Midwest Agriculture Immigration.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum's 24Th Annual

Media only: Marcia Baird Burris (202) 633-4876; (202) 320-1735 (cell) Jan. 15, 2009 Media Web site: http://newsdesk.si.edu; http://anacostia.si.edu The Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum’s 24th Annual Martin Luther King Jr. Program Focuses on Latinos and Civil Rights The Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum presents Baldemar Velásquez, founder and director of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee, AFL-CIO, as the featured speaker for the museum’s 24th Annual Martin Luther King Jr. Program being held Thursday, Jan. 15, at 7 p.m. Velásquez will speak on the topic, “Latinos and Civil Rights: Changing the Face of America” at Baird Auditorium in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. This year’s program is co-sponsored by the Smithsonian Latino Center. The event will include a performance by Chicano guitarist and singer Rudy Arredondo. Admission is free, but seating is limited. To obtain more information or make reservations, e-mail [email protected] or call (202) 633-4875. “Each year we select a speaker or presentation that embodies the philosophy of Dr. King,” said Camille Giraud Akeju, museum director. “Dr. King was empathetic to the plight of migrant workers. A grass-roots organizer like King, Baldemar Velásquez has effectively worked through the system, sometimes one person at a time, and emerged a powerful advocate against injustice.” “The Smithsonian Latino Center is proud to be partnering with the Anacostia Community Museum on this important event which highlights the shared struggles and support between our communities,” said Eduardo Diáz, director of the center. “Baldemar Velásquez embodies the center’s mission to highlight the contributions of Latinos and their positive impact in the United States, particularly its labor history.” Velásquez is a highly respected national and international leader in the farm-labor movement and in the movement for Latino and immigrant rights. -

Like Machines in the Fields: Workers Without Rights in American Agriculture SHIHO FUKADA

Like Machines in the Fields: Workers without Rights in American Agriculture SHIHO FUKADA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Like Machines in the Fields: Workers without Rights in American Agriculture would not have occurred without the contributions of many hands. First of all, Dina Mesbah, a rural development specialist, coordinated the research and wrote a large part of the report. Oxfam America is extremely grateful for her dedication, insights and patience throughout this eight-month process. Bruce Goldstein and James B. Leonard, of the Farmworker Justice Fund., Inc., (www.fwjustice.org) provided original research that served as the basis for the Section IV on injustice in the law. At Oxfam America’s requests, Phil Mattera and Mafruza Khan of the Corporate Research Project of Good Jobs First researched supply-chain dynamics in the fresh tomatoes and pickling cucumber sectors which is treated in Section III. A number of others made key contributions in research and/or writing. These people include: Beth Williamson, Ileana Matamoros, Simon Billenness, and Minor Sinclair. Others read portions of the draft and provided invaluable insights. These people are Greg Asbed, Baldemar Velásquez, Gilbert Apodaca, Bruce Goldstein, Bernadette Orr, Diego Low, Katherine Daniels, Chad Dobson, Judith Gillespie, Amy Shannon, Maria Julia Brunette, Laura Inouye, Larry Ludwig, Brian Payne, Beatriz Maya, Edward Kissam and Mary Sue Smiaroski. A particular word of thanks is due to Minor Sinclair who insists that rights for farmworkers is a core concern for a global development agency such as Oxfam America. And finally we are particularly grateful to three photographers—Andrew Miller, Davida Johns and Shiho Fukada—who graphically portrayed the reality of farmworkers in ways to which our words only aspired. -

Oppression and Farmworker Health in a Global Economy a Call to Action for Liberty, Freedom and Justice

Oppression and Farmworker Health in a Global Economy A call to action for liberty, freedom and justice By Baldemar Velasquez Baldemar Velasquez, human rights activist and founder and Certainly the environmental issues that farmworkers face president of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) are not limited to the exposure to dangerous pesticides. Gen- AFL-CIO, headquartered in Toledo, Ohio, was born in Pharr, erally, the working conditions of farmworkers are a national Texas in 1947. His parents were migrant farmworkers, and he disgrace. It is not only disgraceful, but it is shameful for the began working in the fields at age six, picking berries and to- richest country in the world to continue to ignore and ne- matoes. He formed FLOC in 1967. In 1983, Mr. Velasquez led a glect some of the hardest working people in America. historic 600-mile march of 100 farmworkers from FLOC head- quarters in Toledo to Campbell’s Soup Company headquarters in Camden, New Jersey. Three years later, the migrant work- NAFTA & Immigrant farmworkers ers, growers and Campbell’s announced a three-way pact in Traditional Mexican workers who have migrated from Texas, which the growers agreed to give farmworkers limited medical Florida and other places to the west coast, midwest and the insurance, a paid holiday and a wage increase. It was the first east coast to harvest vegetables, are being joined now by a three-way pact in labor history. huge wave of immigrant workers from Mexico and Central What follows are excerpts of a talk and singing by Mr. Velasquez America who are invading the U.S. -

Dick Wiesenhahn 1974 – 1979

Dick Wiesenhahn 1974–1979 I was probably the last person in Cincinnati who thought he would ever join the farmworker movement, or any cause for that matter. After serving four years in the Coast Guard as a radioman first class and selling golf equipment for the MacGregor Golf Company for 12 years to country-club golf professionals, I was about as conservative as you could get. Everything changed for me in December of 1974 when I was handed a leaflet outside the Kroger store in Hyde Park by two college-age women. The leaflet stated that they were both fasting from all food for 10 days as an act of solidarity with migrant farmworkers in California. The United Farm Workers (UFW) union was on strike and was asking folks to honor its boycotts of table grapes, head lettuce, and Gallo wines in order to pressure growers to negotiate union contracts. Reverend John Waite of the National Farm Worker Ministry (NFWM) was organizing the local UFW boycott effort from a storefront office on Race Street in downtown Cincinnati. He suggested that I read as much as possible so that I would be well informed about the living and working conditions of farmworkers in California and the need for a consumer boycott nationwide. Several weeks later, four of us traveled to Louisville, Kentucky, for a “non-meal meal” sponsored by the UFW. The meal consisted of beans and cornbread, which we were informed farmworkers eat every day. We were joined by UFW supporters from Kentucky and Indiana to hear a presentation from a panel of UFW officials giving us an update on the strikes and boycott and answering questions from the audience. -

September 25, 2002

Ohio & Michigan’s Oldest Latino Newspaper «Tinta con sabor» • Founded in 1989 • Check out our Classifieds! Checa los Anuncios Clasificados! Proudly Serving Our Readers Continuously For Over 13 Years September/septiembre 25, 2002 Spanglish Weekly/Semanal Vol. 32, No. 2 La Prensa is for non-Latinos too! Special Edition: National Latino Awareness Month Surf our web at: www.laprensatoledo.com CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR Remembering (NATIONAL LATINO AWARENESS MONTH ( ( ( ( ( Toledo’s first ON PAGE 12 Latino families: Ohio Lottery Results, 9-21-02 A La Prensa National Game Results Payout Latino Awareness/ Mid-day Pick 3 1-9-1 $906,465 Mid-day Pick 4 3-6-7-9 $ 62,700 Hispanic Heritage Pick 3 2-7-0 $227,839 Month Exclusive Pick 4 4-2-9-7 $148,800 2nd in a series of articles: Buckeye5 16-20-26-30-33 $ 57,357 Super Lotto Plus 3-7-16-26-28-38 $22 Million Kicker 5-8-5-9-2-9 $ 99,280 La Familia Mega Millions[9-20-02]1-2-4-5-46 $23 Million Flores $ By Alan Abrams La Prensa Senior Michigan Lottery Results Correspondent Michigan Millions 17-19-27-40-42-49 “My parents, José Suarez Michigan Roll Down 19-20-23-32-33 Mid-day Daily 3 586 Flores and Carmen Ventura Eve. Daily 3 602 Flores, were the parents of Mid-day Daily 4 8949 seven children who were Eve. Daily 4 2480 raised to adulthood. Only five are living now,” says no tendría obstáculo en $ Judge Joseph Flores. BREVES considerar su participación en “We figure our dad first Cuba considera «un tareas civiles, nunca en una dinosaurio» embargo coalición militar para atacar a came to the U.S. -

Congressional Record—House H3441

April 17, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H3441 They claim that they are not pros- THE FARM LABOR RECRUITMENT ploited is a continental sacrilege. The ecuting drug cases because they are SYSTEM problem with NAFTA and NAFTA- prosecuting folks that illegally enter The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under a style trade agreements is they fail to the United States. But maybe that is previous order of the House, the gentle- take people into account. not true either. These same memos woman from Ohio (Ms. KAPTUR) is rec- NAFTA and NAFTA-style agree- now reveal that in the State of Texas ognized for 5 minutes. ments serve the interests primarily of an illegal coming into the United Ms. KAPTUR. Mr. Speaker, on April the money classes. They reduce risks States has to be captured six times be- 9, 2007, 29-year-old Toledoan, Santiago for Wall Street investors while raising fore they are actually prosecuted Raphael Cruz, was found bound, gagged the risk that workers in our heartland criminally for being in the United and beaten to death in Monterrey, will lose their jobs and health care. States. Mexico, in the office of his employer, They are manna for hedge funds, but a What happens is if they are caught the Toledo-based Farm Labor Orga- threat to the economic security of blue the first six times, they are just taken nizing Committee, or FLOC. collar workers. home. Of course, they come right back Mr. Cruz moved from Toledo, Ohio, to b 1930 to the United States. They are not Mexico 3 months ago to legally arrange being prosecuted. -

Resisting Neoliberal Globalization: Coalition Building Between

RESISTING NEOLIBERAL GLOBALIZATION: COALITION BUILDING BETWEEN ANTI-GLOBALIZATION ACTIVISTS IN NORTHWEST OHIO Kendel A. Kissinger A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2005 Committee: Rekha Mirchandani, Advisor Philip Terrie ii ABSTRACT Rekha Mirchandani, Advisor Few scholars have attempted to document the nature of coalition building within the antiglobalization movement, and this study is an attempt to analyze part of this complex and important social movement. This study is a synopsis of Northwest Ohio’s anti-globalization movement and concentrates on the nature of alliances across movements and the numerous dilemmas they encounter. The major assumption of this project is that neoliberalism dominates the globalization process through the policies and practices of various governance institutions and that the anti-globalization movement arose as a counter-movement in response to neoliberal changes. Based on thirteen interviews conducted within Northwest Ohio’s activist community, this study is a qualitative research project that explores the motivations of labor, peace, farm worker, environmental, and anarchist activists, their concerns about the nature of globalization, and their experiences with cross-movement alliance building. The objective of this study is, first, to provide some historical context on globalization, political and economic thought, coalition building, anti-globalization’s antecedent movements and the broader national and international movement; second, to explain how and why various social movements in Northwest Ohio became part of the anti-globalization movement and identify the problematic issues of cross-movement alliances. The study begins with a review of literature on coalitional movements, anti-globalization activism, and the antecedent movements of Northwest Ohio’s anti-globalization movement. -

North Carolina's Capitalists' Pigs Sharecropping in the New Millennium

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 12-31-1998 Resist Newsletter, Dec. 1998 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Dec. 1998" (1998). Resist Newsletters. 309. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/309 Inside: FLOC Reaches to NC Farm Workers ISSN 0897-2613 • Vol. 7 #10 A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority December 1998 North Carolina's Capitalists' Pigs Sharecropping in the New Millennium STAN GOFF At the end of the day, the integrator appro farmer-peasant class had not disappeared priates the majority of the value produced, but remained strong; so strong, in fact e independent family farm is headed and the contract grower averages between asserted the professor-that it remained o extinction," says Don Webb, a eight and 10 dollars an hour. Thus Mr. more significant than the wage-laboring T:former independent swine farmer Webb's notion that this is a twenty-first class. The current state of agriculture, how from Stantonsburg, North Carolina. "The century form of tenancy. ever, looking at the North Carolina hog in- folks who're still on their land in dustry as an example, makes it this part of North Carolina-the appear that Dr. Hook's critique ones who signed corporate con VD.Allltl& l =• ~ = ~ ~: was premature. tracts-are in denial. They' re Found during the first half of 1998 The application of modem sharecroppers now, and ain't management practices and tech Discharge of hog waste 60 nothin' but pride and hopeless nology to pork production has Discharge into surface water 25 ness keeps 'em in denial about converted farms and slaughter Inadequate freeboard 525 bein' sharecroppers." houses into meat factories. -

Farm Labor Organizing Committee, AFL-CIO

Farm Labor Organizing Committee, AFL-CIO 1221 Broadway Street ♦ Toledo, Ohio 43609 ♦ Phone: 419-243-3456 ♦ Fax: 419-243-5655 ♦ www.floc.com ---FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE--- 04/09/2007 Monterrey, Mexico—It is with pain and sadness that we report the tragic murder of one of our Monterrey, Mexico office staff-members, Santiago Rafael Cruz. We struggle to keep tragedies from occurring in the fields, but it is equally painful to have them occur in our work environment. While we have no official police reports, friends who found the body this morning in the FLOC Monterrey office said that he had been tied-up and beaten to death. FLOC has asked the National AFL-CIO and Congressman Marcy Kaptur’s office to request that our State Department press the Mexican Government to conduct a thorough and speedy investigation to bring the perpetrators to justice. Since our breakthrough agreement in North Carolina in 2004, FLOC has had to battle against anti-union hostility in the South’s “right-to-work” environment. We have put up with constant attacks in both the U.S. and Mexico—including having our staff harassed, our office burglarized and broken into several times and a number of other attempted break-ins. Now the attacks have come to this. FLOC will respond to this attack in a disciplined but forceful manner at the appropriate time. For now, we will focus on Santiago and his family to make sure his body is returned home, and minister to those who loved him. Santiago spent years defending his countrymen’s rights in the U.S. -

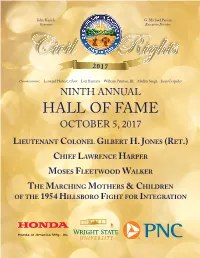

HALL of FAME OCTOBER 5, 2017 Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert H

John Kasich G. Michael Payton Governor Executive Director Civil Rights/ 2017 Commissioners: Leonard Hubert, Chair Lori Barreras William Patmon, III Madhu Singh Juan Cespedes NINTH ANNUAL HALL OF FAME OCTOBER 5, 2017 LIEUTENANT COLONEL GILBERT H. JONES (RET.) CHIEF LAWRENCE HARPER MOSES FLEETWOOD WALKER THE MARCHING MOTHERS & CHILDREN OF THE 1954 HIllSBORO FIGHT FOR INTEGRATION HONDA IT! 11111.MH 11 11 ft Honda of America Mfg., Inc. vVRJGI-IT STATE UNIVERSITY Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame Inductees 2009 2013 William F. Bowen Anison James Colbert Joan B. Campbell Lawrence Eugene “Larry” Doby Robert M. Duncan Sara J. Harper Ruth Gonzalez De Garcia Pastor Robert Lee Harris Bruce Klunder Marjorie B. Parham C.J. Mclin, Jr. Charles O. Ross, Jr. Toni Morrison Alexander M. “Sandy” Spater Fred Shuttlesworth Carl B. Stokes 2014 George Washington Williams Jessie O. Gooding Rev. Mother Louise Shropshire 2010 Joan Evelyn Southgate Avery Friedman Emily T. Spicer Dr. Frank W. Hale, Jr. Judge S. Arthur & Louise Spiegel Dr. Karla Irvine Gloria Steinem William Mcculloch John B. Williams Eric Parks Ohio Freedom Riders: Salvador Ramos Betty Daniels Rosemond Rhonda Rivera David Fankhauser, Ph.D Dr. Ratanjit Sondhe Frances L. Wilson Canty Dr. Marian Spencer Baldemar Velasquez 2015 Nimrod B. Allen 2011 Nirmal K. Sinha Roger Abramson Schuyler Smith & Merri Gaither Smith Theodore M. Berry Louis Stokes Ken Campbell Nathaniel R. Jones 2016 Amos Lynch Judge Jean Murrell Capers Louis D. Sharp Julianna Cochran Rogers V. Anthony Simms-Howell Rev. Leon Troy Richard Weiland 2012 Marion Motley James G. Jackson William Willis Rev. Damon Lynch, Jr. William L. -

Chicano Student Walkout, September 16, 1969, at Kansas City's West

Chicano student walkout, September 16, 1969, at Kansas City’s West High School. This photo appeared in the activist newspaper Vortex. 228 KANSAS HISTORY La Voz de la Gente Chicano Activist Publications in the Kansas City Area, 1968–1989 by Leonard David Ortiz any Chicano student walkouts occurred during the social unrest of the late 1960s in cities such as Los Angeles, San Jose, San Antonio, and Denver. On September 16, 1969, a walkout by Chicano youth took place at West High School in Kansas City, Missouri’s, West Side. MDespite their small numbers, Chicanos and those who identified themselves as Mexican Americans in the Kansas City area were politically active in their communities. Little would be known about the walkout and other Hispanic protests were it not for the local neighborhood and Latino newspapers and newsletters that circulated in Kansas and Missouri during this period.1 The students at West High were supported by the Brown Berets (a Chicano youth activist group agitating for civil rights in the Mexican Ameri- can community), and they made the following demands: the designation of September 16, Mexican Independence Day, as a national holiday in the United States; the creation of solidarity and unity for all Chicanos; and the implementation of Mexican American culture-oriented curriculum changes and bilingual classes. Leonard David Ortiz holds a master’s degree in education from Stanford University and is a doctoral candidate in American history at the University of Kansas. His research interests include Native American history, Chicano history, history of the Ameri- can West, and Latin American history. -

The Campbell Soup Boycott

A Brief History of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) & NFWM’s Support FLOC was founded in 1967 by Baldemar Velasquez, who, with his father, began organizing migrant farm workers in Ohio. The Velasquez family, from Texas, followed the Midwest migrant stream each season. Baldemar organized his first strike at the age of 12, early recognizing, and not accepting, the injustices farm workers faced. Under the leadership of President Baldemar Velasquez, FLOC has set important precedents in labor history: the first farm worker organization to negotiate multi-party collective bargaining agreements; establishment of the Dunlop Commission to act as a “private labor relations board;” the first union to represent H2A guestworkers under a labor agreement. The Campbell Soup Boycott (1978-1986) Fighting to improve conditions for migrant farm workers in the tomato fields of Ohio, FLOC recognized that the power to change things was not in the hands of small and medium sized growers but in the corporate processors who purchased from those growers and dictated the terms of their contracts with them. In 1978, FLOC organized a strike by 2000 workers on farms contracting with Campbell Soup Co. and announced a boycott in 1979. NFWM provided staff to support the Campbell Soup boycott, helping to secure boycott endorsements around the country (including the National Council of Churches), raising awareness in churches and in public demonstrations, often doing human bill-boarding as 7-foot cans of Cream of Exploitation soup. For the historic 560 mile march in 1983 of farm workers and supporters from Toledo to Campbell's headquarters in Camden, NJ, NFWM staff, including Sr Pat Drydyk, Cruz Phillips, Mary Anne Haren, organized food and housing on stops along the way.