Radio's Big Bully

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Broadcast Applications 12/8/2009

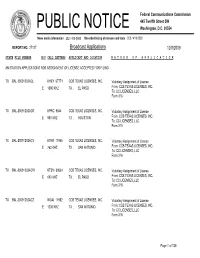

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27127 Broadcast Applications 12/8/2009 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING TX BAL-20091202ACL KHEY 67771 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 1380 KHZ TX , EL PASO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACR KPRC 9644 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 950 KHZ TX , HOUSTON From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACV KTKR 11945 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 760 KHZ TX , SAN ANTONIO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACW KTSM 69561 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 690 KHZ TX , EL PASO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACZ WOAI 11952 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 1200 KHZ TX , SAN ANTONIO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 139 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27127 Broadcast Applications 12/8/2009 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING WA BAL-20091202ADB KHHO 18523 ACKERLEY BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License OPERATIONS, LLC E 850 KHZ From: ACKERLEY BROADCASTING OPERATIONS, LLC WA , TACOMA To: CITICASTERS LICENSES, INC. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-210223-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/23/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000131574 Minor FM KLVJ 51503 Main 102.1 ENCINITAS, CA EDUCATIONAL 02/19/2021 Granted Modification MEDIA FOUNDATION From: To: 0000130766 Assignment LPD K36NB-D 187605 36 INCLINE VILLAGE MIRIAM MEDIA, INC. 02/19/2021 Granted of , NV Authorization From: MIRIAM MEDIA, INC. To: Gray Television Licensee, LLC 0000135321 License To FX K221FI 145577 92.1 MEXIA, TX TEMPLO DE DIOS, 02/19/2021 Granted Cover INC. 1 From: To: 0000130630 Transfer of FM KEHH 52897 Main 92.3 LIVINGSTON, TX Hope Media Group 02/19/2021 Granted Control From: Hope Media Group (Old Board) To: Hope Media Group (New Board) 0000130635 Transfer of FM KXBJ 36507 Main 96.9 EL CAMPO, TX Hope Media Group 02/19/2021 Granted Control From: Hope Media Group (Old Board) To: Hope Media Group (New Board) 0000130640 Transfer of FM KXNG 72685 Main 91.7 HOUSTON, TX Hope Media Group 02/19/2021 Granted Control From: Hope Media Group (Old Board) To: Hope Media Group (New Board) Page 1 of 10 REPORT NO. PN-2-210223-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/23/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Media Studies College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/ms Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kidd, D. (2005). Clear channel and the public airwaves. In E. Cohen (Ed.), News incorporated (pp. 267-285). New York: Prometheus Books. Copyright © 2005 by Elliot D. Cohen. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 13 CLEAR CHANNEL AND THE PUBLIC AIRWAVES DOROTHY KIDD UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO With research assistance from Francisco McGee and Danielle Fairbairn Department of Media Studies, University of San Francisco DOROTHY KIDD, a professor of media studies at the University of San Francisco, has worked extensively in community radio and television. In 2002 Project Censored voted her article "Legal Project to Challenge Media Monopoly " No. 1 on its Top 25 Censored News Stories list. Pub lishing widely in the area of community media, her research has focused on the emerging media democracy movement. INTRODUCTION or a company with close ties to the Bush family, and a Wal-mart-like F approach to culture, Clear Channel Communications has provided a surprising boost to the latest wave of a US media democratization movement. -

Kdge, Kdmx, Kegl, Kfxr, Khks, Kzps Eeo Public File Report I

Page: 1/12 KDGE, KDMX, KEGL, KFXR, KHKS, KZPS EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2018 - March 31, 2019 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Outside Sales Account Executive 1-3, 5, 7-12, 15-22, 24-33, 35-37 36 Outside Sales Account Executive 1-3, 5, 7-12, 15-22, 24-33, 35-37 36 Outside Sales Account Executive 1-3, 5, 7-12, 15-22, 24-33, 35-37 36 Outside Sales Account Executive 1-3, 5, 7-13, 15-28, 30-33, 35-37 36 1-3, 5, 7-13, 15, 17-22, 24-28, 30-33, Outside Sales Account Executive 12 35, 37 1-3, 5, 7-13, 15, 17-22, 24-28, 30-33, Outside Sales Account Executive 10 35, 37 Promotions Coordinator - KHKS and KZPS 1-3, 5-16, 19-22, 24-27, 30-37 14 National Promotions Coordinator 1-22, 24-28, 30-33, 35-37 14 1-11, 14-15, 17, 19-22, 24-28, 30-33, Local Sales Project Coordinator 14 35, 37 Promotions Coordinator - KEGL and KZPS 1-15, 17, 19-22, 24-28, 30-33, 35-37 14 This Report was modified in April 2019 to address reporting issues. Page: 2/12 KDGE, KDMX, KEGL, KFXR, KHKS, KZPS EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2018 - March 31, 2019 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period African American Chamber of Commerce PO Box 5488 Portland, Oregon 97228 1 Phone : 503-244-5794 N 0 Email : [email protected] Roy Jay Amercian Broadcasting School 712 North Watson Road Suite 200 Arlington, Texas 76011 2 Phone : 817-695-2474 N 0 Email : [email protected] Michelle McConnell Career Connection 9800 Preston Rd #232 Dallas, Texas 75230 3 Phone : (214) 739-3924 N 0 Email : [email protected] Lisa Miller Career Resources Center 3001 S. -

MMR 24-7 Song Airplay Detail 5/27/14, 11:45 AM

MMR 24-7 Song Airplay Detail 5/27/14, 11:45 AM 7 Day NICO & VINZ Please set all print margins to 0.50 Song Analysis Am I Wrong Warner Bros. Mediabase - All Stations (U.S.) - by Format LW: May 13 - May 19 TW: May 20 - May 26 Updated: Tue May 27 3:17 AM PST N Sng Rnk Spins Station (Click Graphic for Mkt e @Station Market Format Trade TW lw +/- -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7to Airplay Trends) Rank w (currents) Date KDWB-FM * 1 16 Minneapolis Top 40 Mediabase 114 70 44 19 15 13 16 17 16 18 453 WZEE-FM * 5 99 Madison, WI Top 40 Mediabase 80 36 44 13 9 11 13 10 13 11 264 WXXL-FM * 3 33 Orlando Top 40 Mediabase 78 73 5 12 8 9 12 12 13 12 326 WKCI-FM * 5 121 New Haven, CT Top 40 Mediabase 77 40 37 14 8 8 12 13 15 7 292 WFBC-FM * 8 59 Greenville, SC Top 40 Mediabase 73 69 4 10 10 11 10 11 10 11 367 WNOU-FM * 10 40 Indianapolis Top 40 Mediabase 73 63 10 9 10 9 11 12 10 12 319 WVHT-FM * 9 43 Norfolk Top 40 Mediabase 71 34 37 10 9 9 10 11 11 11 199 WKXJ-FM * 6 107 Chattanooga Top 40 Mediabase 69 40 29 13 6 6 14 12 12 6 210 KMVQ-FM * 6 4 San Francisco Top 40 Mediabase 67 68 -1 10 8 7 11 11 10 10 384 KFRH-FM * 11 32 Las Vegas Top 40 Mediabase 67 65 2 9 8 10 9 10 11 10 420 WXZO-FM * 13 143 Burlington, VT Top 40 Mediabase 66 44 22 11 7 8 10 11 11 8 228 KBFF-FM * 5 23 Portland, OR Top 40 Mediabase 65 72 -7 7 8 7 10 12 10 11 327 KREV-FM 9 4 San Francisco Top 40 Mediabase 65 60 5 9 9 12 9 9 9 8 192 WDJX-FM * 5 54 Louisville Top 40 Mediabase 64 61 3 10 9 10 10 8 9 8 318 WKSC-FM * 10 3 Chicago Top 40 Mediabase 63 38 25 10 7 9 9 10 9 9 200 WJHM-FM * 10 33 Orlando Top -

Industry, ASCAP Agree Him As VP /GM at the San Diego Seattle, St

ISSUE NUMBER 646 THE INDUSTRY'S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER AUGUST 1, 1986 WARSHAW NEW KFSD VP /GM I N S I D E: RADIO BUSINESS Rosenberg Elevated SECTION DEBUTS To Lotus Exec. VP This week R &R expands the Transactions page into a two -page Radio Business section. This week and in coming weeks, you'll read: Features on owners, brokers, dealmakers, and more Analyses on trends in the ever -active station acquisition field Graphs and charts summarizing transaction data Financial data on the top broadcast players And the most complete and timely news available on station transactions. Hal Rosenberg Dick Warshaw Starts this week, Page 8 KFSD/San Diego Sr. VP/GM elevated to Exec. VP for Los Hal Rosenberg has been Angeles-based parent Lotus ARBITRON RATINGS RESULTS COMPROMISE REACHED Communications, which owns The spring Arbitrons for more top 14 other stations in California. markets continue to pour in, including Texas, Arizona, Nevada, Illi- this week figures for Houston, Atlanta, nois, and Maryland. Succeeding Industry, ASCAP Agree him as VP /GM at the San Diego Seattle, St. Louis, Kansas Cincinnati, Classical station is National City, Tampa, Phoenix, Denver, Miami, Sales Manager Dick Warshaw. and more. On 7.5% Rate Hike Rosenberg, who had been at Page 24 stallments, one due by the end After remaining deadlocked KFSD since it was acquired by Increases Vary of this year, and the other. by for several years, ASCAP and Lotus in 1974, assumes his new CD OR NOT CD: By Station next April. The new rates will the All- Industry Radio Music position January 1, 1987. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

102.1 the Edge to Host Fundraiser for Local Ebola Victims Jagger Mornings to Broadcast Live from Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas

102.1 The Edge To Host Fundraiser for Local Ebola Victims Jagger Mornings to Broadcast Live From Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas Dallas/Ft. Worth, TX. – October 23, 2014 – Jagger Mornings, 102.1 The Edge’s Alternative morning show, announced today an on-air fundraiser for local Ebola victims - nurses Nina Pham and Amber Vinson, and the family of Thomas Duncan. The morning show will broadcast live from the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital to enlist community support for the fundraiser on Friday, October 24, from 6 – 10 a.m. On-air personalities from Jagger Mornings, including Chris Jagger, Mondo Mike Vasquez and Jasmine Sadry, will broadcast live alongside special guests Mike Rawlings, Dallas Mayor and Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks. Donations will help support the victims and their families while they rebuild their lives in the wake of the recent Ebola outbreak. “Jagger Mornings is proud to join with listeners and the DFW community to help local Ebola victims get back on their feet,” said Jagger, on-air personality and host of Jagger Mornings on 102.1 The Edge. “Nina Pham and Amber Vinson spend every day of their lives helping people in our own community, including the family of Thomas Duncan. Now, it’s our turn to help.” The on-air fundraiser will broadcast from the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital at 8200 Walnut Hill Lane from 6 – 10 a.m. on Friday, October 24. For more information about the on-air fundraiser and to donate to the victims’ individual funds online, visit www.kdge.com. For up-to-minute information on 102.1 The Edge, log on to www.kdge.com or listen to 102.1 The Edge on-air or online via the station’s website, as well as on iHeartRadio.com and the iHeartRadio mobile app, iHeartMedia’s all-in-one music streaming and digital radio service. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016 Welcome Letter . 1 In Memoriam . 2-3 Carol & Peter Coxhead . 4-5 Competitive Grants . 6-9 Jeanine & Peter Karns . 10-11 Community Foundation Funds . 12-17 Pamela & Scott Gibson . 18-19 Stewardship . 20-21 Old Bill’s Fun Run for Charities . 22-29 Youth Philanthropy . 30-31 Nonprofit Workshops . 32 Board & Staff . 33 Legacy Society . 34 Community Foundation of Teton Valley . 35 Key Financial Indicators . 36-37 COVER PHOTO: ROGER HAYDEN Animal Adoption Center Henry Ford famously said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse .” Visionaries start with the fundamental problem, not with current answers . Twenty years ago, Mr . and Mrs . Old Bill created a new vehicle for fundraising that inspired all of us to enrich the community by investing in local nonprofits . In spite of its name, Old Bill’s Fun Run is full of youthful energy, and its 20th anniversary broke all WELCOME previous records . Combined with matching funds donated by Mr . and Mrs . Old Bill and 62 other Co-Challengers, Old Bill’s 2016 raised over $12 .1 million . Participating nonprofits received matching grants equating to 55% of the first $30,000 they raised themselves . Over the past 20 years, Old Bill's Fun Run has raised more than $133 million because of one couple’s visionary initiative . In 2016, one out of every three households participated in this grassroots fundraiser where the median gift size is $250 . At the Community Foundation, we help donors fulfill their visions by simplifying their giving and providing guidance about critical issues in our community . -

2021 Iheartradio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 iHeartRadio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM hotabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400