Africa's Soviet Ballet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Citizens and Subjects: Dance and Resistance in Twenty-First Century Mozambique Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1w33f4s5 Author Montoya, Aaron Tracy Publication Date 2016 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ PERFORMING CITIZENS AND SUBJECTS: DANCE AND RESISTANCE IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY MOZAMBIQUE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ANTHROPOLOGY with an emphasis in Visual Studies by Aaron Montoya June 2016 The Dissertation of Aaron Montoya is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Shelly Errington, Chair ____________________________________ Professor Carolyn Martin-Shaw ____________________________________ Professor Olga Nájera-Ramírez ____________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ____________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Aaron T. Montoya 2016 Table of Contents Abstract iv Agradecimientos vi Introduction 1 1. Citizens and Subjects in Portuguese Mozambique 20 2. N’Tsay 42 3. Nyau 84 4. Um Solo para Cinco 145 5. Feeling Plucked: Labor in the Cultural Economy 178 6. Conclusion 221 Bibliography 234 iii Abstract Performing Citizens and Subjects: Dance and Resistance in Twenty-First Century Mozambique Aaron Montoya This dissertation examines the politics and economics of the cultural performance of dance, placing this expressive form of communication within the context of historic changes in Mozambique, from the colonial encounter, to the liberation movement and the post-colonial socialist nation, to the neoliberalism of the present. The three dances examined here represent different regimes, contrasting forms of subjectivity, and very different relations of the individual to society. -

Convert Finding Aid To

Fred Fehl: A Preliminary Inventory of His Dance Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Fehl, Fred, 1906-1995 Title: Fred Fehl Dance Collection 1940-1985 Dates: 1940-1985 Extent: 122 document boxes, 19 oversize boxes, 3 oversize folders (osf) (74.8 linear feet) Abstract: This collection consists of photographs, programs, and published materials related to Fehl's work documenting dance performances, mainly in New York City. The majority of the photographs are black and white 5 x 7" prints. The American Ballet Theatre, the Joffrey Ballet, and the New York City Ballet are well represented. There are also published materials that represent Fehl's dance photography as reproduced in newspapers, magazines and other media. Call Number: Performing Arts Collection PA-00030 Note: This brief collection description is a preliminary inventory. The collection is not fully processed or cataloged; no biographical sketch, descriptions of series, or indexes are available in this inventory. Access: Open for research. An advance appointment is required to view photographic negatives in the Reading Room. For selected dance companies, digital images with detailed item-level descriptions are available on the Ransom Center's Digital Collections website. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gift, 1980-1990 (R8923, G2125, R10965) Processed by: Sue Gertson, 2001; Helen Adair and Katie Causier, 2006; Daniela Lozano, 2012; Chelsea Weathers and Helen Baer, 2013 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Fehl, Fred, 1906-1995 Performing Arts Collection PA-00030 Scope and Contents Fred Fehl was born in 1906 in Vienna and lived there until he fled from the Nazis in 1938, arriving in New York in 1939. -

Danny Daniels Papers LSC.1925

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8tm7h6q No online items Finding Aid for the Danny Daniels Papers LSC.1925 Finding aid prepared by Douglas Johnson, 2017; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 October 16. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Danny Daniels LSC.1925 1 Papers LSC.1925 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Danny Daniels papers Creator: Daniels, Danny Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1925 Physical Description: 36.2 Linear Feet(61 boxes, 3 cartons, 2 shoe boxes, 16 flat boxes, 2 oversize flat boxes) Date (inclusive): 1925-2004 Date (bulk): 1947-2004 Abstract: Danny Daniels was a tap dancer, choreographer, and entrepreneur. The collection consists primarily of material from his long career on stage and in film and television. There are also records from his eponymous dance school, as well as other business ventures. There is a small amount of personal material, including his collection of theater programs spanning five decades. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are primarily in English, with a very small portion in French and Italian. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements COLLECTION CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisua materials. -

Here from There—Travel, Television and Touring Revues: Internationalism As Entertainment in the 1950S and 1960S

64 Jonathan Bollen Flinders University, Australia Here from There—travel, television and touring revues: internationalism as entertainment in the 1950s and 1960s Entertainments depicting national distinctions attracted Australian audiences in the 1950s and 1960s. Touring revues from overseas afforded opportunities to see the nations of the world arrayed on the stage. Each of the major producers of commercial entertainments in Australia imported revues from Europe, Africa, the Americas and East Asia. Like their counterparts in Hong Kong and Singapore, entrepreneurs in Australia harnessed an increasing global flow of performers, at a time when national governments, encouraged by their participation in the United Nations, were adopting cultural policies to foster national distinction and sending troupes of entertainers as cultural ambassadors on international tours. In this article the author explores the significance of internationalist entertainment in mid-20th century Australia, focusing on Oriental Cavalcade, an “East Meets West” revue from 1959 which toured with performers from Australia and Asia. At a time when television viewing was becoming a domestic routine and international aviation was becoming an affordable indulgence, producers of internationalist entertainments offered audiences in the theatre experiences of being away from home that were akin to tourism and travel beyond the domestic scene. Jonathan Bollen is a Senior Lecturer in Drama, Flinders University, Australia Keywords: variety, revue, aviation, tourism, travel, television, internationalism desire to create a national theatre for Australia gathered momentum A in the late-1940s and eventually gained traction.1 Government support for the performing arts was introduced with the establishment of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust in 1954 and the subsequent founding of new national opera, theatre and ballet companies and the National Institute of Dramatic Art, while government investment in venues for the performing arts Popular Entertainment Studies, Vol. -

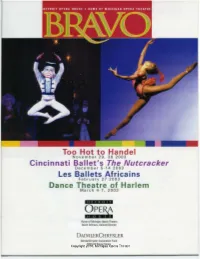

Too Hot to Handel Cincinnati Ballet's the Nutcracker Les Ballets

Too Hot to Handel November 29, 30 2003 Cincinnati Ballet's The Nutcracker December 5-14 2003 Les Ballets Africains February 27 2003 Dance Theatre of Harlem March 4-7, 2003 DETROIT Home of Michigan Opera Theatre David DiChiera, General Director DAIMLERCHRYSLER DaimlerChrysler Corporation Fund Copyright 2010,2003-04 Michigan Dance Series Opera Theatre No one can guarantee success. But knowing how to rehearse for it certainly helps. With over 250 relationship managers dedicated to one-on -one service, a full array of the latest financial products, and an emphasis on helping local businesses succeed, the Standard Federal Commercial Banking team makes sure your needs are always front and center. For more information, call 1-248-822-5402 or visit standardfede ralbank.c om . True Possibility. Standard Federal Bank ABN AMRO standardfederalbank.com ©2003 Standard Federal BankNA Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre Sur ender to Love DETROIT OPERA HOUSE . HOME OF MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE ]B~VO 2003-2004 The Official Magazine of the Detroit Opera House BRAVO IS A MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE PUBLICATION Winer CONTRIBUTORS Dr. David DiChiera, General Director Matthew S. Birman, Editor Laura Wyss cason Michigan Opera Theatre Staff PUBLISHER ON STAGE Live Publishing Company TOO HOT TO HANDEL. .4 Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction Program ............ .5 Blink Concept &: Design, Inc. Production Artist Profiles .................. ... ...... .6 Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales Rackham Symphony Choir ..... .. .............. .7 Marygrove College Chorale and Soulful Expressions Ensemble 7 Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford Medical Center. Too Hot to Handel Orchestra ... .... .... ........ 7 THE NUTCRACKER .9 Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. -

Lewis Segal Collection of Dance and Theater Materials, 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8c24wzf No online items Lewis Segal Collection of Dance and Theater Materials, 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009 Preliminary processing by Andrea Wang; fully processed by Mike D'Errico in 2012 in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Jillian Cuellar; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. The processing of this collection was generously supported by Arcadia funds. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Lewis Segal Collection of Dance 1890 1 and Theater Materials, 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009 Descriptive Summary Title: Lewis Segal Collection of Dance and Theater Materials Date (inclusive): 1902-2011; Bulk, 1970-2009 Collection number: 1890 Collector: Segal, Lewis Extent: 24 record cartons (24 linear ft.) Abstract: Lewis Segal is a performing arts critic who has written on various topics related to the performing arts, from ballet to contemporary dance and musicals. He began working as a freelance writer in the 1960s for a number of publications, including the Los Angeles Times, Performing Arts magazine, the Los Angeles Free Press, Ballet News, and High Performance magazine. He joined the staff of the Los Angeles Times in 1976. From 1996 to 2008 he held the full-time position of chief dance critic, writing full features and reviews on dance companies and performing arts organizations from around the world. -

University Musical Society Les Ballets Africains

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY LES BALLETS AFRICAINS The African Ballet of the Republic of Guinea Italo Zambo, Artistic Director Hamidou Bangoura, Technical Director Mohamed Kemoko Sano, Choreographer Thursday Evening, October 17, 1991, at 7:00 Friday Evening, October 18, 1991, at 8:00 Power Center for the Performing Arts Ann Arbor, Michigan Female Dancers Manana Cisse Marie Bangoura Hawa Conde Diely Kanni Diawara Mayeni Camara Fadima Traore Naitou Camara Macire Souare Manama Toure Mouminata Camara Maimouna Diawara M'mah Toure Male Dancers Sekou II Conde Aboubacar II Camara Sekou Sylla Bangaly Bangoura Mamadouba Camara Papa Cherif Haidara Yamoussa Soumah Mamadouba Soumah Aboubacar Bangoura Moustapha Bangoura Hamidou Koivogui Amadou Dioulde Diallo Musicians/Dancers Gbanworo Keita Laurent Camara Mamadi Mansare Fode Kalissa Seny Toure Mohamed Sylla Koca Sale Dioubate Younoussa Camara Mohamed Lamine Sylla Ibrahima Gueye, Administrator; Ibrahima Conte, Regisseur; Tim Speechley, Company Manager; Marc Napoletano, Tour Manager; Tim Moore/Papyvore, Graphic Design/Print; Rikki Stein, Pan African Arts Management Les Ballets Africains wishes to thank the French Ministry of Co-operation through its Cul tural Action Program in Guinea; the Arts Council of Great Britain's International Initiatives Fund; SOGUICAF S. A. of Kissidougou in Guinea and Quick Reek & Smith (Coffee) Lim ited of London; and the Guinean Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism and staff, in cluding the Musee Nationale Sandervalia. Les Ballets Africains appears by arrangement with Columbia Artists Festivals, a division of Columbia Artists Management, Inc., New York. These concerts are supported by Arts Midwest members and friends in partnership with Dance on Tour, the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Imaginings of Africa in the Music of Miles Davis by Ryan

IMAGININGS OF AFRICA IN THE MUSIC OF MILES DAVIS BY RYAN S MCNULTY THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Music with a concentration in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Advisor: Associate Professor Gabriel Solis Abstract Throughout jazz’s history, many American jazz musicians have alluded to Africa using both musical and extramusical qualities. In musicological literature that has sought out ties between American jazz and Africa, such as Ingrid Monson’s Freedom Sounds (2007) and Robyn Kelly’s Africa Speaks, America Answers (2012), the primary interest has thus far been in such connections that occurred in the 1950s and early 1960s with the backdrop of the Civil Rights movement and the liberation of several African countries. Among the most frequently discussed musicians in this regard are Art Blakey, Max Roach, and Randy Weston. In this thesis, I investigate the African influence reflected in the music of Miles Davis, a musician scantly recognized in this area of jazz scholarship. Using Norman Weinstein’s concept of “imaginings,” I identify myriad ways in which Davis imagined Africa in terms of specific musical qualities as well as in his choice of musicians, instruments utilized, song and album titles, stage appearance, and album artwork. Additionally (and often alongside explicit references to Africa), Davis signified African-ness through musical qualities and instruments from throughout the African diaspora and Spain, a country whose historical ties to North Africa allowed Davis to imagine the European country as Africa. -

January / February

CONCERT & DANCE LISTINGS • CD REVIEWS FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 7 Number 1 January-February 2007 THESOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING & OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTS IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers MARIAMARIA MULDAURMULDAUR GIVESGIVES DYLANDYLAN AA SHOTSHOT OFOF LOVELOVE inside this issue: BY REX BUTTERS inside this issue: aria Muldaur’s latest release, Heart of Mine: Love Songs of Bob Dylan adds PraisingPraising PeacePeace another notch on an enviable creative upswing. A bona fide national treasure, AA TributeTribute toto PaulPaul RobesonRobeson her artistic momentum since the nineties has yielded a shelf full of CDs covering M roots music, blues, love songs, and Peggy CalifoniaCalifonia IndianIndian Lee, each with Muldaur’s faultless aesthetics overseeing the production as well. Graciously, she took a break from Tribal Culture her relentless performance-rehearsal-recording schedule Tribal Culture to chat about her recent projects. FW: It was great to hear you back on fiddle on You Ain’t Goin Nowhere, a very exuberant reading of that song. PLUS:PLUS: MM: Thank you. We just kind of got down with a low down Cajun hoedown on the whole thing. It reminded me RossRoss Altman’sAltman’s of the kind of stuff the Band was playing over at Big Pink when we all lived in Woodstock. It had that vibe to it. Bob HowHow CanCan II KeepKeep FromFrom TalkingTalking [Dylan], in the last ten years or so, every time I would see him backstage at a gig, he started asking me, “Hey are you ever playing your fiddle anymore?” And I’d say, oh no, && muchmuch more...more.. -

Films on Africa: an Educators Guide to 16Mm Films Available in The

DOCUMENT NESUME ED 127 246 -48 SO 009 356 AUTHOR Gerzoff, Sheila, Comp.; And Others TITLE Films on Africa: An Educators Guide to 16m Films Available in the Midwest. INSTITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison. African Studies Program. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHBW), Washington, D.C4 PUB DATE Dec 74 NOTE 74p.; Not available in hard copy due to too small type AVAILABLE FROMAfrican Studies Program, University of Wisconsin, j 1450 Van Hise Hall, 1220Linden Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 ($1.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0..83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *African Culture; *African History; Catalogs; Developing Nations; Elementary Seccndary Education; *Filmographies; *Films; foreign Countries'; Higher Education; Indexes (Locaters); Instructional Films; International Education; Political Science; *Resource i Guides; Single Concept Films; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Africa; United States (Midwest) ABSTRACT This is a compendium of almost 700 16mm films about Africa. The guide lists existing resources that are readily available in the Midwest to educators in elementary and secondary schools, colleges, universities, and communities. Selected were films being distributed by nonprofit educational, religious, and commercial distributors; films from African embassies and United Nations missions; documentary and feature films; and films cf both very high and low quality. Stereotypical, insulting, or biased films are included as illustrative of differing political orientations and conflicts in Africa. Chapter one lists the films by topic which some college-level Africanists use, and it offers some evaluation of films. Chapter two lists available films by title and provides multiple sources for each by code along with their 1974 prices. Descriptive information and appropriate grade level are provided if known. -

Dancing the Cold War an International Symposium

Dancing the Cold War An International Symposium Sponsored by the Barnard College Dance Department and the Harriman Institute, Columbia University Organized by Lynn Garafola February 16-18, 2017 tContents Lynn Garafola Introduction 4 Naima Prevots Dance as an Ideological Weapon 10 Eva Shan Chou Soviet Ballet in Chinese Cultural Policy, 1950s 12 Stacey Prickett “Taking America’s Story to the World” Ballets: U.S.A. during the Cold War 23 Stephanie Gonçalves Dien-Bien-Phu, Ballet, and Politics: The First Sovviet Ballet Tour in Paris, May 1954 24 Harlow Robinson Hurok and Gosconcert 25 Janice Ross Outcast as Patriot: Leonid Yakobson’s Spartacus and the Bolshoi’s 1962 American Tour 37 Tim Scholl Traces: What Cultural Exchange Left Behind 45 Julia Foulkes West and East Side Stories: A Musical in the Cold War 48 Victoria Phillips Cold War Modernist Missionary: Martha Graham Takes Joan of Arc and Catherine of Siena “Behind the Iron Curtain” 65 Joanna Dee Das Dance and Decolonization: African-American Choreographers in Africa during the Cold War 65 Elizabeth Schwall Azari Plisetski and the Spectacle of Cuban-Soviet Exchanges, 1963-73 72 Sergei Zhuk The Disco Effect in Cold-War Ukraine 78 Video Coverage of Sessions on Saturday, February 18 Lynn Garafola’s Introduction Dancers’ Roundatble 1-2 The End of the Cold War and Historical Memory 1-2 Alexei Ratmansky on his Recreations of Soviet-Era Works can be accessed by following this link. Introduction Lynn Garafola Thank you, Kim, for that wonderfully concise In the Cold War struggle for hearts and minds, – and incisive – overview, the perfect start to a people outside the corridors of power played a symposium that seeks to explore the role of dance huge part. -

The Politics of Representation and Transmission in the Globalization of Guinea's Djembé

THE POLITICS OF REPRESENTATION AND TRANSMISSION IN THE GLOBALIZATION OF GUINEA'S DJEMBÉ by Vera H. Flaig A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Emeritus Judith O. Becker, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Christi-Anne Castro, Co-Chair Associate Professor Vanessa Helen Agnew Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett Associate Professor Mbala D. Nkanga © Vera Helga Flaig All rights reserved 2010 Dedication To Deborah Anne Duffey the wind beneath my wings; Herdith Flaig who encouraged me to be strong and independent; Erhardt Flaig who always believed in me; and Rainer Dörrer who gave his life for the djembé. ii Acknowledgements Given the scope of the research that preceded the writing of this dissertation, there are many people to thank. Of all the individuals I met in Germany, Guinea, and across the United States I am sure to miss a few. There are not enough pages to be able to name all people who have: helped me find directions, connect with informants, provided me a place to stay, shared their food, and compared notes in a djembé workshop. To all who remain nameless, I thank you for making this project possible. I would like to thank the Rackham Graduate School and the School of Music, Theatre and Dance at the University of Michigan for generously funding my graduate work. I was honored to receive a Board of Regents Fellowship as well as several Teaching Assistantships which helped me to reach candidacy. I was also honored to receive the Glen McGeoch memorial Scholarship during my final semester as a Graduate Student Instructor.