The Development of Single-Faith Broadcasting in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-688

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-688 PDF version Route reference: 2012-475 Ottawa, 19 December 2012 Touch Canada Broadcasting (2006) Inc. (the general partner) and C.R.A. Investments Ltd. (the limited partner), carrying on business as Touch Canada Broadcasting Limited Partnership Edmonton, Calgary and Red Deer, Alberta Application 2012-0642-5, received 24 May 2012 Public hearing in the National Capital Region 7 November 2012 CJCA and CJRY-FM Edmonton, CJLI and CJSI-FM Calgary and CKRD-FM Red Deer – Acquisition of assets (corporate reorganization) 1. The Commission approves the application by Touch Canada Broadcasting (2006) Inc. (the general partner) and C.R.A. Investments Ltd. (the limited partner), carrying on business as Touch Canada Broadcasting Limited Partnership (Touch Canada LP), for authorization to effect a two-step corporate reorganization involving the assets of the radio programming undertakings CJCA and CJRY-FM Edmonton, CJLI and CJSI-FM Calgary and CKRD-FM Red Deer. 2. Touch Canada Broadcasting (2006) Inc. and C.R.A. Investments Ltd. (CRA) are both controlled by Charles R. Allard. 3. The Commission did not receive any interventions in connection with this application. 4. The proposed corporate reorganization will be executed as follows: Step 1 • Transfer to CRA of all Class A voting shares issued by Touch Canada Broadcasting Inc. (TCBI), the current limited partner in Touch Canada LP and a corporation also owned and controlled by Mr. Allard. As a result, TCBI will become wholly owned by CRA. Step 2 • Wind up of TCBI. The 99.89% voting units held by TCBI in Touch Canada LP will be transferred to CRA. -

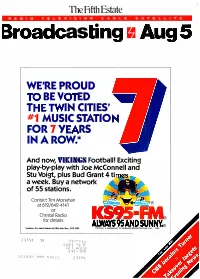

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

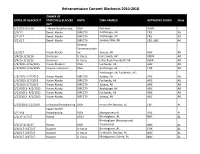

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Channel Line-Up VIP Digital Cable (Markham)

Channel Line-Up VIP Digital Cable (Markham) Here are the channels included in your package CH# INCL CH# INCL CH# INCL Your World This Week 1 Sportsnet 360 44 DIY Network 89 TV Ontario (TVO - CICA) 2 OLN 45 Disney Junior 92 Global Toronto (CIII) 3 Turner Classic Movies 46 Disney Channel 93 OMNI.1 4 TELETOON (East) 47 Free Preview Channel 1 94 TV Listings 5 Family Channel (East) 48 FX 95 CBC Toronto (CBLT) 6 Peachtree TV 49 NBA TV Canada 96 Citytv Toronto 7 CTV Comedy Channel (East) 50 Leafs Nation Network 97 CTV Toronto (CTVTO) 8 FX 51 TSN2 98 YES TV 9 Food Network 52 Sportsnet ONE 99 CHCH 11 ABC Spark 53 Rogers On Demand 100 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (TOR) 12 History 54 TVA Montreal (CFTM) 101 TFO (CHLF) 13 CTV Sci-Fi Channel 55 ICI RDI 102 OMNI.2 14 MTV 56 TV5 103 FX 15 BET (Black Entertainment 57 CPAC English (& CPAC French- 104 CBS Bufalo (WIVB) 16 DTOUR 58 Ontario Legislature 105 Sportsnet ONE 17 Your World This Week 59 Makeful 106 ABC Bufalo (WKBW) 18 VisionTV 60 A.Side 107 Today's Shopping Choice 19 PBS Bufalo (WNED) 61 CTV Toronto (CTVTO) 108 CTV Two Toronto 20 CTV News Channel 62 CTV Kitchener/London (CTVSO) 109 FOX Bufalo (WUTV) 21 Free Preview Channel 1 63 CTV Winnipeg (CTVWN) 110 The Weather Network (Richmond) 22 CTV Life Channel 64 CTV Calgary (CTVCA) 111 CBC News Network/AMI-audio 23 Treehouse 65 CTV Vancouver (CTVBC) 112 CP24 24 BNN Bloomberg 66 CTV Two Atlantic 113 YTV (East) 25 Nat Geo Wild 67 CTV Atlantic Halifax (CJCH) 114 TSN4 26 Family Jr. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

CHARLES TEMPLETON AND THE PERFORMANCES OF UNBELIEF by DAVID VANCE, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario August 12,2008 © Copyright 2008, David Vance Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43500-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43500-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

20-0607-1426 PD E (Pdf)

CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL NATIONAL SPECIALTY SERVICES PANEL VisionTV re Dil Dil Pakistan (CBSC Decision 06/07-1426) Decided November 29, 2007 R. Cohen (Chair), T. Rajan (Vice-Chair), E. Duffy-MacLean, M. Hogarth, V. Houle, G. Phelan THE FACTS VisionTV is a multi-faith and multi-cultural specialty service whose broadcasts are of one of two kinds; they are either Cornerstone programming (programming of various types produced by VisionTV or licensed by VisionTV from independent producers and distributors, including drama, documentaries, sitcoms, music programs, and lifestyle series) or Mosaic programming (programming provided to VisionTV by various faith groups that have either produced or acquired that programming and purchase time on VisionTV to broadcast it, the programming often being in the form of sermons, readings from scripture, talk shows, or short form documentaries). Dil Dil Pakistan was, at material times, a weekly English-language religious program of the Mosaic variety that included Arabic-language elements in its broadcasts. The foregoing being said, it should be noted that VisionTV is responsible for the broadcast content of both Cornerstone and Mosaic programming in the same way that any broadcaster is responsible for every moment of content it broadcasts. The Challenged Episodes On the July 14, 2007 episode, which aired from 3:00 pm to 4:00 pm, VisionTV broadcast an imam named Israr Ahmad giving a lesson or sermon that dealt with Sura 2 of the Qur’an, which is entitled Al-Baqara (it appears, from the Islamic, or Hijri, calendar year provided by the imam during the broadcast, namely, 1421, that the lesson was originally recorded, and possibly broadcast, in 2000, being the approximately equivalent Gregorian calendar year). -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

Core 1..120 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 148 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, October 26, 2016 Speaker: The Honourable Geoff Regan CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 6133 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, October 26, 2016 The House met at 2 p.m. I met a woman entrepreneur, innovating for the success of her small business, and children striving toward excellence. They are future doctors, lawyers, and tradespeople. I saw it in their eyes; if they get the opportunity, they will succeed. Prayer I speak from experience. Twenty-five years ago, I was a girl child striving for opportunity in a developing country, uniform dusty but Ï (1400) eyes gleaming. [Translation] Today I am even more committed to working with the Minister of The Speaker: It being Wednesday, we will now have the singing International Development and La Francophonie to further the of the national anthem led by the hon. member for Hochelaga. partnership between Canada, Kenya, and other African nations. As a [Members sang the national anthem] donor country, Africa is and should remain a priority for us. *** Ï (1405) STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS BARRIE [Translation] Mr. John Brassard (Barrie—Innisfil, CPC): Mr. Speaker, the TAX HAVENS Canadian Federation of Independent Business recently named Barrie the third most progressive city, out of 122 in the country, for Mr. Gabriel Ste-Marie (Joliette, BQ): Mr. Speaker, today is a entrepreneurial start-ups in 2016. historic day. For the first time, we, the people's representatives, will vote either for or against tax havens. -

La Série Télévisée Little Mosque on the Prairie De Zarqa Nawaz Et Le Discours De L’Authenticité Musulmane Franz Volker Greifenhagen

Document generated on 09/27/2021 7:49 a.m. Théologiques La série télévisée Little Mosque on the Prairie de Zarqa Nawaz et le discours de l’authenticité musulmane Franz Volker Greifenhagen Le dialogue islamo-chrétien Article abstract Volume 19, Number 2, 2011 Muslims, challenged to construct a viable religious identity in a North American context where they are not only a minority, and often members of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1024732ar immigrant communities, but also suffer from prevalent negative stereotypes in DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1024732ar dominant political and media portrayals, often make use of discourses of Muslim authenticity. These discourses frequently invoke a distinction between See table of contents cultural traditions, interpreted as contextual and limited, and “true Islam”, seen as universal and everlasting. Against the backdrop of these discourses, this article analyzes the television comedy series, Little Mosque on the Prairie, created by Zarqa Nawaz. Rather than rejecting cultural expressions of Islam, Publisher(s) Nawaz’s work suggests that an authentic Muslim identity at home in North Faculté de théologie et de sciences des religions, Université de Montréal America is itself a cultural construct, this despite both Muslim and non-Muslim counter-discourses that portray Muslim identity as incommensurate with western cultural contexts. ISSN 1188-7109 (print) 1492-1413 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Greifenhagen, F. V. (2011). La série télévisée Little Mosque on the Prairie de Zarqa Nawaz et le discours de l’authenticité musulmane. Théologiques, 19(2), 151–172. https://doi.org/10.7202/1024732ar Tous droits réservés © Théologiques, 2014 This document is protected by copyright law. -

I Am VOWR": Living Radio in Newfoundland Judith Klassen

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 07:24 Newfoundland Studies "I Am VOWR": Living Radio in Newfoundland Judith Klassen Volume 22, numéro 1, spring 2007 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds22_1art09 Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 0823-1737 (imprimé) 1715-1430 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klassen, J. (2007). "I Am VOWR":: Living Radio in Newfoundland. Newfoundland Studies, 22(1), 205–226. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2007 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ “I Am VOWR”: Living Radio in Newfoundland1 JUDITH KLASSEN In a small Newfoundland outport, a little girl in pigtails goes to Sunday School, by ra- dio. A fishing boat, rocking off the Gaspe coast, picks up schooner reports and news of Newfoundland sent by a radio announcer in a church basement in St. John’s. And, sit- ting in a wheel chair in the Capital City, an invalid has a warm little glow of pride be- cause her small contribution has helped finance a service unique in Newfoundland and one that has gone a long way toward cutting down the lonelines [sic] of the outport Newfoundlander — Wesley United Church’s unique station VOWR. -

Basic TV Channels: St. John's, NL

Basic TV Channels: St. John’s, NL ABC Boston (WCVB) Homes Plus AMI-audio ICI Radio-Canada Télé (MON) Radio Services: AMI-télé ICI RDI 96.9 JACK FM Vancouver AMItv NBC Boston (WBTS) CBAF FM St. John's APTN Newfoundland Legislature CBC Radio One St. John's Aquarium Channel NFL Network CBN FM St. John's Broadcast News NTV St. John`s CHMR FM St. John's CBC Calgary OLN CHOZ FM St. John's CBC News Network/AMI-audio (SAP) OMNI.1 CKIX FM St. John's CBC St. John's OMNI.2 CKSJ FM St. John's CBC Toronto OWN KISS 92.5 Toronto CBC Vancouver PBS Detroit (WTVS) THE FAN 590 Toronto CBC Winnipeg Rogers On Demand VOAR AM St. John's CBS Boston (WBZ) Rogers TV (St. John's) VOCM AM St. John's CHCH Sportsnet East* VOCM-FM St. John's City Calgary Sportsnet ONE* VOWR AM St. John's City Montreal Sportsnet Ontario* City Toronto Sportsnet Pacific* City Vancouver Sportsnet West* CMT Canada Sportsnews CPAC English (& CPAC French SAP) Sunset Channel CPAC French (& CPAC English SAP) The Weather Network CTV Atlantic Halifax Treehouse CTV Calgary TSC CTV News Channel TSN 1* CTV Toronto TSN 3* CTV Two Atlantic TSN 4* CTV Two Toronto TSN 5* CTV Vancouver TV Listings CTV Winnipeg TV5 Daystar Television Network Canada TVA Montreal Fireplace Channel Unis TV FOX Buffalo (WUTV) VICELAND GameTV VisionTV Global BC W Network (East) Global Calgary YES TV Global Maritimes Your World This Week Global Toronto YTV (East) Gusto * Sportsnet and TSN are not included in the TV packages for commercial establishments that have a public viewing area and a liquor license (such as bars and restaurants). -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM