Preye kuro Inokoba and 2Chibuzor Chile Nwobueze 1Department of Political Science, Niger Delta University, Bayelsa State, Nigeria 2Department Of History & Diplomatic Studies, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt ABSTRACT In all modern democracies, election is not only an instrument for selecting political officeholders but also a vital platform for ensuring government legitimacy, accountability and mobilization of the citizenry for political participation. However, elections in Nigeria since independence have been bedeviled by electoral corruption characterized by such vices as election rigging, snatching of electoral materials, result falsification, political intimidation and assassination before, during and after elections. This situation has often brought unpopular governments to power, with resultant legitimacy crisis, breakdown of law and order and general threat to security. The paper, in explaining the adverse effects of electoral fraud and violence on sustainable development and national security, identified political godfathers as the main orchestrators, masterminds and beneficiaries of electoral corruption in Nigeria. Through the application of the descriptive method of data analysis, the study investigates how godfathers, in a bid to achieve their inordinate political and pecuniary interests, flout all known electoral laws, subvert democratic institutions and governance and as a result threaten national development and security. The paper therefore concludes that, to effectively address the undemocratic practice of electoral corruption, which is a threat to sustainable development and national security, there is need for the strengthening of the legal framework and democratic structures in Nigeria.