Rarity in Astragalus: a California Perspective Philip W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Leguminosae): Nomenclatural Proposals and New Taxa

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 58 Number 1 Article 5 1-30-1998 Astragalus (Leguminosae): nomenclatural proposals and new taxa Stanley L. Welsh Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Welsh, Stanley L. (1998) "Astragalus (Leguminosae): nomenclatural proposals and new taxa," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 58 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol58/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 58(1), © 1998, pp. 45-53 ASTRAGALUS (LEGUMINOSAE): NOMENCLATURAL PROPOSALS AND NEW TAXA Stanley L. Welsh! ABSTRACT.-As part of an ongoing summary revision of Astragalus for the Flora North America project, several nomenclatural changes are indicated. Nomenclatural proposals include A. molybdenus val'. shultziorom (Barneby) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. australis var. aboriginorom (Richardson) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. australis var. cattoni (M.E. Jones) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. aU8tralis var. lepagei (Hulten) Welsh, comb. nov; A. australis var. muriei (Hulten) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. subcinereus var. sileranus (M.E. Jones) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. tegetariaides val'. anxius (Meinke & Kaye) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. ampullarioides (Welsh) Welsh, comb. nov.; A. cutlen (Barneby) Welsh, comb. nov.; and A. laccaliticus (M.E. Jones) Welsh, comb. nov. Proposals of new taxa include Astragalus sect. Scytocarpi subsect. Micl'ocymbi Welsh, subsed. nov., and A. sabulosus var. -

Appendix F3 Rare Plant Survey Report

Appendix F3 Rare Plant Survey Report Draft CADIZ VALLEY WATER CONSERVATION, RECOVERY, AND STORAGE PROJECT Rare Plant Survey Report Prepared for May 2011 Santa Margarita Water District Draft CADIZ VALLEY WATER CONSERVATION, RECOVERY, AND STORAGE PROJECT Rare Plant Survey Report Prepared for May 2011 Santa Margarita Water District 626 Wilshire Boulevard Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90017 213.599.4300 www.esassoc.com Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego San Francisco Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills D210324 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cadiz Valley Water Conservation, Recovery, and Storage Project: Rare Plant Survey Report Page Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................2 Objective .......................................................................................................................... 2 Project Location and Description .....................................................................................2 Setting ................................................................................................................................... 5 Climate ............................................................................................................................. 5 Topography and Soils ......................................................................................................5 -

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

Genetic Characterization of Three Varieties of Astragalus Lentiginosus (Fabaceae)

Genetic characterization of three varieties of Astragalus lentiginosus (Fabaceae) BRIANJ. KNAus,' RICHC. CRONN,AND AARONLISTON I Knaus, B. J. (Oregon State University, Department of Botany and Plant Pa- thology, 2082 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, OR, 97331-2902, U.S.A.; e-mail: [email protected]), R. C. Cronn (USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, OR, 97331, U.S .A.; e-mail: [email protected]) & A. Liston (Oregon State University, Depart- ment of Botany and Plant Pathology, 2082 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, OR, 97331- 2902, U.S.A.; e-mail: [email protected]).Genetic characterization of three varieties of Astragalus lentiginosus (Fabaceae). Brittonia 57: 334-344. 2005.-Astragalus lentiginosus is a polymorphic species that occurs in geologi- cally young habitats and whose varietal circumscription implies active morpho- logical and genetic differentiation. In this preliminary study, we evaluate the po- tential of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers to resolve infraspecific taxa in three varieties of Astragalus lentiginosus. Distance-based principle coordinate and neighbor-joining analyses result in clustering of individ- uals that is congruent with population origin and varietal circumscription. Anal- ysis of molecular variance of two Oregon varieties demonstrates that varietal categories account for 11% of the total variance; in contrast, geographic proximity does not contribute to the total variance. AFLPs demonstrate an ability to dis- criminate varieties of A. lentiginosus despite a potentially confounding geographic pattern, and may prove effective at inferring relationships throughout the group. Key words: AFLP, amplified fragment length polymorphism, Astragalus lenti- ginosus, genetic differentiation, infraspecific taxa. Astragalus lentiginosus Dougl. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

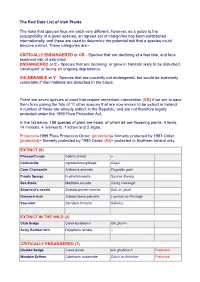

The Red Data List of Irish Plants

The Red Data List of Irish Plants The risks that species face are each very different, however, as a guide to the susceptibility of a given species, an agreed set of categories has been established internationally, and these are used to determine the potential risk that a species could become extinct. These categories are:- CRITICALLY ENDANGERED or CR - Species that are declining at a fast rate, and face imminent risk of extinction. ENDANGERED or E - Species that are declining, or grow in habitats likely to be disturbed, 'developed' or facing an ongoing degradation. VULNERABLE or V - Species that are currently not endangered, but would be extremely vulnerable if their habitats are disturbed in the future. There are seven species of plant that require immediate intervention (CR) if we are to save them from joining the fate of 11 other species that are now known to be extinct in Ireland. A number of these are already extinct in the Republic, and are not therefore legally protected under the 1999 Flora Protection Act. In the list below, 188 species of plant are listed, of which 64 are flowering plants, 4 ferns, 14 mosses, 4 liverworts, 1 lichen and 2 algae. Protected=1999 Flora Protection Order; (protected)= formerly protected by 1987 Order; {protected}= formerly protected by 1980 Order; (NI)= protected in Northern Ireland only. EXTINCT (9) Pheasant's-eye Adonis annua -- Corncockle Agrostemma githago Cogal Corn Chamomile Anthemis arvensis Fíogadán goirt Purple Spurge Euphorbia peplis Spuirse dhearg Sea Stock Matthiola sinuata Tonóg chladaigh -

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice

Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center University of California, Irvine UCI – NATURE and UC Natural Reserve System California State Parks – Colorado Desert District Anza-Borrego Desert State Park & Anza-Borrego Foundation Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice (revised 1/31/2019) A gaggle of geneticists in Borrego Palm Canyon – 1975. (L-R, Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky, Dr. Steve Bryant, Dr. Richard Lewontin, Dr. Steve Jones, Dr. TimEDITOR’S Prout. Photo NOTE by Dr. John Moore, courtesy of Steve Jones) Editor’s Note The publications cited in this volume specifically mention and/or discuss Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, locations and/or features known to occur within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, biological, geological, paleontological or anthropological specimens collected from localities within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, or events that have occurred within those same boundaries. This compendium is not now, nor will it ever be complete (barring, of course, the end of the Earth or the Park). Many, many people have helped to corral the references contained herein (see below). Any errors of omission and comission are the fault of the editor – who would be grateful to have such errors and omissions pointed out! [[email protected]] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As mentioned above, many many people have contributed to building this database of knowledge about Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. A quantum leap was taken somewhere in 2016-17 when Kevin Browne introduced me to Google Scholar – and we were off to the races. Elaine Tulving deserves a special mention for her assistance in dealing with formatting issues, keeping printers working, filing hard copies, ignoring occasional foul language – occasionally falling prey to it herself, and occasionally livening things up with an exclamation of “oh come on now, you just made that word up!” Bob Theriault assisted in many ways and now has a lifetime job, if he wants it, entering these references into Zotero. -

New Combination in Astragalus (Fabaceae)

Smith, J.F. and J.C. Zimmers. 2017. New combination in Astragalus (Fabaceae). Phytoneuron 2017-38: 1–3. Published 1 June 2017. ISSN 2153 733X NEW COMBINATION IN ASTRAGALUS (FABACEAE) JAMES F. SMITH and JAY C. ZIMMERS Department of Biological Sciences Snake River Plains Herbarium Boise State University Boise, Idaho 83725 [email protected] ABSTRACT Recent molecular phylogenetic analyses have established that the four varieties of Astragalus cusickii are three distinct, monophyletic clades: A. cusickii var. cusickii and A. cusickii var. flexilipes form one clade, A. cusickii var. sterilis and A. cusickii var. packardiae each form the other two. Although relationships among the clades in the analyses are poorly resolved, they are also poorly resolved with respect to other recognized species in the genus. Morphological data provide unique synapomorphies for each of the clades and therefore we propose to recognize three distinct species, with A. cusickii var. flexilipes retained at the rank of variety. A new combination brings A. cusickii var. packardiae to species rank, as Astragalus packardiae (Barneby) J.F. Sm. & Zimmers, comb. nov. , whereas A. sterilis has already been published. Astragalus L. is a diverse group of approximately 2500 species (Frodin 2004; Lock & Schrire 2005; Mabberley 2008) and has a rich diversity in four geographic areas (southwest and south-central Asia, the Sino-Himalayan region, the Mediterranean Basin, and western North America; in addition the Andes in South America have at least 100 species. Second to Eurasia in terms of species diversity is the New World, with approximately 400-450 species. The Intermountain Region of western North America (Barneby 1989) is especially diverse, and an estimated 70 species of Astragalus can be found in Idaho alone, including several endemic taxa (Mancuso 1999). -

Designation of Critical Habitat for Five Carbonate Plants from the San Bernardino Mountains in Southern California; Final Rule

Tuesday, December 24, 2002 Part II Department of the Interior 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Five Carbonate Plants From the San Bernardino Mountains in Southern California; Final Rule VerDate 0ct<31>2002 21:23 Dec 23, 2002 Jkt 200001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\24DER2.SGM 24DER2 78570 Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 247 / Tuesday, December 24, 2002 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: The and a number of private stakeholders Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office, at the (e.g., mining interests) are in the process Fish and Wildlife Service above address; telephone 760/431–9440, of developing the Carbonate Habitat facsimile 760/431–5902. Information Management Strategy (draft CHMS) to 50 CFR Part 17 regarding this designation is available in conserve four of the five subject alternate formats upon request. carbonate plants while accommodating RIN 1018–AI27 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: other land uses. The USFS is the lead agency for this action. The goals of the Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Background and Plants; Designation of Critical CHMS are: (1) To protect the listed Habitat for Five Carbonate Plants From The five plants addressed in this plants and the habitat components they the San Bernardino Mountains in designation of critical habitat, require; (2) to guide impact Southern California Astragalus albens (Cushenbury milk- minimization and compensation for vetch), Erigeron parishii (Parish’s daisy), unavoidable impacts; (3) to streamline AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Eriogonum ovalifolium var. vineum reviews of mining activities in carbonate Interior. -

Special Status Species Potentially Occurring on Site Special-Status Plant Species Evaluated for Potential to Occur on the Loyola Marymount University Campus

Special Status Species Potentially Occurring On Site Special-Status Plant Species Evaluated for Potential to Occur on the Loyola Marymount University Campus Scientific Name Status Potential for Occurrence Common Name Federal State CNPS Habitat Requirements and Survey Results Aphanisma blitoides -- -- 1B.2 Coastal bluff scrub, None: Suitable habitat is not Aphanisma coastal dunes, coastal present because of the scrub. Occurs on bluffs developed nature of the and slopes near the Proposed Project site. ocean in sandy or clay soils. In steep decline on the islands and the mainland. Arenaria paludicola -- -- 1B.1 Occurs in marshes and None: Suitable habitat is not Marsh sandwort swamps. present on the Proposed Growing up through Project site. dense mats of typha, juncus, scirpus, etc., in freshwater marsh. Astragalus brauntonii FE 1B.1 Found in closed-cone None: Suitable habitat is not Braunton's milk-vetch coniferous forest, present because of the chaparral, coastal scrub, developed nature of the valley and foothill project site. grassland; Recent burns or disturbed areas; in stiff gravelly clay soils overlying granite or limestone. Astragalus FE CE 1B.1 Foundincoastalsalt None: Suitable habitat is not pycnostachyus var. marsh. Within reach of present on the Proposed lanosissimus high tide or protected Project site. Ventura Marsh milk- by barrier beaches, vetch more rarely near seeps on sandy bluffs. Astragalus tener var. titi FE CE 1B.1 Foundincoastalbluff None: Suitable habitat is not Coastal dunes milk- scrub, coastal dunes; present on the Proposed vetch moist, sandy Project site. depressions of bluffs or dunes along and near the pacific ocean; one site on a clay terrace. -

Lowland Calcareous Grassland (Uk Bap Priority Habitat)

LOWLAND CALCAREOUS GRASSLAND (UK BAP PRIORITY HABITAT) Summary These are unimproved grasslands on base-rich soils in the southern and eastern Scottish lowlands. They consist of mixtures of grasses growing with a rich array of herbs including small base-tolerant herbs. These grasslands typically occur as small patches among mosaics with acid and neutral grasslands (including agriculturally improved grasslands), scrub and rock outcrops, and are most common on southerly aspects. Their total extent in Scotland was estimated in 2004 to be only 46 hectares. They are of high conservation value in being small patches of very concentrated high diversity within larger landscapes dominated by intensively managed farmland. They are home to some uncommon plant species and are an important food source for grazing mammals, invertebrates and birds. They are produced and maintained by grazing, which is needed to keep larger, more vigorous plants in check and thereby maintain high botanical diversity. What is it? Lowland calcareous grasslands are communities of thin, dry, base-rich mineral soils derived from rocks such as limestone, various igneous rocks and some sandstones. They are notable for being generally rich in species, including several small, low-grown herbs. Low shoots or mats of wild thyme Thymus polytrichus are invariably present and serve to distinguish the vegetation from neutral and acid grasslands. Some stands also contain similar low mats of common rockrose Helianthemum nummularium. The main sward is short and made up mainly of the grasses sheep’s fescue Festuca ovina, red fescue F. rubra, crested hair-grass Koeleria cristata, meadow oat-grass Helictotrichon pratense, quaking grass Briza media, spring sedge Carex caryophyllea and glaucous sedge C. -

Perennial Grain Legume Domestication Phase I: Criteria for Candidate Species Selection

sustainability Review Perennial Grain Legume Domestication Phase I: Criteria for Candidate Species Selection Brandon Schlautman 1,2,* ID , Spencer Barriball 1, Claudia Ciotir 2,3, Sterling Herron 2,3 and Allison J. Miller 2,3 1 The Land Institute, 2440 E. Water Well Rd., Salina, KS 67401, USA; [email protected] 2 Saint Louis University Department of Biology, 1008 Spring Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (A.J.M.) 3 Missouri Botanical Garden, 4500 Shaw Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63110, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-785-823-5376 Received: 12 February 2018; Accepted: 4 March 2018; Published: 7 March 2018 Abstract: Annual cereal and legume grain production is dependent on inorganic nitrogen (N) and other fertilizers inputs to resupply nutrients lost as harvested grain, via soil erosion/runoff, and by other natural or anthropogenic causes. Temperate-adapted perennial grain legumes, though currently non-existent, might be uniquely situated as crop plants able to provide relief from reliance on synthetic nitrogen while supplying stable yields of highly nutritious seeds in low-input agricultural ecosystems. As such, perennial grain legume breeding and domestication programs are being initiated at The Land Institute (Salina, KS, USA) and elsewhere. This review aims to facilitate the development of those programs by providing criteria for evaluating potential species and in choosing candidates most likely to be domesticated and adopted as herbaceous, perennial, temperate-adapted grain legumes. We outline specific morphological and ecophysiological traits that may influence each candidate’s agronomic potential, the quality of its seeds and the ecosystem services it can provide.