SELECTED LETTERS of WILLIAM MAKEPEACE THACKERAY Also by Edgar E Harden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omar Khayyam

ABU OL-FATH EBN-EBRAHIM ’OMAR OL-KHAYYÁMI OF NISHAPUR 1048 CE May 15, Monday: Traditional date of birth of the Persian mathematician, astronomer, and poet Omar Khayyam يمغياث الدين ابو الفتح عمر بن ابراه Ghiyath al-Din Abu’l-Fath Omar ibn Ibrahim Al-Nisaburi Khayyámi) in Nishapur, the provincial capital of Khurasan in northeastern Iran, a town at an altitude of ,(خيام نيشابوري 3,920 feet. There appears to be no evidence whatever that he was born on this traditional date. It is, presumably, a pious fabrication committed by someone sometime. We think actually he was born in about 1038 to 1048, most likely 1044 — but hey, what does it matter? “Khayyam” means the tent-maker, and although generally he is considered as a Persian, it has also been suggested that he could have belonged to a tribe of Arab origin that settled in Persia. Little is known about his early life except that he was educated at Nishapur and lived there and at Samarqand for most of his life. He was a contemporary of Nidham al-Mulk Tusi. He would be the 1st to be able to solve some cubic equations, to wit, equations of degree three with the unknown raised to the third power and eventually would be recognized as the only person we know of, who was recognizably both a poet and a mathematician. Although patronage opportunities would be available to him, and although he would visit the great centers of learning in Samarqand, Bukhara, Balkh, and Isphahan in order to study and to interact with other scholars, he preferred a calm life devoted to inquiry and did not avail himself of the shah’s court. -

The Letters of Edward Fitzgerald, Volume 1 1830-1850 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LETTERS OF EDWARD FITZGERALD, VOLUME 1 1830-1850 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward FitzGerald | 9780691616162 | | | | | The Letters of Edward Fitzgerald, Volume 1 1830-1850 1st edition PDF Book First Edition Thus. I suppose you never will come back to stay long in England again: I have given you up to a warmer latitude. Shining, shining! How glad I shall be if you can assure me that it is. Since these volumes were completed a large number of letters, addressed by FitzGerald to his life-long friend Mrs. But then I have only read it once; and I think that one is naturally impatient of all matter that does not absolutely touch Cowper: I mean, at the first reading; when one wants to know all about him. I have read nothing else. Garrett, Gilbert James, and others. But it is pleasant to retire to the Tale of a Tub, Tristram Shandy, and Horace Walpole, after being tossed on his canvas waves. God send that p. And yet all this gives a sense of stolen enjoyment to them. You here may judge, by the very nature of things, that I lose no time in answering it. My Titian is a great hit: if not by him, it is as near him as ever was painted. I should travel like you if I had the eyes to see that you have: but, as Goethe says, the eye can but see what it brings with it the power of seeing. Handel, I can never sing it like that. Theodore Hack — Boulge Hall , Woodbridge. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

Salman-Absal-Jami-En.Pdf

Hu 121 SALÁMÁN & ABSÁL AN ALLEGORY TRANSLATED FROM THE PERSIAN OF JÁMI BY EDWARD FITZGERALD LONDON ALEXANDER MORING LTD. THE DE LA MORE PRESS 298 REGENT STREET W MDCCCCIV [1904] This is a translation of an allegorical Sufi poem by the Persian Sufi poet Jami. Nur ad-Din Abd ar-Rahman Jami, (b. 1441 d. 1492), lived in what is today Afghanistan and Uzebekistan. The translator, Edward Fitzgerald, is best known for his translation of the Rubayyat of Omar Khayyam. This book has not been reprinted since it was published in the early 20th century, although the poem has been reprinted in conjunction with other Fitzgerald works. Scanned, proofed and formatted at sacred-texts.com by John Bruno Hare, September 2008. This text is in the public domain in the US because it was published prior to 1923. MY DEAR COWELL, Two years ago, when we began (I for the first time) to read this Poem together, I wanted you to translate it, as something that should interest a few who are worth interesting. You, however, did not see the way clear then, and had Aristotle pulling you by one Shoulder and Prakrit Vararuchi by the other, so as indeed to have hindered you up to this time completing a Version of Hafiz’ best Odes which you had then happily begun. So, continuing to like old Jámi more and more, I must try my hand upon him; and here is my reduced Version of a small Original. What Scholarship it has is yours, my Master in Persian and so much beside; who are no further answerable for all than by well liking and wishing publisht what you may scarce have Leisure to find due fault with. -

[Note: This Is a Pre-Copyedited, Author-Produced PDF of an Article

[Note: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article published as “FitzGerald and the Rubáiyát, In and Out of Time,” Victorian Poetry 46 (2008), 1- 14.] FitzGerald and the Rubáiyát, In and Out of Time Erik Gray This issue of Victorian Poetry commemorates a double anniversary: March 31, 2009, marks both the bicentennial of the birth of Edward FitzGerald and the sesquicentennial of his Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, which was published (give or take a few days) on the poet’s fiftieth birthday.i It is quite fitting that we should celebrate this occasion and at the same time quite ironic. FitzGerald’s poem, after all, seeks to do away with commemoration, and even with time itself: it enjoins the reader to think only of today, abjuring all consideration of past and future. FitzGerald himself moreover, who never liked birthdays in any case, certainly did not celebrate this one. His dearest friend, William Kenworthy Browne, to whom FitzGerald had been passionately attached ever since their first meeting twenty-seven years earlier, had died only the day before.ii Browne was still a young man – he had been only sixteen when he met FitzGerald – and his death was the result of an accident. As FitzGerald described it in a letter to Tennyson, while Browne was “Coming home from hunting the end of January, his Horse was kicked by another: reared, and her hind Legs slipping under her, she fell over and on him, crushing all the middle of his Body. He lived two months with a Patience and Vitality that would have left most Men to die in a Week … and then gave up his Ghost” (Letters 2:333). -

The Second Edition of Edward Fitzgerald's Rubá'iyyát of 'Umar

llttidUi THE SECOND EDITION OF EDWARD FITZGERALD'S RUBA'IYYAT OF 'UMAR KHAYYAM THE SECOND EDITION OF EDWARD FITZGERALD'S rubA'iyyat of 'umar khayyam (LONDON : 1868 : B. QUARITCH) EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES, BY EDWARD HERON-ALLEN LONDON DUCKWORTH AND CO. 1908 A II rights reserved BetJtcation iL/o " ji^ Jl^ ^:S ^ iuU> ^5 j*l-3 ij :Nrour-i-iitaij O Name of Thine, the best heading of a commencement, Without Thy Name how shall I begin my book ? Nizam'i—Leila and Majnun Ion 536^7 Kal 6 fiev rau noLrirav e^ ciWris Movarjs, 6 8e i^ nWrjs e^TjpTrjrai— ovofid^ofiev 8e dvro KarexfraL, to 8i fan rrapaTrXrjcriov e'jj^erai yap— fK 8e TovTuiv Twv TTpoiTOiv daKTvXiwv, T(bv TTOtJ/raJj', aXXoi e^ oXXou ail r]pTr]p.ivoi (ia\ Koi ivdovcria^ovai, ol fi€i> e^ Op(f}ia)s, ol de (k Movddiov 61 di TToXXtii e^ 'Op,r]pov Karexovrdi re koi e'xovrai. Ion 536 * 4-536 «^ 3: 2)1/ av, ft) "lo)v, eis ei Kal KarixTH ^$ 'Ofirjpov, koI eneiSav p-iv ris aXKov Tov TTOirjTov aBr), Kadivdeis re kcL aTTopfls brt, X4yi]s, eireidav Se TovTov TOV TTOirjTov (pdey^yjTaL tis p,f\os, evdvs eypijyopas koX opxeiTai fj '^"' f^'^opels ort Xtyrjs' ov ovS' eiri(rTrjp,T} crov V^'^'X') yap Tixyu TrepX 'Op,fjpov Xeytis a Xiyeis, dXXa diia p.6ipa koi KaTOKaxf], Stfrtrep ol KopvjBavTiS)VTes fKcivov p^ovov alaOdvovTai. tov p,iXovs o^ecos o &i> rj TOV deov i^OTOv tiv KaT€X(>>vTai, Kal els eicetvo to p^eXos Kal crx^paTuiv Kal pt]p,dT(ov eviropovaif tu)v fie hXXwi' ov (j)povTi^ov(riv ovtco Kal(rv, 0) "lav, Trepl pev 'Oprjpov oTav tis p,vrja6fj, (VTropeis, vrepi de tS)v (iXXoJV aTTopeis' tovtov S' e'crrt to uitiou, 6 p epcuTas, 81 on cri) nepl pev 'Op,7]pov eviroptis, wepl 8e tcov (iXX<ov ov, on ov Texv;/ dXXd Oiia pLOipa 'Opijpov 8eiv6s et enaipeTtjs. -

Kaiser-MA-1942.Pdf

A LITERARY COMPARISON BETWEEN WILLIAM HAZLITT'S THE SPIRIT OF THE AGE AND RICHARD HORNE'S A NEW SPIRIT OF THE AGE. BY SISTER MARY LEONARD KAISER, 0. S. E. A THESIS Submitted to the faculty of the Creighton University in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English OMAHA, 1942 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to acknowledge her gratitude to Reverend Mother Lucy Dooley, O.S.B, and to the Sisters of Mount St. Scholastics for the opportunity of pursuing this study. She also wishes to express her sincere appreciation for the valuable assistance so graciously extended by Reverend Paul Smith, S.J. TABLE OP CONTENTS CHAPTERS INTRODUCTION I I THE SPIRIT OF THE AGE 1 II A NEW SPIRIT OP THE AGE 16 III THE TREATMENT OF THE POETS IN HAZLITT AND HORNE 29 IV THE TREATMENT OP THE PROSE WRITERS IN HAZLITT AND HORNE 43 V SAME AUTHORS IN BOTH BOOKS 54 VI CONCLUSION 62 BIBLIOGRAPHY 70 INTRODUCTIOK The old order changeth, yielding place to new Tennyson, Morte D fArthur Change is a universal thing* It is the rise and fall of the tide of existence* It is a natural thing and proof of the rhythm in nature* This element of un rest and continual search for causes in the minds of man is manifested in the words they write, for words are the symbols of thought* These thoughts, translated into the prevailing literature, are the reflection of the change in the universe* In this study of two books, embodying the spirits of two separate ages, we shall see these truths exempli fied* In Maslitt's, The spirit of the -

Chronological Biography of John Forster, 1812-1876

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1927 Chronological biography of John Forster, 1812-1876 Catherine Ritchey The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ritchey, Catherine, "Chronological biography of John Forster, 1812-1876" (1927). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1800. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1800 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'CHROITOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY OP JOHH P0RST5H 1812-1876 ty Catherine Ritchey Presented in partial fulfillment of the req^uirement for the degree of Master of Arts. State University of Montana 19E7 {Signed) Oliairman ^2xam. Oom UMI Number EP35865 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT yaMfiiBOfi riiDRwvng UMI EP35865 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest ProQuest LLC. -

Title 'So You Knew Fitzgerald'-Oscar Wilde and the Rub?Iy?T of Omar

‘So You Knew FitzGerald’-Oscar Wilde and The Title Rub?iy?t of Omar Khayy?m- Author(s) 小宮,彩加 THE JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES MEIJI UNIVERSITY, 21: Citation 1-10 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10291/17922 Rights Issue Date 2015-03-31 Text version publisher Type Departmental Bulletin Paper DOI https://m-repo.lib.meiji.ac.jp/ Meiji University The Journal 01 Humanities ,A 例 iUniv. , Vo l. 21 (地 rch 31 ,2015) ,1- ]0 '80 '80 You Knew FitzGerald': Oscar Wilde and The Rubaiyat o/Omar Khayyam KOMIYA Ay aka 3 'So 'So You Kn ew FitzGerald': Oscar Wilde and The Rubaiyat o/Omar Khayyam KOMIYAAyaka The Picture of Dorian Gray is Oscar Wilde's best 司 known work ,which is often identified withfin-de-siecle , decadent literature. There are actually two versions of The Picture of Dorian Gray: Gray: the original novella forrn version published in Lippincott きMagazine in June 1890 , and the revised revised longer version which appeared in book form in 189 1. L ψ'P incott 主version ,which comprised comprised 13 chapters ,received a storrn of protest from reviewers. It was deemed so immoral that that the July issues of L 伊'P incott sMagazine were withdrawn 仕om bookstalls at railway stations. Although Although Wilde was undefeated by the harsh criticisms , he took some advice seriously. During his his trial , in 1895 ,when Wilde was being tried for ‘gross indecency ,' he admitted that he made some alterations to the original version of The Picture of Dorian Gray because ‘it had been pointed pointed out .. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2015 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

The Impact of Power and Ideology on Edward Fitzgerald's Translation Of

TranscUlturAl, vol. 11.1 (2019), 35-48 https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/tc/index.php/tc The Impact of Power and Ideology on Edward FitzGerald’s Translation of the Rubáiyát: A Postcolonial Approach Bentolhoda Nakhaei University of Lorraine Introduction The Rubáiyát1 refers to a collection of quatrains composed by the Persian poet, Omar Ibn Ibrāhīm-I Nayshāpūrī (1048-1131), known simply as Omar Khayyám in the West. The quatrains of Omar Khayyám were first introduced to the West through the translation of an English writer named Edward FitzGerald (1859). FitzGerald translated Khayyám’s quatrains in the form of five versions of translation: 1859, 1868, 1872, 1879, 1889. However, his translation is a free adaptation and a selection of the Persian poet’s quatrains which is regarded today as a brilliant instance of 19th-century English Literature on its own merit. According to André Lefevere, the act of translation can be regarded as the “rewriting of an original text” (Lefevere xi). In fact, the process of rewriting reflects the ideology of the translator who manipulates the original text so that it will “function in a given society in a given way” (xi). In other terms, for Lefevere, “rewriting is manipulation, undertaken in the service of power […]” (xi). The word power in this context refers to either the power of the writer or the power of the editor. However, since the editorial power on FitzGerald’s translations did not have much effect, this paper will focus on the recognition of the extent of manipulative power of the translator. In other terms, it is aimed to investigate whether FitzGerald has attempted to abuse his colonial power as a British writer while rendering the Persian quatrains. -

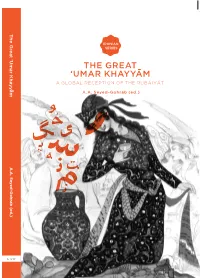

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent.