AMERICAN LOCAL RADIO JOURNALISM: a PUBLIC INTEREST CHANNEL in CRISIS by TYRONE SANDERS a DISSERTATION Presented to the Scho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synthesis of Txdot Uses of Real-Time Commercial Traffic Data

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/TX-12/0-6659-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date SYNTHESIS OF TXDOT USES OF REAL-TIME September 2011 COMMERCIAL TRAFFIC DATA Published: January 2012 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Dan Middleton, Rajat Rajbhandari, Robert Brydia, Praprut Report 0-6659-1 Songchitruksa, Edgar Kraus, Salvador Hernandez, Kelvin Cheu, Vichika Iragavarapu, and Shawn Turner 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas Transportation Institute The Texas A&M University System 11. Contract or Grant No. College Station, Texas 77843-3135 Project 0-6659 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Technical Report: Research and Technology Implementation Office September 2010–August 2011 P. O. Box 5080 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Austin, Texas 78763-5080 15. Supplementary Notes Project performed in cooperation with the Texas Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Project Title: Synthesis of TxDOT Uses of Real-Time Commercial Traffic Routing Data URL: http://tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-6659-1.pdf 16. Abstract Traditionally, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) and its districts have collected traffic operations data through a system of fixed-location traffic sensors, supplemented with probe vehicles using transponders where such tags are already being used primarily for tolling purposes and where their numbers are sufficient. In recent years, private providers of traffic data have entered the scene, offering traveler information such as speeds, travel time, delay, and incident information. -

Proposed Final Judgment: U.S. V. Entercom Communications Corp

Case 1:17-cv-02268 Document 2-1 Filed 11/01/17 Page 1 of 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, v. ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. and CBS CORPORATION, Defendants. PROPOSED FINAL JUDGMENT WHEREAS, Plaintiff, United States of America, filed its Complaint on November 1, 2017, the United States and defendants Entercom Communications Corp. and CBS Corporation, by their respective attorneys, have consented to the entry of this Final Judgment without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and without this Final Judgment constituting any evidence against or admission by any party regarding any issue of fact or law; AND WHEREAS, defendants agree to be bound by the provisions of this Final Judgment pending its approval by the Court; AND WHEREAS, the essence of this Final Judgment is the prompt and certain divestiture of certain rights or assets by the defendants to assure that competition is not substantially lessened; AND WHEREAS, the United States requires defendants to make certain divestitures for the purpose of remedying the loss of competition alleged in the Complaint; Case 1:17-cv-02268 Document 2-1 Filed 11/01/17 Page 2 of 20 AND WHEREAS, defendants have represented to the United States that the divestitures required below can and will be made, and that defendants will later raise no claim of hardship or difficulty as grounds for asking the Court to modify any of the divestiture provisions contained below; NOW THEREFORE, before any testimony is taken, without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and upon consent of the parties, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED: I. -

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

2004 Utah State Football

UTAH STATE FOOTBALL QUICK FACTS 2004 UTAH STATE FOOTBALL University Quick Facts Team Quick Facts Location: Logan, Utah 2003 Overall Record: 3-9 Founded: 1888 Sun Belt Conf. Record: 3-4 (tie 4th) Enrollment: 21,490 Basic Offense: One Back President: Dr. Kermit L. Hall (Akron, 1966) Basic Defense: 3-4 Director of Athletics: Randy Spetman (Air Force, 1976) Lettermen Returning: 43 (18 Off., 23 Def., 2 Spec.) Conference: Sun Belt Lettermen Lost: 24 (13 Off., 11 Def., 0 Spec.) Nickname: Aggies Returning Starters (2003 starts) Colors: Navy Blue and White Offense (4) Stadium: Romney Stadium (30,257) LT - Donald Penn (12) Turf: Sprinturf (installed summer of 2004) RT - Elliott Tupea (10) will play RG in 2004 WR - Raymond Hicks (7) Coaching Quick Facts QB - Travis Cox (12) Head Coach: Mick Dennehy (Montana, 1973) Defense (6) Record at USU: 16-29 (four years) NG - Ronald Tupea (12) Overall Record: 65-54 (11 years) RT - John Chick (9) will play LB in 2004 Linebackers -- Lance Anderson (Idaho State, 1996), 1st Year MLB - Robert Watts (12) Spec. Teams/Safeties -- Jeff Choate (W. Montana, 1993), 2nd Year WLB - Nate Fredrick (9) Off. Coord./QB -- Bob Cole (Widener, 1982), 5th Year LC - Cornelius Lamb (7) Offensive Line -- Jeff Hoover (UC Davis, 1991), 5th Year FS - Terrance Washington (8) Def. Coord. -- David Kotulski (N.M. State, 1975), 2nd Year Starters Lost (2003 starts) Tight Ends -- Mike Lynch (Montana, 1999), 3rd Year Offense (7) Defensive Line -- Tom McMahon (Carroll, 1992), 7th Year LG - Greg Vandermade (12) Secondary -- John Rushing (Wash. State, 1995), 2nd Year OC - Aric Galliano (12) Wide Receivers/Asst. -

The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 7 Number 2 Article 1 3-1-1987 Radio-Active Fallout and an Uneasy Truce - The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars Jonathan Michael Roldan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan Michael Roldan, Radio-Active Fallout and an Uneasy Truce - The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars, 7 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 217 (1987). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol7/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADIO-ACTIVE FALLOUT AND AN UNEASY TRUCE-THE AFTERMATH OF THE PORN ROCK WARS Jonathan Michael Roldan * "Temperatures rise inside my sugar walls." - Sheena Easton from the song "Sugar Walls."' "Tight action, rear traction so hot you blow me away... I want a piece of your action." - M6tley Criie from the album Shout at the Devil.2 "I'm a fairly with-it person, but this stuff is curling my hair." - Tipper Gore, parent.3 "Fundamentalist frogwash." - Frank Zappa, musician.4 I. OVERTURE TO CONFLICT It began as an innocent listening of Prince's award-winning album, "Purple Rain,"5 and climaxed with heated testimony before the Senate Committee on Commerce in September 1985.6 In the interim the phrase "cleaning up the air" took on new dimensions as one group of parents * B.A., Journalism/Political Science, Cal. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-210223-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/23/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000131574 Minor FM KLVJ 51503 Main 102.1 ENCINITAS, CA EDUCATIONAL 02/19/2021 Granted Modification MEDIA FOUNDATION From: To: 0000130766 Assignment LPD K36NB-D 187605 36 INCLINE VILLAGE MIRIAM MEDIA, INC. 02/19/2021 Granted of , NV Authorization From: MIRIAM MEDIA, INC. To: Gray Television Licensee, LLC 0000135321 License To FX K221FI 145577 92.1 MEXIA, TX TEMPLO DE DIOS, 02/19/2021 Granted Cover INC. 1 From: To: 0000130630 Transfer of FM KEHH 52897 Main 92.3 LIVINGSTON, TX Hope Media Group 02/19/2021 Granted Control From: Hope Media Group (Old Board) To: Hope Media Group (New Board) 0000130635 Transfer of FM KXBJ 36507 Main 96.9 EL CAMPO, TX Hope Media Group 02/19/2021 Granted Control From: Hope Media Group (Old Board) To: Hope Media Group (New Board) 0000130640 Transfer of FM KXNG 72685 Main 91.7 HOUSTON, TX Hope Media Group 02/19/2021 Granted Control From: Hope Media Group (Old Board) To: Hope Media Group (New Board) Page 1 of 10 REPORT NO. PN-2-210223-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/23/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

1 the Following Contest Is Intended for Participants in the United States

The following contest is intended for participants in the United States only and will be governed by United States laws. Do not proceed in this contest if you are not eligible or not currently located in the United States. Further eligibility restrictions are contained in the official rules below. FM 100.3 Christmas Concert Series 2020 OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE AN ENTRANT’S CHANCE OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED BY LAW. Contest Administrator: KSFI-FM, 55 North 300 West, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84180 Contest Sponsor: Shops at South Town, 10450 South State Street, Sandy, Utah 84070 1. HOW TO ENTER a. These rules govern the FM 100.3 Christmas Concert Series 2020 (“Contest”), which is being conducted by KSFI-FM (“Station”). The Contest begins on November 27, 2020 and ends on December 17, 2020 (“Contest Dates”). Entrants may enter via online only. b. To enter the Contest, entrant may enter online beginning on November 27, 2020 at 12:00 p.m. and ending on December 17, 2020 at 1:00 p.m. (“Entry Period”) as follows: i. To enter online, visit https://fm100.com/ , and follow the links and instructions to enter the Contest and complete and submit the online entry form during the Entry Period outlined above. Online entrants are subject to all notices posted online including but not limited to the Station’s Privacy Policy. Only one (1) entry per eligible person during the Entry Period regardless if entrant has more than one email address. -

99.7 Now / Kmvq-Fm Pay Your Bills

The following contest is intended for participants in the United States only and will be governed by United States laws. Do not proceed in this contest if you are not eligible or not currently located in the United States. Further eligibility restrictions are contained in the official rules below. 99.7 NOW / KMVQ-FM $5,000 SECRET SOUND OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE AN ENTRANT’S CHANCE OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED BY LAW. Contest Administrator/Sponsor: KMVQ-FM, 2001 Junipero Serra Blvd., Suite 350, Daly City, CA 94014 1. HOW TO ENTER a. These rules govern the 99.7 NOW $5,000 Secret Sound (“Contest”), which is being conducted by KMVQ-FM (“Station”). The Contest begins on Monday, September 20, 2021, and ends on Friday, November 5, 2021 (“Contest Dates”). Entrants may enter on-air only. KMVQ-FM may elect at its sole discretion, to continue the contest beyond this date if it so chooses. b. To enter the Contest, entrant may enter on-air beginning on Monday, September 20, 2021, at 9:20am (PT) “Pacific Time” and ending on Friday, November 5, 2021 at 5:20pm (PT) or after $40,000 has been awarded, whichever comes first (“Entry Period”). i. To enter on-air, listen to the Station each weekday beginning on Monday, September 20, 2021, at 9:20am (PT) and ending on Friday, November 5, 2021 at 5:20pm (PT) or after $40,000 has been awarded, whichever comes first during the Entry Period for the air personality to announce the cue to call. -

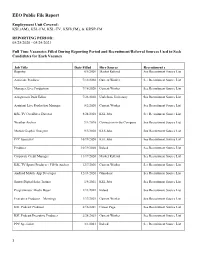

EEO-Public-File-Report-2020-2021

EEO Public File Report Employment Unit Covered: KSL(AM), KSL-FM, KSL-TV, KSFI(FM), & KRSP-FM REPORTING PERIOD: 05/25/2020 - 05/24/2021 Full Time Vacancies Filled During Reporting Period and Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy Job Title Date Filled Hire Source Recruitment s Reporter 6/5/2020 Market Referral See Recruitment Source List Associate Producer 7/12/2020 Current Worker See Recruitment Source List Manager, Live Production 7/16/2020 Current Worker See Recruitment Source List Assignment Desk Editor 7/23/2020 Utah State University See Recruitment Source List Assistant Live Production Manager 8/2/2020 Current Worker See Recruitment Source List KSL TV OverDrive Director 8/24/2020 KSL Jobs See Recruitment Source List Weather Anchor 9/1/2020 Connection in the Company See Recruitment Source List Motion Graphic Designer 9/3/2020 KLS Jobs See Recruitment Source List PPC Specialist 10/19/2020 KSL Jobs See Recruitment Source List Producer 10/19/2020 Indeed See Recruitment Source List Corporate Credit Manager 11/17/2020 Market Referral See Recruitment Source List KSL TV Sports Producer / Fill-In Anchor 12/7/2020 Current Worker See Recruitment Source List Android Mobile App Developer 12/14/2020 Glassdoor See Recruitment Source List Senior Digital Sales Trainer 1/4/2021 KSL Jobs See Recruitment Source List Programmatic Media Buyer 1/11/2021 Indeed See Recruitment Source List Executive Producer – Mornings 1/17/2021 Current Worker See Recruitment Source List KSL Podcast Producer 2/16/2021 Career Page See Recruitment -

Another Death Takes Sikkim's COVID Toll to 79

KATE MIDDLETON AND GABRIELLA BROOKS AND GHANA’S POLITICS HAS STRONG LIAM HEMSWORTH COZY UP PRINCE WILLIAM TAKE PART TIES WITH PERFORMING ARTS. IN SOCIALLY DISTANCED AS THEY CELEBRATE LUKE THIS IS HOW IT STARTED HEMSWORTH'S BIRTHDAY REMEMBRANCE SUNDAY EVENT 04 pg 08 pg 08 Vol 05 | Issue 294 | Gangtok | Tuesday | 10 November 2020 RNI No. SIKENG/2016/69420 Pages 8 | ` 5 SDF MOURNS SANCHAMAN LIMBOO’S PASSING AWAY Chamling remembers Sanchaman Another death takes Limboo as “vocal, bold and truthful” SUMMIT REPORT tant portfolios in Health former Chief Minister but Gangtok, 09 Nov: and Education as a cabi- also of a great human be- ikkim Democratic net minister,” Mr Cham- ing. On a personal level, Sikkim’s COVID toll to 79 SFront party president, ling writes. I feel the loss as if it was SUMMIT REPORT Chief Minister Pawan Mr Chamling high- my own family member,” Gangtok, 09 Nov: Chamling, has condoled lights that the late Mr ikkim recorded one the demise of Sancha- Limboo was a “vocal, The Sikkim Demo- Smore COVID-19 relat- man Limboo, the fourth bold, truthful and ex- craticMr Chamling Front alsoconfides. held a ed death with the pass- Chief Minister of Sikkim. tremely sincere politi- condolence meeting on ing away of an 80-year- Mr Limboo was also a se- cian who had no guile or Monday in the memory old woman from Chiso- nior member of the SDF malice.” of former Chief Minister, pani in South District on and has served as Deputy “He spoke for causes Sanchaman Limboo, here Sunday. -

Bonneville International V. Utah State Tax Commission : Brief of Petitioner Utah Court of Appeals

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Court of Appeals Briefs 1992 Bonneville International v. Utah State Tax Commission : Brief of Petitioner Utah Court of Appeals Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca1 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Court of Appeals; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. Brian L. Tarbet; Assistant Attorney General; Attorney for Respondent. Boyd J. Hawkins; Brian C Johnson; Scott R. Ryther; Kimball, Parr, Waddoups, Brown & Gee; Attorneys for Petitioners. Recommended Citation Legal Brief, Bonneville International v. Utah State Tax Commission, No. 920775 (Utah Court of Appeals, 1992). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca1/4781 This Legal Brief is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Court of Appeals Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. JTAH DOCUMENT CFU iO A10 )OCKET NO. <&(m*Ck IN THE UTAH COURT OF APPEALS BONNEVILLE INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION, y £i\j m 5 <c O//J-CA vs. Priority UTAH STATE XAA COMMISSION, Respondent. BRIEF OF PETITIONER Petition for Review of the Final Order of the Utah State Tax Commission Brian L. Tarbet, Esq. Boyd J. Hawkins, Esq. (A5201) Assistant Attorney General Assistant General Counsel 36 South State Street Bonneville International Corporation Eleventh Floor Broadcast House Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 55 North Third West P.O. -

Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Media Studies College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/ms Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kidd, D. (2005). Clear channel and the public airwaves. In E. Cohen (Ed.), News incorporated (pp. 267-285). New York: Prometheus Books. Copyright © 2005 by Elliot D. Cohen. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 13 CLEAR CHANNEL AND THE PUBLIC AIRWAVES DOROTHY KIDD UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO With research assistance from Francisco McGee and Danielle Fairbairn Department of Media Studies, University of San Francisco DOROTHY KIDD, a professor of media studies at the University of San Francisco, has worked extensively in community radio and television. In 2002 Project Censored voted her article "Legal Project to Challenge Media Monopoly " No. 1 on its Top 25 Censored News Stories list. Pub lishing widely in the area of community media, her research has focused on the emerging media democracy movement. INTRODUCTION or a company with close ties to the Bush family, and a Wal-mart-like F approach to culture, Clear Channel Communications has provided a surprising boost to the latest wave of a US media democratization movement.