Imitation and Limitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name Region System Mapper Savestate Powerpak

Name Region System Mapper Savestate Powerpak Savestate '89 Dennou Kyuusei Uranai Japan Famicom 1 YES Supported YES 10-Yard Fight Japan Famicom 0 YES Supported YES 10-Yard Fight USA NES-NTSC 0 YES Supported YES 1942 Japan Famicom 0 YES Supported YES 1942 USA NES-NTSC 0 YES Supported YES 1943: The Battle of Midway USA NES-NTSC 2 YES Supported YES 1943: The Battle of Valhalla Japan Famicom 2 YES Supported YES 2010 Street Fighter Japan Famicom 4 YES Supported YES 3-D Battles of Worldrunner, The USA NES-NTSC 2 YES Supported YES 4-nin Uchi Mahjong Japan Famicom 0 YES Supported YES 6 in 1 USA NES-NTSC 41 NO Supported NO 720° USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES 8 Eyes Japan Famicom 4 YES Supported YES 8 Eyes USA NES-NTSC 4 YES Supported YES A la poursuite de l'Octobre Rouge France NES-PAL-B 4 YES Supported YES ASO: Armored Scrum Object Japan Famicom 3 YES Supported YES Aa Yakyuu Jinsei Icchokusen Japan Famicom 4 YES Supported YES Abadox: The Deadly Inner War USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES Action 52 USA NES-NTSC 228 NO Supported NO Action in New York UK NES-PAL-A 1 YES Supported YES Adan y Eva Spain NES-PAL 3 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The France NES-PAL-B 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The Scandinavia NES-PAL-B 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The Spain NES-PAL-B 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt USA NES-NTSC 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt UK NES-PAL-A 1 YES Supported YES Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt -

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

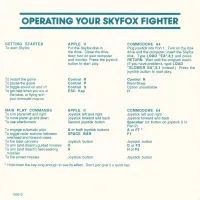

Skyfox Fighter

OPERATING YOUR SKYFOX FIGHTER GETTING STARTED APPLE II COMMODORE 64 To start Skyfox Put the Skyfox disk in Plug joystick into Port 1. Turn on the disk the drive. Close the drive drive and the computer; insert the Skyfox door; turn on your computer disk. Type LOAD "EA",8,1 and press and monitor. Press the joystick RETURN. Wait until the program loads. button to start play. (If you have problems, type LOAD "SLOWER EA",8,1 instead.) Press the joystick button to start play. To restart the game Control R Control R To pause the game Control P Run/Stop To toggle sound on and off Control S Option unavailable To get help when you are at ESC Key H the base, or flying with your computer map up MAIN PLAY COMMANDS APPLE II COMMODORE 64 To turn plane left and right Joystick left and right Joystick left and right To move plane up and down Joystick forward and back Joystick forward and back To use afterburners Second joystick button Spacebar (or button on joystick 2 in Port 2) To engage automatic pilot A or both joystick buttons AorF7* To toggle radar scanner between SPACE BAR F1 overhead and forward views To fire laser cannons Joystick button Joystick button To arm (and disarm) guided missiles G G or F3 To arm (and disarm) heat-seeking H H or F5 missiles To fire armed missiles Joystick button Joystick button • Hold down the key long enough to see' its effect. Don't just give it a quick tap. 103619 GETTING STARTED ATARI ST COMMODORE AMIGA To start Skyfox Put the Skyfox disk in After kickstarting your Amiga, insert the the drive and turn on the Skyfox disk in the drive. -

Understanding Visual Novel As Artwork of Visual Communication Design

MUDRA Journal of Art and Culture Volume 32 Nomor 3, September 2017 292-298 P-ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Understanding Visual Novel as Artwork of Visual Communication Design DENDI PRATAMA, WINNY GUNARTI W.W, TAUFIQ AKBAR Departement of Visual Communication Design, Fakulty of Language and Art Indraprasta PGRI. University, Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia [email protected] Visual Novel adalah sejenis permainan audiovisual yang menawarkan kekuatan visual melalui narasi dan karakter visual. Data dari komunitas pengembang Visual Novel (VN) Project Indonesia menunjukkan masih terbatasnya pengembang game lokal yang memproduksi Visual Novel Indonesia. Selain itu, produksi Visual Novel Indonesia juga lebih banyak dipengaruhi oleh gaya anime dan manga dari Jepang. Padahal Visual Novel adalah bagian dari produk industri kreatif yang potensial. Studi ini merumuskan masalah, bagaimana memahami Visual Novel sebagai karya seni desain komunikasi visual, khususnya di kalangan mahasiswa? Penelitian ini merupakan studi kasus yang dilakukan terhadap mahasiswa desain komunikasi visual di lingkungan Universitas Indraprasta PGRI Jakarta. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan masih rendahnya tingkat pengetahuan, pemahaman, dan pengalaman terhadap permainan Visual Novel, yaitu di bawah 50%. Metode kombinasi kualitatif dan kuantitatif dengan pendekatan semiotika struktural digunakan untuk menjabarkan elemen desain dan susunan tanda yang terdapat pada Visual Novel. Penelitian ini dapat menjadi referensi ilmiah untuk lebih mengenalkan dan mendorong pemahaman tentang Visual Novel sebagai karya seni Desain Komunikasi Visual. Selain itu, hasil penelitian dapat menambah pengetahuan masyarakat, dan mendorong pengembangan karya seni Visual Novel yang mencerminkan budaya Indonesia. Kata kunci: Visual novel, karya seni, desain komunikasi visual Visual Novel is a kind of audiovisual game that offers visual strength through the narrative and visual characters. -

Sample Iis Publication Page

https://doi.org/10.48009/2_iis_2020_185-195 Issues in Information Systems Volume 21, Issue 2, pp. 186-195, 2020 TOWARD A CONCEPTUAL MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING THE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG MMORPGS, GAMERS, AND ADD-ONS Qiunan Zhang, University of Memphis, [email protected] Yuelin Zhu, University of Memphis, [email protected] Colin G. Onita, San Jose State University, [email protected] M. Shane Banks, University of North Alabama, [email protected] Xihui Zhang, University of North Alabama, [email protected] ABSTRACT The consumption of video games has become a significant economic, cultural, and entertainment phenomenon worldwide. Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) are an important category of such games. In MMORPGs, gamers often play with add-ons to enhance their gaming experience. In previous research studies on MMORPGs, few of them have focused on the relationships among MMORPGs, gamers, and add-ons. This study presents a conceptual framework for use in addressing the following two questions: (1) What is the relationship between gamers and add-ons in MMORPGs? (2) How do factors (such as game quality and updates) impact gamers and add-ons and the relationship between them? In this paper, we develop a research model and describe a quantitative methodology that can be used to test and investigate the above questions. Implications for research and practice, as well as limitations and future research directions, are discussed. Keywords: MMORPGs, Motivations for Gaming, Gamers, Add-ons, Game Quality, Game Updates, Software Platform INTRODUCTION In 2017, video games became the most popular and profitable form of entertainment, producing an estimated revenue of $116 billion eclipsing TV and TV streaming services’ revenue of $105 billion (D’Argenio, 2018). -

What Way Is It Meant to Be Played?

What Way Is It Meant To Be Played? Florian Mihola March 2020 Abstract and home video game consoles digital inputs were the standard up until the “16-bit” era of the 1990s. The most commonly used interface between a Sony PlayStation, Nintendo 64 and Sega Saturn fi video game and the human user is a handheld are among the rst which brought with them ad- “game controller”, “game pad”, or in some occa- ditional analog controls—either at launch or as an sions an “arcade stick.” Directional pads, analog updated controller option. And even though mod- sticks and buttons—both digital and analog—are ern mass-market offerings include analog sticks linked to in-game actions. One or multiple simul- and analog triggers, digital buttons and directional taneous inputs may be necessary to communicate pads remain the ubiquitous fundamentals of input. the intentions of the user. Activating controls may The simple nature and widespread use of digital be more or less convenient depending on their po- inputs leads to a degree of interoperability: Game sition and size. In order to enable the user to per- software is not necessarily tied to a single game fi form all inputs which are necessary during game- controller—whether we interpret this as a speci c play, it is thus imperative to find a mapping be- model, a design and protocol available by different tween in-game actions and buttons, analog sticks, manufacturers, or a class of generic controllers— and so on. We present simple formats for such but can be enjoyed using a range of controllers, mappings as well as for the constraints on possi- provided they share at least some common char- ble inputs which are either determined by a phys- acteristics. -

Role Playing Games Role Playing Computer Games Are a Version Of

Role Playing Games Role Playing computer games are a version of early non-computer games that used the same mechanics as many computer role playing games. The history of Role Playing Games (RPG) comes out of table-top games such as Dungeons and Dragons. These games used basic Role Playing Mechanics to create playable games for multiple players. When computers and computer games became doable one of the first games (along with Adventure games) to be implemented were Role Playing games. The core features of Role Playing games include the following features: • The game character has a set of features/skills/traits that can be changed through Experience Points (xp). • XP values are typically increased by playing the game. As the player does things in the game (killing monsters, completing quests, etc) the player earns XP. • Player progression is defined by Levels in which the player acquires or refines skills/traits. • Game structure is typically open-world or has open-world features. • Narrative and progress is normally done by completing Quests. • Game Narrative is typically presented in a non-linear quests or exploration. Narrative can also be presented as environmental narrative (found tapes, etc), or through other non-linear methods. • In some cases, the initial game character can be defined by the player and the initial mix of skills/traits/classes chosen by the player. • Many RPGs require a number of hours to complete. • Progression in the game is typically done through player quests, which can be done in different order. • In Action RPGs combat is real-time and in turn-based RPGs the combat is turn-based. -

Commodore 64 Users Guide

INTRODUCTION Now that you've become more intimately involved with your Commo- dore 64, we want you to know that our customer support does not stop here. You may not know it, but Commodore has been in business for over 23 years. In the 1970's we introduced the first self-contained per- sonal computer (the PET). We have since become the leading computer company in many countries of the world. Our ability to design and manufacture our own computer chips allows us to bring you new and better personal computers at prices way below what you'd expect for this level of technical excellence. Commodore is committed to supporting not only you, the end user, but also the dealer you bought your computer from, magazines which publish how-to articles showing you new applications or techniques, and . importantly . software developers who produce programs on cartridge, disk and tape for use with your computer. We encourage you to establish or join a Commodore "user club" where you can learn new techniques, exchange ideas and share discoveries. We publish two separate magazines which contain programming tips, information on new products and ideas for computer applications. (See Appendix N). In North America, Commodore provides a "Commodore Information Network" on the CompuServe Information Service . to access this network, all you need is your Commodore 64 computer and our low cost VICMODEMtelephone interface cartridge (or other compatible modem). The following APPENDICEScontain charts, tables, and other informa- tion which help you program your Commodore 64 faster and more efficiently. They also include important information on the wide variety of Commodore products you may be interested in, and a bibliography listing of over 20 books and magazines which can help you develop your programming skills and keep you current on the latest information con- cerning your computer and peripherals. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Programme Edition

JOURNEE 13h00 - 18h00 WEEK END 14h00 - 19h00 JOURJOURJOUR Vendredi 18/12 - 19h00 Samedi 19/12 Dimanche 20/12 Lundi 21/12 Mardi 22/12 ThèmeThèmeThème Science Fiction Zelda & le J-RPG (Jeu de rôle Japonais) ArcadeArcadeArcade Strange Games AnimeAnimeAnime NES / Twin Famicom / MSXMSXMSX The Legend of Zelda Rainbow Islands Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles SC 3000 / Master System Psychic World Streets of Rage Rampage Super Nintendo Syndicate Zelda Link to the Past Turtles in Time + Sailor Moon Megadrive / Mega CD / 32X32X32X Alien Soldier + Robo Aleste Lunar 2 + Soleil Dynamite Headdy EarthWorm Jim + Rocket Knight Adventures Dragon Ball Z + Quackshot Nintendo 64 Star Wars Shadows of the Empire Furai no Shiren 2 Ridge Racer 64 Buck Bumble SaturnSaturnSaturn Deep Fear Shining Force III scénario 2 Sky Target Parodius Deluxe Pack + Virtual Hydlide Magic Knight Rayearth + DBZ Shinbutouden Playstation Final Fantasy VIII + Saga Frontier 2 Elemental Gearbolt + Gun Blade Arts Tobal n°1 Dreamcast Ghost Blade Spawn Twinkle Star Sprites Alice's Mom Rescue Gamecube F Zero GX Zelda Four Swords 4 joueurs Bleach Playstation 2 Earth Defense Force Code Age Commanders / Stella Deus Puyo Pop Fever Earth Defense Force Cowboy Bebop + Berserk XboxXboxXbox Panzer Dragoon Orta Out Run 2 Dead or Alive Xtreme Beach Volleyball Wii / Wii UWii U / Wii JPWii JP Fragile Dreams Xenoblade Chronicles X Devils Third Samba De Amigo Tatsunoko vs Capcom + The Skycrawlers Playstation 3 Guilty Gear Xrd Demon's Souls J Stars Victory versus + Catherine Kingdom Hearts 2.5 Xbox 360 / XBOX -

Anime: Manga: Ostalo

ANIME: One Piece Bamboo Blade Shigofumi in še več... MANGA: Hellsing Kamikaze Kaito Jeanne Gantz OSTALO: Loliconi z namenom Final Fantasy XII Fanfiction in še več... ス ロ han ち C lo ゃ S ん UVODNIK Kot obljubljeno, sestavljena je nova številka SloChana; revije, s katero ljubiteljem animejev in mang poskušamo prikazati za- nimivosti in novosti tovrstne scene. V prejšnji številki smo se dotaknili osnov, saj smo spoznali, kaj »anime« sploh je, v tokratnem uvodniku pa se bomo posvetili nekaterim novostim na SloAnime portalu, prenovljeni uradni strani slochan.com in navezi z multime- dijsko revijo »Medijska vzgoja in produkcija«. Kot smo že izvedeli v prejšnji številki, je SloAnime.org eden izmed redkih portalov v Sloveniji, ki navdušuje, razširja in informira sloven- ske ljubitelje z novostmi iz japonske scene o animejih, mangah, igrah in tudi igranih filmih. Diskusije na forumu so ključnega pomena, saj je kvalitetna diskusija merilo uspešnosti in navduševanja tudi med ljubitelji. Od prejšnje številke je minilo že štiri mesece in portal je imel v tem času kar precej zanimivih akcij, ki so poskušale animeje še približati vsem oboževalcem. Ustanovljen je bil poseben blog z imenom »Sekai« (slo: svet), katerega namen je sočasno pisanje več blogerjev o več različnih tema- tikah, ki se ne ne tičejo le animejev in mang. V današnjem času je bloganje postalo zelo popularno in v Sloveniji obstaja nekaj posebnih blogerskih agregatov, ki v ospredje postavljajo najboljše vpise na uporabniških blogih. Ker je DjJuvan s svojim blogom že od lanskega leta do danes naredil precej uspešnih prelomnic in se s svojimi animejsko usmerjenimi vsebinami pojavil na prvih straneh znanih agregatov, se mu je kmalu pridružilo k pisanju še nekaj animejskih navdušencev in počasi se je porodila ideja, da bi se pisalo skupen, obširnejši blog, kjer bi sočasno pisali zanimive vnose o splošnih tematikah in hkrati navduševali z animejsko usmerjenimi zanimivostmi. -

![When High-Tech Was Low-Tech : a Retrospective Look at Forward-Thinking Technologies [Multiple Exhibits]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4438/when-high-tech-was-low-tech-a-retrospective-look-at-forward-thinking-technologies-multiple-exhibits-614438.webp)

When High-Tech Was Low-Tech : a Retrospective Look at Forward-Thinking Technologies [Multiple Exhibits]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Library and Community-based Exhibits Library Outreach 9-1-2003 When High-Tech was Low-Tech : A Retrospective Look at Forward-Thinking Technologies [Multiple exhibits] James Anthony Schnur, Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/npml_outreach_exhibits Scholar Commons Citation Schnur,, James Anthony, "When High-Tech was Low-Tech : A Retrospective Look at Forward-Thinking Technologies [Multiple exhibits]" (2003). Library and Community-based Exhibits. 43. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/npml_outreach_exhibits/43 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Outreach at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library and Community-based Exhibits by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When High-Tech was Low-Tech A Retrospective Look at Forward-Thinking Technologies Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg When High-Tech was Low-Tech When High-Tech was Low-Tech When High-Tech was Low-Tech The development of transistors after By the late 1970s, early “personal Before the widespread use of “floppy” World War II allowed manufacturers to computers” and game systems began to disks (in both 5¼ and 8 inch formats), build smaller, more sophisticated, and appear in homes. One of the most many early personal computers used less expensive devices. No longer did popular games of this period came from tape drives. “Personal computer consumers have to worry about Atari. This Ultra-Pong console, cassettes” usually held about 64,000 purchasing expensive tubes for heavy, released by Atari in 1977, included bytes of data and could take up to 30 bulky radios and televisions.