1 Kitagawa Johnny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

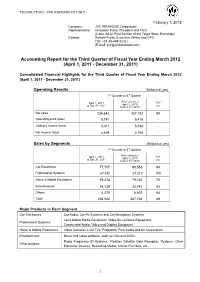

Accounting Report for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011)

TRANSLATION - FOR REFERENCE ONLY - February 1, 2012 Company: JVC KENWOOD Corporation Representative: Hisayoshi Fuwa, President and CEO (Code: 6632; First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange) Contact: Satoshi Fujita, Executive Officer and CFO (Tel: +81-45-444-5232) (E-mail: [email protected]) Accounting Report for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011) Consolidated Financial Highlights for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011) Operating Results (Millions of yen) 1st Quarter to 3rd Quarter (For reference) April 1, 2011 YoY April 1, 2010 to Dec.31, 2011 to Dec.31, 2010 (%) Net sales 236,542 267,182 89 Operating profit (loss) 8,791 9,416 - Ordinary income (loss) 6,511 6,530 - Net income (loss) 4,409 2,193 - Sales by Segments (Millions of yen) 1st Quarter to 3rd Quarter (For reference) YoY April 1, 2011 April 1, 2010 to Dec.31, 2011 to Dec.31, 2010 (%) Car Electronics 77,707 80,558 96 Professional Systems 67,142 67,210 100 Home & Mobile Electronics 59,274 79,167 75 Entertainment 28,139 33,742 83 Others 4,279 6,502 66 Total 236,542 267,182 89 Major Products in Each Segment Car Electronics Car Audio, Car AV Systems and Car Navigation Systems Land Mobile Radio Equipment, Video Surveillance Equipment, Professional Systems Commercial Audio, Video and Display Equipment Home & Mobile Electronics Video Cameras, LCD TVs, Projectors, Pure Audio and AV Accessories Entertainment Music and video software, such as CDs and DVDs Radio Frequency ID Systems, Weather Satellite Data Reception Systems, Other Other projects Electronic Devices, Recording Media, Interior Furniture, etc. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Penggemar Arashi Sebagai Pop Kosmopolitan

ADLN-PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA DAFTAR PUSTAKA Buku: Hills, Matt. 2002. Fan Cultures. New York: Routledge Jenkins, H. 2006. Pop Cosmopolitanism: Mapping Cultural Flows in an Age of Media Convergence. In Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York, NY: New York University Press. Kelly, William W. 2004. Fanning The Flames: Fans and Contemporary Culture. New York: State University of New York Lewis, Lisa A. 1992. The Adoring Audience: fanculture and popular media. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc. Moleong, Lexy J. (2007) Metodologi Penelitan Kualitatif. Bandung: PT Remaja Rosdakarya Ofset. Nagaike, Kazumi. 2012. Johnny‟s Idols as Icons: Female Desires to Fantasize and Consume Male Idol Images. In Patrick Galbraith (Ed.), Idols and Celebrities in Japanese Media Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Ruslan, Rosady. 2008. Metodologi Penelitian Public Relations dan Komunikasi. Jakarta: PT. Raja Grafindo Persada Stevens, C. S. 2004. Buying Intimacy: Proximity and Exchange at a Japanese Rock Concert. In William W. Kelly (Ed.), Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan. New York: State University of New York Press. Stevens, C. S. (2008). Japanese Popular Music: Culture, Authenticity, and Power. London: Routledge Sugiyono. 2010. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif Kualitatif dan R & D. Bandung : Alfabeta Yano, C. R. 2004. Letters From The Heart: Negotiating Fan-Star Relationship in Japanese Popular Music. In William W. Kelly (Ed.), Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan. New York: State University of New York Press 87 SKRIPSI PENGGEMAR ARASHI SEBAGAI POP KOSMOPOLITAN.... RATU ADDINA YU'MINA ADLN-PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA Penelitian: 龐 惠潔 (2011) :「ファンコミュニティにおけるヒエラルキーの考察―台湾のジャ ニーズファンを例に―」 東京 東京大学 Anuar, R., Redzuan R. -

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk Kunstner Listen

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk kunstner Listen Stacy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stacy-3503566/albums The Idan Raichel Project https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/the-idan-raichel-project-12406906/albums Mig 21 https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mig-21-3062747/albums Donna Weiss https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/donna-weiss-17385849/albums Ben Perowsky https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ben-perowsky-4886285/albums Ainbusk https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ainbusk-4356543/albums Ratata https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ratata-3930459/albums Labvēlīgais Tips https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/labv%C4%93l%C4%ABgais-tips-16360974/albums Deane Waretini https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/deane-waretini-5246719/albums Johnny Ruffo https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/johnny-ruffo-23942/albums Tony Scherr https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tony-scherr-7823360/albums Camille Camille https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/camille-camille-509887/albums Idolerna https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/idolerna-3358323/albums Place on Earth https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/place-on-earth-51568818/albums In-Joy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/in-joy-6008580/albums Gary Chester https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gary-chester-5524837/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Taking Note Cover Star

WHERE IS THE LOVE? The Story behind Japan’s Frozen Population Growth TAKING NOTE Global Perspectives and New Designs in Education COVER STAR Songstress May J Breaks Through with “Let It Go” ALSO: A Chocolate Movement Comes to Tokyo, Valentine’s Gift Guide, Art around Town, Agenda, Movies,www.tokyoweekender.com and more... FEBRUARY 2015 Your Move. Our World. C M Y CM MY CY Full Relocation CMY K Services anywhere in the world. Asian Tigers Mobility provides a comprehensive end-to-end mobility service tailored to your needs. Move Management – office, households, Tenancy Management pets, vehicles Family programs Orientation and Cross-cultural programs Departure services Visa and Immigration Storage services Temporary accommodation Home and School search Asian Tigers goes to great lengths to ensure the highest quality service. To us, every move is unique. Please visit www.asiantigers-japan.com or contact us at [email protected] Customer Hotline: 03-6402-2371 FEBRUARY 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com Your Move. Our World. FEBRUARY 2015 CONTENTS 10 C MAY J. M How letting go and learning to love the Y cover song rekindled a music career CM MY CY Full Relocation 7 14 18 CMY K Services anywhere in the world. Asian Tigers Mobility provides a comprehensive end-to-end mobility service tailored to your needs. Move Management – office, households, Tenancy Management LEXUS TEST DRIVE TOKYOFIT BEAN-TO-BAR CHOCOLATE pets, vehicles Family programs Pernod Ricard Japan CEO Tim Paech takes Getting in touch with your inner child— Bringing a chocolate revolution -

Virtual Celebrities and Consumers: a Blended Reality

Virtual Celebrities and Consumers: A Blended Reality How virtual celebrities are consumed in the East and West Author: Thuy Duong Hoang (115821) Yidan Su (115392) Supervisor: Claus Springborg Master’s Thesis, MSocSc Management of Creative Business Processes Copenhagen Business School Date of submission: May 15, 2019 Pages: 117 (31.960 words, 202.544 characters) excl. front page, bibliography and appendix Abstract The goal of this study is to research how virtual celebrities are consumed in the East and West. The digital revolution has led to a surge in circulation of information. This has contributed to the transformation of human attention from an innate information gathering tool to a profitable resource, paving the way for the economy of attention. Therefore, it is significant for marketers and companies to understand how to attract attention. As celebrities enjoy large amounts of attention, they have been widely used in endorsement campaigns. Yet, their human flaws can still lead to scandals. Therefore, we argue that virtual celebrities can be used as an alternative. They are a new type of celebrity, who are able to perform ‘real life’ activities and earn money. Examples from the East include the virtual singer Hatsune Miku and the virtual YouTuber Kizuna AI, while the West is represented by the virtual band Gorillaz, or virtual model Lil Miquela, among others. A descriptive approach is used to describe the preferences of Eastern and Western consumers in context of virtual celebrities. Our research philosophy consists of objectivism and positivism. Applying a deductive research strategy, we draw hypotheses from literature, which will be tested using quantitative methods. -

Date April 26, 2013 Case Number 2009 (Wa) 26989 Court Tokyo

Date April 26, 2013 Court Tokyo District Court, Case number 2009 (Wa) 26989 47th Civil Division – A case in which the court found that the defendant's use of the photos of the plaintiffs, who are members of idol groups, in books without their authorization, infringed what is generally known as the publicity rights of the plaintiffs and is illegal under the tort law. In conclusion, the court upheld the plaintiffs' claims for an injunction against the publishing and sale of these books, and for the disposal of said books, and also partially upheld their claims for damages. In this case, the plaintiffs, who are members of idol groups, alleged that the defendant published and sold books while using the plaintiffs' photos in these books without their authorization, and thereby infringed their rights to exclusively use the customer appeal of their portraits, etc., as well as what is generally known as portrait rights. Accordingly, the plaintiffs sought an injunction against the publishing and sale of these books, demanded the disposal of said books, and claimed damages. In accordance with the gist of the judgment of the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of February 2, 2012, Minshu Vol. 66, No. 2, at 89, the court referred to a person's right to exclusively use the customer appeal of his/her own portrait, etc. as a publicity right and stated that this right is one of the rights derived from a right of personality. The court then held that "the unauthorized use of portraits, etc. of a person is considered to be infringement of the person's publicity right and is found to be illegal under the tort law if the sole purpose of the use is to take advantage of the customer appeal of the portraits, etc. -

El Colegio De México EL MERCADO DE IDOL VARONES EN JAPÓN

El Colegio de México EL MERCADO DE IDOL VARONES EN JAPÓN (1999 – 2008): CARACTERIZACIÓN DE LA OFERTA A TRAVÉS DEL ESTUDIO DE UN CASO REPRESENTATIVO Tesis presentada por YUNUEN YSELA MANDUJANO SALAZAR en conformidad con los requisitos establecidos para recibir el grado de MAESTRÍA EN ESTUDIOS DE ASIA Y ÁFRICA ESPECIALIDAD JAPÓN Centro de Estudios de Asia y África 2009 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN……………………………………………………………………. 3 I. FENÓMENO IDOL EN JAPÓN Y OBJETO DE ESTUDIO………………... 14 1. Desarrollo general de la industria idol……………………………………. 14 2. Definición de idol………………………………………………………… 18 3. La compañía Johnny’s Jimusho………………………………………….. 22 4. Arashi…………………………………………………………………….. 31 II. ESTRATEGIAS DE DESARROLLO DEL MERCADO IDOL…………….. 36 1. Primera etapa: Base junior, reclutamiento y formación…………………. 37 2. Segunda etapa: Lanzamiento y consolidación de mercado………………. 46 3. Tercera etapa: Diversificación y expansión de mercado…………………. 58 III. SITUACIÓN ACTUAL DEL MERCADO DE IDOL VARONES………….. 68 1. El dominio idol dentro de la industria musical en Japón…………………. 69 2. Fin del monopolio y cambio de estrategias en el mercado de idol varones en Japón……………………………………………………………………… 75 CONCLUSIONES……………………………………………………………………. 84 REFERENCIAS………………………………………………………………………. 88 ANEXOS……………………………………………………………………………… 98 1 NOTA SOBRE EL SISTEMA DE ROMANIZACIÓN UTILIZADO En el presente estudio se utilizará, para los términos generales y los nombres de ciudades, el sistema de romanización usado en el Kenkyusha’s New Japanese – English Dictionary (3ra y ediciones posteriores). En el caso de nombres propios de origen japonés, se presentará primero el nombre y luego el apellido y se utilizará la romanización utilizada en las fuentes originales. Asimismo, es común que los autores no utilicen el macron (¯ ) cuando existe una vocal larga en este tipo de denominaciones. -

L'intertestualità Mediatica Del Johnny's Jimusho

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e civiltà dell'Asia e dell'Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea L’intertestualità mediatica del Johnny’s Jimusho Relatore Ch. Prof.ssa Maria Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof.ssa Paola Scrolavezza Laureando Myriam Ciurlia Matricola 826490 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 A papà. RINGRAZIAMENTI Ringrazio la mia famiglia: mio papà, che per anni e anni mi ha ascoltata mentre parlavo di Johnny’s , Yamapi, “Jin-l’odioso ” e di Giappone e passioni. Per aver sognato con me, sostenuto le mie scelte e aver avuto più fiducia in me di quanta ne abbia io. Alla mamma che mi ha costretta a giudicare oggettivamente le mie scelte, anche quando non volevo, e mi ha aiutata in cinque anni di studi fuori sede. Le mie cugine, Jessica, per la sua amicizia e Betty, per i suoi consigli senza i quali questa tesi oggi sarebbe molto diversa. Ringrazio mio nonno, per le sue premure e la sua pazienza quando dicevo che sarebbero passati in un baleno, quei mesi in Giappone o quell’anno a Venezia. La nonna, per il suo amore e le sue attenzioni. Le piccole Luna e Sally, per avermi tenuto compagnia dormendo sulle mie gambe quando studiavo per gli esami e per i mille giochi fatti insieme. Ringrazio le mie coinquiline: Ylenia, Caterina, Alessandra, Dafne, Veronica M. e Veronica F. Per le serate passate a guardare il Jersey Shore o qualche serie TV assurda e tutte le risate, la camomilla che in realtà è prosecco, le pulizie con sottofondo musicale, da Gunther a Édith Piaf. Per le chiacchierate fatte mentre si cucinava in quattro in una cucina troppo piccola, per le ciambelle alle sei del mattino prima di un esame e tutte le piccole gentilezze quotidiane.