Maternal Health and Maternal Mortality: a Study of Four Selected Districts of Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notification: Half Yearly Departmental Examination-2015

ASSAM PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Jawaharnagar, Khanapara, Guwahati-781 022 No. 30PSC/E-4/2015-2016 Dated Guwahati the 1st February/2016 NOTIFICATION In continuation of this office Notification No.3PSC/E-4/2015-2016 Dated 23-11-2016, the programme of the next Half-Yearly Departmental Examination is notified as below. A list showing the name of officers with Roll Numbers against each candidate will be displayed outside the Examination Hall at the following centres on the day of examination. Moreover, the list may be downloaded from APSC website www.apsc.nic.in w.e.f. 10-02-2016. The names of candidates whose applications have been rejected are also shown in a separate list in the aforesaid website. Guwahati Centre APSC Office Building , Khanapara, Ghy. -22. Jorhat Centre Jorhat Govt. Boy’s H.S & M.P. School, Jorhat Tezpur Centre Rastrab has ha Vidyalaya , Near Polo Field, Tezpur Silchar Centre Govt. Girls H.S & M.P. School, Silchar Shillong Cen tre O/o. the Meghalaya P.S.C., Horse Shoe Building, Lower Lachumiaere, Shillong, Meghalaya. PROGRAMME OF EXAMINATION 26 TH FEBRUARY, 2016 (FRIDAY) TIME: 9.00 AM TO 12.00 NOON 1. ACCOUNTS (FIRST PAPER) WITHOUT BOOKS FOR IAS, ETC. OFFICERS 2. REGISTRATION RULES ETC. FOR SUB-REGISTRAR 3. POLICE LAW (WITH BOOKS) FOR POLICE OFFICERS 4. LAW PART-I (WITHOUT BOOKS) FOR COOPERATIVE OFFICERS. 5. ACCOUNTS (WITH BOOKS) FOR EXCISE OFFICERS. 6. GENERAL LAW PAPER-I (WITHOUT BOOKS) FOR LABOUR OFFICERS 7. LAW PAPER (WITH BOOKS) FOR OFFICERS OF LEGAL METROLOGY. TIME: 1.00 PM TO 4.00 PM 1. -

Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal Para)

CHAPTER- III Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal para) Erstwhile Goalpara district of Western Assam has a unique socio-cultural heritage of its own, identified as Goalpariya Society and Culture. The society is a heterogenic in character, composed of diverse racial, ethnic, religious and cultural groups. The medieval society that had developed in Western Assam, particularly in Goalapra region was seriously influenced by the induction of new social elements during the British Rule. It caused the reshaping of the society to a fully heterogenic in character with distinctly emergence of new cultural heritage, inconsequence of the fusion of the diverse elements. Zamindars of Western Assam, as an important social group, played a very important role in the development of new society and cufture. In the course of their zamindary rule, they brought Bengali Hidus from West Bengal for employment in zamindary service, Muslim agricultural labourers from East Bengal for extension of agricultural field, and other Hindusthani people for the purpose of military and other services. Most of them were allowed to settle in their respective estates, resulting in the increase of the population in their estate as well as in Assam. Besides, most of the zamindars entered in the matrimonial relations with the land lords of Bengal. As a result, we find great influence of the Bengali language and culture on this region. In the subsequent year, Bengali cultivators, business community of Bengal and Punjab and workers and labourers from other parts of Indian subcontinent, migrated in large number to Assam and settled down in different places including town, Bazar and waste land and char areas. -

Hand Book V-II (3).Pdf

You are requested to give effect to such concession as usual, and you are also requested to indicate the caste of the applicant(s) while stibmitting proposals to the Government for Settlement of land or conversion of A. P. lands into periodic Pattas as necessary, so that the concession as stated above may be extended to the persons of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Yours faithfully, Sd/-D. K. GANGOPADHYAY, Commissioner & Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Revenue (S) Department, Dispur. Memo No. RSD. 8/87/47-A Dt. Dispur, the 3rd May, 1990 Copy forwarded to :– (1) The Chairman, Assam Board of Revenue, Guwahati-I. (2) The Commissioner, W. P. T. & B. C. Department, Dispur. (3) The Commissioner of Division & B. C. Department, Dispur. (4) The Director of Land Records, Assam, Bamunimaidan, Ghy-21. (5) The Director of Land Requisition, Acquisition & Reforms, Assam Guwahati-l . (6) The Principal, Assam Survey & Settlement Training Centre, Dakhingaon, Guwahati-28. (7) Guard File. By Order etc., Sd/-D. K. GANGOPADHYAY, Commissioner & Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Revenue (S) Department, Dispur. (121) GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM REVENUE (SETTLEMENT) DEPARTMENT SETTLEMENT BRANCH No. RSD. 8/87/49 Dated Dispur, the 10th May, 1990 From : Shri D. K. Gangopadhyay, IAS, Commissioner & Secretary to the Government of Assam. To The Deputy Commissioner ________________________ The Settlement Officer ________________________ The Sub-Divisional Officer ________________________ (Except Karbi Anglong & N. C. Hills Districts) Sub. : Preservation of PGRs/VGRs and other reservation for public purposes and ecological balance. Sir, You are aware perhaps that the Government have emphasised on preserving the existing PGRs and VGRs in the State for use by the public for the purpose for which the reserves have been constituted and removal of the encroachments on the PGRs and VGRs as per Settlement Rules 18(2) and Section 165 under the Chapter X of the ALRR 1886 (amended) in time and without delay. -

Notification

ASSAM PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION **** ADVT. NO.17/2016 No.3PSC/E-8/2016-17 Dated Guwahati, the 1st November /2016. NOTIFICATION It is hereby notified for information to all concerned Officers that the next Half Yearly Departmental Examination will be conducted by the Commission at Guwahati / Jorhat / Tezpur/ Silchar & Shillong. The Dates, Venues and Programme of the examination will be notified later on. As per Govt. letter communicated vide Memo No. HMA.46/2010/235-A, dated 13th October/2011, Officers in the rank of Inspector of Police are not permitted to appear in the Half Yearly Departmental Examination conducted by the Commission for IAS/IPS/ACS/APS etc. Officers till they are promoted to APS Junior Grade. Non-Gazetted Police Officer will appear at the examination to be held at the Headquarter of the District in which they are serving under supervision of a separate local Examination Board in each District, which shall be conducted simultaneously with the examination on Police Law and Languages of the Half Yearly Departmental Examination. The Officers who intend to appear at the Examination to be conducted by the Commission should download the Prescribed Form, viz: “Application Form for Half Yearly Departmental Examination,2016” from the Commission’s website www.apsc.nic.in and submit the filled in Application Form to the Secretary, Assam Public Service Commission, Jawaharnagar, Khanapara, Guwahati-22 through Deputy Commissioners, SDOs with intimation to the Govt. in the Personnel (A) Deptt. in case of IAS & ACS Officers and through their District/Sub- Divisional Heads under intimation to their Administrative Deptt. -

Special Reference to Anubadar Katha by Krishna Kanta Handique)

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Relevance of translation (Special reference to Anubadar Katha by Krishna Kanta Handique) Jyotsna Devi Research scholar Gauhati University Abstract: Krishna Kanta Handique is a helmsman of modern Assamese language who has contributed to the granary of Assamese literature with writings and criticism on Western language and literature. He has also done a great amount of translation from Sanskrit and other European languages. Krishna Kanta Handique analyses various issues and aspects of literature in his original writings. Anubadar Katha by Krishna Kanta Handique is an essay associated to the issues of translation. In this article, he has analysed the role of translation to make a language and literature enrich with certain instances. He also talks about the relevance of translation in Assamese literature too. The objective of the paper is to analyse relevance of translation discussed by Krishna Kanta Handique in his Anubadar Katha Key words: Assamese literature, Krishna Kanta Handique, relevance, translation. Introduction Krishna Kanta Handique was one of the most renowned figures of modern Assamese literature whose contribution to Assamese literature is immense. He is a helmsman of Assamese language and literature with the knowledge of thirteen languages including Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, Russian, Italian, Spanish, Pali etc. Apart from the translation of ancient epical writings such as Yashastilak, Naishadh-Charita, Krishna Kanta Handique has enriched the literary field with his critical writings. Moreover, he has also contributed to the granary of Assamese literature with poems, paintings, philosophy, children literature, biographical writings and criticism on Western language and literature. -

Chapter Four Assam: the Land of Opportunities Assam, the Land of Opportunities

Chapter Four Assam: The land of Opportunities The present study has been conducted in the state of Assam. Assam state is known for its breath taking scenic beauty, rarest flora and fauna, lofty green hills, vast rolling plain, mighty waterways, exotic animals, migratory birds, AHOM architectures and a land of fairs and festivals. In ancient times Assam constituted a part of the land known successively as Pragjyotishpura, and Kamrup. Opinions on the root of the name vary with one view ascribing its origin to the Bodo word Ha-Cham which means “low or level country” and a second view ascribing it to the word Asama, meaning “unequalled” or “peerless”, and used to denote the Ahoms, a Shan tribe which ruled the land for six centuries from the 13th Century A.D. Assam is known for Assam tea, petroleum resources, Assam Silk and for its rich biodiversity. It has successfully conserved the one-horned Indian rhinoceros from near extinction in Kaziranga, the tiger in Manas and provides one of the last wild habitats for the Asian elephant. (Kumar& Singh: 2011). It is increasingly becoming a popular destination for wild life tourism. Assam is also known for its Sal tree forests and forest products, much depleted now. A land of high rainfall, Assam is endowed with lush greenery and the mighty river Brahmaputra, whose tributaries and oxbow lakes provide the region with a unique hydro- geomorphic and aesthetic environment. Assam, the land of opportunities Assam, the land of opportunities, is lying between the latitudes 24 degree N to 28 degree and longitudes 90 degree to 96 degree East longitude and is situated in the north east corner of India. -

North Eastern Region NW-2 National Waterway 2 NSDP Net State Domestic Product

Development and Growth in Northeast India The Natural Resources Water and Environment Nexus Strategy Report Strategy Report DEVELOPMENT AND GROWTH IN NORTHEAST INDIA The Natural Resources, Water, and Environment Nexus Report No. 36397-IN Development and Growth in Northeast India The Natural Resources, Water, and Environment Nexus Strategy Report June 2007 South Asia Region Sustainable Development Department Environment & Water Resource Management Unit Document of the World Bank © 2007 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 First published, 2007 Produced by: Roots Advertising Services Pvt Ltd B-4/26, Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi - 110029, India Tel.: 26166493, 26104751 Fax: 26178688 E-mail: [email protected] Photo Credits: Biswasjyoti Das and Karin Kemper Printed at: PS Press Services Pvt. Ltd., India The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The report has been discussed with the Government of India, but does not necessarily bear their approval for all its contents, especially where the authors have stated their judgements/opinions/policy recommendations. This report has received funding from the UK Department for International Development, although the views expressed within do not necessarily reflect their official policy. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. -

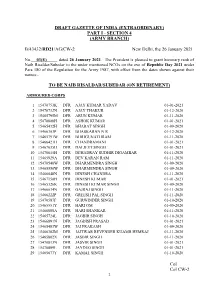

Col Col CW-2 DRAFT GAZETTE of INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I

DRAFT GAZETTE OF INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I - SECTION 4 (ARMY BRANCH) B/43432/RD21/AG/CW-2 New Delhi, the 26 January 2021 No. 03(E) dated 26 January 2021. The President is pleased to grant honorary rank of Naib Risaldar/Subedar to the under mentioned NCOs on the eve of Republic Day 2021 under Para 180 of the Regulation for the Army 1987, with effect from the dates shown against their names:- TO BE NAIB RISALDAR/SUBEDAR (ON RETIREMENT) ARMOURED CORPS 1 15470753K DFR AJAY KUMAR YADAV 01-01-2021 2 15470732N DFR AJAY THAKUR 01-12-2020 3 15465795M DFR ARUN KUMAR 01-11-2020 4 15470808H DFR ASHOK KUMAR 01-01-2021 5 15465432H DFR BHARAT SINGH 01-09-2020 6 15466303P DFR BHASKARAN N R 01-12-2020 7 15465791W DFR BHRIGUNATHRAM 01-11-2020 8 15466421H DFR CHANDRAMANI 01-01-2021 9 15467035H DFR DALJEET SINGH 01-01-2021 10 15470615H DFR DEHADRAY SUDHIR DIGAMBAR 01-11-2020 11 15465929A DFR DEV KARAN RAM 01-11-2020 12 15470540W DFR DHARMENDRA SINGH 01-09-2020 13 15465550W DFR DHARMENDRA SINGH 01-09-2020 14 15466048N DFR DINESH CHANDRA 01-11-2020 15 15467150H DFR DINESH KUMAR 01-01-2021 16 15465326K DFR DINESH KUMAR SINGH 01-09-2020 17 15466034N DFR GAJRAJ SINGH 01-11-2020 18 15466222P DFR GREESH PAL SINGH 01-11-2020 19 15470587F DFR GURWINDER SINGH 01-10-2020 20 15465551Y DFR HARI OM 01-09-2020 21 15466000A DFR HARI SHANKAR 01-11-2020 22 15465724L DFR JAGBIR SINGH 01-10-2020 23 15466891N DFR JAGDISH PRASAD 01-01-2021 24 15465483W DFR JAI PRAKASH 01-09-2020 25 15466302M DFR JAITWAR REVENDER KUAMR HEMRAJ 01-11-2020 26 15465802X DFR JASBIR SINGH 01-11-2020 -

Government of Assam Office of the Deputy Commissioner Barpeta (Transformation & Development Branch)

Page l1 GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER BARPETA (TRANSFORMATION & DEVELOPMENT BRANCH) MINUTES OF DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE MEETING HELD ON 06-09-2019 AT 11-00 AM IN THE CONFERENCE HALL OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER'S OFFICE BARPETA 'fhe list ofofficers present is enclosed at Annexure-l . The meeting was presided over by Sri Munindra Sarma ACS, Deputy Commissioner, Barpeta. Welcorning all the officer's present DC initiated sector wise discussion with regards to progress of different schemes as follows: 1. Water Resource:- The meeting reviewed the progress of different schemes taken up by the water Resource deptt. through power point presentation. The Executive Engineer, Water Resource department informed that during 2017 -18, a total of 4 (four) Nos. of schemes and during 20 l 8- 19, a total of l0 (ten) Nos. of schemes have been taken up under SDRF all of which are nearing completion and expected to be completed by Oct.l20l9. He also informed about 4 Nos. of ongoing schemes under NABARD (RIDF) with a likely date of completion by 3111012019. The Deputy Commissioner, Barpeta asked the Ex. Engineer to ensure completion all the works within the time stipulated. DC asked the officer to submit a letter to the concerned Circle Officers with a copy to DC, Barpeta to resolve the issues relating to demarcation of land as some of the SOPD schemes could not be rolled out in time In a query from the Chairman, Ex. Engineer, Water Resource division informed that rising of bed level of Beki River and other tributaries is the main cause of the Highest flood level this year after 2004 with devastation of many embankments in the district. -

Training Report for the Month of October 2016

TRAINING REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF OCTOBER 2016 Training activities on Disaster Management (October, 2016 Report) Disaster Management is an area where people with necessary skills and expertise to carry the risk of facilitating disasters rather than prevent, mitigate or respond to them effectively. Therefore “Training” is an important component of the Disaster management system. It facilitates the strengthening of response mechanism as well as empowers all the stakeholders to take appropriate preparedness measures. The Community Based Disaster Preparedness (CBDP) training module is designed so as to prepare the community level volunteers/ organizations to deal with an emergency situation that may arise due to different hazards. The course provides the opportunity to learn essential knowledge and skills in disaster and to address implementation challenges in a systematic manner. The participants are provided with practical tools for design and implementation of programs for disaster preparedness through community capacity to promote a culture of safety. The NGO volunteers, CBO, Mahila Samittees, Gram Sevak, Self Help Groups, Anganwadi, ASHA etc. are targeted to be trained in CBDP. The Training on Public Health in Emergencies (PHE) is aimed at giving specialised guidance in public health promotion and protection, disease prevention, health assessment and disease surveillance during an emergency. State, local and block level Public Health Engineering officials; Health; and Social Welfare Department officials working in various sectors of sanitation & hygiene promotion are usually targeted as they are the immediate responders to these situations and they should have immediate access to guidance and information that will assist them in rapidly establishing priorities of undertaking necessary actions during the response to an emergency or disaster besides being duly prepared if any such calamity strikes. -

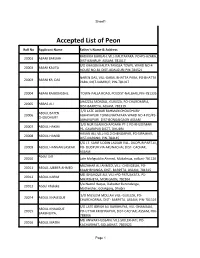

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

List of Stamps from 1852 Onwards

LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS POSTAGE STAMPS – PRE-INDEPENDENCE Year Denomination Particulars 1 1852 /2a SCINDE DAWK 1 1854 /2a EAST INDIA CO, ISSUES 1a -do- 4a -do- 1854 4a QUEEN VICTORIA 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 1855 4a -do- 8a -do- 1 1856-64 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- UNDER THE CROWN - QUEEN 1860 8p VICTORIA 1 1865 /2a Elephant’s Head Watermark 8p -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- 1866 6a -do- 1866-67 4a Octagonal design 6a8p -do- 1868 8a Die II 1 1873 /2a -do- 1874 9p -do- 1r -do- 1876 6a 12a 1 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 1 1882-88 /2a Empire of India – Queen Victoria 9p -do- 1a -do- 1a6p -do- 2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 4a6p -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1R -do- 1 1891 2 /2a Surcharged 1 1892-97 2 /2a 1r 1895 2r 3r 5r 1 1898 /4a 1899 3p 1900-02 3p 1 /2a 1a 2a 1 2 /2a 1902-11 3p KING EDWARD VII 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 6a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 2 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 3r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1 1905 /4a Surcharged 1 1906 /2a Postage and Revenue 1a -do- 1911 3p KING GEORGE V 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 1 1 /2a -do- 2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 6a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1921 9p Surcharged 1 1922 /4a -do- 1922-26 1a Colours changed 1 1 /2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 1926-31 3p Printed at ISP Nasik 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 1 1 /2a -do- 2a -do- 3 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1929 2a Air Mail Series 3a -do- 4a