Human Rights in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

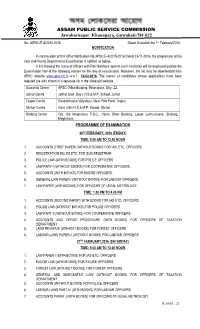

Notification: Half Yearly Departmental Examination-2015

ASSAM PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Jawaharnagar, Khanapara, Guwahati-781 022 No. 30PSC/E-4/2015-2016 Dated Guwahati the 1st February/2016 NOTIFICATION In continuation of this office Notification No.3PSC/E-4/2015-2016 Dated 23-11-2016, the programme of the next Half-Yearly Departmental Examination is notified as below. A list showing the name of officers with Roll Numbers against each candidate will be displayed outside the Examination Hall at the following centres on the day of examination. Moreover, the list may be downloaded from APSC website www.apsc.nic.in w.e.f. 10-02-2016. The names of candidates whose applications have been rejected are also shown in a separate list in the aforesaid website. Guwahati Centre APSC Office Building , Khanapara, Ghy. -22. Jorhat Centre Jorhat Govt. Boy’s H.S & M.P. School, Jorhat Tezpur Centre Rastrab has ha Vidyalaya , Near Polo Field, Tezpur Silchar Centre Govt. Girls H.S & M.P. School, Silchar Shillong Cen tre O/o. the Meghalaya P.S.C., Horse Shoe Building, Lower Lachumiaere, Shillong, Meghalaya. PROGRAMME OF EXAMINATION 26 TH FEBRUARY, 2016 (FRIDAY) TIME: 9.00 AM TO 12.00 NOON 1. ACCOUNTS (FIRST PAPER) WITHOUT BOOKS FOR IAS, ETC. OFFICERS 2. REGISTRATION RULES ETC. FOR SUB-REGISTRAR 3. POLICE LAW (WITH BOOKS) FOR POLICE OFFICERS 4. LAW PART-I (WITHOUT BOOKS) FOR COOPERATIVE OFFICERS. 5. ACCOUNTS (WITH BOOKS) FOR EXCISE OFFICERS. 6. GENERAL LAW PAPER-I (WITHOUT BOOKS) FOR LABOUR OFFICERS 7. LAW PAPER (WITH BOOKS) FOR OFFICERS OF LEGAL METROLOGY. TIME: 1.00 PM TO 4.00 PM 1. -

Hand Book V-II (3).Pdf

You are requested to give effect to such concession as usual, and you are also requested to indicate the caste of the applicant(s) while stibmitting proposals to the Government for Settlement of land or conversion of A. P. lands into periodic Pattas as necessary, so that the concession as stated above may be extended to the persons of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Yours faithfully, Sd/-D. K. GANGOPADHYAY, Commissioner & Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Revenue (S) Department, Dispur. Memo No. RSD. 8/87/47-A Dt. Dispur, the 3rd May, 1990 Copy forwarded to :– (1) The Chairman, Assam Board of Revenue, Guwahati-I. (2) The Commissioner, W. P. T. & B. C. Department, Dispur. (3) The Commissioner of Division & B. C. Department, Dispur. (4) The Director of Land Records, Assam, Bamunimaidan, Ghy-21. (5) The Director of Land Requisition, Acquisition & Reforms, Assam Guwahati-l . (6) The Principal, Assam Survey & Settlement Training Centre, Dakhingaon, Guwahati-28. (7) Guard File. By Order etc., Sd/-D. K. GANGOPADHYAY, Commissioner & Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Revenue (S) Department, Dispur. (121) GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM REVENUE (SETTLEMENT) DEPARTMENT SETTLEMENT BRANCH No. RSD. 8/87/49 Dated Dispur, the 10th May, 1990 From : Shri D. K. Gangopadhyay, IAS, Commissioner & Secretary to the Government of Assam. To The Deputy Commissioner ________________________ The Settlement Officer ________________________ The Sub-Divisional Officer ________________________ (Except Karbi Anglong & N. C. Hills Districts) Sub. : Preservation of PGRs/VGRs and other reservation for public purposes and ecological balance. Sir, You are aware perhaps that the Government have emphasised on preserving the existing PGRs and VGRs in the State for use by the public for the purpose for which the reserves have been constituted and removal of the encroachments on the PGRs and VGRs as per Settlement Rules 18(2) and Section 165 under the Chapter X of the ALRR 1886 (amended) in time and without delay. -

The TAI AHOM Movement in Northeast India: a Study of All Assam TAI AHOM Student Union

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 7, Ver. 10 (July. 2018) PP 45-50 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The TAI AHOM Movement in Northeast India: A Study of All Assam TAI AHOM Student Union Bornali Hati Boruah Research Scholar Dept. of Political science Assam University, Diphu campus, India Corresponding Author: Bornali Hati Boruah Abstract: The Ahoms, one of the foremost ethnic communities in the North East India are a branch of the Tai or Shan people. The Tai Ahoms entered the Brahmaputra valley from the east in the early part of the thirteenth century and their arrival heralded a new age for the people of the region. The ethnic group Tai Ahoms of Assam has been asserting their ethnic identity more than a century old today. The Ahoms who once ruled over Assam seek to maintain their distinct identity within the larger Assamese society. The Tai Ahoms of Assam faced a lot of problem after independence in different aspects. Moreover, though once Tai Ahoms ancestors were ruling race but today they have been squarely backward .They have been recognized as one of the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. As a measure to solve their multifold and multifaceted demands, the ethnic group Tai Ahoms has been struggling through their organizations. In present time, All Tai Ahom Student Union (ATASU) has been very much concerned about the various problems of Tai Ahoms community. While struggling for the overall development of the Tai Ahom community, rightly or wrongly the All Tai Ahom Student Union has been raising political issues and thus got involved in the politics of the state despite being a non-political organization. -

International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI

SJIF Impact Factor: 6.047 Volume: 6 | November - October 2019 -2020 ISSN(Print ): 2250 – 2017 International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI : https://doi.org/10.36713/epra0003 IDENTITY MOVEMENTS AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN ASSAM Ananda Chandra Ghosh Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Cachar College, Silchar,788001,Assam, India ABSTRACT Assam, the most populous state of North East India has been experiencing the problem of internal displacement since independence. The environmental factors like the great earth quake of 1950 displaced many people in the state. Flood and river bank erosion too have caused displacement of many people in Assam every year. But the displacement which has drawn the attention of the social scientists is the internal displacement caused by conflicts and identity movements. The Official Language Movement of 1960 , Language movement of 1972 and the Assam movement(1979-1985) were the main identity movements which generated large scale violence conflicts and internal displacement in post colonial Assam .These identity movements and their consequence internal displacement can not be understood in isolation from the ethno –linguistic composition, colonial policy of administration, complex history of migration and the partition of the state in 1947.Considering these factors in the present study an attempt has been made to analyze the internal displacement caused by Language movements and Assam movement. KEYWORDS: displacement, conflicts, identity movements, linguistic composition DISCUSSION are concentrated in the different corners of the state. Some of The state of Assam is considered as mini India. It is these Tribes have assimilated themselves and have become connected with main land of India with a narrow patch of the part and parcel of Assamese nationality. -

'Bihu' in Assam Movement

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 12, No. 1, January-March, 2020. 1-11 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n1/v12n102.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n1.02 The Political role of ‘Bihu' in Assam movement (1979) Debajit Bora Assistant Professor, Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, Jamia Millia Islamia, [email protected], ORCID id: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6424-2522 Abstract This paper aims to understand the political role of Assamese traditional performance ‘Bihu’ during Assam movement in 1979. It argues that beyond its role as Assamese cultural identity, ‘Bihu’ had transformed itself into a political space and fueled upon expanding the idea of Stage Bihu. While looking at the performance as medium of political messaging, the paper brings together the three specific case studies seemingly unknown in the documented cultural history and located in the rural Assam. The idea is to comprehend the larger scope of traditional performance in accommodating political events. The debates are being weaved together through theoretical frames of historian Eric Hobsbawm’s ‘Inventing tradition’ Thomas Postlewait’s ‘theatre event’ in order to see the transformation and changes within the repertoire of Bihu. The paper tries to resurrect an alternative historical discourse, often neglected by the dominant historical cannons. Keywords: performance, identity, Assam movement, politics, Assam. Introduction Assam movement, 1979 had emerged as one of the strong identity assertion movement in post Independent India mainly revolved around the issue illegal migration from Bangladesh. On June 8, 1979, the All Assam Students Union (AASU) sponsored a 12-hour general strike (bandh) in the state to demand the "detection, disenfranchisement and deportation" of foreigners. -

Training Report for the Month of October 2016

TRAINING REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF OCTOBER 2016 Training activities on Disaster Management (October, 2016 Report) Disaster Management is an area where people with necessary skills and expertise to carry the risk of facilitating disasters rather than prevent, mitigate or respond to them effectively. Therefore “Training” is an important component of the Disaster management system. It facilitates the strengthening of response mechanism as well as empowers all the stakeholders to take appropriate preparedness measures. The Community Based Disaster Preparedness (CBDP) training module is designed so as to prepare the community level volunteers/ organizations to deal with an emergency situation that may arise due to different hazards. The course provides the opportunity to learn essential knowledge and skills in disaster and to address implementation challenges in a systematic manner. The participants are provided with practical tools for design and implementation of programs for disaster preparedness through community capacity to promote a culture of safety. The NGO volunteers, CBO, Mahila Samittees, Gram Sevak, Self Help Groups, Anganwadi, ASHA etc. are targeted to be trained in CBDP. The Training on Public Health in Emergencies (PHE) is aimed at giving specialised guidance in public health promotion and protection, disease prevention, health assessment and disease surveillance during an emergency. State, local and block level Public Health Engineering officials; Health; and Social Welfare Department officials working in various sectors of sanitation & hygiene promotion are usually targeted as they are the immediate responders to these situations and they should have immediate access to guidance and information that will assist them in rapidly establishing priorities of undertaking necessary actions during the response to an emergency or disaster besides being duly prepared if any such calamity strikes. -

Actual and Ideal Fertility Differential Among Natives, Immigrants, and Descendants of Immigrants in a Northeastern State of India

Accepted: 24 January 2019 DOI: 10.1002/psp.2238 RESEARCH ARTICLE Actual and ideal fertility differential among natives, immigrants, and descendants of immigrants in a northeastern state of India Nandita Saikia1,2 | Moradhvaj2 | Apala Saha2,3 | Utpal Chutia4 1 World Population Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Abstract Laxenburg, Austria Little research has been conducted on the native‐immigrant fertility differential in 2 Centre for the Study of Regional low‐income settings. The objective of our paper is to examine the actual and ideal fer- Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, India tility differential of native and immigrant families in Assam. We used the data from a 3 Department of Geography, Institute of primary quantitative survey carried out in 52 villages in five districts of Assam during Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 2014–2015. We performed bivariate analysis and used a multilevel mixed‐effects lin- India 4 Department of Anthropology, Delhi ear regression model to analyse the actual and ideal fertility differential by type of vil- University, Delhi, India lage. The average number of children ever‐born is the lowest in native villages in Correspondence contrast to the highest average number of children ever‐born in immigrant villages. Dr. Nandita Saikia, Post Doc Scholar, The likelihood of having more children is also the highest among women in immigrant International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Schlossplatz 1, 2361 Laxenburg, villages. However, the effect of religion surpasses the effect of the type of village the Austria. women reside in. Email: [email protected] Funding information KEYWORDS Indian Council of Social Science Research, Assam, fertility, immigrants, India, native, religion Grant/Award Number: RESPRO/58/2013‐14/ ICSSR/RPS 1 | INTRODUCTION fertility of immigrants and their descendants can be an important indi- cator of social integration over time (Dubuc, 2012). -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused. -

No. 136 PSC/CON/E-140/HYDE/2014-15 Dated Guwahati the 12Th November, 2015 NOTIFICATION in Exercise of the Powers Conferred on T

No. 136 PSC/CON/E-140/HYDE/2014-15 Dated Guwahati the 12 th November, 2015 NOTIFICATION In exercise of the powers conferred on the Assam Public Service Commission vide Government Notification No. AAP/180/69/4 Dtd. 27-08-69, the Commission is pleased to declare the results of the Half-Yearly Departmental Examination for Tribal Language held on 12/07/2015 at Guwahati in respect of Officers who have responded to this Office Notification No. 1PSC/E-5/2014- 2015 Dtd. Guwahati the 27 th November, 2014. The following Officers are declared to have passed in the Tribal Language which are shown against their names. Language Sl. Name and Designation Roll No. in which No. passed PALASH PRATIM BORA, ACS, CIRCLE OFFICER, AGAMONI REVENUE 1. 24 BODO CIRCLE, DHUBRI DEB ASIS BORAH,ACS, EAC & EXECUTIVE MAGISTRATE ,DIPHU, KARBI 2. 30 BODO ANGLONG 3. VICTORY KHAKHOLIA, SUPDT. OF TAXES, BARPETA UNIT, ASSAM 101 BODO 4. JINTU MONI LAHKAR, SUPDT. OF TAXES, GOALPARA 102 BODO MD. AYAT ULLAH, SUPDT. OF TAXES, BISWANATH CHARIALI, 5. 105 BODO SONITPUR, 6. NIREN BHATTACHARJYA, INSP.OF TAXES, MANGALDAI, DARRANG 117 BODO 7. TRIDISHA DUARAH, INSP. OF TAXES, NAGAON ZONE, NAGAON 119 BODO 8. NASHRIN JEBIN, INSP.OF TAXES, NAGAON ZONE, NAGAON, 120 BODO 9. PUBALI BARUAH, O/O SUPDT. OF TAX, NALBARI 121 BODO FARUKH AHMED, INSP.OF TAXES, O/O-THE SUPDT. OF TAXES, 10. 132 BODO NALBARI, 11. PANKAJ SONOWAL, INSP.OF TAXES, GHY. 142 BODO 12. IMDAD ALI, INSP. OF TAXES, TANGLA, UDALGURI, 156 BODO 158 13. KARUNA KANTA SAIKIA, INSP. -

Socio-Cultural History of Assam: a B Rief Reflection

SOCIO-CULTURAL HISTORY OF ASSAM: A BRIEF REFLECTION DR. NURUL ISLAM CHAKDAR, Assistant Professor of History Abhayapuri College, Abhayapuri, Bongaigaon, Assam Abstract It would not be an exaggeration if we claim that the land of Assam is multicultural. It reflects that its socio-cultural history is diversity. However, nobody can deny unity among diversity in Assamese culture is composite. Even the society of Assam is a heterogeneous society. It has a unique variety of peoples of different human races. Sociological plurality is the main concept of Assamese society. In a sense, Assamese society is the outcome of different elements (castes and sub-castes), for example, between the pre-Aryan races and tribes and the Aryans etc. Different castes and sub-castes and so on makes dynamic social pattern of Assam. The present paper is an attempt to show how many ways the assimilation of various religious groups, castes and sub- castes makes composite culture or the social culture of Assam is the product of historical development. Briefly speaking, the different castes and sub-castes or classes ostensively have made the Assamese society as a plural society before the world. Key words: Assimilation, culture, heterogeneous, historical, society. Assam has a unique variety of peoples of different human race and of culture of both hills and plains. It comprises of different races and tribes or different socio-economic groups. The Assamese society, therefore, is a heterogeneous society. The Assamese society is a multi cultural, multi ethnic, multi religious and multi lingual society. Thus, sociological plurality is the key concept of Assamese society. -

Conflict Mapping and Peace Processes in North East India Conflict Mapping and Peace Processes in Northeast India

Conflict Mapping And Peace Processes in North East India Conflict Mapping and Peace Processes in Northeast India © North Eastern Social Research Centre 2008 Published by: North Eastern Social Research Centre 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Guwahati 781004 Assam, India Edited by : Tel. (0361) 2602819 Fax: (91-361) 2732629 (Attn NESRC) Lazar Jeyaseelan Email: [email protected] Website : www.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/NESRC Cover page designed by: Kazimuddin Ahmed Panos South Asia 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Guwahati 781001 Assam, India Printed at : Saraighat Laser Print North Eastern Social Research Centre Guwahati III IV Dedication Acknowledgement Dr. Lazar Jeyaseelan who had accepted the responsibility of edit- ing this book phoned and told me on 12th April 2007 that he had done what he could, that he was sending the CD to me and that This volume comes out of the efforts of some civil society organisations that wanted to go beyond relief and charity to explore I should complete this work. He must have had a premonition avenues of peace. Realising that a better understanding of the issues because he died of a massive heart attack two days later during involved in conflicts and peace building was required, they encouraged a public function at Makhan Khallen village, Senipati District, some students and other young persons to do a study of a few areas Manipur. of tension. The peace fellowships were advertised and the applicants were interviewed. Those appointed for the task were guided by Dr Jerry Born at Madhurokkanmoi in Tamil Nadu on 24th June Thomas, Dr L. Jeyaseelan and Dr Walter Fernandes. -

Half Yearly Departmental Examination for Tribal Language

ASSAM PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Jawaharnagar, Khanapara, Guwahati-781 022 No. 174PSC/CON/E-94/HYDE/2013-2014 Dated Guwahati the 21 st November, 2014 NOTIFICATION In exercise of the powers conferred on the Assam Public Service Commission vide Government Notification No. AAP/180/69/4 Dtd. 27-08-69, the Commission is pleased to declare the results of the Half-Yearly Departmental Examination for Tribal Language held on 09/01/2014 at Guwahati in respect of Officers who have responded to this Office Notification No. 1PSC/E-6/2013- 2014 Dtd. Guwahati the 12 th September, 2013. The following Officers are declared to have passed in the Tribal Language which are shown against their names. Language Sl. Name and Designation Roll No. in which No. passed 1. SRI PALLAV JYOTI NATH, ACS, EAC, BONGAIGAON. 9 MISHING 2. SRI KARTIK KALITA, ACS, EAC, NALBARI, DC OFFICE, NALBARI. 10 MISHING 3. SMTI SANTANA BORA, ACS, EAC, BARPETA, 14 MISHING SMTI MADHUMITA NATH, ACS, CIRCLE OFFICER, BAGRIBARI REVENUE 4. 17 MISHING CIRCLE, BILASIPARA SUB-DIV.(CIVIL), DHUBRI. 5. SMTI. PREETY LEKHA DEKA, ACS, EAC, GOALPARA. 18 MISHING 6. SHRI MOHORSII KASHYAP, ACS,EAC, GOALPARA, 19 MISHING 7. SRI GARGA MOHAN DAS, ACS, EAC, KOKRAJHAR. 25 MISHING 8. SRI ROKTIM BORUAH, ACS, EAC, DC OFFICE NALBARI. 28 MISHING 9. CHAYANIKA THAKURIA, ACS, EAC & EM, DHUBRI 30 MISHING 10. SRI KAMAL BARUAH,ACS, EAC & EM, DHUBRI 31 MISHING 11. DYOTIVA BORA, ACS, EAC & EM , DHUBRI, 32 MISHING SRI SHYAMAL KSHETRA GOGOI,ACS, ELECTION OFFICER, SADIYA, 12. 33 MISHING TINSUKIA 13. SMT. DEBAHUTI BORA, ACS, EAC,DIPHU, KARBI ANGLONG 37 MISHING [2] Language Sl.