Douglas-Fir Beetle Malcolm M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Larch, Which Is the Largest of the American Larches, Occurs Throughout the Forests of West- Ern Montana, Northern Idaho, and East- Ern Washington and Oregon

Forest An American Wood Service Western United States Department of Agriculture Larch FS-243 The spectacular western larch, which is the largest of the American larches, occurs throughout the forests of west- ern Montana, northern Idaho, and east- ern Washington and Oregon. Western larch wood ranks among the strongest of the softwoods. It is especially suited for construction purposes and is exten- sively used in the manufacture of lumber and plywood. The species has also been used for poles. Water-soluble gums, readily extracted from the wood chips, are used in the printing and pharmaceutical industries. F–522053 An American Wood Western Larch (Lark occidentalis Nutt.) David P. Lowery1 Distribution Western larch grows in the upper Co- lumbia River Basin of southeastern British Columbia, northeastern Wash- ington, northwest Montana, and north- ern and west-central Idaho. It also grows on the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and north- central Oregon and in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of southeast Wash- ington and northeast Oregon (fig. 1). Western larch grows best in the cool climates of mountain slopes and valleys on deep porous soils that may be grav- elly, sandy, or loamy in texture. The largest trees grow in western Montana and northern Idaho. Western larch characteristically occu- pies northerly exposures, valley bot- toms, benches, and rolling topography. It occurs at elevations of from 2,000 to 5,500 feet in the northern part of its range and up to 7,000 feet in the south- ern part of its range. The species some- times grows in nearly pure stands, but is most often found in association with other northern Rocky Mountain con- ifers. -

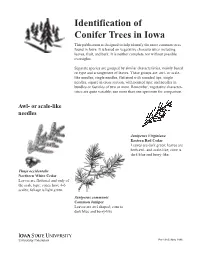

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

Douglasfirdouglasfirfacts About

DouglasFirDouglasFirfacts about Douglas Fir, a distinctive North American tree growing in all states from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, is probably used for more Beams and Stringers as well as Posts and Timber grades include lumber and lumber product purposes than any other individual species Select Structural, Construction, Standard and Utility. Light Framing grown on the American Continent. lumber is divided into Select Structural, Construction, Standard, The total Douglas Fir sawtimber stand in the Western Woods Region is Utility, Economy, 1500f Industrial, and 1200f Industrial grades, estimated at 609 billion board feet. Douglas Fir lumber is used for all giving the user a broad selection from which to choose. purposes to which lumber is normally put - for residential building, light Factory lumber is graded according to the rules for all species, and and heavy construction, woodwork, boxes and crates, industrial usage, separated into Factory Select, No. 1 Shop, No. 2 Shop and No. 3 poles, ties and in the manufacture of specialty products. It is one of the Shop in 5/4 and thicker and into Inch Factory Select and No. 1 and volume woods of the Western Woods Region. No. 2 Shop in 4/4. Distribution Botanical Classification In the Western Douglas Fir is manufactured by a large number of Western Woods Douglas Fir was discovered and classified by botanist David Douglas in Woods Region, Region sawmills and is widely distributed throughout the United 1826. Botanically, it is not a true fir but a species distinct in itself known Douglas Fir trees States and foreign countries. Obtainable in straight car lots, it can as Pseudotsuga taxifolia. -

Current U.S. Forest Data and Maps

CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA AND MAPS Forest age FIA MapMaker CURRENT U.S. Forest ownership TPO Data FOREST DATA Timber harvest AND MAPS Urban influence Forest covertypes Top 10 species Return to FIA Home Return to FIA Home NEXT Productive unreserved forest area CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA (timberland) in the U.S. by region and AND MAPS stand age class, 2002 Return 120 Forests in the 100 South, where timber production West is highest, have 80 s the lowest average age. 60 Northern forests, predominantly Million acreMillion South hardwoods, are 40 of slightly older in average age and 20 Western forests have the largest North concentration of 0 older stands. 1-19 20-39 40-59 60-79 80-99 100- 120- 140- 160- 200- 240- 280- 320- 400+ 119 139 159 199 240 279 319 399 Stand-age Class (years) Return to FIA Home Source: National Report on Forest Resources NEXT CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA Forest ownership AND MAPS Return Eastern forests are predominantly private and western forests are predominantly public. Industrial forests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. Timber harvest by county FOREST DATA AND MAPS Return Timber harvests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. The South is the largest timber producing region in the country accounting for nearly 62% of all U.S. timber harvest. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. -

Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs

INSECTS THAT FEED ON COLORADO TREES AND SHRUBS1 Whitney Cranshaw David Leatherman Boris Kondratieff Bulletin 506A TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFOLIATORS .................................................... 8 Leaf Feeding Caterpillars .............................................. 8 Cecropia Moth ................................................ 8 Polyphemus Moth ............................................. 9 Nevada Buck Moth ............................................. 9 Pandora Moth ............................................... 10 Io Moth .................................................... 10 Fall Webworm ............................................... 11 Tiger Moth ................................................. 12 American Dagger Moth ......................................... 13 Redhumped Caterpillar ......................................... 13 Achemon Sphinx ............................................. 14 Table 1. Common sphinx moths of Colorado .......................... 14 Douglas-fir Tussock Moth ....................................... 15 1. Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University Cooperative Extension etnomologist and associate professor, entomology; David Leatherman, entomologist, Colorado State Forest Service; Boris Kondratieff, associate professor, entomology. 8/93. ©Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 1994. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension office. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, -

Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-Growth Douglas-Fir-Western Hemlock Forest

3589 David M. Braun, Bi Runcheng, David C. Shaw, and Mark VanScoy, University of Washington, Wind River Canopy Crane Research Facility, 1262 Hemlock Rd., Carson, Washington 98610 Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-growth Douglas-fir-Western Hemlock Forest Abstract Folivory of vine maple was documented in an old-growth Douglas-fir-western hemlock forest in southwest Washington. Leaf consumption by lepidopteran larvae was estimated with a sample of 450 tagged leaves visited weekly from 7 May to 11 October, the period from bud break to leaf drop. Lepidopteran taxa were identified by handpicking larvae from additional shrubs and rearing to adult. Weekly folivory peaked in May at 1.2%, after which it was 0.2% to 0.7% through mid October. Cumulative seasonal herbivory was 9.9% of leaf area. The lepidopteran folivore guild consisted of at least 22 taxa. Nearly all individuals were represented by eight taxa in the Geometridae, Tortricidae, and Gelechiidae. Few herbivores from other insect orders were ob- served, suggesting that the folivore guild of vine maple is dominated by these polyphagous lepidopterans. Vine maple folivory was a significant component of stand folivory, comparable to — 66% of the folivory of the three main overstory conifers. Because vine maple is a regionally widespread, often dominant understory shrub, it may be a significant influence on forest lepidopteran communities and leaf-based food webs. Introduction tract to defoliator outbreaks, less is known about endemic populations of defoliators and low-level Herbivory in forested ecosystems consists of the folivory. consumption of foliage, phloem, sap, and live woody tissue by animals. -

Panel Trap Info Sheet P1.Cdr

INSECT MONITORING SYSTEMS !!!! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! !!!! ! !!.$2/0)#!, ! 6 %"6+*6 6-6%6 .16.()"6(+6$)%.)+%6 )"4.-6 +$4-6 0+-.-6 &6(.+6)+-.6 )")*.+6'6 4$%)*.+6 6+61+46+(/-.6 /%+6+!)+(/-6#6)%.)%-6 46+6" .3.6-46.(6,+56 2.+ %62.+*+()6%6-46 .(6%-.""6 6---$"6 +*"56-.)+66%6/-6"--6 -.(+6-*6.%6 /%%#6.+*-6 $$ $ #$$ $ $$ "$$$"!$ # $ $$ $ /-> 65>+>;3+95> /">7#5> )>)$>1->)> )/)> :))%>0.> /5>< 8!)>7>5(>5- 5>,#%+<>=>8>5(>#&'4>0> *+7>5 )!!)7%= 0)8 >) >. > )%>2.> 2 2 02. ,.2$$!( 2 2 2 2 0 /0 12 2 '/"+)2 ()/2 +-*%2 +-)&2 %2+''-2 -!2 -"2 +!#2)2 (%2-"2 -"2 -"2 Alpha Scents, Inc., 1089 Willamette Falls Drive, West Linn, OR 97068 Tel. 503-342-8611 • Fax. 314-271-7297 • [email protected] www.alphascents.com beetles, longhorn beetles, wood wasps, and other timber infesting pests. 25 20 Panel Trap is commercially available for ts Comparative Trapping of Forest Coleoptera, ns ec f i 15 # o PT and Multi-Funnel Trap, Cranberry Lake, NY, 10 5 0 Three types of traps were tested: PT treated with Rain-X , PT untreated (PT), and Multi-Funnel Trap (Phero-Tech, Inc.). The traps were baited with three lure prototypes: (1) standard lure (alpha-pinene (ap), ipdienol (id), PT #1-R 12 Funnel #1 ipsenol (ie), (2) turpentine lure (turpentine, id, ie), and (3) ethanol lure (ethanol, ap, id, ie). 14 ec t s 12 ns 10 of i PT and Multi-Funnel # Summer 2002 8 Comparative Trapping of Forest Coleoptera, 6 4 2 0 effective toolThe for Panel monitoring Trap is Cerambycids,an as well as Scolytids, Buprestids, and other forest Coleoptera. -

Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite After Infection with the Hymenoscyphus Fraxineus and Phytophthora Species

Article Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species Nenad Keˇca 1,*, Milosz Tkaczyk 2, Anna Z˙ ółciak 2, Marcin Stocki 3, Hazem M. Kalaji 4 ID , Justyna A. Nowakowska 5 and Tomasz Oszako 2 1 Faculty of Forestry, University of Belgrade, Kneza Višeslava 1, 11030 Belgrade, Serbia 2 Forest Research Institute, Department of Forest Protection, S˛ekocinStary, ul. Braci Le´snej 3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (A.Z.);˙ [email protected] (T.O.) 3 Faculty of Forestry, Białystok University of Technology, ul. Piłsudskiego 1A, 17-200 Hajnówka, Poland; [email protected] 4 Institute of Technology and Life Sciences (ITP), Falenty, Al. Hrabska 3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland; [email protected] 5 Faculty of Biology and Environmental Sciences, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw, Wóycickiego 1/3 Street, 01-938 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +381-63-580-499 Received: 6 June 2018; Accepted: 10 July 2018; Published: 24 July 2018 Abstract: The European Fraxinus species are threatened by the alien invasive pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, which was introduced into Poland in the 1990s and has spread throughout the European continent, causing a large-scale decline of ash. There are no effective treatments to protect ash trees against ash dieback, which is caused by this pathogen, showing high variations in susceptibility at the individual level. Earlier studies have shown that the application of phosphites could improve the health of treated seedlings after artificial inoculation with H. -

Aircraft Wood Information

TL 1.14 Issue 2 1 Jan 2008 AIRCRAFT WOOD INFORMATION Wood is used throughout the world for a wide variety of purposes. It is stronger for its weight than any other material excepting certain alloy steels. Timber is readily worked by hand, using simple tools and is, therefore, far cheaper to use than metal. To appreciate the use of timber in aircraft construction, it is necessary to learn something about the growth and structure of wood. There are two types" of tree—the conifer or evergreen, and the deciduous. A coniferous tree is distinguished by its needle-like leaves. Its seeds are formed in the familiar cone-shaped pod. From a conifer, 'softwood' is obtained. A deciduous tree has broad, flat leaves which it sheds in the autumn. Its seeds are enclosed in ordinary cases as for example, the oak, birch and walnut. Timber from deciduous trees is said to be 'hardwood'. It can be seen, therefore, that the term 'softwood' and 'hardwood' apply to the family or type of tree and do not necessarily indicate the density of the wood. That is why balsa, the lightest and most fragile of woods, is classed as a hardwood. Both hardwood and softwood trees are said to be 'exogenous'. An exogenous tree is one whose growth progresses outwards from the core or heart by the development of additional 'rings' or layers of wood. Certain trees are exceptions to this rule, such as bamboo and palm. This wood is unsuitable for aircraft construction. Exogenous trees grow for only part of the year. -

Landowner's Guide to Restoring and Managing Oregon White Oak Habitats

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The landowner stories throughout the Guide would not have been possible without help from Lynda Boyer, Warren and Laurie Halsey, Mark Krautmann, Barry Schreiber, and Karen Thelen. The authors also wish to thank Florence Caplow and Chris Chappell of the Washington Natural Heritage Program and Anita Gorham of the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) for helping us be�er understand Oregon white oak plant community associations. John Christy of the Oregon Natural Heritage program provided data for mapping pre-se�lement vegetation of the Willame�e Valley. Karen Bahus provided invaluable technical editing and layout services during the preparation of the Guide. Finally, we offer our appreciation to the following members of the Landowner’s Guide Steering Commi�ee: Hugh Snook, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) - Commi�ee Leader, Bob Altman The American Bird Conservancy (ABC), Eric Devlin, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Connie Harrington, U.S.D.A. Forest Service (USFS), Jane Kertis (USFS), Brad Kno�s, Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF), Rachel Maggi, Natural Resource & Conservation Service (NRCS), Brad Withrow-Robinson, Oregon State University Extension Service (OSU), and Nancy Wogen, BLM. These Commi�ee members reviewed earlier dra�s of our work and offered comments that led to significant improvements to the final publication. All photos were taken by the authors unless otherwise indicated. Landowner’s Guide to Restoring and Managing Oregon White Oak Habitats Less than 1% of oak-dominated habitats are protected in parks or reserves. Private landowners hold the key to maintaining this important natural legacy. Landowner’s Guide to Restoring and Managing Oregon White Oak Habitats GLOSSARY OF TERMS GLOSSARY OF TERMS Throughout this Landowner’s Guide, we have highlighted many terms in bold type to indicate that the term is defined in the glossary below. -

Vegetation Descriptions NORTH COAST and MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE

Vegetation Descriptions NORTH COAST AND MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE CALVEG ZONE 1 December 11, 2008 Note: There are three Sections in this zone: Northern California Coast (“Coast”), Northern California Coast Ranges (“Ranges”) and Klamath Mountains (“Mountains”), each with several to many subsections CONIFER FOREST / WOODLAND DF PACIFIC DOUGLAS-FIR ALLIANCE Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) is the dominant overstory conifer over a large area in the Mountains, Coast, and Ranges Sections. This alliance has been mapped at various densities in most subsections of this zone at elevations usually below 5600 feet (1708 m). Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) is a common conifer associate in some areas. Tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. densiflorus) is the most common hardwood associate on mesic sites towards the west. Along western edges of the Mountains Section, a scattered overstory of Douglas-fir often exists over a continuous Tanoak understory with occasional Madrones (Arbutus menziesii). When Douglas-fir develops a closed-crown overstory, Tanoak may occur in its shrub form (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides). Canyon Live Oak (Quercus chrysolepis) becomes an important hardwood associate on steeper or drier slopes and those underlain by shallow soils. Black Oak (Q. kelloggii) may often associate with this conifer but usually is not abundant. In addition, any of the following tree species may be sparsely present in Douglas-fir stands: Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Ponderosa Pine (Ps ponderosa), Incense Cedar (Calocedrus decurrens), White Fir (Abies concolor), Oregon White Oak (Q garryana), Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum), California Bay (Umbellifera californica), and Tree Chinquapin (Chrysolepis chrysophylla). The shrub understory may also be quite diverse, including Huckleberry Oak (Q.