Introduction to Animal Evolution Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cleavage of Cytoskeletal Proteins by Caspases During Ovarian Cell Death: Evidence That Cell-Free Systems Do Not Always Mimic Apoptotic Events in Intact Cells

Cell Death and Differentiation (1997) 4, 707 ± 712 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 13509047/97 $12.00 Cleavage of cytoskeletal proteins by caspases during ovarian cell death: evidence that cell-free systems do not always mimic apoptotic events in intact cells Daniel V. Maravei1, Alexander M. Trbovich1, Gloria I. Perez1, versus the cell-free extract assays (actin cleaved) raises Kim I. Tilly1, David Banach2, Robert V. Talanian2, concern over previous conclusions drawn related to the Winnie W. Wong2 and Jonathan L. Tilly1,3 role of actin cleavage in apoptosis. 1 The Vincent Center for Reproductive Biology, Department of Obstetrics and Keywords: apoptosis; caspase; ICE; CPP32; actin; fodrin; Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, proteolysis; granulosa cell; follicle; atresia Boston, Massachusetts 02114 USA 2 Department of Biochemistry, BASF Bioresearch Corporation, Worcester, Massachusetts 01605 USA Abbreviations: caspase, cysteine aspartic acid-speci®c 3 corresponding author: Jonathan L. Tilly, Ph.D., Massachusetts General protease (CASP, designation of the gene); ICE, interleukin- Hospital, VBK137E-GYN, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, Massachusetts 1b-converting enzyme; zVAD-FMK, benzyloxycarbonyl-Val- 02114-2696 USA. tel: +617 724 2182; fax: +617 726 7548; Ala-Asp-¯uoromethylketone; zDEVD-FMK, benzyloxycarbo- e-mail: [email protected] nyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-¯uoromethylketone; kDa, kilodaltons; Received 28.1.97; revised 24.4.97; accepted 14.7.97 ICH-1, ICE/CED-3 homolog-1; CPP32, cysteine protease Edited by J.C. Reed p32; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose)-polymerase; MW, molecular weight; STSP, staurosporine; C8-CER, C8-ceramide; DTT, dithiothrietol; cCG, equine chorionic gonadotropin (PMSG or Abstract pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin); ddATP, dideoxy-ATP; kb, kilobases; HEPES, N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N'-(2- Several lines of evidence support a role for protease ethanesulfonic acid); SDS ± PAGE, sodium dodecylsulfate- activation during apoptosis. -

The NEURONS and NEURAL SYSTEM: a 21St CENTURY PARADIGM

The NEURONS and NEURAL SYSTEM: a 21st CENTURY PARADIGM This material is excerpted from the full β-version of the text. The final printed version will be more concise due to further editing and economical constraints. A Table of Contents and an index are located at the end of this paper. A few citations have yet to be defined and are indicated by “xxx.” James T. Fulton Neural Concepts [email protected] July 19, 2015 Copyright 2011 James T. Fulton 2 Neurons & the Nervous System 4 The Architectures of Neural Systems1 [xxx review cogn computation paper and incorporate into this chapter ] [xxx expand section 4.4.4 as a key area of importance ] [xxx Text and semantics needs a lot of work ] Don’t believe everything you think. Anonymous bumper sticker You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool Richard Feynman I am never content until I have constructed a model of what I am studying. If I succeed in making one, I understand; otherwise, I do not. William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) It is the models that tell us whether we understand a process and where the uncertainties remain. Bridgeman, 2000 4.1 Background [xxx chapter is a hodge-podge at this time 29 Aug 11 ] The animal kingdom shares a common neurological architecture that is ramified in a specific species in accordance with its station in the phylogenic tree and the ecological domain. This ramification includes not only replication of existing features but further augmentation of the system using new and/or modified features. -

Vertebrate Embryonic Cleavage Pattern Determination

Chapter 4 Vertebrate Embryonic Cleavage Pattern Determination Andrew Hasley, Shawn Chavez, Michael Danilchik, Martin Wühr, and Francisco Pelegri Abstract The pattern of the earliest cell divisions in a vertebrate embryo lays the groundwork for later developmental events such as gastrulation, organogenesis, and overall body plan establishment. Understanding these early cleavage patterns and the mechanisms that create them is thus crucial for the study of vertebrate develop- ment. This chapter describes the early cleavage stages for species representing ray- finned fish, amphibians, birds, reptiles, mammals, and proto-vertebrate ascidians and summarizes current understanding of the mechanisms that govern these pat- terns. The nearly universal influence of cell shape on orientation and positioning of spindles and cleavage furrows and the mechanisms that mediate this influence are discussed. We discuss in particular models of aster and spindle centering and orien- tation in large embryonic blastomeres that rely on asymmetric internal pulling forces generated by the cleavage furrow for the previous cell cycle. Also explored are mechanisms that integrate cell division given the limited supply of cellular building blocks in the egg and several-fold changes of cell size during early devel- opment, as well as cytoskeletal specializations specific to early blastomeres A. Hasley • F. Pelegri (*) Laboratory of Genetics, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Genetics/Biotech Addition, Room 2424, 425-G Henry Mall, Madison, WI 53706, USA e-mail: [email protected] S. Chavez Division of Reproductive & Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Department of Physiology & Pharmacology, Oregon Heath & Science University, 505 NW 185th Avenue, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA Division of Reproductive & Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Oregon Heath & Science University, 505 NW 185th Avenue, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA M. -

S I Section 4

3/31/2011 Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Porifera Ecdysozoa Deuterostomia Lophotrochozoa Cnidaria and Ctenophora Cnidaria and Protostomia SSiection 4 Radiata Bilateria Professor Donald McFarlane Parazoa Eumetazoa Lecture 13 Invertebrates: Parazoa, Radiata, and Lophotrochozoa Ancestral colonial choanoflagellate 2 Traditional classification based on Parazoa – Phylum Porifera body plans Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Parazoa 4 main morphological and developmental Sponges features used Loosely organized and lack Porifera Ecdysozoa Cnidaria and Ctenophora tissues euterostomia photrochozoa D 1. o Presence or absence of different tissue L Multicellular with several types of types Protostomia cells 2. Type of body symmetry Radiata Bilateria 8,000 species, mostly marine Parazoa Eumetazoa 3. Presence or absence of a true body No apparent symmetry cavity Ancestral colonial Adults sessile, larvae free- choanoflagellate 4. Patterns of embryonic development swimming 3 4 1 3/31/2011 Water drawn through pores (ostia) into spongocoel Flows out through osculum Reproduce Choanocytes line spongocoel Sexually Most hermapppgggphrodites producing eggs and sperm Trap and eat small particles and plankton Gametes are derived from amoebocytes or Mesohyl between choanocytes and choanocytes epithelial cells Asexually Amoebocytes absorb food from choanocytes, Small fragment or bud may detach and form a new digest it, and carry -

Animal Diversity Part 2

Textbook resources • pp. 517-522 • pp. 527-8 Animal Diversity • p. 530 part 2 • pp. 531-2 Clicker question In protostomes A. The blastopore becomes the mouth. B. The blastopore becomes the anus. C. Development involves indeterminate cleavage. D. B and C Fig. 25.2 Phylogeny to know (1). Symmetry Critical innovations to insert: Oral bilateral symmetry ecdysis mouth develops after anus multicellularity Aboral tissues 1 Animal diversity, part 2 Parazoa Diversity 2 I. Parazoa • Porifera: Sponges II. Cnidaria & Ctenophora • Tissues • Symmetry I. Outline the • Germ Layers III. Lophotrochozoa unique • Embryonic characteristics Development of sponges IV. Ecdysozoa • Body Cavities • Segmentation Parazoa Parazoa • Porifera: Sponges • Porifera: Sponges – Multicellular without – Hermaphrodites tissues – Sexual and asexual reproduction – Choanocytes (collar cells) use flagella to move water and nutrients into pores – Intracellular digestion Fig. 25.11 Animal diversity, part 2 Clicker Question Diversity 2 I. Parazoa In diploblastic animals, the inner lining of the digestive cavity or tract is derived from II. Cnidaria & Ctenophora A. Endoderm. II. Outline the B. Ectoderm. unique III. Lophotrochozoa C. Mesoderm. characteristics D. Coelom. of cnidarians and IV. Ecdysozoa ctenophores 2 Coral Box jelly Cnidaria and Ctenophora • Cnidarians – Coral; sea anemone; jellyfish; hydra; box jellies • Ctenophores – Comb jellies Sea anemone Jellyfish Hydra Comb jelly Cnidaria and Ctenophora Fig. 25.12 Coral Box jelly Cnidaria and Ctenophora • Tissues Fig. 25.12 – -

Cleavage: Types and Patterns Fertilization …………..Cleavage

Cleavage: Types and Patterns Fertilization …………..Cleavage • The transition from fertilization to cleavage is caused by the activation of mitosis promoting factor (MPF). Cleavage • Cleavage, a series of mitotic divisions whereby the enormous volume of egg cytoplasm is divided into numerous smaller, nucleated cells. • These cleavage-stage cells are called blastomeres. • In most species the rate of cell division and the placement of the blastomeres with respect to one another is completely under the control of the proteins and mRNAs stored in the oocyte by the mother. • During cleavage, however, cytoplasmic volume does not increase. Rather, the enormous volume of zygote cytoplasm is divided into increasingly smaller cells. • One consequence of this rapid cell division is that the ratio of cytoplasmic to nuclear volume gets increasingly smaller as cleavage progresses. • This decrease in the cytoplasmic to nuclear volume ratio is crucial in timing the activation of certain genes. • For example, in the frog Xenopus laevis, transcription of new messages is not activated until after 12 divisions. At that time, the rate of cleavage decreases, the blastomeres become motile, and nuclear genes begin to be transcribed. This stage is called the mid- blastula transition. • Thus, cleavage begins soon after fertilization and ends shortly after the stage when the embryo achieves a new balance between nucleus and cytoplasm. Cleavage Embryonic development Cleavage 2 • Division of first cell to many within ball of same volume (morula) is followed by hollowing -

BIOL 2290 - 3 EVOLUTION of ANIMAL BODY PLANS (3,0,3) Winter 2020

BIOL 2290 - 3 EVOLUTION OF ANIMAL BODY PLANS (3,0,3) Winter 2020 Instructor: Dr. Louis Gosselin Office: Research Centre RC203 Email: [email protected] Course website: www.faculty.tru.ca/lgosselin/biol2290/ Meeting times Lectures: Mon 8:30 - 9:45 [AE 162] Wed 8:30 - 9:45 [AE 162] Laboratories - 3 hours per week [S 378] Calendar description This course explores the spectacular diversity of animal body plans, and examines the sequence of events that lead to this diversity. Lectures and laboratories emphasize the inherent link between body form, function and phylogeny. The course also highlights the diverse roles that animals play in natural ecosystems as well as their implications for humans, and examines how knowledge of animal morphology, development, and molecular biology allows us to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree of the Animalia. Educational objectives Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to identify the major evolutionary events that lead to the current diversity of animal body plans, and the selective pressures that favoured each type of body plan. They will be able to recognize the functional significance of animal body design, relating morphology with specific lifestyles. Students will be able to describe the major functions that animals play in natural ecosystems and the significance of different animals for humans. In addition, students successfully completing the laboratory component of the course will be skilled in dissection techniques, identification, and in the basic design, execution and analysis of a scientific experiment with animals. Prerequisites BIOL1110, BIOL1210 Required texts Ruppert EE, Fox RS, Barnes RD (2004) Invertebrate Zoology. -

FISH310: Biology of Shellfishes

FISH310: Biology of Shellfishes Lecture Slides #3 Phylogeny and Taxonomy sorting organisms How do we classify animals? Taxonomy: naming Systematics: working out relationships among organisms Classification • All classification schemes are, in part, artificial to impose order (need to start some where using some information) – Cell number: • Acellular, One cell (_________), or More than one cell (metazoa) – Metazoa: multicellular, usu 2N, develop from blastula – Body Symmetry – Developmental Pattern (Embryology) – Evolutionary Relationship Animal Kingdom Eumetazoa: true animals Corals Anemones Parazoa: no tissues Body Symmetry • Radial symmetry • Phyla Cnidaria and Ctenophora • Known as Radiata • Any cut through center ! 2 ~ “mirror” pieces • Bilateral symmetry • Other phyla • Bilateria • Cut longitudinally to achieve mirror halves • Dorsal and ventral sides • Anterior and posterior ends • Cephalization and central nervous system • Left and right sides • Asymmetry uncommon (Porifera) Form and Life Style • The symmetry of an animal generally fits its lifestyle • Sessile or planktonic organisms often have radial symmetry • Highest survival when meet the environment equally well from all sides • Actively moving animals have bilateral symmetry • Head end is usually first to encounter food, danger, and other stimuli Developmental Pattern • Metazoa divided into two groups based on number of germ layers formed during embryogenesis – differs between radiata and bilateria • Diploblastic • Triploblastic Developmental Pattern.. • Radiata are diploblastic: two germ layers • Ectoderm, becomes the outer covering and, in some phyla, the central nervous system • Endoderm lines the developing digestive tube, or archenteron, becomes the lining of the digestive tract and organs derived from it, such as the liver and lungs of vertebrates Diploblastic http://faculty.mccfl.edu/rizkf/OCE1001/Images/cnidaria1.jpg Developmental Pattern…. -

Lineage and Fate of Each Blastomere of the Eight-Cell Sea Urchin Embryo

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Lineage and fate of each blastomere of the eight-cell sea urchin embryo R. Andrew Cameron, Barbara R. Hough-Evans, Roy J. Britten, ~ and Eric H. Davidson Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125 USA A fluoresceinated lineage tracer was injected into individual blastomeres of eight-cell sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) embryos, and the location of the progeny of each blastomere was determined in the fully developed pluteus. Each blastomere gives rise to a unique portion of the advanced embryo. We confirm many of the classical assignments of cell fate along the animal-vegetal axis of the cleavage-stage embryo, and demonstrate that one blastomere of the animal quartet at the eight-cell stage lies nearest the future oral pole and the opposite one nearest the future aboral pole of the embryo. Clones of cells deriving from ectodermal founder cells always remain contiguous, while clones of cells descendant from the vegetal plate {i.e., gut, secondary mesenchyme) do not. The locations of ectodermal clones contributed by specific blastomeres require that the larval plane of bilateral symmetry lie approximately equidistant {i.e., at a 45 ° angle) from each of the first two cleavage planes. These results underscore the conclusion that many of the early spatial pattems of differential gene expression observed at the molecular level are specified in a clonal manner early in embryonic sea urchin development, and are each confined to cell lineages established during cleavage. [Key Words: Development; cell lineage; dye injection; axis specification] Received December 8, 1986; accepted December 24, 1986. -

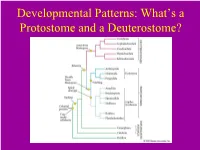

Developmental Patterns: What's a Protostome and a Deuterostome?

Developmental Patterns: What’s a Protostome and a Deuterostome? Early Development cleavage • Fertilized Egg Blastula reorganization • Blastula Gastrula What Characterizes Cleavage? • Outcome – large egg divided into typical small cells – large increase in number of cells, chromatin, surface membrane • Characteristics – no growth – cell cycle: rapid S, little G1 – shape the same except for cavity (blastocoele) – use of storage reserves (from oogenesis) – embryonic gene activity relatively unimportant Cleavage Patterns I • Holoblastic – complete cleavage • Isolecithal – evenly distributed yolk • Mesolecithal – slight polarization of yolk Cleavage Patterns II • Meroblastic – incomplete division • Telolecithal – more yolk at one end • Centrolecithal – yolk in the center What Characterizes Gastrulation? • Outcome – increase in overt differentiation – morphogenetic changes • Characteristics – slowing of cell division – little if any growth – increasing importance of embryo gene activity – cell movements and rearrangements – establishment of basic body plan In What Ways Do Cells Move? Gastrulation • Common Processes – changes in cell contacts – motility – shape – cell-cell communication – interactions of cells with extracellular matrix – all precise and orderly The Body Plan • Gastrula establishes basic pattern – ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm – primary germ layers primordial organ rudiments – germ layers bring cells to new positions to • self-differentiate in correct spatial relationships • be induced by new neighbors Early Development of Selected -

How Cnidaria Got Its Cnidocysts

tems: ys Op l S e a n A ic c g c o l e s o i s Shostak, Biol syst Open Access 2015, 4:2 B Biological Systems: Open Access DOI: 10.4172/2329-6577.1000139 ISSN: 2329-6577 Review Article Open Access How Cnidaria Got Its Cnidocysts Stanley Shostak* Department of Biological Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, USA *Corresponding author: Stanley Shostak, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, USA, Tel: 0114129156595, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: May 06, 2015; Accepted date: Aug 03, 2015; Published date: Aug 11, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Shostak S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract A complex hypothesis is offered for the origins of cnidarian cnidocysts through symbiogeny. The two-part hypothetical pathway links the origins of tissues through an early amalgamation of amoebic and epithelial cells to and the later introduction of an extrusion apparatus from bacterial parasites. The first part of the hypothesis is based on evidence for morphological, molecular, and developmental similarities of cnidarians and myxozoans indicative of common ancestry. Support is drawn from Ediacaran fossils suggesting that stem-metazoans consisted of symbiogenic pairs of epithelial-like shells enclosing amoeba-like cells. The amoeba-like cells would have evolved into germ cells and cells differentiating as or inducing nerve, muscle, and gland cells. The second part of the hypothesis proposes that cnidocysts evolved in a cnidarian/myxozoan branch of the metazoan tree through the horizontal transfer of bacterial genes encoding an extrusion apparatus to proto-cnidarian amoebic cells and consequently to the Cnidarian germ line. -

Cambrian Explosion: the Evolution the Evolution of Animal Body

Cambrian Explosion: The Evolution of Animal Body Plans I. What is a body plan? II. Cambrian Explosion III. Why have no new plans evolved? What is a body plan? (bauplan) At the upper levels of the taxonomic hierarchy, ppyhyla- or class-level clades are characterized by their possession of particular assemblages of homologous architectural and structural features… --J.J. W. Valentine (1986) Characteristics of Body Plans • Symmetry ••SkeletonSkeleton • Body Cavity • Segmentation • Appendages 1 Traditional Phylogeny Four Major Splits: 1) Parazoa-Eumetazoa 2) Radiata-Bilateria 3) Acoelomates-Coelomates 4) Protostomes-Deuterostomes Split 1: Several characters define Eumetazoa. • Tissues separated by basement membranes • Special Cell Junctions (other than septate junctions) • Neurons and Synapses • Muscle Split 2: Body symmetry defines Bilateria. 2 Two Phyla compose the Radiata. Ctenophora Cnidaria Bilateria are worms. Split 3: The presence of a body cavity defines Coelomates. 3 2 cells 4 cells morula blastula Split 4: Developmental characters define Deuterostomes. Traditional Phylogeny Four Major Splits: 1) Parazoa-Eumetazoa 2) Radiata-Bilateria 3) Acoelomates-Coelomates 4) Protostomes-Deuterostomes 4 Burgess Shale 540 mya Cambrian Sponges Cambrian Annelids 5 Cambrian Arthropods Cambrian Brachiopod Cambrian Chordate 6 Traditional Phylogeny Four Major Splits: 1) Parazoa-Eumetazoa 2) Radiata-Bilateria 3) Acoelomates-Coelomates 4) Protostomes-Deuterostomes Simon Conway Morris Opabinia Wiwaxia Hallucigenia 1. What selective factors caused the Cambrian Explosion? 2. Why have no new body plans evolved since? 7 What was so special about the Cambrian? • abiotic environment Atmospheric oxygen was fairly stable during the Cambrian. Cambrian Morris (1995) At the beginning of the Cambrian period, sea level was very similar to that of present day.