Solar Energy Policy Setting and Applications to Cotton Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZCWP02-19 Renewable Energy Projects on the Indigenous Estate: Identifying Risks and Opportunities of Utility-Scale and Dispersed Models

Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia-Pacific Grand Challenge ZCEAP Working Papers ZCWP02-19 Renewable energy projects on the indigenous estate: identifying risks and opportunities of utility-scale and dispersed models. Kathryn Thorburn, Lily O’Neil and Janet Hunt Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University April 2019 Executive Summary This paper considers the opportunities and risks of renewable energy developments for Aboriginal communities in Australia’s Pilbara and Kimberley regions. These regions in the North West of Australia have very high rates of Indigenous land tenure, as well as being very attractive for both solar and wind power generation, particularly as developing technology makes it feasible to transport power over large distances. They are also areas remote from Australia’s electricity networks and are therefore often reliant on expensive methods of non-renewable electricity generation, including diesel. We consider renewable energy development for these regions at two different scales. This is because research indicates that different size developments can present different opportunities and risks to Aboriginal communities. These scales are utility (between 30 – 600MW) which, at the time of writing, are predominately intended to generate energy for export or industrial use, and via smaller, dispersed models (distributed generation and microgrids under 30 MW) which are currently more likely to be built to supply energy locally. Globally, renewable energy developments have seen a trend towards some amount of community ownership for a variety of reasons including: consumer desire to play a more active role in the generation of energy; social licence to operate considerations in relation to developments usually sited close to high population areas; and governments encouraging or mandating some level of community ownership because of a combination of reasons. -

2021 Full-Year Result

12 August 2021 Results Highlights and Business Update Financial Overview 1 Graeme Hunt, Managing Director and Chief 4 Damien Nicks, Chief Financial Officer Executive Officer Customer Markets Outlook 2 Christine Corbett, Chief Customer Officer 5 Graeme Hunt, Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer Integrated Energy Q&A 3 Markus Brokhof, Chief Operating Officer 6 • Market/operating headwinds as forecast: wholesale electricity prices and margin pressures in gas impacted earnings RESULTS • Underlying EBITDA down 18% to $1,666 million; Underlying NPAT down 34% to $537 million SUMMARY • Final ordinary dividend of 34 cents per share (fully underwritten), total dividend for the 2021 year of 75 cents, including special dividend of 10 cents • Strong customer growth: Customer services grew by 254k with continued organic growth and Click acquisition STRATEGY • Key acquisitions announced in FY21: Click, Epho, Solgen, Tilt (via PowAR) and OVO Energy Australia EXECUTION • 850 MW battery development pipeline progressing well, with FID reached on a 250 MW, grid-scale battery at Torrens Island • Shareholders granted the opportunity to vote on climate reporting at Accel Energy’s and AGL Australia’s first AGMs • Guidance for EBITDA of $1,200 to $1,400 million, subject to ongoing uncertainty, trading conditions OUTLOOK AND • Guidance for Underlying Profit after tax of $220 to $340 million, subject to ongoing uncertainty, trading conditions FY22 GUIDANCE • Operating headwinds continue into FY22: Roll off of hedging established at higher prices and non-recurrence -

9110715-REP-A-Cost and Technical

AEMO AEMO costs and technical parameter review Report Final Rev 4 9110715 September 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of this report........................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Structure of this report ......................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Acronyms and abbreviations ............................................................................................... 2 2. Scope ............................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Overview .............................................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Existing data ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Format of data ...................................................................................................................... 4 2.4 Existing generator list and parameters ................................................................................ 4 2.5 New entrant technologies and parameters ....................................................................... -

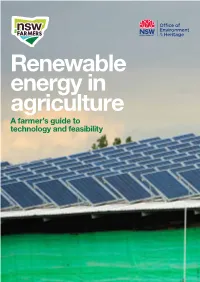

Renewable Energy in Agriculture.Pdf

Renewable energy in agriculture A farmer’s guide to technology and feasibility Renewable energy in agriculture Authors: Gerry Flores, David Eyre, David Hoffmann © NSW Farmers Association and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage All rights reserved ISBN: 978-0-9942464-0-0 Citation information: Flores G, Eyre D N, Hoffmann D, Renewable energy in agriculture: A farmer’s guide to technology and feasibility NSW Farmers, 2015 First edition, May 2015. Acknowledgements This publication has been produced by NSW Farmers with assistance from the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. Authors: Gerry Flores, David Eyre, David Hoffmann © NSW Farmers Association and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage All rights reserved ISBN: 978-0-9942464-0-0 Citation information: Flores G, Eyre D N, Hoffmann D, Renewable energy in agriculture: A farmer’s guide to technology and feasibility, NSW Farmers, 2015 Copyright and disclaimer This document: • Is copyright to NSW Farmers Association and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage • Is only intended for the purpose of assisting farmers and those interested in on- farm energy generation (and is not intended for any other purpose). While all care has been taken to ensure this publication is free from omission and error, no responsibility can be taken for the use of this information in the design or installation of any solar electric system. Cover photo: Solar PV is widely adopted in First Edition, May 2015. Australia by farmers who operate intensive facilities. A farmer’s guide to technology and feasibility 1 Contents 2. Foreword 3. About this guide 4. Overview 6. -

Clean Energy Australia 2019

CLEAN ENERGY AUSTRALIA CLEAN ENERGY AUSTRALIA REPORT 2019 AUSTRALIA CLEAN ENERGY REPORT 2019 We put more energy into your future At Equip, we’re fairly and squarely focused on generating the best possible returns to power the financial future of our members. With more than 85 years in the business of reliably delivering superannuation to employees in the energy sector, it makes sense to nominate Equip as the default fund for your workplace. Equip Super fair and square Call Tyson Adams Ph: 03 9248 5940 Mob: 0488 988 256 or email: [email protected] This is general information only. It does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and should therefore not be taken as personal advice.Equipsuper Pty Ltd ABN 64 006 964 049, AFSL 246383 is the Trustee of the Equipsuper Superannuation Fund ABN 33 813 823 017. Before making a decision to invest in the Equipsuper Superannuation Fund, you should read the appropriate Equip Product Disclosure Statement (PDS). Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Equipsuper Financial Planning Pty Ltd (ABN 84 124 491 078, AFSL 455010) is licensed to provide financial planning services to retail and wholesale clients. Equipsuper Financial Planning Pty Ltd is owned on behalf of Equipsuper Pty Ltd. CONTENTS 4 Introduction 6 2018 snapshot 12 Jobs and investment in renewable energy by state 15 Project tracker 16 Policy void risks momentum built by Renewable Energy Target 18 Industry outlook: small-scale renewable energy 19 Industry outlook: large-scale -

Clean Energy Australia 2020

CLEAN ENERGY AUSTRALIA CLEAN ENERGY AUSTRALIA REPORT 2020 AUSTRALIA CLEAN ENERGY REPORT 2020 CONTENTS 4 Introduction 6 2019 snapshot 12 Jobs and investment in renewable energy by state 15 Project tracker 16 Renewable Energy Target a reminder of what good policy looks like 18 Industry outlook: small-scale renewable energy 22 Industry outlook: large-scale renewable energy 24 State policies 26 Australian Capital Territory 28 New South Wales 30 Northern Territory 32 Queensland 34 South Australia 36 Tasmania 38 Victoria 40 Western Australia 42 Employment 44 Renewables for business 48 International update 50 Electricity prices 52 Transmission 54 Energy reliability 56 Technology profiles 58 Battery storage 60 Hydro and pumped hydro 62 Hydrogen 64 Solar: Household and commercial systems up to 100 kW 72 Solar: Medium-scale systems between 100 kW and 5 MW 74 Solar: Large-scale systems larger than 5 MW 78 Wind Cover image: Lake Bonney Battery Energy Storage System, South Australia INTRODUCTION Kane Thornton Chief Executive, Clean Energy Council Whether it was the More than 2.2 GW of new large-scale Despite the industry’s record-breaking achievement of the renewable generation capacity was year, the electricity grid and the lack of Renewable Energy Target, added to the grid in 2019 across 34 a long-term energy policy continue to projects, representing $4.3 billion in be a barrier to further growth for large- a record year for the investment and creating more than scale renewable energy investment. construction of wind and 4000 new jobs. Almost two-thirds of Grid congestion, erratic transmission solar or the emergence this new generation came from loss factors and system strength issues of the hydrogen industry, large-scale solar, while the wind sector caused considerable headaches for by any measure 2019 was had its best ever year in 2019 as 837 project developers in 2019 as the MW of new capacity was installed grid struggled to keep pace with the a remarkable year for transition to renewable energy. -

The Prospect for an Australian–Asian Power Grid: a Critical Appraisal

energies Review The Prospect for an Australian–Asian Power Grid: A Critical Appraisal Edward Halawa 1,2,*, Geoffrey James 3, Xunpeng (Roc) Shi 4,5 ID , Novieta H. Sari 6,7 and Rabindra Nepal 8 1 Barbara Hardy Institute, School of Engineering, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes, SA 5095, Australia 2 Centre for Renewable Energy, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 3 Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] 4 Australia China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] 5 Energy Studies Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 119077, Singapore 6 Department of Communication, Universitas Nasional, Jakarta 12520, Indonesia; [email protected] 7 The School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK 8 School of Economics and Finance, Massey University, Auckland Campus, Albany 0632, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-8-8302-3329 Received: 17 October 2017; Accepted: 11 January 2018; Published: 15 January 2018 Abstract: Australia is an energy net self-sufficient country rich in energy resources, from fossil-based to renewable energy. Australia, a huge continent with low population density, has witnessed impressive reduction in energy consumption in various sectors of activity in recent years. Currently, coal and natural gas are two of Australia’s major export earners, yet its abundant renewable energy resources such as solar, wind, and tidal, are still underutilized. The majority of Asian countries, on the other hand, are in the middle of economic expansion, with increasing energy consumption and lack of energy resources or lack of energy exploration capability becoming a serious challenge. -

ASX & Media Release

AGL Energy Limited Locked Bag 1837 Level 24, 200 George St T: +61 2 9921 2999 ABN: 74 115 061 375 St Leonards NSW 2065 Sydney NSW 2000 F: +61 2 9921 2552 Australia Australia www.agl.com.au ASX & Media Release AGL 2017 Annual Report 25 August 2017 AGL Energy Limited (AGL) has today commenced dispatch of its 2017 Annual Report. A copy is attached. AGL also issued its 2017 AGL Sustainability Report today. Online versions of the Annual Report and Sustainability Report are available at www.agl.com.au/2017ReportingSuite. Investor enquiries Media enquiries James Hall Chris Kotsaris Kathryn Lamond General Manager, Capital Markets Senior Manager, Investor Relations Senior Manager, Media T: +61 2 9921 2789 T: +61 2 9921 2256 T: +61 2 9921 2170 M: +61 401 524 645 M: +61 402 060 508 M: +61 424 465 464 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] About AGL AGL is committed to helping shape a sustainable energy future for Australia. We operate the country’s largest electricity generation portfolio, we’re its largest ASX-listed investor in renewable energy, and we have more than 3.6 million customer accounts. Proudly Australian, with more than 180 years of experience, we have a responsibility to provide sustainable, secure and affordable energy for our customers. Our aim is to prosper in a carbon-constrained world and build customer advocacy as our industry transforms. That’s why we have committed to exiting our coal-fired generation by 2050 and why we will continue to develop innovative solutions for our customers. -

Australia's Renewable Energy Future

Australia’s renewable energy future DECEMBER 2009 Australia’s renewable energy future Co-editors Professor Michael Dopita FAA Professor Robert Williamson AO, FAA, FRS January 2010 © Australian Academy of Science 2009 GPO Box 783, Canberra, ACT 2601 This work is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, news reporting, criticism or review. Selected passages, tables or diagrams may be reproduced for such purposes provided acknowledgement of the source is included. Major extracts of the entire document may not be reproduced by any process without written permission of the publisher. This publication is also available online at: www.science.org.au/reports/index.html ISBN 085847 280 5 Cover image: © Stockxpert Layout and Design: Nicholas Eccles Cover Design: Stephanie Kafkaris Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 1.2 Summary of development options 2. Alternative energy sources ......................................................................................6 2.1 Wind turbines 2.2 Solar thermal 2.3 Solar photovoltaic 2.4 Biomass energy 2.5 Fuel cells 2.6 Geothermal energy 2.7 Wave and tidal energy 3. The grid: Bringing the power to the people ......................................................20 3.1 The smart grid 3.2. Generation and distribution 4. Transport systems ........................................................................................................23 4.1. Passenger vehicles 4.2 -

Policies and Prospects for Renewable Energy in New South Wales Briefing Paper No 6/2014 by Andrew Haylen

Policies and prospects for renewable energy in New South Wales Briefing Paper No 6/2014 by Andrew Haylen RELATED PUBLICATIONS Electricity prices, demand and supply in NSW, NSW Parliamentary Research Service Briefing Paper 03/2014 by Andrew Haylen A tightening gas market: supply, demand and price outlook for NSW, NSW Parliamentary Research Service Briefing Paper 04/2014 by Andrew Haylen Wind Farms: regulatory developments in NSW, NSW Parliamentary Research Service e-brief 13/2012, by Nathan Wales and Daniel Montoya Key Issues in Energy, Background Paper 4/2014, by Daniel Montoya and Nathan Wales ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978-0-7313-1926-8 October 2014 © 2014 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Policies and prospects for renewable energy in New South Wales by Andrew Haylen NSW PARLIAMENTARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Environment/Planning ......................... (02) 9230 2003 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Senior Research Officer, Law ....................................................... (02) 9230 2768 Alec Bombell (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law .................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Tom Gotsis (BA, LLB, Dip Ed, Grad Dip Soc Sci) Research Officer, Law .................................................................. (02) 9230 2906 Andrew Haylen (BResEc (Hons)), Research Officer, Public Policy/Statistical Indicators ................. -

Fossil Fuel to Renewable Energy Transition Pathways

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Prioritizing mitigation efforts considering co-benefits, equity Title and energy justice: Fossil fuel to renewable energy transition pathways Author(s) Chapman, Andrew J.; McLellan, Benjamin C.; Tezuka, Tetsuo Citation Applied Energy (2018), 219: 187-198 Issue Date 2018-6-01 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/241776 © 2018 This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/; The full- text file will be made open to the public on 1 June 2020 in Right accordance with publisher's 'Terms and Conditions for Self- Archiving'; This is not the published version. Please cite only the published version. この論文は出版社版でありません。 引用の際には出版社版をご確認ご利用ください。 Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Please reference the final published version of this paper, available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.03.054 Prioritizing mitigation efforts considering co-benefits, equity and energy justice: Fossil fuel to renewable energy transition pathways Andrew J. Chapman*1, Benjamin C. McLellan2, Tetsuo Tezuka2. 1International Institute for Carbon-Neutral Energy Research (I2CNER), Kyushu University 744 Motooka Nishi-ku Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan [email protected] 2Graduate School of Energy Science, Kyoto University. Yoshida Honmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. KEYWORDS: Equity, Energy Justice, Health, Employment, Transition, Renewable Energy *Corresponding Author ABSTRACT Transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy (RE) is one of the core strategies in developing sustainable future energy systems. -

From Mining to Making: Australia's Future in Zero-Emissions Metal

From mining to making Australia’s future in zero- emissions metal Authors & acknowledgments Lead author Michael Lord, Energy Transition Hub, University of Melbourne Contributing authors Rebecca Burdon, Energy Transition Hub, University of Melbourne Neil Marshman, ex-Chief Advisor, Rio Tinto John Pye, Energy Change Institute, ANU Anita Talberg, Energy Transition Hub, University of Melbourne Mahesh Venkataraman, Energy Change Institute, ANU Acknowledgements Geir Ausland, Elkem Robin Batterham, Kernot Professor - Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Melbourne Justin Brown, Element 25 Andrew Dickson, CWP Renewables Ross Garnaut, Chair - Energy Transition Hub, University of Melbourne Key messages • Metal production causes 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, a figure that is set to rise as metal consumption increases. • By 2050 demand for many metals will grow substantially – driven partly by growth of renewable energy infrastructure that relies on a wide range of metals. • To meet increased demand sustainably, metal production must become zero-carbon. • Climate action by governments, investors and large companies mean there are growing risks to high-carbon metal production. • Companies and governments are paying more attention to the emissions embodied in goods and materials they buy. This is leading to a emerging market for lower-carbon metal, that has enormous potential to grow. • Australia has an opportunity to capitalise on this transition to zero-carbon metal. • Few countries match Australia’s potential to generate renewable energy. A 300% renewable energy target would require only 0.15% of the Australian landmass and provide surplus energy to power new industries. • By combining renewable energy resources with some of the world’s best mineral resources, Australia can become a world leader in zero-carbon metals production.