Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

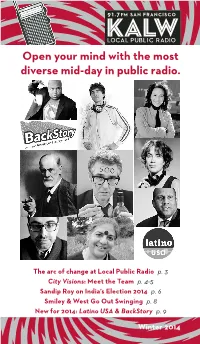

Open Your Mind with the Most Diverse Mid-Day in Public Radio

Open your mind with the most diverse mid-day in public radio. The arc of change at Local Public Radio p. 3 City Visions: Meet the Team p. 4-5 Sandip Roy on India’s Election 2014 p. 6 Smiley & West Go Out Swinging p. 8 New for 2014: Latino USA & BackStory p. 9 Winter 2014 KALW: By and for the community . COMMUNITY BROADCAST PARTNERS AIA, San Francisco • Association for Continuing Education • Berkeley Symphony Orchestra • Burton High School • East Bay Express • Global Exchange • INFORUM at The Commonwealth Club • Jewish Community Center of San Francisco • LitQuake • Mills College • New America Media • Oakland Asian Cultural Center • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UC Berkeley • Other Minds • outLoud Radio Radio Ambulante • San Francisco Arts Commission • San Francisco Conservatory of Music • San Quentin Prison Radio • SF Performances • Stanford Storytelling Project • StoryCorps • Youth Radio KALW VOLUNTEER PRODUCERS Rachel Altman, Wendy Baker, Sarag Bernard, Susie Britton, Sarah Cahill, Tiffany Camhi, Bob Campbell, Lisa Carmack, Lisa Denenmark, Maya de Paula Hanika, Julie Dewitt, Matt Fidler, Chuck Finney, Richard Friedman, Ninna Gaensler-Debs, Mary Goode Willis, Anne Huang, Eric Jansen, Linda Jue, Alyssa Kapnik, Carol Kocivar, Ashleyanne Krigbaum, David Latulippe, Teddy Lederer, JoAnn Mar, Martin MacClain, Daphne Matziaraki, Holly McDede, Lauren Meltzer, Charlie Mintz, Sandy Miranda, Emmanuel Nado, Marty Nemko, Erik Neumann, Edwin Okong’o, Kevin Oliver, David Onek, Joseph Pace, Liz Pfeffer, Marilyn Pittman, Mary Rees, Dana Rodriguez, -

The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 7 Number 2 Article 1 3-1-1987 Radio-Active Fallout and an Uneasy Truce - The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars Jonathan Michael Roldan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan Michael Roldan, Radio-Active Fallout and an Uneasy Truce - The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars, 7 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 217 (1987). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol7/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADIO-ACTIVE FALLOUT AND AN UNEASY TRUCE-THE AFTERMATH OF THE PORN ROCK WARS Jonathan Michael Roldan * "Temperatures rise inside my sugar walls." - Sheena Easton from the song "Sugar Walls."' "Tight action, rear traction so hot you blow me away... I want a piece of your action." - M6tley Criie from the album Shout at the Devil.2 "I'm a fairly with-it person, but this stuff is curling my hair." - Tipper Gore, parent.3 "Fundamentalist frogwash." - Frank Zappa, musician.4 I. OVERTURE TO CONFLICT It began as an innocent listening of Prince's award-winning album, "Purple Rain,"5 and climaxed with heated testimony before the Senate Committee on Commerce in September 1985.6 In the interim the phrase "cleaning up the air" took on new dimensions as one group of parents * B.A., Journalism/Political Science, Cal. -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education

Advance Praise for Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education “The space for dissent and real democratic debate is quickly shrinking both in public life and academic institutions in western democracies. Today, the cries of ‘fake news’ make the loudest (though rarely the best informed) voices the site of authority and truth. This volume helps readers in higher education ask critical and conscious questions about what it means to con- tend for truth. It is an important and significant read for those who want the intellectual space to remain a terrain for thinkers.” —Gloria Ladson-Billings, author of The Dreamkeepers “This deep and layered book maps the path toward a university based on eth- ics and justice rather than corporate needs and military standards. It reaches anyone who wants to understand the social, political, and economic trends that define our times. It is an outstanding contribution to the scholarship on higher education.” —William Ayers, author of Teaching with Conscience in an Imperfect World “Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education is a rich and multi-layered examina- tion of the impact of corporatization on our universities, as well as how they can be reclaimed. Highly recommended.” —James Turk, editor of Academic Freedom in Conflict dissident knowledge in higher education edited with an introduction by marc spooner & James MCNinch © 2018 University of Regina Press “An Interview with Noam Chomsky” © 2016 Noam Chomsky, Marc Spooner, and James McNinch This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. See www.creativecommons.org. The text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given to the original author. -

~~;Lyfc~Mmunications, Inc. F-1ECEIVEO

LAW OFFICES MICHAEL COUZENS 385 EIGHTH STREET - SECOND FL,?OR ,,,' ADDITIONAL TELEPHONE 9J.~3 ~l 2 20 f11 f~t'LiNG ADDRESS: (4151 621-4030 SAN FRANCISCO. CALIFORNIA P,O. BOX NO. 33127 TELEX NO. 9102400363 ,WA~INGTON. DC 20033 .~ {~; ~ TELECOPIER (4151 626-5788 J'-, '.' .. 4 June 1991 ", . ,,\., j ~, ....' 'i "'J ,_.. L J '1'"\ c. \'..J C. \. '"-- Donna R. Searcy, Secretary FCC 1919 M Street, N.W. Room 222 Washington, D.C. 20554 reG MAll BHAI\JCH Re: Dragonfly Communications, Inc. Application for New Broadcast FM Station, Healdsburg, CA (BPH 9l02llMA) Dear Ms. Searcy: Submitted here, on behalf of Dragonfly Communications, Inc., are an original and two copies of an amendment to the application referred to above, "Amendment No.1." The purposes of the amendment are to furnish (1) a new Exhibit No.3, setting forth an integration proposal and (2) a recomputed station coverage, based on a more precise method of computation. The engineering parameters of the proposed facility are unchanged. Any questions with respect to this matter should be directed to the undersigned. Respectfully submitted, / . •I , / I 1..-" I ,I I , ~~:tael Couzens, • ~~;lyfC~mmunications, Inc. f-1ECEIVEO JUN 4 199/ ,~CC MAIL BRANCH Dragonfly Communcations, Inc. BPH 910211MA June 3, 1991 Amendment No.1 CERTIFICATION On behalf of Dragonly Communications, Inc., I certify that the content of the foregoing Amendment No.1 is true, under the penalties for perjury provided in the laws of the United states. Dated: By: r4~ Philip A. Tymon, Secretary/Treasurer Dragonfly Communications, Inc. Healdsburg, CA' BPH 910211MA RECEIVED Exhibit No.3 ..4 1991 March 30, 1991 (Question IV-B, PFcY~ MAIL BRANCH 1. -

Barbara Cochran

Cochran Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive More Inclusive, Local, More More Rethinking Media: Public Rethinking PUBLIC MEDIA More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive A WHITE PAPER BY BARBARA COCHRAN Communications and Society Program 10-021 Communications and Society Program A project of the Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program A project of the Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive A White Paper on the Public Media Recommendations of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy written by Barbara Cochran Communications and Society Program December 2010 The Aspen Institute and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation invite you to join the public dialogue around the Knight Commission’s recommendations at www.knightcomm.org or by using Twitter hashtag #knightcomm. Copyright 2010 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute One Dupont Circle, NW Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20036 Published in the United States of America in 2010 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-536-6 10/021 Individuals are encouraged to cite this paper and its contents. In doing so, please include the following attribution: The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program,Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive, Washington, D.C.: The Aspen Institute, December 2010. For more information, contact: The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program One Dupont Circle, NW Suite 700 Washington, D.C. -

Industry, ASCAP Agree Him As VP /GM at the San Diego Seattle, St

ISSUE NUMBER 646 THE INDUSTRY'S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER AUGUST 1, 1986 WARSHAW NEW KFSD VP /GM I N S I D E: RADIO BUSINESS Rosenberg Elevated SECTION DEBUTS To Lotus Exec. VP This week R &R expands the Transactions page into a two -page Radio Business section. This week and in coming weeks, you'll read: Features on owners, brokers, dealmakers, and more Analyses on trends in the ever -active station acquisition field Graphs and charts summarizing transaction data Financial data on the top broadcast players And the most complete and timely news available on station transactions. Hal Rosenberg Dick Warshaw Starts this week, Page 8 KFSD/San Diego Sr. VP/GM elevated to Exec. VP for Los Hal Rosenberg has been Angeles-based parent Lotus ARBITRON RATINGS RESULTS COMPROMISE REACHED Communications, which owns The spring Arbitrons for more top 14 other stations in California. markets continue to pour in, including Texas, Arizona, Nevada, Illi- this week figures for Houston, Atlanta, nois, and Maryland. Succeeding Industry, ASCAP Agree him as VP /GM at the San Diego Seattle, St. Louis, Kansas Cincinnati, Classical station is National City, Tampa, Phoenix, Denver, Miami, Sales Manager Dick Warshaw. and more. On 7.5% Rate Hike Rosenberg, who had been at Page 24 stallments, one due by the end After remaining deadlocked KFSD since it was acquired by Increases Vary of this year, and the other. by for several years, ASCAP and Lotus in 1974, assumes his new CD OR NOT CD: By Station next April. The new rates will the All- Industry Radio Music position January 1, 1987. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM