Protecting Pensions Against Scams: Priorities for the Financial Guidance and Claims Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Briefing

2015 Issue 3 (Publ. June 1) Vol. 9 Issue 3 A round up of policy events and news 1. Top story - General Election & Queen’s Speech Queen’s Speech – New legislative programme The Queen’s Speech sets out the Government’s legislative agenda, which this year consists of twenty six Bills. The first Conservative Queen’s Speech since 1996 contains few surprises as the proposed legislation reflects the Conservative’s pre-election manifesto commitments, such as a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, no rises in national insurance, income tax or VAT over the next five years, and extending Right to Buy to housing association tenants. There are four constitutional Bills devolving power away from Westminster. A consultation will be held on the move to replace the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights. Bills of interest include: Scotland Bill This Bill will deliver, in full, the Smith Commission agreement on further devolution to Holyrood, including responsibility for setting levels of income tax. European Referendum Bill The EU referendum was a key part of the Conservative’s election campaign and this Bill will provide for a referendum of Britain’s membership of the EU. The vote will take place before the end of 2017. Enterprise Bill The Enterprise Bill seeks to cut business regulation and enable easier resolution of disputes for small businesses. Bank of England Bill The purpose of the Bill is to strengthen further the governance and accountability of the Bank of England to ensure it is well-positioned to oversee monetary policy and financial stability. -

House of Lords Minute

REGISTER OF LORDS’ INTERESTS _________________ The following Members of the House of Lords have registered relevant interests under the code of conduct: ABERDARE, LORD Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director, F.C.M. Limited (recording rights) Category 10: Non-financial interests (c) Trustee, National Library of Wales Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Trustee, Stephen Dodgson Trust (promotes continued awareness/performance of works of composer Stephen Dodgson) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Sesquicentenary Committee (music) Director, UK Focused Ultrasound Foundation (charitable company limited by guarantee) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Society Trustee, West Wycombe Charitable Trust ADAMS OF CRAIGIELEA, BARONESS Nil No registrable interests ADDINGTON, LORD Category 1: Directorships Chairman, Microlink PC (UK) Ltd (computing and software) Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director and Trustee, The Atlas Foundation (registered charity; seeks to improve lives of disadvantaged people across the world) Category 10: Non-financial interests (d) President (formerly Vice President), British Dyslexia Association Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Vice President, UK Sports Association Vice President, Lakenham Hewitt Rugby Club (interest ceased 30 November 2020) ADEBOWALE, LORD Category 1: Directorships Director, Leadership in Mind Ltd (business activities; certain income from services provided personally by the member is or will be paid to this company; see category 4(a)) Director, Visionable Limited (formerly IOCOM UK -

Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons from British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2015 Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform, 55 Santa Clara L. Rev. 323 (2015). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAMING THE "FERAL BEAST"1 : CAUTIONARY LESSONS FROM BRITISH PRESS REFORM Lili Levi* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introdu ction ............................................................................ 324 I. British Press Reform, in Context ....................................... 328 A. Overview of the British Press Sector .................... 328 B. The British Approach to Newspaper Regulation.. 330 C. Phone-Hacking and the Leveson Inquiry Into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press ..... 331 D. Where Things Stand Now ...................................... 337 1. The Royal Charter ............................................. 339 2. IPSO and IM -

Dr. Ros Altmann

DR. ROS ALTMANN PROFILE • • Independent consultant on pensions, savings and investment policy • • Policy adviser to Government on pensions, retirement, savings and investment • issues • • Investment professional with 20 years’ investment experience • • Wide range of investment expertise, including equity analysis, global equity • strategy, asset allocation, venture capital and hedge fund strategy • • Academic researcher on pension policy, occupational pensions and retirement • • Non-Executive Director and Governor of the London School of Economics CAREER DETAILS LORD CHANCELLOR’S STRATEGIC INVESTMENT BOARD May 2004 to date Public appointment as Member of the Strategic Investment Board of the Lord Chancellor’s Office. Advising on investment matters for over £5.5 billion of assets for the Public Guardianship Office, Official Court Funds, Official Solicitor and other bodies. INDEPENDENT CONSULTANT – INVESTMENT STRATEGY 1993 to date Strategic consultancy to investment companies on wide range of issues, including hedge fund strategy, asset allocation, venture capital and valuation of smaller companies. Clients include 3i, MAN Group, HM Treasury, International Asset Management, BBC. POLICY ADVISORY WORK - PENSIONS/INVESTMENT/SAVINGS 2000 to date Policy adviser to Number 10 Policy Unit on savings, pensions and retirement policy. Researching, writing and speaking on policy issues for pensions, lifetime savings, investments and annuities. Involved in policy initiatives to encourage middle income groups to save. CONSULTANT TO MYNERS REVIEW OF INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT Apr-Sep 2000 Consultant to UK Treasury on this major Review of institutional investment. Identified areas of inquiry and produced in-depth analysis and policy recommendations on institutional investment. NATWEST INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT DIRECTOR 1991-1993 Global Equity Strategist. Responsible for Global Equity Strategy of all funds under active management. -

1 Hm Treasury Ministers Quarterly Information

HM TREASURY MINISTERS QUARTERLY INFORMATION: 1 APRIL – 30 JUNE 2014 GIFTS GIVEN OVER £140 The Rt Hon George Osborne MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil return The Rt Hon Danny Alexander MP, Chief Secretary to the Treasury Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil return David Gauke MP, Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil return Lord Deighton, Commercial Secretary to the Treasury Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil return Sajid Javid MP, Financial Secretary to the Treasury (1 April - 9 April 2014) Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil return Andrea Leadsom MP, Economic Secretary to the Treasury (9 April - 30 June) Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil return 1 GIFTS RECEIVED OVER £140 The Rt Hon George Osborne MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return The Rt Hon Danny Alexander MP, Chief Secretary to the Treasury Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return David Gauke MP, Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return Lord Deighton, Commercial Secretary to the Treasury Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return Sajid Javid MP, Financial Secretary to the Treasury (1 April - 9 April 2014) Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return Andrea Leadsom MP, Economic Secretary to the Treasury (9 April – 30 June) Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return 2 HOSPITALITY RECEIVED1 The Rt Hon George Osborne -

TTF 100Th Ambassador

Transparency Task Force appoints Baroness Ros Altmann CBE as its 100th Ambassador as it publishes report on ‘Rebuilding Trust and Confidence in Financial Services’ Embargoed until 07:00am, 16th May 2019, London: The Transparency Task Force (“TTF”), the collaborative campaigning community dedicated to driving up the levels of transparency, truthfulness and trustworthiness in the financial services sector, has appointed Baroness Ros Altmann CBE as its 100th Ambassador. Baroness Altmann is a leading authority on later life issues, including pensions, social care and retirement policy. Numerous major awards have recognised her work to demystify finance and make pensions work better for people. She was the UK Pensions Minister from 2015 - 16 and is a member of the House of Lords, where she sits as Baroness Altmann of Tottenham. Baroness Altmann commented: “I have spent many years trying to improve the way the pension system works and to make pensions work better for people. There have been significant steps forward over the years such as the creation of the Pension Protection Fund; and of course, pensions auto-enrolment which has been a major success so far. However, we are a long way from the end game, because the possibility of widespread pensioner poverty still exists. “The vast majority of workers are in defined contribution schemes, where the level of contributions, investment returns and charges will determine their future pensions. “It’s now mission-critical that the pensions industry works harder to improve engagement and contributions, while building trust and confidence with products and services that offer good value for customers.” Baroness Altmann has been campaigning for greater transparency on costs and charges for over ten years and more recently, she has highlighted the Net Pay/Relief at Source scandal that affects the lowest earners, and the urgent need to address error rates in auto- enrolment data, so that a reliable Pensions Dashboard can be delivered. -

At Work Designing a Company Fit for the Future

WOMEN AT WORK DESIGNING A COMPANY FIT FOR THE FUTURE 1 FOREWORD The sight of Carolyn Fairbairn and Frances O’Grady touring the TV studios with a joint message for the prime minister on the “national emergency” of a no-deal Brexit, was heartening – even if Theresa May was not listening. ‘These women are doing things differently,’ I thought, unprecedented as it is for the leader of the employer’s organisation, the CBI, to join forces with the head of the Trades Union Congress. I would like to think that women could collaborate and co-operate more like Mses Fairbairn and O’Grady if they were able to work in ways that came more naturally to them. This might give us a more sustainable, caring form of capitalism than the current winner- takes-all approach to the economy that has been fostered by men in charge. Deborah Hargreaves There are already many women out there who are attempting to Friends Provident do things differently. In the wake of the #MeToo movement lots Foundation journalist of women have been re-assessing their approach to work. They fellow are being helped along by a proliferation of writing about women and jobs, leadership and the economy. From retail consultant and broadcaster, Mary Portas Work Like A Woman where she writes about rebuilding her business on values such as collaboration, empathy and trust, to feminist campaigner, Caroline Criado Perez Invisible Women about a world largely built for and by men. We seem to be waking up to the fact that the female approach, women’s views and characteristics such as inclusion and empathy are just as important as those of men and it is high time they were recognised. -

Media Coverage of the Independent Review of Retirement Income’S Report Entitled We Need a National Narrative: Building a Consensus Around Retirement Income

Media Coverage of the Independent Review of Retirement Income’s report entitled We Need a National Narrative: Building a Consensus around Retirement Income Pensions study gives ‘work till you drop’ warning, Josephine Cumbo, Pensions Correspondent, Financial Times, March 2, 2016 A new generation faces “working until they drop” unless sweeping changes are made to the UK’s pensions system, according to an independent review. The scathing assessment follows the government reforms that gave savers freedom to spend their pensions pots as they wished. The two-year study, commissioned by the Labour party, found that since “pension freedoms” were introduced, savers were exposed to risks they did not understand and should not be expected to manage themselves. “Until recently, the only purpose of a pension scheme was to provide lifetime income security,” said Professor David Blake, chair of the Independent Review of Retirement Income and director of the Pensions Institute at Cass Business School. “Nobody knows what a good outcome looks like since the pension freedoms. The danger now is we will have a generation who really can’t afford to retire.” The report said there were “serious question marks” over the effectiveness and cost of the alternatives offered by the investment management industry, since the requirement to buy an annuity was scrapped in 2015. “The insurance industry is relying on customer inertia rather than good valued decumulation [converting pensions into income] products to capture market share,” said the report. Nobody knows what a good outcome looks like since the pension freedoms. The danger now is we will have a generation who really can’t afford to retire. -

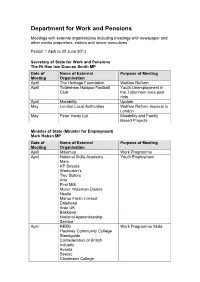

Department for Work and Pensions: Meetings with External

Department for Work and Pensions Meetings with external organisations including meetings with newspaper and other media proprietors, editors and senior executives1 Period: 1 April to 30 June 2013 Secretary of State for Work and Pensions The Rt Hon Iain Duncan Smith MP Date of Name of External Purpose of Meeting Meeting Organisation April The Heritage Foundation Welfare Reform April Tottenham Hotspur Football Youth Unemployment in Club the Tottenham area post riots April Motability Update May London Local Authorities Welfare Reform Impacts in London May Peter Vardy Ltd Motability and Family Based Projects Minister of State (Minister for Employment) Mark Hoban MP Date of Name of External Purpose of Meeting Meeting Organisation April Maximus Work Programme April National Skills Academy Youth Employment Mars KP Snacks Warburton’s Two Sisters Arla First Milk Muller Wiseman Dairies Nestle Manor Fresh Limited Dalehead Ardo UK Bakkavor National Apprenticeship Service April REED Work Programme Skills Hackney Community College Standguide Confederation of British Industry Avanta Seetec Chichester College Date of Name of External Purpose of Meeting Meeting Organisation Prospectus Career Development Group Uxbridge College Interserve Bradford Council Association of Colleges Association of Employment & Learning Providers A4E ESG AoC Network for Europe E London Advanced Technology Training Enable V Learning Net Intraining Eosworks Ingeus General Physics Pertemps People Development Group New College Durham Serco Employment Related Services Association -

UK Government One Month After Brexit

UK Government One Month After Brexit UKSIF member policy update Introduction Contents One month on, the aftermath of Brexit has been not just a new Prime Minister, but a new look government and a complete shake- Introduction 1 up of Whitehall. The reorganisation of the machinery of government Theresa May and Number 10 2 will affect all sectors, including RI. HM Treasury 3 This brief outlines the recent changes including key departments, personnel and where available their views on responsible Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 4 investment. Department for Work and Pensions 5 Department for Communities and Local Government 6 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 6 Department for Exiting the European Union 6 NB: All information is accurate as of 27th July. Only key departments and ministers are included in this brief. Department for International Trade 6 1 | P a g e Prime Minister – Rt Hon Theresa May MP Following her win in the surprisingly brief Conservative leadership contest, Theresa May became Prime Minister on the 13th July. In her first speech following her appointment she was clear that “Brexit means Brexit” but also vowed to “build a better Britain not just for the privileged few”, a clear indication of her intent to plant a Conservative flag in the political centre ground. Part of this vision includes a raft of measures to reform the UK’s corporate governance regime which she initially outlined during the leadership contest. This included taking steps to ensure both a company’s workforce and consumers were represented on boards. The section of her speech, entitled ‘Getting tough on corporate irresponsibility’ referenced an unhealthy gap growing between the pay packets of workers and bosses of big business. -

Rosalind M. Altmann

DR. ROS ALTMANN email: [email protected] website: www.rosaltmann.com PROFILE • Independent adviser to Government and financial industry on pensions, savings and investment policy • Investment professional with 20 years’ investment experience • Wide range of investment expertise, including equity analysis, global equity strategy, asset allocation, venture capital and hedge fund strategy • Media expert and widely quoted commentator on investment and pensions policy • Non-Executive Director and a Governor of the London School of Economics CAREER DETAILS INVESTMENT STRATEGY/PENSIONS POLICY Independent Consultant 1993 - . Independent adviser, strategic consultant to investment companies on wide range of issues, including absolute return investing, managing both risk and returns, hedge fund strategy, asset allocation, venture capital and valuation of smaller companies. Also media commentator with extensive radio and TV experience on pensions, economics and financial issues. TRUSTEE TRAFALGAR HOUSE PENSION FUND 2007 - . Joined Trustee Board of £1.3billion Trafalgar House Pension Fund LORD CHANCELLOR’S STRATEGIC INVESTMENT BOARD 2004 - . Public appointment as Member of the Strategic Investment Board of the Lord Chancellor’s Office. Advising on investment matters for over £5.5 billion of assets for the Public Guardianship Office, Court Funds Office, Official Solicitor and other bodies. GOVERNMENT POLICY ADVISER 2000 to 2005 Policy adviser to Number 10 Policy Unit on wide range of pension policy issues, including policy proposals for pensions, lifetime savings and annuities. Devised policy initiatives to reform both state and private pensions, retirement policy and encourage middle income groups to save. CONSULTANT TO UK TREASURY Apr-Sep 2000 Consultant to UK Treasury and Paul Myners on the Myners Review of institutional investment. -

MA Thesis S2009803 International Relations Culture & Politics MA Thesis International Relations – Culture & Politics 1St Reader: Dr

Yannic Bode MA Thesis s2009803 International Relations Culture & Politics MA Thesis International Relations – Culture & Politics 1st Reader: Dr. Camilo Erlichman 2nd Reader: Dr. Maxine E. L. David Student: Yannic L. Bode Student Number: 2009803 Title: Sovereignty in the Brexit Debate: Competing Conceptions between Left- and Right-wing Newspapers Research Question: How do understandings of sovereignty differ between discourses in left- and right- wing newspapers in the UK during the runup to the Brexit referendum? Abstract: On June 23, 2016, a referendum in the UK made clear that the EU would lose a member for the first time since its birth in 1951. In a highly intense campaign during the months before the referendum, those in favor of Brexit faced off those that fought to maintain the status quo. Among the many issues debated, sovereignty emerged as heavily contested. This thesis attempts to shed some light on the competing concepts of sovereignty that were used by the two camps by analyzing the discourses of left- and right-wing newspapers in the UK. After performing a discourse analysis of 90 articles that these newspapers published during the runup to the referendum, this thesis concludes that right-wing newspapers view sovereignty as an indivisible, high-value concept that should be held by a national, democratically elected government. By contrast, left-wing newspapers view it as having various degrees, which makes them more willing to cede some of it, if this benefits the nation. Academically, the thesis draws on existing literature about sovereignty and the British understanding of it, expanding on this literature especially through the insights on the British left-wing newspapers’ discourse.