How Dawkins Got Pwned (Part 1) Richard Dawkins Recently Wrote a Book Called the God Delusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The God Delusion Debate . Discussion Guide

The God Delusion Debate . Discussion Guide . 1 THE GOD DELUSION DEBATE A DISCUSSION GUIDE compiled by Bill Wortman We take ideas seriously THE PARTICIPANTS Richard Dawkins, FRS at the time of this debate held the posi- tion of Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Oxford. He did his doctorate at Oxford under Nobel Prize winning zoologist, Niko Tinbergen. He is the author of nine books, some of which are !e Sel"sh Gene (1976, 2nd edition 1989), !e Blind Watchmaker (1986), !e God Delu- sion (2006), and most recently !e Greatest Show on Earth (2009). Dawkins is an atheist. John Lennox is a Reader in Mathematics at the University of Oxford and Fellow in Mathematics and Philosophy of Science at Green College, University of Oxford. He holds doctorates from Oxford (D. Phil.), Cambridge (Ph.D.), and the University of Wales (D.Sc.) and an MA in Bioethics from the University of Surrey. In addition to authoring over seventy peer reviewed papers in pure mathematics, and co-authoring two research monographs for Ox- ford University Press, Dr. Lennox is the author of God’s Undertaker: Has Science Buried God? (2007). Lennox is a Christian. Larry A. Taunton is founder and Executive Director of Fixed Point Foundation and Latimer House. Like Fixed Point itself, Larry specializes in addressing issues of faith and culture. A published author, he is the recipient of numerous awards and research grants. He is Executive Producer of the !lms “Science and the God Ques- tion” (2007), “"e God Delusion Debate” (2007), “God on Trial” (2008), “Has Science Buried God?” (2008), “Can Atheism Save Eu- rope?” (2009), and “Is God Great?” (2009). -

Atheism AO2 Handout Part 1

Philosophy Of Religion / Atheism AO2 Atheism AO2 Handout Part 1 New Atheism successfully shows the incompatibility of science and religion. Evaluate this view. 1. New Atheists seem to argue that scientific theories are based only on evidence, whilst religion runs away from evidence. The claim is that atheism is rational and scientific while religion is irrational and superstitious. Faith is not an element of science since evidence for a correct conviction compels us to accept its truth. As Dawkins says “Faith is a state of mind that leads people to believe something – it doesn’t matter what – in the total absence of supporting evidence. If there were good supporting evidence, then faith would be superfluous…” However, Alister McGrath points out that such a view “fails to make the critical distinction between the ‘total absence of supporting evidence’ and the ‘absence of totally supporting evidence’.” It is true that some facts about the world have been proved (e.g. the chemical formula for water) but the bigger scientific questions such as is there a Grand Unified Theory that explains everything rely on answers based on the best evidence available but they are not certainties. In future years they may well change as new evidence is considered. As Gauch concluded “Science rests on faith”. Dawkins in his book “The God Delusion” does argue that the existence of God is a testable hypothesis and concludes that the hypothesis is falsifiable. Therefore the hypothesis is open to the scientific method. So here is a New Atheist proponent arguing that that the existence of God is a meaningful hypothesis. -

Christianity, Islam & Atheism

Christianity, Islam & Atheism Reflections on Religion, Society & Politics Michael Cooke 2 Christianity, Islam & Atheism About the author Michael Colin Cooke is a retired public servant and trade union activist who has a lifelong interest in South Asian history, politics and culture. He has served as an election monitor in Sri Lanka. Michael is the author of The Lionel Bopage Story: Rebellion, Repression and the Struggle for Justice in Sri Lanka (2011). He has also penned when the occasion demanded a number of articles and film reviews. He lives in Melbourne. Published 2014 ISBN 978-1-876646-15-8 Resistance Books: resistancebooks.com Contents 1.Genesis............................................................................................5 2.The Evolution of a Young Atheist .............................................13 India...................................................................................................................... 13 Living in the ’70s down under.............................................................................. 16 Religious fundamentalism rears its head............................................................. 20 3.Christianity: An Atheist’s Homily ................................................21 Introduction – the paradox that is Christianity................................................... 21 The argument....................................................................................................... 23 It ain’t necessarily so: Part 1................................................................................ -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Liberty Magazine January 1995.Pdf Mime Type

The Bell Curve, Stupidity, and January 1995 Vol. 8, No.3 $4.00 You ~ ,.';.\, . ~00 . c Libertarian Bestsellers autographed by their authors - the ideal holiday gift! Investment Biker The story of a legendary Wall Street investor's·travels around the world by motorcycle, searching out new investments and adventures. "One of the most broadly appealing libertarian books ever published." -R.W. Bradford, LffiERTY ... autographed by the author, Jim Rogers. (402 pp.) $25.00 hard cover. Crisis Investing for the Rest of the '90s This perceptive classic updated for today's investor! "Creative metaphors; hilarious, pithy anecdotes; innovative graphic analyses." -Victor Niederhoffer, LffiERTY ... autographed by the author, Douglas Casey. (444 pp.) $22.50 hard cover. It Carne froIn Arkansas David Boaz, Karl Hess, Douglas Casey, Randal O'Toole, Harry Browne, Durk Pearson, Sandy Shaw, and others skewer the Clinton administration ... autographed by the editor, R.W. Bradford. (180 pp.) $12.95 soft cover. We the Living (First Russian Edition) Ayn Rand's classic novel ofRussia translated into Russian. A collector's item ... autographed by the translator, Dimitry Costygin. (542 pp.) $19.95 hard cover. The God of the Machine Isabel Paterson's classic defense of freedom, with a new introduction by Stephen Cox. Autographed by the editor. (366 pp.) $21.95 soft cover. Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic A mind-bending meditation on the new revolution in computer intelligence - and on the nature of science, philosophy, and reality ... autographed by the author, Bart Kosko. (318 pp.) $12.95 soft cover. Freedorn of Informed Choice: The FDA vs Nutrient Supplements A well-informed expose of America's pharmaceutical "fearocracy." The authors' "'split label' proposal makes great r----------------------------,sense." -Milton Friedman .. -

Christian Formation: Where Do We Start? Fulfilling the Promise of Newman's Second Spring a Synthetic Universe Same-Sex Marriag

January and February 2012 “ Pullout” Volume 44 Number 1 Price £4.50 faithPROMOTING A NEW SYNTHESIS OF FAITH AND REASON Christian Formation: Where Do We Start? Editorial Fulfilling the Promise of Newman’s Second Spring James Tolhurst A Synthetic Universe Edward Holloway Same-sex Marriage and an Uncertain Church Niall Gooch Also William Oddie on varied Catholic responses to homosexual “rights” Dylan James responds to correspondence on the purpose of sex Johann Christian Arnold on singleness and union Robert Colquhoun on a guide to purity Brendan MacCarthy and Peter Mitchell on pro-life practice And Reviews of two responses to the New Atheism www.faith.org.uk A special series of pamphlets REASONS FOR BELIEVING from Faith Movement Straightforward, up to date and well argued pamphlets on basic issues of Catholic belief, this new series will build into a single, coherent apologetic vision of the Christian Mystery. They bring out the inner coherence of Christian doctrine and show how God’s revelation makes sense of our own nature and of our world. Five excellent pamphlets in the series are now in print. Can we be sure God exists? What makes Man unique? The Disaster of Sin Jesus Christ Our Saviour Jesus Christ Our Redeemer NEW The Church: Christ’s Voice to the World To order please write to Sr Roseann Reddy, Faith-Keyway Trust Publications Office, 104 Albert Road, Glasgow G42 8DR or go to www.faith.org.uk Catholicism a New Synthesis faith summer by Edward Holloway conference Pope John Paul II gave the blueprint for catechetical renewal with the Catechism of the Catholic Church. -

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy , Claire Elizabeth Harris Department of Politics, University of Sheffield September 2005 Acknowledgements There are so many people I'd like to thank for helping me through the roller-coaster experience of academic research and thesis submission. Firstly, without funding from the ESRC, this research would not have taken place. I'd like to say thank you to them for placing their faith in my research proposal. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Andrew Taylor. Without his good humour, sound advice and constant support and encouragement I would not have reached the point of completion. Having a supervisor who is always ready and willing to offer advice or just chat about the progression of the thesis is such a source of support. Thank you too, to Andrew Gamble, whose comments on the final draft proved invaluable. I'd also like to thank Pat Seyd, whose supervision in the first half of the research process ensured I continued to the second half, his advice, experience and support guided me through the challenges of research. I'd like to say thank you to all three of the above who made the change of supervisors as smooth as it could have been. I cannot easily put into words the huge effect Sarah Cooke had on my experience of academic research. From the beginnings of ESRC application to the final frantic submission process, Sarah was always there for me to pester for help and advice. -

Libertarian Party at Sea on Land

Libertarian Party at Sea on Land To Mom who taught me the Golden Rule and Henry George 121 years ahead of his time and still counting Libertarian Party at Sea on Land Author: Harold Kyriazi Book ISBN: 978-1-952489-02-0 First Published 2000 Robert Schalkenbach Foundation Official Publishers of the works of Henry George The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation (RSF) is a private operating foundation, founded in 1925, to promote public awareness of the social philosophy and economic reforms advocated by famed 19th century thinker and activist, Henry George. Today, RSF remains true to its founding doctrine, and through efforts focused on education, communities, outreach, and publishing, works to create a world in which all people are afforded the basic necessities of life and the natural world is protected for generations to come. ROBERT SCHALKENBACH FOUND ATION Robert Schalkenbach Foundation [email protected] www.schalkenbach.org Libertarian Party at Sea on Land By Harold Kyriazi ROBERT SCHALKENBACH FOUNDATION New York City 2020 Acknowledgments Dan Sullivan, my longtime fellow Pittsburgher and geo-libertarian, not only introduced me to this subject about seven years ago, but has been a wonderful teacher and tireless consultant over the years since then. I’m deeply indebted to him, and appreciative of his steadfast efforts to enlighten his fellow libertarians here in Pittsburgh and elsewhere. Robin Robertson, a fellow geo-libertarian whom I met at the 1999 Council of Georgist Organizations Conference, gave me detailed constructive criticism on an early draft, brought Ayn Rand’s essay on the broadcast spectrum to my attention, helped conceive the cover illustration, and helped in other ways too numerous to mention. -

Memeplex Summary

Summary of Content for Essay ‘The Memeplex of CAGW’ : (find the essay here) Foreword Essentially a repeat of the above pointer-post text. 1) Introduction. (~900 words) The short introduction punts out to the Internet and Appendices regarding background material on memes and the definition of a memeplex, plus other terms / concepts in memetics. It then moves on to an initial look at the very many comparisons in blogs and articles of CAGW with religion, which arise because both are memetically driven. 2) Religious memeplexes. (~1200 words) Religions are a class of memeplexes that have long been studied by memeticists. A list of 12 characteristics of religions is briefly examined regarding commonality with CAGW. To understand the similarities and differences, we have to know more about what a memeplex is and what it does. The section provides tasters regarding explanation at the widest scope, before moving on to the rest of the essay for detail. 3) Collective-personal duality. (~3500 words) This section and the following two provide a first-pass characterization of memeplexes. The most perplexing area is covered first, that of a memeplex as an ‘entity’ and its constraints upon the free will and action of its adherents. Introduces the collective-personal duality model and a symbiotic relationship with interlocking collective and personal elements. Uses this to enlighten regarding both the religious list above and CAGW, especially on self-identification with the memeplex, and cites circumstantial evidence including the actions of Peter Gleick and Michael Tobis. Looks at the fractious peace between the Christian and CAGW memeplexes. Backs the collective-personal duality model via the concept of The Social Mind from neuroscientist Michael S. -

Our Enemy, the State

Our Enemy, The State by Albert J. Nock - 1935 His Classic Critique Distinguishing 'Government' from the 'STATE'. In Memoriam Albert Jay Nock 1870 - 1945 In Memoriam Edmund Cadwalader Evans A sound economist, one of the few who understand the nature of the state Be it or be it not true that Man is shapen in iniquity and conceived in sin, it is unquestionably true that Government is begotten of aggression, and by aggression. -- Herbert Spencer, 1850. This is the gravest danger that today threatens civilization: State intervention, the absorption of all spontaneous social effort by the State; that is to say, of spontaneous historical action, which in the long-run sustains, nourishes and impels human destinies. -- Jose Ortega y Gasset, 1922. It [the State] has taken on a vast mass of new duties and responsibilities; it has spread out its powers until they penetrate to every act of the citizen, however secret; it has begun to throw around its operations the high dignity and impeccability of a State religion; its agents become a separate and superior caste, with authority to bind and loose, and their thumbs in every pot. But it still remains, as it was in the beginning, the common enemy of all well-disposed, industrious and decent men. -- Henry L. Mencken, 1926. PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION When OUR ENEMY, THE STATE appeared in 1935, its literary merit rather than its philosophic content attracted attention to it. The times were not ripe for an acceptance of its predictions, still less for the argument on which these predictions were based. -

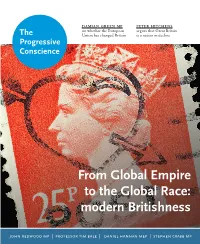

Peter Hitchens on Whether the European Argues That Great Britain the Union Has Changed Britain Is a Nation in Decline Progressive Conscience

DAMIAN GREEN MP PETER HITCHENS on whether the European argues that Great Britain The Union has changed Britain is a nation in decline Progressive Conscience From Global Empire to the Global Race: modern Britishness john redwood mp | professor tim bale | daniel hannan mep | stephen crabb mp Contents 03 Editor’s introduction 18 Daniel Hannan: To define Contributors James Brenton Britain, look to its institutions PROF TIM BALE holds the Chair James Brenton politics in Politics at Queen Mary 20 Is Britain still Great? University of London 04 Director’s note JAMES BRENTON is the editor of Peter Hitchens and Ryan Shorthouse Ryan Shorthouse The Progressive Conscience 23 Painting a picture of Britain NICK CATER is Director of 05 Why I’m a Bright Blue MP the Menzies Research Centre Alan Davey George Freeman MP in Australia 24 What’s the problem with STEPHEN CRABB MP is Secretary 06 Replastering the cracks in the North of State for Wales promoting British values? Professor Tim Bale ROSS CYPHER-BURLEY was Michael Hand Spokesman to the British 07 Time for an English parliament Embassy in Tel Aviv 25 Multiple loyalties are easy John Redwood MP ALAN DAVEY is the departing Damian Green MP Arts Council Chief Executive 08 Britain after the referendum WILL EMKES is a writer 26 Influence in the Middle East Rupert Myers GEORGE FREEMAN MP is the Ross Cypher-Burley Minister for Life Sciences 09 Patriotism and Wales DR ROBERT FORD lectures at 27 Winning friends in India Stephen Crabb MP the University of Manchester Emran Mian DAMIAN GREEN MP is the 10 Unionism