US-Southeast Asia Relations: After Bali, Before Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia Beyond Reformasi: Necessity and the “De-Centering” of Democracy

INDONESIA BEYOND REFORMASI: NECESSITY AND THE “DE-CENTERING” OF DEMOCRACY Leonard C. Sebastian, Jonathan Chen and Adhi Priamarizki* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: TRANSITIONAL POLITICS IN INDONESIA ......................................... 2 R II. NECESSITY MAKES STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: THE GLOBAL AND DOMESTIC CONTEXT FOR DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA .................... 7 R III. NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ................... 12 R A. What Necessity Inevitably Entailed: Changes to Defining Features of the New Order ............. 12 R 1. Military Reform: From Dual Function (Dwifungsi) to NKRI ......................... 13 R 2. Taming Golkar: From Hegemony to Political Party .......................................... 21 R 3. Decentralizing the Executive and Devolution to the Regions................................. 26 R 4. Necessary Changes and Beyond: A Reflection .31 R IV. NON NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ............. 32 R A. After Necessity: A Political Tug of War........... 32 R 1. The Evolution of Legislative Elections ........ 33 R 2. The Introduction of Direct Presidential Elections ...................................... 44 R a. The 2004 Direct Presidential Elections . 47 R b. The 2009 Direct Presidential Elections . 48 R 3. The Emergence of Direct Local Elections ..... 50 R V. 2014: A WATERSHED ............................... 55 R * Leonard C. Sebastian is Associate Professor and Coordinator, Indonesia Pro- gramme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of In- ternational Studies, Nanyang Technological University, -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Redalyc.Democratization and TNI Reform

UNISCI Discussion Papers ISSN: 1696-2206 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Marbun, Rico Democratization and TNI reform UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 15, octubre, 2007, pp. 37-61 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76701504 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 15 (Octubre / October 2007) ISSN 1696-2206 DEMOCRATIZATIO A D T I REFORM Rico Marbun 1 Centre for Policy and Strategic Studies (CPSS), Indonesia Abstract: This article is written to answer four questions: what kind of civil-military relations is needed for democratization; how does military reform in Indonesia affect civil-military relations; does it have a positive impact toward democratization; and finally is the democratization process in Indonesia on the right track. Keywords: Civil-military relations; Indonesia. Resumen: Este artículo pretende responder a cuatro preguntas: qué tipo de relaciones cívico-militares son necesarias para la democratización; cómo afecta la reforma militar en Indonesia a las relaciones cívico-militares; si tiene un impacto positivo en la democratización; y finalmente, si el proceso de democratización en Indonesia va por buen camino. Palabras clave: relaciones cívico-militares; Indonesia. Copyright © UNISCI, 2007. The views expressed in these articles are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNISCI. Las opiniones expresadas en estos artículos son propias de sus autores, y no reflejan necesariamente la opinión de U*ISCI. -

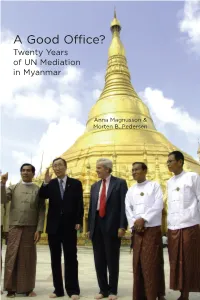

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance

Policy Studies 23 The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Marcus Mietzner East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the theme of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American understanding of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Policy Studies 23 ___________ The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance _____________________ Marcus Mietzner Copyright © 2006 by the East-West Center Washington The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance by Marcus Mietzner ISBN 978-1-932728-45-3 (online version) ISSN 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

Peace Without Justice? the Helsinki Peace Process in Aceh Edward Aspinall

Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue rAprile 2008port Peace without justice? The Helsinki peace process in Aceh Edward Aspinall Report The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue is an independent and impartial foundation, based Contents in Geneva, that promotes and facilitates dialogue to resolve Acknowledgement armed conflicts and reduce civilian suffering. Introduction and overview 5 114, rue de lausanne ch-1202 geneva 1. The centrality of human rights and justice issues in Aceh 7 switzerland [email protected] 2. Aceh in its Indonesian setting 9 t: + 41 22 908 11 30 f: +41 22 908 11 40 www.hdcentre.org 3. Limited international involvement 12 © Copyright Henry Dunant Centre for 4. Justice issues in the negotiations 16 Humanitarian Dialogue, 2007 Reproduction of all or part of this 5. Implementation of the amnesty 19 publication may be authorised only with written consent and 6. Compensation without justice 22 acknowledgement of the source. Broad definition and difficulties in delivery 23 Edward Aspinall (edward,aspinall@ Compensation or assistance? 24 anu.edu.au) is a Fellow in the Department of Political and 7. Debates about the missing justice mechanisms 27 Social Change, Research School Human Rights Court 27 of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. He Truth and Reconciliation Commission 29 specialises in Indonesian politics and is the author of Opposing 8. The Aceh Monitoring Mission: could more have 31 Suharto: Compromise, Resistance been done? and Regime Change in Indonesia (Stanford University Press, 2005). His new book on the history Conclusion 36 of the Aceh conflict and peace process, provisionally entitled Islam References 39 and Nation: Separatist Rebellion in Aceh, Indonesia, will also be published by Stanford University Acronyms and abbreviations 43 Press. -

Prologue This Report Is Submitted Pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264)

Prologue This report is submitted pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264). Section 4 of this law provides, in part, that: ―The President shall from time to time as occasion may require, but not less than once each year, make reports to the Congress of the activities of the United Nations and of the participation of the United States therein.‖ In July 2003, the President delegated to the Secretary of State the authority to transmit this report to Congress. The United States Participation in the United Nations report is a survey of the activities of the U.S. Government in the United Nations and its agencies, as well as the activities of the United Nations and those agencies themselves. More specifically, this report seeks to assess UN achievements during 2007, the effectiveness of U.S. participation in the United Nations, and whether U.S. goals were advanced or thwarted. The United States is committed to the founding ideals of the United Nations. Addressing the UN General Assembly in 2007, President Bush said: ―With the commitment and courage of this chamber, we can build a world where people are free to speak, assemble, and worship as they wish; a world where children in every nation grow up healthy, get a decent education, and look to the future with hope; a world where opportunity crosses every border. America will lead toward this vision where all are created equal, and free to pursue their dreams. This is the founding conviction of my country. It is the promise that established this body. -

Indonesia Says Drive Against Separatists Will Not End Soon

July 9, 2003 Indonesia Says Drive Against Separatists Will Not End Soon By JANE PERLEZ JAKARTA, Indonesia, July 8 — The Indonesian military has now declared that its tough offensive against rebels in the northern province of Aceh, originally supposed to last six months, would last much longer, maybe even 10 years. That statement Sunday by Gen. Endriartono Sutarto to Indonesian reporters followed the first public rebuke by Washington for Indonesia's conduct of the war, and a meeting between a senior Bush administration official and President Megawati Sukarnoputri in which she was urged to end the nearly 30-year-long conflict. Washington's public and private diplomacy — including meetings between the president and a National Security Council official, Karen Brooks, and a meeting between Ms. Brooks and General Endriartono — appear to have had little impact on the conduct of the military in Aceh. According to estimates by the Indonesian military, tens of thousands of civilians have been forced from their homes by the army and placed in relocation camps. The number of civilians killed is estimated by the Indonesian police to be about 150. Western officials assert that the civilian death toll is considerably higher. At a time when the power of the Indonesian military is on the rise again, the United States appears to have little influence among the officers whose cooperation it wants for the campaign against terrorism, Indonesian and Western officials said. The Indonesian police have been the most important force in rounding up suspected terrorists. Those officials said the Army chief of staff, Gen. Ryamizard Ryacudu, argued at a recent meeting of his generals that training for Indonesian officers in the United States would be unnecessary, and even counterproductive. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly

Sixty-seventh session of the General Assembly To convene on United Nations 18 September 2012 List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly Session Year Name Country Sixty-seventh 2012 Mr. Vuk Jeremić (President-elect) Serbia Sixty-sixth 2011 Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser Qatar Sixty-fifth 2010 Mr. Joseph Deiss Switzerland Sixty-fourth 2009 Dr. Ali Abdussalam Treki Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2009 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-third 2008 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-second 2007 Dr. Srgjan Kerim The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixty-first 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixtieth 2005 Mr. Jan Eliasson Sweden Twenty-eighth special 2005 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Fifty-ninth 2004 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2004 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia (resumed twice) 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-eighth 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-seventh 2002 Mr. Jan Kavan Czech Republic Twenty-seventh special 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea (resumed) 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Fifty-sixth 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Twenty-sixth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fifth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Fifty-fifth 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fourth special 2000 Mr. Theo-Ben Gurirab Namibia Twenty-third special 2000 Mr. -

The United Nations at 70 Isbn: 978-92-1-101322-1

DOUBLESPECIAL DOUBLESPECIAL asdf The magazine of the United Nations BLE ISSUE UN Chronicle ISSUEIS 7PMVNF-**t/VNCFSTt Rio+20 THE UNITED NATIONS AT 70 ISBN: 978-92-1-101322-1 COVER.indd 2-3 8/19/15 11:07 AM UNDER-SECRETARY-GENERAL FOR COMMUNICATIONS AND PUBLIC INFORMATION Cristina Gallach DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATION Maher Nasser EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Ramu Damodaran EDITOR Federigo Magherini ART AND DESIGN Lavinia Choerab EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Lyubov Ginzburg, Jennifer Payulert, Jason Pierce SOCIAL MEDIA ASSISTANT Maria Laura Placencia The UN Chronicle is published quarterly by the Outreach Division of the United Nations Department of Public Information. Please address all editorial correspondence: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 1 212 963-6333 By fax 1 917 367-6075 By mail UN Chronicle, United Nations, Room S-920 New York, NY 10017, USA Subscriptions: Customer service in the USA: United Nations Publications Turpin Distribution Service PO Box 486 New Milford, CT 06776-0486 USA Email: [email protected] Web: ebiz.turpin-distribution.com Tel +1-860-350-0041 Fax +1-860-350-0039 Customer service in the UK: United Nations Publications Turpin Distribution Service Pegasus Drive, Stratton Business Park Biggleswade SG18 8TQ United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Web: ebiz.turpin-distribution.com Tel +1 44 (0) 1767 604951 Fax +1 44 (0) 1767 601640 Reproduction: Articles contained in this issue may be reproduced for educational purposes in line with fair use. Please send a copy of the reprint to the editorial correspondence address shown above. However, no part may be reproduced for commercial purposes without the expressed written consent of the Secretary, Publications Board, United Nations, Room S-949 New York, NY 10017, USA © 2015 United Nations. -

High-Level Seminar on Peacebuilding, National Reconciliation and Democratization in Asia (Venue: UN University) General Chairman: Mr

High-Level Seminar on Peacebuilding, National Reconciliation and Democratization in Asia (Venue: UN University) General Chairman: Mr. Yasushi Akashi Introductory remarks: Mr. Yasushi Akashi, Representative of the Government of Japan on Peace-Building, Rehabilitation 9:00- Opening and Reconstruction of Sri Lanka Session 9:05- Keynote Speech: H.E. Mr. Fumio Kishida, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Japan H.E. Dr. José Ramos-Horta, Former President , The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (Chair of the High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations) 9:20 - 10:20 Mr. Mangala Samaraweera, Minister of Foreign Affairs , the Government of Sri Lanka Speech session H.E. Al Haj Murad Ebrahim, Chairman of Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Mr. Yohei Sasakawa, Special Envoy of the Government of Japan for National Reconciliation in Myanmar Morning Chair: Dr. David Malone, Rector of the United Nations University Session H.E. Dr. Surin Pitsuwan, Former Secretary-General of ASEAN 10:30 - 12:00 Dr. Akihiko Tanaka, President of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Interactive session Ms. Noeleen Heyzer, Special Advisor of the UN Secretary-General for Timor-Leste Dr. Takashi Shiraishi, President of the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies Prof. Akiko Yamanaka, Special Ambassador for Peacebuilding, Japan Panel Discussion 1 Panel Discussion 2 Panel Discussion 3 Consolidation of Peace and Socio- Harmonization in Diversity and Peacebuilding and Women and Children Economic Development (Politico- Moderation (Socio-Cultural Aspect) Economic Aspect) 【Moderator】 【Moderator】 【Moderator】 Dr. Toshiya Hoshino, Professor, Vice Mr. Sebastian von Einsiedel, Director, Prof. Akiko Yuge, Professor, Hosei President, Osaka University the Centre for Policy Research, United University (Former Director, Bureau of Nations University Management, UNDP) 【Panelists】 【Panelists】 【Panelists】 <Cambodia> <Malaysia> <Philippines> H.E.