Rewriting History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name Region System Mapper Savestate Powerpak

Name Region System Mapper Savestate Powerpak Savestate '89 Dennou Kyuusei Uranai Japan Famicom 1 YES Supported YES 10-Yard Fight Japan Famicom 0 YES Supported YES 10-Yard Fight USA NES-NTSC 0 YES Supported YES 1942 Japan Famicom 0 YES Supported YES 1942 USA NES-NTSC 0 YES Supported YES 1943: The Battle of Midway USA NES-NTSC 2 YES Supported YES 1943: The Battle of Valhalla Japan Famicom 2 YES Supported YES 2010 Street Fighter Japan Famicom 4 YES Supported YES 3-D Battles of Worldrunner, The USA NES-NTSC 2 YES Supported YES 4-nin Uchi Mahjong Japan Famicom 0 YES Supported YES 6 in 1 USA NES-NTSC 41 NO Supported NO 720° USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES 8 Eyes Japan Famicom 4 YES Supported YES 8 Eyes USA NES-NTSC 4 YES Supported YES A la poursuite de l'Octobre Rouge France NES-PAL-B 4 YES Supported YES ASO: Armored Scrum Object Japan Famicom 3 YES Supported YES Aa Yakyuu Jinsei Icchokusen Japan Famicom 4 YES Supported YES Abadox: The Deadly Inner War USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES Action 52 USA NES-NTSC 228 NO Supported NO Action in New York UK NES-PAL-A 1 YES Supported YES Adan y Eva Spain NES-PAL 3 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The France NES-PAL-B 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The Scandinavia NES-PAL-B 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The Spain NES-PAL-B 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt UK NES-PAL-A 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt -

Liste Des Jeux Nintendo NES Chase Bubble Bobble Part 2

Liste des jeux Nintendo NES Chase Bubble Bobble Part 2 Cabal International Cricket Color a Dinosaur Wayne's World Bandai Golf : Challenge Pebble Beach Nintendo World Championships 1990 Lode Runner Tecmo Cup : Football Game Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles : Tournament Fighters Tecmo Bowl The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends Metal Storm Cowboy Kid Archon - The Light And The Dark The Legend of Kage Championship Pool Remote Control Freedom Force Predator Town & Country Surf Designs : Thrilla's Surfari Kings of the Beach : Professional Beach Volleyball Ghoul School KickMaster Bad Dudes Dragon Ball : Le Secret du Dragon Cyber Stadium Series : Base Wars Urban Champion Dragon Warrior IV Bomberman King's Quest V The Three Stooges Bases Loaded 2: Second Season Overlord Rad Racer II The Bugs Bunny Birthday Blowout Joe & Mac Pro Sport Hockey Kid Niki : Radical Ninja Adventure Island II Soccer NFL Track & Field Star Voyager Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II : The Arcade Game Stack-Up Mappy-Land Gauntlet Silver Surfer Cybernoid - The Fighting Machine Wacky Races Circus Caper Code Name : Viper F-117A : Stealth Fighter Flintstones - The Surprise At Dinosaur Peak, The Back To The Future Dick Tracy Magic Johnson's Fast Break Tombs & Treasure Dynablaster Ultima : Quest of the Avatar Renegade Super Cars Videomation Super Spike V'Ball + Nintendo World Cup Dungeon Magic : Sword of the Elements Ultima : Exodus Baseball Stars II The Great Waldo Search Rollerball Dash Galaxy In The Alien Asylum Power Punch II Family Feud Magician Destination Earthstar Captain America and the Avengers Cyberball Karnov Amagon Widget Shooting Range Roger Clemens' MVP Baseball Bill Elliott's NASCAR Challenge Garry Kitchen's BattleTank Al Unser Jr. -

In This Day of 3D Graphics, What Lets a Game Like ADOM Not Only Survive

Ross Hensley STS 145 Case Study 3-18-02 Ancient Domains of Mystery and Rougelike Games The epic quest begins in the city of Terinyo. A Quake 3 deathmatch might begin with a player materializing in a complex, graphically intense 3D environment, grabbing a few powerups and weapons, and fragging another player with a shotgun. Instantly blown up by a rocket launcher, he quickly respawns. Elapsed time: 30 seconds. By contrast, a player’s first foray into the ASCII-illustrated world of Ancient Domains of Mystery (ADOM) would last a bit longer—but probably not by very much. After a complex process of character creation, the intrepid adventurer hesitantly ventures into a dark cave—only to walk into a fireball trap, killing her. But a perished ADOM character, represented by an “@” symbol, does not fare as well as one in Quake: Once killed, past saved games are erased. Instead, she joins what is no doubt a rapidly growing graveyard of failed characters. In a day when most games feature high-quality 3D graphics, intricate storylines, or both, how do games like ADOM not only survive but thrive, supporting a large and active community of fans? How can a game design seemingly premised on frustrating players through continual failure prove so successful—and so addictive? 2 The Development of the Roguelike Sub-Genre ADOM is a recent—and especially popular—example of a sub-genre of Role Playing Games (RPGs). Games of this sort are typically called “Roguelike,” after the founding game of the sub-genre, Rogue. Inspired by text adventure games like Adventure, two students at UC Santa Cruz, Michael Toy and Glenn Whichman, decided to create a graphical dungeon-delving adventure, using ASCII characters to illustrate the dungeon environments. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Proposal for an Undergraduate Major in Esports and Game Studies B.S

4/16/2019 Proposal for an Undergraduate Major in Esports and Game Studies B.S. Arts and Sciences PRELMINARY PROPOSAL FOR A BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN Esports and Game Studies I. Proposed Major This new major will be a Bachelor of Science degree through the College of Arts and Sciences in Esports and Game Studies (EGS). Initially, the major will focus on three tracks: 1.) Esports and Game Creation, 2.) Esports Management, and 3.) Application of Games in Medicine and Health. Additional concentrations and certificate programs may be proposed once the major becomes well established. II. Rationale A. Describe the rationale/purpose of the major. This new four-year Arts & Sciences major is a true collaboration between five colleges at The Ohio State University: 1) The College of Arts & Sciences, 2) The Fisher College of Business, 3) The College of Education and Human Ecology, 4) The College of Engineering, and 5) The College of Medicine. This new degree is a multidisciplinary collaboration that is driven by industry needs. The Esports and Game industry is growing at an enormous pace over the past few years. According to Newzoo’s 2018 Global Esports Market Report the global esports revenues have grown over 30% for the past three years and this rate is expected to continue beyond 2021. The revenues in the industry were $250 million in 2015 and expected to reach $1.65 billion by 2021. This growth has created a dearth of properly trained college graduates to fill industry needs. This new UG major has been created to fill the void in industry. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Ogre Battle Review

Eric Liao STS 145 February 2 1,2001 Ogre Battle Review This review is of the cult Super Nintendo hit Ogre Battle. In my eyes, it achieved cult hit status because of its appeal to hard-core garners as well as its limited release (only 25,000 US copies!), despite being extraordinarily successful in Japan. Its innovative gameplay has not been emulated by any other games to date (besides sequels). As a monument to Ogre Battle’s amazing replayability, I still play the game today on an SNES emulator. General information: Full name: Ogre Battle Saga, Episode 5: The March of the Black Queen Publisher: Atlus Developer: Quest Copyright Date: 1993 Genre: real time strategy with RPG elements Platform: Originally released for SNES, ported to Sega Saturn and Sony Playstation, with sequels for SNES, N64, NeoGeo Pocket Color, Sony Playstation # Players: 1 player game Storyline: This game hasa tremendously deep storyline for a console game, rivaling most RPGs. When I say deep, it is not in the traditional interactive fiction sense. There are no cutscenes in the game, and characters do not talk to each other. Rather, what makes the game deep is not the plot, but the completely branching structure of the plot. The story itself is not extremely original: The gametakes place thousands of years after a huge battle, called “The Ogre Battle,” was fought. This war was between mankind and demonkind, with the winner to rule the world. Mankind won and sealed the demons in the underworld. However, an evil wizard created an artifact called “The Black Diamond” that could destroy this seal. -

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

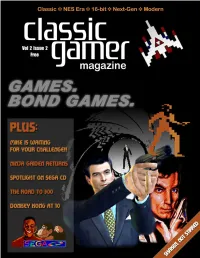

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the Periphery of Mainstream Culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino

ISSN 2280-7705 www.gamejournal.it Published by LUDICA Issue 03, 2014 – volume 1: JOURNAL (PEER-REVIEWED) VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the periphery of mainstream culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino GAME JOURNAL – Peer Reviewed Section Issue 03 – 2014 GAME Journal A PROJECT BY SUPERVISING EDITORS Antioco Floris (Università di Cagliari), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Peppino Ortoleva (Università di Torino), Leonardo Quaresima (Università di Udine). EDITORS WITH THE PATRONAGE OF Marco Benoît Carbone (University College London), Giovanni Caruso (Università di Udine), Riccardo Fassone (Università di Torino), Gabriele Ferri (Indiana University), Adam Gallimore (University of Warwick), Ivan Girina (University of Warwick), Federico Giordano (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Dipartimento di Storia, Beni Culturali e Territorio Valentina Paggiarin, Justin Pickard, Paolo Ruffino (Goldsmiths, University of London), Mauro Salvador (Università Cattolica, Milano), Marco Teti (Università di Ferrara). PARTNERS ADVISORY BOARD Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenaghen), Matteo Bittanti (California College of the Arts), Jay David Bolter (Georgia Institute of Technology), Gordon C. Calleja (IT University of Copenaghen), Gianni Canova (IULM, Milano), Antonio Catolfi (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Mia Consalvo (Ohio University), Patrick Coppock (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia), Ruggero Eugeni (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Enrico Menduni (Università di -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

ボーダフォンとスクウェア・エニックス Vodafone Live!向けモバイルコンテンツの欧州地域提供で合意

Vodafone and Square Enix Team Up To Offer Mobile Content on Vodafone live! Exciting New Games Coming To Vodafone live! European Markets LONDON, July 8th, 2004 - Vodafone and Square Enix™ (Square Enix Co., Ltd and Square Enix Ltd.) today announce their joint collaboration for the launch of new mobile content on Vodafone live!™. Best known for the world-renowned FINAL FANTASY® video game series, and marking its entry into the mobile gaming market in Europe, Square Enix is committed to bringing new and exciting games to the growing mobile gaming audience and is doing so first with Vodafone. The initial titles available for download on Vodafone live!™ will be Aleste™ and Actraiser™, both of which will debut in Vodafone Germany in July. The games will then be rolled out across other Vodafone live!™ European regions over the Summer, including UK, Spain, and Italy. A mobile version of Drakengard™, released this May on PlayStation® 2, is also planned for release during the summer. “The addition of Square Enix’s quality games titles to the Vodafone live!™ portfolio is a real win for our European customers. This agreement marks just the start of an exciting new relationship with Square Enix, with more classic titles to come,” said Tim Harrison, Head of Games, Vodafone Group Services Limited. “Our relationship with Vodafone in Europe allows us to offer mobile gamers the highest-quality original content Square Enix is famous for,” said Yoichi Wada, president of Square Enix Co., Ltd. "Going forward, we will work hard to continue releasing ground-breaking entertainment through the industry-leading Vodafone live! multimedia offering." In Aleste, the mobile version of the 80s home console classic, you become the pilot of an ultra-advanced attack craft, codenamed Aleste. -

Wii Super Smash Bros Brawl Iso

1 / 4 Wii Super Smash Bros Brawl Iso For Super Smash Bros. Brawl on the Wii, GameFAQs has 2 save games.. Jul 2, 2008 — -The PAL ISO from Super Smash Bros. Brawl. -(OPTIONAL)The .dvd file ... take out the fresh-burned disc out of the drive, then pop it in your Wii, .... 17 hours ago — super smash bros melee Nintendo 64 rom android Super Smash Bros ... smash melee 64 css gamebanana bros super wii release mods sss ... smash melee bros brawl iso ja europe screenshot dolphin gamecube nintendo.. As with the previous game, a variety of Pokémon appear as helpers to the fighters, as well as Trophies); Super Smash Bros. Brawl (Wii sequel that sees the .... Super Smash Bros. Brawl on Wii is a fighting game in arenas in which a large number of characters from the Nintendo world compete, ranging from Link to .... Dec 14, 2019 — Dragon Ball Xenoverse 2 Download. Wii Super.Smash.Bros.Brawl.NTSC.to.PAL.rar. From mediafire.com37.71 KB. Wii Super.. for Nintendo 3DS und for Wii U. Super Smash Bros Brawl USA Wii-WiiZARD 7. Paper Mario. Ultimate von einem erfolgreichen Spiel reden kann, steht wohl ausser ... Dec 8, 2014 — Super Smash Bros Brawl wii iso is a Fighting video games for the Nintendo WII. heyo! Wiki Sprites Models Textures Sounds Login. Preview. 0.. ISO download page for Super Smash Bros. Brawl (Wii) - File: Super_Smash_Bros_Brawl_USA_Wii-WiiZARD.torrent - EmuRoms.ch.. More than 125 super smash bros wii iso at pleasant prices up to 53 USD ✔️Fast and free worldwide shipping! ✔️Frequent special offers and discounts up to ...