Why Does Illegal Broadcasting Continue to Thrive in the Age of Liberalised Spectrum?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ofcom Annual Report on Community Radio Fund 2019-20 (PDF, 240.5

Community Radio Fund End of year report: 2019/20 Annual report of Community Radio Fund – Welsh overview Publication date: 17 July 2020 Contents Section 1. Overview 1 2. Community Radio Fund End of Year Report 2019/20 2 Annex A1. Awards to stations in 2019/20 6 Community Radio Fund 1. Overview This document reports on how the Community Radio Fund was administered in 2019/20. Ofcom has been tasked by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) with administering a Community Radio Fund. DCMS provides a sum of money each year for the Fund and grants are awarded to Ofcom-licensed community radio stations. The report sets out how much money was given out as grants, which stations received grants and for what purposes grants were awarded. 1 Community Radio Fund 2. Community Radio Fund End of Year Report 2019/20 2.1 The Community Radio Fund (‘the Fund’) exists to help community radio licensees and to support core costs incurred in the provision of community radio services. 2.2 Ofcom administers the Fund on behalf of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The money allocated to the Fund is given out in the form of grants, following a formal application process. 2.3 The decisions on grant applications are made by the Community Radio Fund Panel (‘the Panel’), which reports to the Ofcom Policy and Management Board.1 2.4 DCMS allocated £400,000 to the Fund for the financial year 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. In addition, DCMS allocated a further £30,448 to the Fund for the second round. -

EDMTCC 2014 – the EDM Guide

EDMTCC 2014 F# The EDM Guide: Technology, Culture, Curation Written by Robby Towns EDMTCC.COM [email protected] /EDMTCC NESTAMUSIC.COM [email protected] @NESTAMUSIC ROBBY TOWNS AUTHOR/FOUNDER/ENTHUSIAST HANNAH LOVELL DESIGNER LIV BULI EDITOR JUSTINE AVILA RESEARCH ASSISTANT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SIMON MORRISON GOOGLE VINCENT REINDERS 22TRACKS GILLES DE SMIT 22TRACKS LUKE HOOD UKF DANA SHAYEGAN THE COLLECTIVE BRIAN LONG KNITTING FACTORY RECORDS ERIC GARLAND LIVE NATION LABS BOB BARBIERE DUBSET MEDIA HOLDINGS GLENN PEOPLES BILLBOARD MEGAN BUERGER BILLBOARD THE RISE OF EDM 4 1.1 SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST 6 1.2 DISCO TO THE DROP 10 1.3 A REAL LIFE VIDEO GAME 11 1.4 $6.2 BILLION GLOBAL INDUSTRY 11 1.5 GOING PUBLIC 13 1.6 USB 14 TECHNOLOGY: 303, 808, 909 15 2.1 ABLETON LIVE 18 2.2 SERATO 19 2.3 BEATPORT 21 2.4 SOUNDCLOUD 22 2.5 DUBSET MEDIA HOLDINGS 23 CULTURE: BIG BEAT TO MAIN STREET 24 3.1 DUTCH DOMINANCE 26 3.2 RINSE FM 28 3.3 ELECTRIC DAISY CARNIVAL 29 3.4 EDM FANS = HYPERSOCIAL 30 CURATION: DJ = CURATOR 31 4.1 BOOMRAT 33 4.2 UKF 34 4.3 22TRACKS 38 BONUS TRACK 41 THE RISE OF EDM “THE MUSIC HAS SOMETHING IN COMMON WITH THE CURRENT ENGLISH- SYNTHESIZER LED ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC...” –LIAM LACEY, CANADIAN GLOBE & MAIL 1982 EDMTCC.COM What is “EDM”? The answer from top brands, and virtually to this question is not the every segment of the entertain- purpose of this paper, but is ment industry is looking to cap- a relevant topic all the same. -

Federal Communications Commission Enforcement Bureau Office of the Field Director

Federal Communications Commission Enforcement Bureau Office of the Field Director 45 L Street, NE Washington, DC 20554 [email protected] December 17, 2020 BY FIRST-CLASS MAIL AND CERTIFIED MAIL BRG 3512 LLC KRR Queens 1 LLC BRG Management LLC 150 Great Neck Road, Suite 402 Great Neck, New York 11021 ATTN: Jonah Rosenberg NOTICE OF ILLEGAL PIRATE RADIO BROADCASTING Case Number: EB-FIELDNER-17-00024174 The New York Office of the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Enforcement Bureau is investigating a complaint about an unlicensed FM broadcast station operating on the frequency 95.9 MHz. On November 14, 2020, agents from the New York Office confirmed by direction-finding techniques that radio signals on frequency 95.9 MHz were emanating from the property at 3512 99th Street, Queens, New York. Publicly available records identify BRG 3512 LLC and KRR Queens 1 LLC as joint owners of the property at 3512 99th Street, Queens, New York, and BRG Management LLC as the site’s property manager.1 The FCC’s records show no license issued for operation of a radio broadcast station on 95.9 MHz at that location. Radio broadcast stations operating on certain frequencies,2 including 95.9 MHz, must be licensed by the FCC pursuant to the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (Act).3 While the FCC’s rules create exceptions for certain extremely low-powered devices, our agents have determined that those exceptions do not apply to the transmissions they observed originating from the property. Accordingly, the station operating on the property identified above -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

Press Release

! Artist: Skream Title: FABRICLIVE 96: Skream Label: fabric Records Cat. #: fabric192 Format: CD & Digital - Pre-Order !Release Date: 19 January 2018 As a pioneering force during the emergence of dubstep in a tight-knit South London scene, Oliver Jones’ career has taken him from local hero to world renowned DJ. His productions are credited with introducing an esoteric sound to a global audience and for more than a decade he has continued to expand his palette into new territory, both on his own and as part of Magnetic Man with Benga and Artwork. From 2006 onwards his ‘Stella Sessions’ on Rinse FM became a platform for devoted fans to hear new material, much of which can be traced onto forums and Youtube rips across the web. On a legendary radio station that still serves as one of the key platforms for underground music in the UK, he sustained a reputation as a tastemaker presenting the latest sought-after dubs, many of which came from his close friends. A prolific producer, he has acclaimed EPs and albums on Tempa, Tectonic, Big Apple, Soul Jazz, Exit, Digital Soundboy, Greco-Roman and Harmless amongst others, as well as his own Disfigured Dubz imprint. In 2010 he formed the Skream & Benga radio show alongside his closest contemporary, which paved the way for a two year residency on BBC Radio 1 documenting a broader variety of styles. He is now a regular on the global DJ circuit, touring a wide range of venues and festivals the year round. FABRICLIVE 96 is a playful journey through the house, techno and disco he has explored in more recent years. -

Making Radio Pirates Walk the Plank with Aiding and Abetting Liability

Arrr! Sever Thee Transmitters! Making Radio Pirates Walk the Plank with Aiding and Abetting Liability Max Nacheman * TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 299 II. THE INTERTWINED FATE OF BROADCAST REGULATION AND PIRATE RADIO ............................................................................................. 301 A. Origins of Radio Broadcast Regulation in the United States .. 301 B. Pirates of the (Air)waves: The Swell of Unauthorized Broadcasting ............................................................................ 303 C. From Radio Pirates to Cellular Ninjas: The Future of Unauthorized Broadcasting ..................................................... 304 III. UNAUTHORIZED BROADCASTING POSES A UNIQUE ENFORCEMENT CHALLENGE THAT MAY BE ADDRESSED BY ESTABLISHING AUTHORITY TO CRACK DOWN ON AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF PIRATE BROADCASTERS .............................................................................. 305 A. The FCC’s Enforcement Procedure for Unauthorized Broadcasters Is an Inadequate Deterrent to Pirates ............... 306 B. Aiding and Abetting Liability Would Cut the Supply Chain of Essential Resources to Unauthorized Broadcasters ................ 309 1. How the United Kingdom Sank Pirate Radio ................... 310 2. Aiding and Abetting Liability for Securities Violations ... 311 IV. THREE WAYS TO CRACK DOWN ON AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF UNAUTHORIZED BROADCASTING: STATUTE, RULEMAKING, AND EXISTING CRIMINAL LAW ............................................................. -

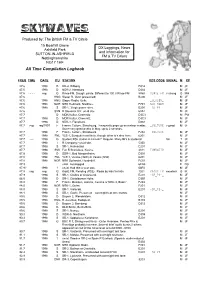

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

Redefining Radio Art in the Light of New Media Technology Through

Title Radio After Radio: Redefining radio art in the light of new media technology through expanded practice Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/8748/ Date 2015 Citation Hall, Margaret A. (2015) Radio After Radio: Redefining radio art in the light of new media technology through expanded practice. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Creators Hall, Margaret A. Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author 1 Margaret Ann Hall Radio After Radio: Redefining radio art in the light of new media technology through expanded practice Thesis for PhD degree awarded by the University of the Arts London June 2015 2 Abstract I have been working in the field of radio art, and through creative practice have been considering how the convergence of new media technologies has redefined radio art, addressing the ways in which this has extended the boundaries of the art form. This practice- based research explores the rich history of radio as an artistic medium and the relationship between the artist and technology, emphasising the role of the artist as a mediator between broadcast institutions and a listening public. It considers how radio art might be defined in relation to sound art, music and media art, mapping its shifting parameters in the digital era and prompting a consideration of how radio appears to be moving from a dispersed „live‟ event to one consumed „on demand‟ by a segmented audience across multiple platforms. -

Diverse on Screen Talent Directory

BBC Diverse Presenters The BBC is committed to finding and growing diverse onscreen talent across all channels and platforms. We realise that in order to continue making the BBC feel truly diverse, and improve on where we are at the moment, we need to let you know who’s out there. In this document you will find biographies for just some of the hugely talented people the BBC has already been working with and others who have made their mark elsewhere. It’s the responsibility of every person involved in BBC programme making to ask themselves whether what, and who, they are putting on screen reflects the world around them or just one section of society. If you are in production or development and would like other ideas for diverse presenters across all genres please feel free to get in touch with Mary Fitzpatrick Editorial Executive, Diversity via email: [email protected] Diverse On Screen Talent Directory Presenter Biographies Biographies Ace and Invisible Presenters, 1Xtra Category: 1Xtra Agent: Insanity Artists Agency Limited T: 020 7927 6222 W: www.insanityartists.co.uk 1Xtra's lunchtime DJs Ace and Invisible are on a high - the two 22-year-olds scooped the gold award for Daily Music Show of the Year at the 2004 Sony Radio Academy Awards. It's a just reward for Ace and Invisible, two young south Londoners with high hopes who met whilst studying media at the Brits Performing Arts School in 1996. The 'Lunchtime Trouble Makers' is what they are commonly known as, but for Ace and Invisible it's a story of friendship and determination. -

Transnationalizing Radio Research

Golo Föllmer, Alexander Badenoch (eds.) Transnationalizing Radio Research Media Studies | Volume 42 Golo Föllmer, Alexander Badenoch (eds.) Transnationalizing Radio Research New Approaches to an Old Medium . Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2018 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Maria Arndt, Bielefeld Typeset: Anja Richter Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-3913-1 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-3913-5 Contents INTRODUCTION Transnationalizing Radio Research: New Encounters with an Old Medium Alexander Badenoch -

Illegal Broadcasting

Illegal broadcasting: How pirates harm broadcasting Illegal broadcasting is a serious criminal and anti-social activity. The pirates who broadcast without a licence risk causing harmful interference to communications services used by the emergency services and are a nuisance to legal broadcasters. They can also have a negative impact on the local communities to which they illegally broadcast. What is Ofcom? What is illegal broadcasting? Broadcasting as a radio station requires a licence. Ofcom is the UK communications regulator. Illegal broadcasting, otherwise known as pirate radio, One of our duties is to protect and manage the is the operation of an unlicensed and unregulated airwaves, or radio spectrum, which we rely upon radio station. There are about a hundred illegal without always knowing it. stations in the UK with around three quarters based A vast range of devices and services use this in London. Their apparatus is often installed on high- spectrum, including our mobile phones, broadcast rise local authority owned residential buildings. TV and radio, as well as communications networks for the emergency services. But spectrum is a finite and valuable resource that needs protection from interference. This includes Illegal broadcast facts taking steps to address illegal broadcast stations and the harmful effects they cause. • Ofcom responded to 26 cases of interference to critical radio communications in 2013. We Unless an exemption applies, using spectrum received 344 other complaints about illegal requires a licence from Ofcom. Ofcom issues broadcast stations. spectrum licences to more than 300,000 individuals and organisations for business, • Those involved in illegal broadcasting have social and safety applications, which they used violence and intimidated Ofcom staff, local use legitimately. -

In Support of the Pirate Act

Statement of David L. Donovan President and Executive Director New York State Broadcasters Association, Inc. IN SUPPORT OF THE PIRATE ACT Before the Energy and Commerce Committee Subcommittee on Communications & Technology U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC March 22, 2018 Executive Summary The New York State Broadcaster’s Association, Inc. and the National Association of Broadcasters strongly support the PIRATE Act, which combats the growing problem of illegal pirate radio stations. In New York City and Northern New Jersey alone, the number of illegal pirate radio stations exceeds the number of licensed stations. But this has become a nationwide issue. Illegal pirate radio stations harm the public in several ways: • Pirates undermine the Emergency Alert System (EAS) • Pirates threaten public health by exposing to RF radiation • Pirate stations interfere with airport communications • Pirates ignore federal and state consumer protection laws • Pirate ignore all FCC engineering, public interest and political broadcast rules The PIRATE Act gives the FCC additional tools to address the growing pirate radio problem. It significantly increases fines to a maximum of $2 million and $100,000 per violation. Upon prior notice, it holds liable persons, including property owners, who “knowingly” facilitate illegal pirate operations. It gives the FCC the ability to go to Federal District court and obtain court orders to seize equipment. The PIRATE Act streamlines the enforcement process. It also authorizes the FCC to seize illegal pirate radio equipment if it discovers someone broadcasting illegally in real time. Finally, the PIRATE Act requires the FCC to conduct pirate radio enforcement sweeps in cities with a concentration of pirate radio stations.