Jb SDI 2016 477 Kuzn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter 2021 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

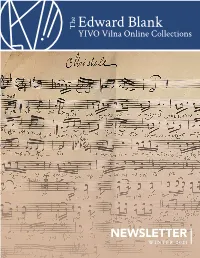

NEWSLETTER winter 2021 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, The Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections team has continued its exceptional work unabated throughout the past nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic under the superb leadership of Stefanie Halpern, Director of the YIVO Archives. The complex work of processing, conservation, and digitization has gone forward uninterrupted and with the enthusiasm and energy that bespeaks the tireless commitment of our YIVO staff. Their dedication is the mark of a vibrant institution, one of which I and the YIVO board are justly proud, as are many others in the global YIVO community. Our team’s collective efforts continually affirm the vitality of YIVO’s mission—preserving and disseminating the heritage of East European Jewish life. We honor their intensive work on the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project much as we honor the sacrifices and dedication of those who came before us and who risked their lives to enable our access to these essential documents and artifacts. I hope you will join me in expressing your appreciation, including by making a gift in support of the Project. We welcome your participation and partnership in our restoration efforts. I also hope that you will explore our Archives and Library, our public and educational programs, our exhibitions, and social media offerings. In these and so many ways, you can help us to ensure that the spirit of YIVO remains a living reality for generations to come. Jonathan Brent Executive Director & CEO CONTACT For more information, please contact the YIVO Development Department: 212.294.6156 [email protected] DONATE ONLINE vilnacollections.yivo.org/Donate COVER: Handwritten music manuscript from a Yiddish operetta, ca. -

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

Zalman Wendroff: the Forverts Man in Moscow

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

The Semitic Component in Yiddish and Its Ideological Role in Yiddish Philology

philological encounters � (�0�7) 368-387 brill.com/phen The Semitic Component in Yiddish and its Ideological Role in Yiddish Philology Tal Hever-Chybowski Paris Yiddish Center—Medem Library [email protected] Abstract The article discusses the ideological role played by the Semitic component in Yiddish in four major texts of Yiddish philology from the first half of the 20th century: Ysroel Haim Taviov’s “The Hebrew Elements of the Jargon” (1904); Ber Borochov’s “The Tasks of Yiddish Philology” (1913); Nokhem Shtif’s “The Social Differentiation of Yiddish: Hebrew Elements in the Language” (1929); and Max Weinreich’s “What Would Yiddish Have Been without Hebrew?” (1931). The article explores the ways in which these texts attribute various religious, national, psychological and class values to the Semitic com- ponent in Yiddish, while debating its ontological status and making prescriptive sug- gestions regarding its future. It argues that all four philologists set the Semitic component of Yiddish in service of their own ideological visions of Jewish linguistic, national and ethnic identity (Yiddishism, Hebraism, Soviet Socialism, etc.), thus blur- ring the boundaries between descriptive linguistics and ideologically engaged philology. Keywords Yiddish – loshn-koydesh – semitic philology – Hebraism – Yiddishism – dehebraization Yiddish, although written in the Hebrew alphabet, is predominantly Germanic in its linguistic structure and vocabulary.* It also possesses substantial Slavic * The comments of Yitskhok Niborski, Natalia Krynicka and of the anonymous reviewer have greatly improved this article, and I am deeply indebted to them for their help. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/�45�9�97-��Downloaded34003� from Brill.com09/23/2021 11:50:14AM via free access The Semitic Component In Yiddish 369 and Semitic elements, and shows some traces of the Romance languages. -

Bridging the “Great and Tragic Mekhitse”: Pre-War European

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

Th Trsformtion of Contmpora Orthodoxy

lïayr. Soloveitchik Haym Soloveitchik teaches Jewish history and thought in the Bernard Revel Graduate School and Stern College for Woman at Yeshiva University. RUP AN RECONSTRUCTION: TH TRSFORMTION OF CONTMPORA ORTHODOXY have occurred within my lifetime in the comniunity in which This essayI live. is The an orthodoxyattempt to in understand which I, and the other developments people my age,that were raised scarcely exists anymore. This change is often described as "the swing to the Right." In one sense, this is an accurate descrip- tion. Many practices, especially the new rigor in religious observance now current among the younger modern orthodox community, did indeed originate in what is called "the Right." Yet, in another sense, the description seems a misnomer. A generation ago, two things pri- marily separated modern Orthodoxy from, what was then called, "ultra-Orthodoxy" or "the Right." First, the attitude to Western culture, that is, secular education; second, the relation to political nationalism, i.e Zionism and the state of IsraeL. Little, however, has changed in these areas. Modern Orthodoxy stil attends college, albeit with somewhat less enthusiasm than before, and is more strongly Zionist than ever. The "ultra-orthodox," or what is now called the "haredi,"l camp is stil opposed to higher secular educa- tion, though the form that the opposition now takes has local nuance. In Israel, the opposition remains total; in America, the utili- ty, even the necessity of a college degree is conceded by most, and various arrangements are made to enable many haredi youths to obtain it. However, the value of a secular education, of Western cul- ture generally, is still denigrated. -

By Gennady Estraikh in August 1935, a Group of Intellectuals Who

QUEST N. 17 – FOCUS A Quest for Yiddishland: The 1937 World Yiddish Cultural Congress by Gennady Estraikh Abstract In August 1935, a group of intellectuals who gathered in Vilna at a jubilee conference of the Jewish Scientific Institute, YIVO, announced the founding of a movement called the Yiddish Culture Front (YCF), whose aim would be to ensure the preservation of Yiddish culture. The article focuses on the congress convened by the YCF in Paris. The congress, a landmark in the history of Yiddishism, opened on September 17, 1937, before a crowd of some 4,000 attendees. 104 delegates represented organizations and institutions from 23 countries. Radically anti-Soviet groups boycotted the convention, considering it a communist ploy. Ironically, the Kremlin cancelled the participation of a Soviet delegation at the last moment. From the vantage point of the delegates, Paris was the only logical center for its World Yiddish Cultural Association (IKUF or YIKUF) created after the congress. However, the French capital was not destined to become the world capital of Yiddish intellectual life. Influential circles of Yiddish literati, still torn by ideological strife rather than united in any common cultural “Yiddishland,” remained concentrated in America, Poland, and the Soviet Union. From Berlin to Paris Preludes to the Congress The Boycott A Phantasm of Yiddishland ___________________ 96 Gennady Estraikh “Where are you coming from?” “From Yiddishland.” “Where are you headed?” “To Yiddishland.” “What kind of journey is this?” “A journey like any other journey.”1 From Berlin to Paris In the years following World War I and the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, Berlin emerged as the European capital of Eastern European Jewish, including Yiddish- speaking and -writing, intellectual émigré life. -

119 Kuznitz, Cecile Esther Readers of This Journal Are Undoubtedly Familiar

Book Reviews 119 Kuznitz, Cecile Esther YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture. Scholarship for the Yiddish Nation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. 307 pp. ISBN 978-1-107-01420-6 Readers of this journal are undoubtedly familiar with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, widely recognized today as the scholarly authority for the standardization of the Yiddish language. During its first, “European period” between the two world wars, YIVO was a global organization with headquar- ters in Vilna, Poland and branches elsewhere in “Yiddishland.” As war engulfed and ultimately consumed the eastern European heartland of Yiddish-speaking Jewry, its American division in New York City was transformed into its world center under the leadership of its guiding spirit Max Weinreich. Given the decisive role played by Weinreich, a path-breaking scholar of the Yiddish language and its cultural history, in shaping both the field of Yiddish Studies and YIVO, it is no surprise that the institute remains closely associated in the contemporary mind with his name and legacy. But YIVO (an acronym for Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut or Yiddish Scientific Institute, the name by which it was known in English into the 1950s as a statement of its commitment to Yiddish) was never the accomplishment of an individual or the expression of a single voice. Nor was academics in its most narrow sense nor the research and cultivation of the Yiddish language ever its exclusive focus. Rather, YIVO, as historian Cecile Kuznitz explains, was the creation of a cohort of scholars and cultural activists animated by a populist mission, many of whom knew each other since their days as politically engaged students at the University of St. -

Simon Goldberg

Simon Goldberg B.A., Yeshiva University, 2012 M.A., Haifa University, 2015 Shirley and Ralph Rose Fellow Simon Goldberg, recipient of the Hilda and Al Kirsch research award, examines documents fashioned in the Kovno (Kaunas) ghetto in Lithuania to explore the broader question of how wartime Jewish elites portrayed life in the ghetto. The texts that survived the war years in Kovno offer rich insights into ghetto life: they include an anonymous history written by Jewish policemen; a report written by members of the ghetto khevre kedishe (burial society); and a protocol book detailing the Ältestenrat’s wartime deliberations. Yet these documents primarily reflect the perspectives of a select few. Indeed, for decades, scholarship on the Holocaust in Kovno has been dominated by the writings of ghetto elites, relegating the testimonies of Jews who did not occupy positions of authority during the war to the margins. Goldberg’s dissertation explores how little-known accounts of the Kovno ghetto both challenge and broaden our understanding of wartime Jewish experience. At the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Goldberg examined records from the Central States Archives of Lithuania (LCVA). LCVA’s vast repository includes protocols, daily reports, arrest records, and meeting minutes that shed light on the institution of the Jewish police in the Kovno ghetto and the chronicle its members wrote in 1942 and 1943. The LCVA materials also include songs and poems that highlight social and cultural aspects of Jewish life across ghetto society. As the 2018-2019 Fellow in Baltic Jewish History at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, Goldberg studied the early historiography of the Kovno ghetto as reflected in the various newspapers and periodicals published in DP camps in Germany and Italy, including Unzer Weg and Ba’Derech. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture Cecile Esther Kuznitz Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01420-6 — YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture Cecile Esther Kuznitz Frontmatter More Information YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture This book is the i rst history of YIVO, the original center for Yiddish scholarship. Founded by a group of Eastern European intellectuals after World War I, YIVO became both the apex of secular Yiddish culture and the premier institution of Diaspora Nationalism, which fought for Jewish rights throughout the world. From its headquarters in Vilna (then Poland and now Lithuania), YIVO tried to balance schol- arly objectivity with its commitment to the Jewish masses. Using newly recovered documents that were believed destroyed by Hitler and Stalin, Cecile Esther Kuznitz tells for the i rst time the compelling story of how these scholars built a world-renowned institution despite dire pov- erty and antisemitism. She raises new questions about the relationship between Jewish cultural and political work and analyzes how national- ism arises outside of state power. Cecile Esther Kuznitz is an associate professor of history and the direc- tor of Jewish Studies at Bard College. A magna cum laude graduate of Harvard University, she received her Ph.D. from Stanford University. Her articles have been published in The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2008), The Encyclopaedia Judaica (2007), The Worlds of S. An-sky (2006), The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies (2002), and Yiddish Language and Culture: Then and Now (1998). She previously taught at Georgetown University and has held fellowships at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.