The Order:Ecumenical in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Railway Line to Broken Hill

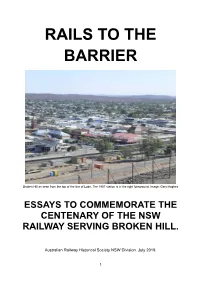

RAILS TO THE BARRIER Broken Hill as seen from the top of the line of Lode. The 1957 station is in the right foreground. Image: Gary Hughes ESSAYS TO COMMEMORATE THE CENTENARY OF THE NSW RAILWAY SERVING BROKEN HILL. Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. July 2019. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF BROKEN HILL......................................................................... 5 THE MINES................................................................................................ 7 PLACE NAMES........................................................................................... 9 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE....................................................................... 12 CULTURE IN THE BUILDINGS...................................................................... 20 THE 1919 BROKEN HILL STATION............................................................... 31 MT GIPPS STATION.................................................................................... 77 MENINDEE STATION.................................................................................. 85 THE 1957 BROKEN HILL STATION................................................................ 98 SULPHIDE STREET STATION........................................................................ 125 TARRAWINGEE TRAMWAY......................................................................... 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

Rose's LEGACY

Rose’s Legacy Contents 1967 ............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 EARLIER ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 SHARN ......................................................................................................................................................................... 13 TRAUMA ................................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1 ........................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 2 ........................................................................................................................................................................... 19 Chapter 3 ........................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Chapter 4 ........................................................................................................................................................................... 33 Chapter 5 .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

List-Of-All-Postcodes-In-Australia.Pdf

Postcodes An alphabetical list of postcodes throughout Australia September 2019 How to find a postcode Addressing your mail correctly To find a postcode simply locate the place name from the alphabetical listing in this With the use of high speed electronic mail processing equipment, it is most important booklet. that your mail is addressed clearly and neatly. This is why we ask you to use a standard format for addressing all your mail. Correct addressing is mandatory to receive bulk Some place names occur more than once in a state, and the nearest centre is shown mail discounts. after the town, in italics, as a guide. It is important that the “zones” on the envelope, as indicated below, are observed at Complete listings of the locations in this booklet are available from Australia Post’s all times. The complete delivery address should be positioned: website. This data is also available from state offices via the postcode enquiry service telephone number (see below). 1 at least 40mm from the top edge of the article Additional postal ranges have been allocated for Post Office Box installations, Large 2 at least 15mm from the bottom edge of the article Volume Receivers and other special uses such as competitions. These postcodes follow 3 at least 10mm from the left and right edges of the article. the same correct addressing guidelines as ordinary addresses. The postal ranges for each of the states and territories are now: 85mm New South Wales 1000–2599, 2620–2899, 2921–2999 Victoria 3000–3999, 8000–8999 Service zone Postage zone 1 Queensland -

Draft 15-Year Infrastructure Strategy

20082008----20242024 Interstate and Hunter Valley Rail Infrastructure Strategy 30 June 2008 1 1 Introduction Purpose of this Strategy some States took the view that their rail freight businesses Purpose of this Strategy would be best privatised as vertically integrated concerns. The primary purpose of this Strategy is to assist Infra- By the early 2000’s, all of the Government rail freight structure Australia with its audit of nationally significant operators had been privatised with the exception of the infrastructure by setting out ARTC’s expectations of poten- Queensland Government owned QR. In conjunction with tial growth on the interstate and Hunter Valley rail net- this process, rail freight had also been fully separated from works over the 2008 – 2024 period, and identifying the passenger services, again with the exception of QR. infrastructure that may need to be developed to avoid bottlenecks to volume growth, and remove bottlenecks to Through the mid-2000’s period, three of the rail freight efficiency. businesses that had been privatised as vertically inte- grated concerns became vertically separated, with the This first section of the Strategy provides a high level track reverting to Government control in two of these overview of the industry, ARTC and current investments. cases. As this evolution continues there is a reasonably clear The Structure of the Australian Railway pattern to the ownership and operation of the Australian Industry rail network developing as follows: • The interstate standard gauge network has been At the time of Federation, the State's rail systems had vertically separated and most of the network con- been developed as a series of stand-alone networks, radi- solidated under ARTC control, as discussed in the ating from the major ports to serve the hinterland and following section. -

Local Strategic Planning Statement

Cobar Shire LOCAL STRATEGIC PLAN NING STATEMENT A CKNOWLEDGMENT OF C OUNTRY We acknowledge and respect the traditional lands for all Aboriginal people, we respect all Elders past, present and future. We ask all people that walk, work and live on traditional Aboriginal lands, to be respectful of culture and traditions, we stand tog ether side by side, united with respect for land for oneself and for one another. WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are warned that this document may contain images of people who have died. COBAR LOCAL STRATEGI C PLANNING STATEMENT 1 1 F ORWARD Cobar Shire is situated in the centre of New South Wales at the crossroads of the Barrier Highway and the Kidman Way and has excellent road, rail and air links to most of Australia's capital cities. With an area of 45,609 square kilometres, the Shire is approximately two - thirds the size of Tasmania. It is home to approximately 4,647 people. The Shire's prosperity is built around the thriving mining - copper, lead, silver, zinc, gold - and pastoral industries, which are strongly supported by a wide range of attractions and activities, th at make it a major tourist destination. One of the most important jobs of Council is to set the strategic direction that guides our work to improve life in Cobar Shire. To assist with this, Council has prepared a Local Strategic Planning Statement . This S tatement is owned by the community of Cobar Shire. It is not a Council plan; however, Council has taken responsibility for bringing the plan together, overseeing its implementation and reporting back to the community on progress made. -

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects 1 COPYRIGHT DISCLAIMER Restart NSW Local and Community While every reasonable effort has been made Infrastructure Projects to ensure that this document is correct at the time of publication, Infrastructure NSW, its © July 2019 State of New South Wales agents and employees, disclaim any liability to through Infrastructure NSW any person in response of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to This document was prepared by Infrastructure be done in reliance upon the whole or any part NSW. It contains information, data and images of this document. Please also note that (‘material’) prepared by Infrastructure NSW. material may change without notice and you should use the current material from the The material is subject to copyright under Infrastructure NSW website and not rely the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), and is owned on material previously printed or stored by by the State of New South Wales through you. Infrastructure NSW. For enquiries please contact [email protected] This material may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial Front cover image: Armidale Regional use, providing the meaning is unchanged and Airport, Regional Tourism Infrastructure its source, publisher and authorship are clearly Fund and correctly acknowledged. 2 Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects The Restart NSW Fund was established by This booklet reports on local and community the NSW Government in 2011 to improve infrastructure projects in regional NSW, the economic growth and productivity of Newcastle and Wollongong. The majority of the state. -

VISITOR MAP Central West New South Wales

PAD-MAP-REGIONAL.pdf 1 18/10/2016 8:41:16 AM A B C D E F G H B87 B71 CASTLEREAGH VISITOR MAP Miners Memorial B55 BRISBANE via BARRIER HIGHWAY A39 Newell Hwy & HIGHWAY Goondiwindi A32 Cobar BARRIER HIGHWAY 750 km Fort Bourke Boppy A32 Nyngan Biddon Central West Hill Lookout Mountain Canbelego Hermidale ADELAIDE A39 1 via A32 Barrier Hwy Nyngan MITCHELL HWY & Broken Hill New South Wales 928 km Centenary GILGANDRA Fountain WARREN OXLEY HWY NEWELL Collie HIGHWAY ° B87 Mt Nurri Warren M a c q u a r i e Gilgandra B55 N A32 R i v e r SYDNEY via B55 0 25km Castlereagh Hwy & Mudgee Nevertire 418 km Bald Kidman Way Hill INDEX OF PLACE NAMES Albert E3 Peak Hill G4 Buckambool Alectown G5 Rankins Springs C7 Mountain Mt Surprise Bena E6 Roto A5 Eumungerie Biddon H1 Tabratong E3 2 BOGAN Bobadah C3 Tallimba D7 Bogan Gate F5 Tomingley G4 A39 Bumbaldry G7 Toogong H6 Nymagee Trangie MITCHELL HWY Burcher E6 Tottenham E3 Mogriguy Bygalorie D6 Trangie F2 Calarie G6 Trundle F5 Canbelego C1 Tullamore E4 The Bogan Way Five Ways Canowindra H6 Tullibigeal D6 Geographical T a l b r a g a r Caragabal F7 Ungarie D7 Tabratong Cave Cargo H6 Warren F1 centre of NSW R i v e r Hill Cobar A1 Warroo F6 A32 NEWCASTLE via Collie G1 Weethalle C7 cairn B o g a n B84 B84 Golden Hwy & Dunedoo Condobolin E5 Weja D6 COBAR Tottenham Narromine GOLDEN 358 km Cookamidgera G5 West Wyalong E7 DUBBO HWY Cowra H7 Woodstock H7 Dandaloo Cudal H6 Wyalong E7 Bobadah NARROMINE Taronga Western DUBBMITCHELLO Cumnock H5 Yarrabandai F5 Plains Zoo A32 Curlew Waters C6 Yeoval H4 The Bogan HWY Dandaloo -

Suburb Postcode State Zone Port Code Acton 2601 Act 32

SUBURB POSTCODE STATE ZONE PORT CODE ACTON 2601 ACT 32 ACT AINSLIE 2602 ACT 32 ACT AMAROO 2914 ACT 32 ACT ARANDA 2614 ACT 32 ACT AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL 2600 ACT 32 ACT BANKS 2906 ACT 32 ACT BARKER CENTRE 2603 ACT 32 ACT BARTON 2600 ACT 32 ACT BELCONNEN 2617 ACT 32 ACT BIMBERI 2611 ACT 32 ACT BLACK MOUNTAIN 2601 ACT 32 ACT BONNER 2914 ACT 32 ACT BONYTHON 2905 ACT 32 ACT BOOROOMBA 2620 ACT 32 ACT BRADDON 2612 ACT 32 ACT BRINDABELLA 2611 ACT 32 ACT BRUCE 2617 ACT 32 ACT BURBONG 2620 ACT 32 ACT BURRA 2620 ACT 32 ACT SUBURB POSTCODE STATE ZONE PORT CODE BURRA CREEK 2620 ACT 32 ACT CALWELL 2905 ACT 32 ACT CAMPBELL 2612 ACT 32 ACT CANBERRA 2600 ACT 32 ACT CANBERRA 2600 ACT 32 ACT CANBERRA DEPOT 2911 ACT 32 ACT CAPITAL HILL 2600 ACT 32 ACT CARWOOLA 2620 ACT 32 ACT CASEY 2913 ACT 32 ACT CASUARINA SANDS 2611 ACT 32 ACT CAUSEWAY 2604 ACT 32 ACT CHAPMAN 2611 ACT 32 ACT CHARNWOOD 2615 ACT 32 ACT CHIFLEY 2606 ACT 32 ACT CHISHOLM 2905 ACT 32 ACT CIVIC 2608 ACT 32 ACT CIVIC SQUARE 2608 ACT 32 ACT CLEAR RANGE 2620 ACT 32 ACT CONDER 2906 ACT 32 ACT SUBURB POSTCODE STATE ZONE PORT CODE COOK 2614 ACT 32 ACT COOLEMAN 2611 ACT 32 ACT COOMBS 2611 ACT 32 CORIN DAM 2620 ACT 32 ACT COTTER RIVER 2611 ACT 32 ACT CRACE 2911 ACT 32 ACT CRESTWOOD 2620 ACT 32 ACT CUPPACUMBALONG 2620 ACT 32 ACT CURTIN 2605 ACT 32 ACT DEAKIN 2600 ACT 32 ACT DEAKIN WEST 2600 ACT 32 ACT DICKSON 2602 ACT 32 ACT DODSWORTH 2620 ACT 32 ACT DOWNER 2602 ACT 32 ACT DUFFY 2611 ACT 32 ACT DUNLOP 2615 ACT 32 ACT DUNTROON 2600 ACT 32 ACT ENVIRONA 2620 ACT 32 ACT ERINDALE CENTRE 2903 ACT 32 ACT SUBURB -

A Lower Lachlan Survey

• Pastoralism and the Landscape: A lower Lachlan Survey Anne 0 'Kane Cannon A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Department of Prehistory and Historical Archaeology The University of Sydney 1992 Volume II N.T. QL·D W.A.: - ~ ·~A . ·- - -S ~ 1-\. - -- ------. ·-· .... .•.t__...- ... ,_ N.S.W. ·, 4 ~Vic. Tas. # ___ ......_~·- ._ -~eJ·Y - SOU .TH .. ... ~~~ WALES -·· - . .... ·--·- Lake Cargelhoo • .... ..... Sydney ACT 200km Fig. Al: Map of New South Wales showing the location of the lower Lachlan area. Al (/) ~ 1:! ..... 1-.t()q ~ . ~. l'V~ LEGEND ~ 0 Wkm .. l46°E I I Maio Road ~~ Sto t:s"'d StJ:uvation Tanlc • • • • • • Railway 'woolslud o D s ~ 0 Town <b e-t ''Coan Downs" • C/) t::r ... 0 ('1) MtAI/en • Homestead ~ en 518m "o "" ~ g_ Mount Hope 0c-t-~ ~~('1) (/) ~ c-t- ....~~. 0 g ~ • (/) .... t:SooDero1 t:s > ~Oq t-.:) <b ..._ 0 ..... (') Roto ,oonthumble" ,-IlL t:s ~ • v:.. "Brotherony" ..0 c-t- 1:! .... Euabalong-- 0 g C"t- "-.."V / ~ 0 "North Whoey" " rt "Euabalong" ~~ O"o "Hyandra" b ...., "Uab)~b:a_:",_G,_': ~,)) s ~ • o "Wooveo wools/red" ~ ~ ~ ~. C/) ('1) . (/) •unthawang"-~ ("') :lP 4 g \ en ..... ........,..._......,,_Tullbigeal Q. ~"',._N • "Willan~~J;Yw ~ ,..o "Merri Merrigal" ' ~ Cb ',~ ! Q. ~ .... .... " Lake Brewster 5 ::s HILLSTON ::rc-t- 1 ('1) ~~ UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY C•rtogr•phy f VAilAlONG 21 ~ ... "'V II~ I N llii•CGE ()l.m CAitG{WGO wtl• 10."' , # .4 0 4 l 42 J3 44 -1 5 46 n 9 ,. N••df•s • 14 J5 / Swamp 68 67 \.- c , •~i i •• 66 . -

Derailment of Train 7SP3, Roto, NSW, 4 March 2012

DerailmentInsert document of train 7SP3title LocationRoto, New | Date South Wales | 4 March 2012 ATSB Transport Safety Report Investigation [InsertRail Occurrence Mode] Occurrence Investigation Investigation XX-YYYY-####RO-2012-002 Final – 30 August 2013 Cover photo: Source ATSB Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 (24 hours) Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. -

GSR Indian Pacific

GREAT SOUTHERN RAIL INTERSTATE TRAINS Reservations are necessary on all Great Southern services GS1 SYDNEY - ADELAIDE - PERTH "INDIAN PACIFIC" The great transcontinental trip, including crossing the Blue Mountains, the Nullarbor Plain (478 km without a curve) and the Darling Ranges. Jn19 SG. Parallel to BG Adelaide-Salisbury. Sextuple track Sydney-Homebush, Quadruple track Homebush-St Marys, Double track St Marys-Wallerawang, Tarana-Kelso, Newbridge-Murrobo, Spring Hill - Orange East Fork Jnc., Crystal Brook-Coonamia. Double track & Dual Gauge Northam-Perth. Electrified for EMUs Sydney-Lithgow and Midland-Perth. The Indian Pacific reverses in Adelaide and retraces its route to Crystal Brook. For line description and detailed times Sydney-Orange Fork Jnc see Table NC3. For all trains between Sydney-Penrith see Table NM4, Penrith-Lithgow NI13, Lithgow-Orange NC3. For all trains between Adelaide and Tarcoola see Table GS2. For all trains between Kalgoorlie and Perth see Table WC1. Operators: Great Southern Rail (Indian Pacific) & NSW Train Link (Broken Hill train). INDIAN PACIFIC SUMMARY TIMETABLE - ADVERTISED PUBLIC TIMETABLE ALL YEAR SYDNEY dep 1500 WED BROKEN HILL arr 600 THUR dep 820 THUR Off-train excursions available in ADELAIDE arr 1515 THUR Broken Hill, Adelaide, Rawlinna. dep 2140 THUR COOK arr 1330 FRI dep 1310 FRI RAWLINNA arr 1755 FRI dep 2035 FRI KALGOORLIE arr 305 SAT dep ? SAT PERTH arr 1457 SAT ALL YEAR PERTH dep 1000 SUN KALGOORLIE arr 2050 SUN Off-train excursions available in Kalgoorlie, Rawlinna, dep 120 MON Adelaide, -

Government Gazette

483 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 13 Friday, 27 January 2006 Published under authority by Government Advertising and Information LEGISLATION Proclamations New South Wales Proclamation under the Security Interests in Goods Act 2005 No 69 MARIE BASHIR,, GovernorGovernor I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 2 of the Security Interests in Goods Act 2005, do, by this my Proclamation, appoint 1 March 2006 as the day on which that Act commences. SignedSigned and sealedsealed at at Sydney, Sydney, this this 25th day ofday January of 2006. 2006. By Her Excellency’s Command, ANTHONY KELLY, M.L.C., L.S. MinisterMinister forfor Lands GOD SAVE THE QUEEN! s05-673-94.p01 Page 1 484 LEGISLATION 27 January 2006 Regulations New South Wales Conveyancing (General) Amendment Regulation 2006 under the Conveyancing Act 1919 Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Conveyancing Act 1919. ANTHONY KELLY, M.L.C., MinisterMinister forfor Lands Lands Explanatory note The object of this Regulation is to amend the Conveyancing (General) Regulation 2003 to ensure that fees for the registration of security instruments under the Security Interests in Goods Act 2005 or memoranda of covenants for such instruments reflect the fees payable for the registration of comparable instruments immediately before the commencement of the Security Interests in Goods Act 2005. This Regulation is made under the Conveyancing Act 1919, including section 202 (General rules under this Part as to registration and fees).