Thesis a Socio-Spatial Rhetorical Analysis of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me Jane Tour Playbill-Final

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN, Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President Kennedy Center Theater for Young Audiences on Tour presents A Kennedy Center Commission Based on the book Me…Jane by Patrick McDonnell Adapted and Written by Patrick McDonnell, Andy Mitton, and Aaron Posner Music and Lyrics by Andy Mitton Co-Arranged by William Yanesh Choreographed by Christopher D’Amboise Music Direction by William Yanesh Directed by Aaron Posner With Shinah Brashears, Liz Filios, Phoebe Gonzalez, Harrison Smith, and Michael Mainwaring Scenic Designer Lighting Designer Costume Designer Projection Designer Paige Hathaway Andrew Cissna Helen Q Huang Olivia Sebesky Sound Designer Properties Artisan Dramaturg Casting Director Justin Schmitz Kasey Hendricks Erin Weaver Michelle Kozlak Executive Producer General Manager Executive Producer Mario Rossero Harry Poster David Kilpatrick Bank of America is the Presenting Sponsor of Performances for Young Audiences. Additional support for Performances for Young Audiences is provided by the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; Anne and Chris Reyes; and the U.S. Department of Education. Funding for Access and Accommodation Programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. Major support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by David M. Rubenstein through the Rubenstein Arts Access Program. The contents of this document do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. " Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. -

The Bankruptcy of Detroit: What Role Did Race Play?

The Bankruptcy of Detroit: What Role did Race Play? Reynolds Farley* University of Michigan at Michigan Perhaps no city in the United States has a longer and more vibrant history of racial conflict than Detroit. It is the only city where federal troops have been dispatched to the streets four times to put down racial bloodshed. By the 1990s, Detroit was the quintessential “Chocolate City-Vanilla Suburbs” metropolis. In 2013, Detroit be- came the largest city to enter bankruptcy. It is an oversimplification and inaccurate to argue that racial conflict and segregation caused the bankruptcy of Detroit. But racial issues were deeply intertwined with fundamental population shifts and em- ployment changes that together diminished the tax base of the city. Consideration is also given to the role continuing racial disparity will play in the future of Detroit after bankruptcy. INTRODUCTION The city of Detroit ran out of funds to pay its bills in early 2013. Emergency Man- ager Kevyn Orr, with the approval of Michigan Governor Snyder, sought and received bankruptcy protection from the federal court and Detroit became the largest city to enter bankruptcy. This paper explores the role that racial conflict played in the fiscal collapse of what was the nation’s fourth largest city. In June 1967 racial violence in Newark led to 26 deaths and, the next month, rioting in Detroit killed 43. President Johnson appointed Illinois Governor Kerner to chair a com- mission to explain the causes of urban racial violence. That Commission emphasized the grievances of blacks in big cities—segregated housing, discrimination in employment, poor schools, and frequent police violence including the questionable shooting of nu- merous African American men. -

Michigan Strategic Fund

MICHIGAN STRATEGIC FUND MEMORANDUM DATE: March 12, 2021 TO: The Honorable Gretchen Whitmer, Governor of Michigan Members of the Michigan Legislature FROM: Mark Burton, President, Michigan Strategic Fund SUBJECT: FY 2020 MSF/MEDC Annual Report The Michigan Strategic Fund (MSF) is required to submit an annual report to the Governor and the Michigan Legislature summarizing activities and program spending for the previous fiscal year. This requirement is contained within the Michigan Strategic Fund Act (Public Act 270 of 1984) and budget boilerplate. Attached you will find the annual report for the MSF and the Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC) as required in by Section 1004 of Public Act 166 of 2020 as well as the consolidated MSF Act reporting requirements found in Section 125.2009 of the MSF Act. Additionally, you will find an executive summary at the forefront of the report that provides a year-in-review snapshot of activities, including COVID-19 relief programs to support Michigan businesses and communities. To further consolidate legislative reporting, the attachment includes the following budget boilerplate reports: • Michigan Business Development Program and Michigan Community Revitalization Program amendments (Section 1006) • Corporate budget, revenue, expenditures/activities and state vs. corporate FTEs (Section 1007) • Jobs for Michigan Investment Fund (Section 1010) • Michigan Film incentives status (Section 1032) • Michigan Film & Digital Media Office activities ( Section 1033) • Business incubators and accelerators annual report (Section 1034) The following programs are not included in the FY 2020 report: • The Community College Skilled Trades Equipment Program was created in 2015 to provide funding to community colleges to purchase equipment required for educational programs in high-wage, high-skill, and high-demand occupations. -

Ghosts, Devils, and the Undead City

SACXXX10.1177/1206331215596486Space and CultureDraus and Roddy 596486research-article2015 Article Space and Culture 1 –13 Ghosts, Devils, and the Undead © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: City: Detroit and the Narrative sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1206331215596486 of Monstrosity sac.sagepub.com Paul Draus1 and Juliette Roddy1 Abstract As researchers working in Detroit, we have become sensitized to the rhetoric often deployed to describe the city, especially the vocabulary of monstrosity. While providing powerful images of Detroit’s problems, insidious monster narratives also obscure genuine understanding of the city. In this article, we first discuss the city of Detroit itself, describing its place in the American and global social imaginary as a product of its particular history. Second, we consider the concept of monstrosity, particularly as it applies to urban environments. Following this, we relate several prevalent or popular categories of monster to descriptions of Detroit, considering what each one reveals and implies about the state of the city, its landscape and its people. Finally, we discuss how narratives of monstrosity may be engaged and utilized to serve alternative ends. Keywords Detroit, monstrosity, drugs, social and spatial imaginary Introduction The city of Detroit has recently received international attention due to its severe population loss, physical ruins, and financial bankruptcy (Draus & Roddy, 2014). Detroit’s decline is often por- trayed as more than a relative economic or demographic trajectory, but as something fated or destined, somehow linked to its essential character. Journalist Frank Owen, for example, called it “a throwaway city for a throwaway society, the place where the American Dream came to die,” in a story tellingly titled “Detroit, Death City” (2004, p. -

Curriculum Vitae for Ashley Lucas, Ph

Curriculum Vitae for Ashley Lucas Associate Professor of Theatre & Drama and the Residential College University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Education 2006 University of California, Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies and Drama and Theatre San Diego (UCSD) Title of Dissertation: “Performing the (Un)Imagined Nation: The Emergence of Ethnographic Theatre in the Late Twentieth Century” Advisors: Dr. Ana Celia Zentella (Ethnic Studies) Dr. Jorge Huerta (Drama and Theatre) 2003 UCSD M.A. in Ethnic Studies Title of Master’s Thesis: “The Politics of the Chicana/o Body on Stage” 2001 Yale University B.A. in English and Theatre Studies with academic distinction in both majors Professional Experience Positions Held 2013—present—Associate Professor of Theatre & Drama, the Residential College, the Penny Stamps School of Art and Design, and the Department of English Language and Literature at UM 2013-2019—Director of the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP) at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (UM) 2008-2012—Assistant Professor of Dramatic Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) 2006-2008—Carolina Postdoctoral Fellow for Faculty Diversity at UNC 2005-2006—Associate-In Professor, Research Assistant, and Doctoral Student at UCSD 2001-2005—Teaching Assistant, Research Assistant, and Doctoral Student at UCSD Academic Conferences February 12, 2020—presented on a panel entitled “Carceral Imaginaries: A Panel on Arts, Race, and Incarceration” at Stanford University in Palo Alto, CA September 16, 2019—co-presented with Vicente Concilio, giving a paper -

ALL BUSINESSES ARE NOT ALIKE Let Us Customize a Communications Solution That’S the Right Fit for You

20120924-NEWS--0018-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 9/20/2012 4:02 PM Page 1 Page 18 CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS September 24, 2012 CRAIN'S LIST: LARGEST ARCHITECTURAL FIRMS Ranked by 2011 revenue Number of registered $ value Company Revenue architects of projects Address ($000,000) local/ ($000,000) Rank Phone; website Top local executive(s) 2011/2010 national 2011/2010 Notable projects Detroit area SmithGroup Inc. (SmithGroupJJR) Jeffrey Hausman $177.1 42 $2,950.0 Comerica Park, Detroit Institute of Arts renovation and expansion, Detroit Medical Center Sinai 500 Griswold St., Suite 1700, Detroit 48226 Detroit office director $179.7 227 $3,000.0 Grace Hospital EDICU and Radiology expansion, Detroit Metropolitan Airport McNamara Terminal, (313) 983-3600; www.smithgroupjjr.com and Carl Roehling Ford Field, Grace Lake Corporate Center, Guardian Building Wayne County Corporate office 1. president and CEO relocation, Henry Ford Health System Innovation Institute, Karmanos Cancer Institute Cancer Research Center and Walt Breast Center, Oakland University Human Health Building, United Way for Southeastern Michigan headquarters relocation Ghafari Inc. Yousif Ghafari 123.0 18 1,500.0 Various projects for Ford, General Motors, College for Creative Studies, Wayne State University, 2. 17101 Michigan Ave., Dearborn 48126 chairman 87.5 37 1,000.0 Schoolcraft College, Cranbrook Educational Community, U.S. General Services Administration (313) 441-3000; www.ghafari.com URS Corp. Ronald Henry 38.6 NA NA NA 3. 27777 Franklin Road, Suite 2000, Southfield vice president and 45.2 NA 650.0 48034 managing principal (248) 204-5900; www.urscorp.com Harley Ellis Devereaux Corp. Michael Cooper 34.2 28 500.0 Detroit Medical Center Cardiovascular Institute, Crittenton Hospital Medical Center, Wayne State 4. -

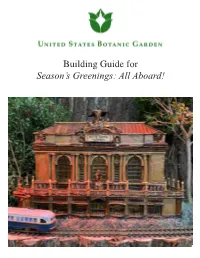

Train Station Models Building Guide 2018

Building Guide for Season’s Greenings: All Aboard! 1 Index of buildings and dioramas Biltmore Depot North Carolina Page 3 Metro-North Cannondale Station Connecticut Page 4 Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal New Jersey Page 5 Chattanooga Train Shed Tennessee Page 6 Cincinnati Union Terminal Ohio Page 7 Citrus Groves Florida Page 8 Dino Depot -- Page 9 East Glacier Park Station Montana Page 10 Ellicott City Station Maryland Page 11 Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad Station Pennsylvania Page 12 Grain Elevator Minnesota Page 13 Grain Fields Kansas Page 14 Grand Canyon Depot Arizona Page 15 Grand Central Terminal New York Page 16 Kirkwood Missouri Pacific Depot Missouri Page 17 Lahaina Station Hawaii Page 18 Los Angeles Union Station California Page 19 Michigan Central Station Michigan Page 20 North Bennington Depot Vermont Page 21 North Pole Village -- Page 22 Peanut Farms Alabama Page 23 Pennsylvania Station (interior) New York Page 24 Pikes Peak Cog Railway Colorado Page 25 Point of Rocks Station Maryland Page 26 Salt Lake City Union Pacific Depot Utah Page 27 Santa Fe Depot California Page 28 Santa Fe Depot Oklahoma Page 29 Union Station Washington Page 30 Union Station D.C. Page 31 Viaduct Hotel Maryland Page 32 Vicksburg Railroad Barge Mississippi Page 33 2 Biltmore Depot Asheville, North Carolina built 1896 Building Materials Roof: pine bark Facade: bark Door: birch bark, willow, saltcedar Windows: willow, saltcedar Corbels: hollowed log Porch tread: cedar Trim: ash bark, willow, eucalyptus, woody pear fruit, bamboo, reed, hickory nut Lettering: grapevine Chimneys: jequitiba fruit, Kielmeyera fruit, Schima fruit, acorn cap credit: Village Wayside Bar & Grille Wayside Village credit: Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, one of the premier architects in American history, the Biltmore Depot was commissioned by George Washington Vanderbilt III. -

Detroit Pistons Game Notes | @Pistons PR

Date Opponent W/L Score Dec. 23 at Minnesota L 101-111 Dec. 26 vs. Cleveland L 119-128(2OT) Dec. 28 at Atlanta L 120-128 Dec. 29 vs. Golden State L 106-116 Jan. 1 vs. Boston W 96 -93 Jan. 3 vs.\\ Boston L 120-122 GAME NOTES Jan. 4 at Milwaukee L 115-125 Jan. 6 at Milwaukee L 115-130 DETROIT PISTONS 2020-21 SEASON GAME NOTES Jan. 8 vs. Phoenix W 110-105(OT) Jan. 10 vs. Utah L 86 -96 Jan. 13 vs. Milwaukee L 101-110 REGULAR SEASON RECORD: 20-52 Jan. 16 at Miami W 120-100 Jan. 18 at Miami L 107-113 Jan. 20 at Atlanta L 115-123(OT) POSTSEASON: DID NOT QUALIFY Jan. 22 vs. Houston L 102-103 Jan. 23 vs. Philadelphia L 110-1 14 LAST GAME STARTERS Jan. 25 vs. Philadelphia W 119- 104 Jan. 27 at Cleveland L 107-122 POS. PLAYERS 2020-21 REGULAR SEASON AVERAGES Jan. 28 vs. L.A. Lakers W 107-92 11.5 Pts 5.2 Rebs 1.9 Asts 0.8 Stls 23.4 Min Jan. 30 at Golden State L 91-118 Feb. 2 at Utah L 105-117 #6 Hamidou Diallo LAST GAME: 15 points, five rebounds, two assists in 30 minutes vs. Feb. 5 at Phoenix L 92-109 F Ht: 6 -5 Wt: 202 Averages: MIA (5/16)…31 games with 10+ points on year. Feb. 6 at L.A. Lakers L 129-135 (2OT) Kentucky NOTE: Scored 10+ pts in 31 games, 20+ pts in four games this season, Feb. -

Detroit Junior College 1923 Yearbook

,---------SPINDlER-SCHOlZ~ ----------, 1564 WOODWARD AVE. Young Men There IS a great difference 111 clothes In selecting a SPINDLER-SCHOLZ suit especially the type worn by college men. you have that confident feeling of looking your best. Our shop IS the only one 111 Detroit Highest quality most moderately priced are catering exclusively to YOUNG MEN. the important factors that capture the confi dence of our customers. Suits Top Coats You will always feel right In a SPINDLER-SCHOLZ suit. Gladwin Bldg . Neckwear Second floor Oxford Shirts (OpPosite David Whitney Bldg.) Olle ART CENTER CONFECTIONERY SODAS WELCOME CANDIES AS YOU PASS BY JAYCIKS and JA YCEETAS FRUrrS GIVE US A TRY DRINRS Next door to 13 Warren Avenue CHRISTESON AND MARINOS Shoe Shine Parlor PI-lONE NORTHWAY 5865 EVERY JAYCIK KNOWS D. R. JARRATT & CO. AUTOMOBILE GLASS "DAD'S KENNEL" 96 WARREN AVENUE WEST HOT DOGS CIGARETTES Near Cass . , DRINKS WIND D EFLECTO RS WINDSHIELD CANDIES SUN AND RAIN VISORS HEADLIGHT AND WINDSHIELD CLEANERS BODY GLASS W e R eplace Glass In Any Make Car While You Wait I 06 WARREN AV E. NEXT COOR TO STUDENT CLUB Two .....~ \ I· Famous Shoes for Men. We're proud to offer you Bostonian Shoes and you'll be proud to wear them, for BOSTONIANS are made from the finest leathers on lasts . for every foot. Their nicety of Finish and Quality workmanship spell satisfaction to every wearer. Their price is as pleasing as their fine service. THE E. & R. SHOE COMPANY 124 Michigan Avenue 614 Woodward Avenue Three Choosing a Business By Arthur G. -

The Moran Family

The Moran Family Copyright 1949 by Alved of Detroit, Incorporated ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published by Alved of Detroit, Incorporated Manufactured in The United States of America THE FAMILY 200 Years in Detroit By J. BELL MORAN ALVED OF DETROIT, INCORPORATED 1949 THE AUTHOR -from a painting by Lawrence Powers Affectionate!y dedicated to my children Publisher's Note FoRMAL, RATHER than private, publication of this book is due to the insistence of Dr. Milo M. Quaife and ourselves. We felt it should be given wider distribution than was the author's intention when the project was begun. Mr. Moran wrote the book for his children and their children, as he so charmingly states in his Introduction. He refused to believe with us, that the mass of new material concerning Detroit's past captured ·into his narrative made the book an important addition to the Americana of Detroit and Michigan. We argued, too, that his boy"s,eye view of Detroit in transition from a City of Homes, in his eighteen--eighties, into Industry's Metropolis when the century turned is the kind of source record from which future historians will gather their information. ""And, equally important, it is splendid reading for today,.,., we said. ""But, I"m a novice at writing," quoth J. Bell Moran. "Thank the Angels for that, if that" s what you are," we murmured right back at him. That we won our way is evident. You have the book before you. After reading it, you will realize how generously the author has shared his Moran Family with you. -

Weekly Detective Story Magazine on in THEATRE ORGAN to Realize

by Lloyd E. Klos One of the nicest personalities in her own ways of handling me. plicated mystery novels whose web the world of the theatre organ is John "My first school experience was work plots fascinated me. Later, I T. Muri. The author has known Mr. unhappy. Bewildered and bashful, I sat moved on to better authors, and now I Muri for several years, having heard under a kindergarten table for some am a fan of Lord Monboddo of Scot him perform four times. Each perfor time before I was encouraged to come land and James Joyce." mance was a testimony to the man's out and mix with the other children. I It should be emphasized that Mr. capabilities as an organist, and as an was always afraid of teachers, particu Muri's reading proclivities stood him in artist in the accompaniment of silent larly one shop teacher who kept a good stead for the years ahead. One need only to read one of his columns films. 3-inch leather strap handy for disci "I was born on October 4, 1906 in plinary purposes. in THEATRE ORGAN to realize how Hammond, Indiana in a fairly large but "Outside of the usual childish fears, reading helped him gain an extensive modest home, situated 35 feet from school life was relatively peaceful. I vocabulary, coupled with excellent the Michigan Central Railroad tracks. passed my classes, but never distin grammatical construction. Constant (Thus Mr. Muri is one of the many guished myself. I found great content reading of good material will do this. -

ASTI Projects in Detroit

Projects in Detroit Highland Park Ford Plant Whittier Hotel Nancy Brown Peace Carillon McGregor Public Library Michigan Central Station Metropolitan United 2014 NAIP Imagery (USDA, Service Methodist Church Center Agencies) ASTI Environmental has provided environmental Highland Park Ford Plant consulting and engineering to the Great Lakes Region since 1985. Conducted Phase I and BEA on Our staff of highly qualified environmental professionals specialize this former Model T factory. in a variety of environmental services including wetland and Owner plans to restore the buildings and create an aquatic resources, threatened and endangered species, natural interpretive center for the public. resource planning and restoration, Brownfields, environmental concerns inventory, Phase I/II ESA, BEA, UST removal, noise and air, compliance, asbestos, lead, Nancy Brown Peace Carillon other hazardous materials Inspected building for lead based surveys, site restoration, paint, asbestos, and other redevelopment incentives, and hazardous substances before restoration work began. due diligence. Metropolitan United Methodist Church Whittier Hotel Phase I completed for the Proposed interior renovations former Whittier apartment hotel. required sampling for asbestos Photo: Andrew Jameson at en.wikipedia in the plaster. Photo: metroumc.org Former Detroit Fire Department Headquarters Michigan Central Station Environmental due diligence and incentives Performed asbestos and LBP completed for acquisition and transformation of inspections prior to filming for building into a boutique hotel. scenes in the Transformers movies. Photo: Andrew Jameson at en.wikipedia 3800 Woodward Conducted the environmental due diligence and secured over $12 million in Brownfield incentives for the redevelopment of an obsolete office building and adjacent mixed use building. All existing structures will be demolished, and a state of the art medical office and retail development with a parking tower will be constructed.