Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

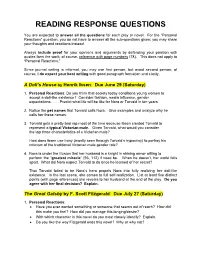

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

Canterbury Tales III CD Booklet

Henry James CLASSIC FICTION The Wings of the Dove Read by William Hope NA339012 1 ‘She waited, Kate Croy, for her father to come in…’ 14:22 2 Mrs Lowder (née Manningham) – Aunt Maud – at Lancaster Gate 7:51 3 ‘Merton Densher, who passed the best hours of each night...’ 14:31 4 ‘Shortly afterwards, in Mrs Lowder’s vast drawing room, he awaited her, at her request...’ 14:17 5 The two ladies – Milly Theale and Mrs Susan Stringham 14:14 6 Lord Mark – very neat, very light, with a double eye-glass 3:48 7 Mrs Stringham drinks deep at Lancaster Gate 4:32 8 Social circles intermingle 5:56 9 The great historic house at Matcham 1:32 10 ‘Have you seen the picture in the house…’ 5:16 11 Ten minutes with Sir Luke Strett 11:33 12 A chance meeting at the National Gallery 4:34 13 Kate Croy and Merton Densher converse 4:09 14 An invitation to Mrs Lowder 5:13 15 Milly Theale and Merton Densher 7:42 16 Susan Stringham visits Mrs Lowder at Lancaster Gate 9:56 2 17 Sir Luke gives his advice 2:57 18 In Venice – high florid rooms, palatial chambers 11:10 19 Densher’s hotel – in an independent quartiere far down the Grand Canal 7:35 20 Merton and Kate – in the middle of Piazza San Marco 6:10 21 Five minutes with Mrs Stringham before dinner 13:13 22 In the aftermath of Kate – questions from Milly 8:28 23 Walking through narrow ways 6:16 24 Merton Densher and Susan Stringham 10:29 25 Sir Luke Stett arrives 4:57 26 In the December dusk of Lancaster Gate 7:07 27 On the edge of Christmas 3:33 28 In Sir Luke Strett’s great square 25:30 Total time: 3:57:39 3 Henry James The Wings of the Dove Henry James (1843-1916) was born in New preoccupy James for the whole of his career: York, the son of Henry James senior, a the impact of a sophisticated European distinguished American philosopher. -

Andover-1913.Pdf (7.550Mb)

TOWN OF ANDOVER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Receipts and Expenditures ««II1IUUUI«SV FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JANUARY 13, 1913 ANDOVER, MASS. THE ANDOVER PRESS *9 J 3 CONTENTS Almshouse Expenses, 7i Memorial Day, 58 Personal Property at, 7i Memorial Hall Trustees' Relief of, out 74 Report, 57, 121 Repairs on, 7i Miscellaneous, 66 Superintendent's Report, 75 Moth Suppression, 64 Animal Inspector, 86 Notes Given, Appropriations, 1912, 17 58 Art Gallery, 146 Notes Paid, 59 Assessors' Report 76 Overseers of Poor, 69 Assets, 93 Park Commissioner, 56 Auditor's Report, 105 Park Commissioners' Report 81 Board of Health, 65 Playstead, 55 Board of Public Works, Appen dix, Police, 53, 79 Sewer Maintenance, 63 Sewer Sinking Funds, 63 Printing and Stationery, 55 Water Maintenance, 62 Punchard Free School, Report Water Construction, 63 of Trustees, 101 Water Sinking Funds, 63 Repairs on old B. V. School, 68 Bonds, Redemption of, 62 Schedule of Town Property, 82 Collector's Account, 89 Schoolhouses, 29 Cornell Fund, 88 Schools, 23 County Tax, 56 School Books and Supplies, 3i Daughters of Revolution 68 Dog Tax 56 Selectmen's Report, 23 Dump, care of 58 Sidewalks, 42 Earnings Town Horses, 48 Soldiers' Relief, 74 Elm Square Improvements, 43 Snow, Removal of, 43 Fire Department, 51 77 Spring Grove Cemetery, 57, 87 Haggett's Pond Land, 68 State Aid, 74 Hay Scales, 58 State Tax, 55 Highways and Bridges, 33 Street Lighting, 50 Highway Surveyor, 46 Street List, 109 Horses and Drivers, 4i Town House, 54 Insurance, 63 Town Meeting, 7 Interest on Notes and Funds, 59 Town Officers, Liabilities, ior 4, 49 Town Warrant, 117 Librarian's Report, 125 Account, Macadam, 35 Treasurer's 93 Andover Street, 37 Tree Warden, 50 Salem Street, 39 Report, 85 TOWN OFFICERS, 1912 Selectmen, Assessors and Overseers of the Poor HARRY M. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

ANALYSIS the Wings of the Dove (1902) Henry James (1843-1916)

ANALYSIS The Wings of the Dove (1902) Henry James (1843-1916) “James, somewhat hampered by the prudery imposed on him by English social conventions, devised a complicated and rather bizarre plot. Kate Croy is in love with a journalist, Merton Densher, but will not marry him until he is financially secure. She becomes acquainted with Milly Theale, an American heiress, and learns that an ailment from which Milly is suffering dooms her to an early death. Kate concocts a fantastic scheme; without revealing her motive she tells Densher to take an interest in Milly, who promptly falls in love with him and makes a will leaving him all her money. But an English lord, who himself had the notion of marrying Milly and inheriting her wealth, learns of the scheme and reveals it to Milly. She dies soon after and Densher receives a large check for his legacy. He offers to marry Kate if she will consent to let him destroy the check, but she demands a recompense: he must swear he is not in love with Milly’s memory. This he refuses to do; and the deal is off. The book is regarded as a culmination of James’s final style, along with The Ambassadors and The Golden Bowl; for many readers its difficulties are redeemed by Milly’s charm and fortitude. An opera based on the novel was produced in New York (1961).” Max J. Herzberg & staff The Reader’s Encyclopedia of American Literature (Crowell 1962) “Kate Croy, daughter of an impoverished English social adventurer, is in love with Merton Densher, a London journalist, and they become secretly engaged, although she will not marry him while he is without wealth. -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Notes

How to Read Literature Like a Professor (Thomas C. Foster) Notes Introduction Archetypes: Faustian deal with the devil (i.e. trade soul for something he/she wants) Spring (i.e. youth, promise, rebirth, renewal, fertility) Comedic traits: tragic downfall is threatened but avoided hero wrestles with his/her own demons and comes out victorious What do I look for in literature? - A set of patterns - Interpretive options (readers draw their own conclusions but must be able to support it) - Details ALL feed the major theme - What causes specific events in the story? - Resemblance to earlier works - Characters’ resemblance to other works - Symbol - Pattern(s) Works: A Raisin in the Sun, Dr. Faustus, “The Devil and Daniel Webster”, Damn Yankees, Beowulf Chapter 1: The Quest The Quest: key details 1. a quester (i.e. the person on the quest) 2. a destination 3. a stated purpose 4. challenges that must be faced during on the path to the destination 5. a reason for the quester to go to the destination (cannot be wholly metaphorical) The motivation for the quest is implicit- the stated reason for going on the journey is never the real reason for going The real reason for ANY quest: self-knowledge Works: The Crying of Lot 49 Chapter 2: Acts of Communion Major rule: whenever characters eat or drink together, it’s communion! Pomerantz 1 Communion: key details 1. sharing and peace 2. not always holy 3. personal activity/shared experience 4. indicates how characters are getting along 5. communion enables characters to overcome some kind of internal obstacle Communion scenes often force/enable reader to empathize with character(s) Meal/communion= life, mortality Universal truth: We all eat to live, we all die. -

Henry James and Romantic Revisionism: the Quest for the Man of Imagination in the Late Work

HENRY JAMES AND ROMANTIC REVISIONISM: THE QUEST FOR THE MAN OF IMAGINATION IN THE LATE WORK A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (OF ENGLISH ) By Daniel Rosenberg Nutters May 2017 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Alan Singer, English Steve Newman, English Robert L. Caserio, External Member, Pennsylvania State University Jonathan Arac, External Member, University of Pittsburgh © Copyright 2017 by Daniel Rosenberg Nutters All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This study situates the late work of Henry James in the tradition of Romantic revisionism. In addition, it surveys the history of James criticism alongside the academic critique of Romantic-aesthetic ideology. I read The American Scene, the New York Edition Prefaces, and other late writings as a single text in which we see James refashion an identity by transforming the divisions or splits in the modern subject into the enabling condition for renewed creativity. In contrast to the Modernist myth of Henry James the master reproached by recent scholarship, I offer a new critical fiction – what James calls the man of imagination – that models a form of selfhood which views our ironic and belated condition as a fecund limitation. The Jamesian man of imagination encourages the continual (but never resolvable) quest for a coherent creative identity by demonstrating how our need to sacrifice elements of life (e.g. desires and aspirations) when we confront tyrannical circumstances can become a prerequisite for pursuing an unreachable ideal. This study draws on the work of post-war Romantic revisionist scholarship (e.g. -

2010 Exam Day Lunch Schedule

Ontario H. S. 2016-17 English Department Reading Material Freshmen Books: Summer: Animal Farm School Year: To Kill a Mockingbird Romeo and Juliet The Odyssey Sophomore Books Summer: Of Mice and Men ...alternative The Pearl Honors: Summer: The Hunger Games by Collins Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card School Year: Dover Thrift edition of Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton Dover Thrift edition of Bullfinch's Mythology Julius Caesar by Shakespeare Lord of the Flies by William Golding Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes Twelve Angry Men by Reginald Rose A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah Junior Books: Summer: Celia Garth by Gwen Bristow Recommended- not required: Celebrate Liberty! Famous Patriotic Speeches and Sermons Complied by David Barton Thomas Paine’s Common Sense School Year: 1984 by Orwell The Scarlet Letter by Hawthorne The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Twain The Athena Project by Brad Thor Anthem by Ayn Rand Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand Salem’s Lot by Stephen King Advanced Placement: The Language of Composition: Reading. Writing. Rhetoric by Shea(2013) 5 Steps to a 5 AP English Language : McGraw Hill American Literature opposite College Credit +: Celia Garth by Gwen Bristow Senior Books: Summer: No Fear Shakespeare: Hamlet by Shakespeare School Year: Dover Thrift edition of Daisy Miller by James Dover Thrift Edition of A Doll’s House by Ibsen Dover Thrift Edition of Metamorphosis by Kafka Dover Thrift edition of The Importance of Being Ernest by Wilde Novel of Choice from the Multi-Genre book list (200+ books) Textbook: Literature -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47117-6 — the American Scene Henry James , Edited by Peter Collister Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47117-6 — The American Scene Henry James , Edited by Peter Collister Index More Information INDEX Abbey, Edwin Austin, 268, 291 n. 2 Augustine, St, 92 n. 15, 464 n. 40, 466 n. 43 The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Avilés, Pedro Menéndez de, 466 n. 43 Grail, 268 n. 53 Acropolis, Athens, 375 Bache, Richard, 312 n. 37 Acts of the Apostles, 159 n. 45 Bacon, Henry Adam, Robert, 285 n. 26 Franklin at Home at Philadelphia, 312 n. 38 Adams, Henry, 317 n. 47, 345 n. 1, 346 n. 3, 348 Baedeker, Karl, 467 n. 47 n. 8, 354 n. 19 Guide, 467 Adams, Marian Hooper, 346 n. 3, 353 n. 16, Baghdad, 230 354–5, nn. 18, 19 Balzac, Honoré de, 38 n. 60 Adler, Jacob, 220 n. 12 Barbizon school, 165 n. 59 Adriatic Sea, 220 Barnum, P.T., 92 n. 18 Aeschylus, 57 n. 93 Bartholdi, Frédéric Auguste Agassiz, Louis, 380 n. 7 Fountain of Light and Water, 371 n. 43 Alcott, Amos Bronson, 275 n. 5 Baudelaire, Charles, 122 n. 71 American Academy of Arts, 376 n. 1 Beaux, Cecilia, 314 n. 40 American Civil War, 72, 188, 245, 325–326, Beecher, Henry Ward, 50 n. 84 367 n. 33, 376 n. 1, 379–80, 381 n. 10, Benedict, Clara Woolson, 114 n. 57, 430 n. 39 382 n. 11, 384, 386 n. 16, 388, 391 n. 27, Benedict, Clare, 114 n. 57 393–4, 413, 422 n. 22, 428 n. 36, Benson, Frank W., 37 n. 58 467 n. -

The Extensive Use of Imagery and Symbolism in the Depiction of Moral Ambiguity in James’S the Wings of the Dove and the Golden Bowl

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 2006 / Cilt: 23 / Say›: 1 / ss. 1-18 The Extensive Use of Imagery and Symbolism in the Depiction of Moral Ambiguity in James’s The Wings of the Dove and The Golden Bowl Nursel İÇÖZ* Özet Bu makalede Henry James’in The Wings of the Dove ve The Golden Bowl adl› romanlar›nda iyilik ve kötülük kavramlar› incelenecektir. Makalenin amac›, bu kavramlar›n temelinin insan ilişkileri ve karakterlerin d›ş dünya ile olan ilişkilerinde yatt›ğ›n›, ve yazar›n, kulland›ğ› simgeler ve imgeler yoluyla bu kavramlar› güçlendirdiğini ortaya koymakt›r. Her iki romanda da materyalizm çok önemli bir yere sahip olmas›na rağmen karakterlerin duygular›na ve düş güçlerine de ayn› derecede yer verilmiş ve iyilik ve kötülük kavramlar›n›n net bir biçimde ay›rt edilemiyeceği gösterilmiştir. Bu aç›lardan iki roman› bir bütünün parçalar› olarak görmek mümkündür. Anahtar sözcükler: iyilik, kötülük, simgeler, imgeler, materyalizm, insan ilişkileri Abstract The article aims to analyze the concepts of good and evil in Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove and The Golden Bowl. The main argument is that James’s extensive use of symbolism and imagery helps to reinforce the illustration of these concepts and that good and evil seem to reside in human relations and the characters’ relatedness to the world outside themselves. Although materialism occupies a central role in these novels, the characters’ feelings and imagination are also probed into with the result that the interdependence of good and evil is revealed. The two novels can be seen as two parts of a single unit in these respects. -

The Patriarchal Society's Responses to Daisy Miller's Performances in James' Daisy Miller

THE PATRIARCHAL SOCIETY’S RESPONSES TO DAISY MILLER’S PERFORMANCES IN JAMES’ DAISY MILLER A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Attainment of a Sarjana Sastra Degree in English Literature by Yunita M. Salka 05211141004 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE STUDY PROGRAM ENGLISH EDUCATION DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS YOGYAKARTA STATE UNIVERSITY 2013 MOTTOS When life gives you a hundred reasons to cry, show life that you have a thousand reasons to smile. (anonymous) Because, Every face tells a story, every smile brings happiness (Maya Angelou) Finally, To those who see with loving eyes, life is beautiful. To those who speak with tender voices, life is peaceful. To those who help with gentle hands, life is full. And to those who care with compassionate hearts, life is good beyond all measure. (anonymous) v DEDICATION This thesis is lovingly dedicated to: • My dearest Mom and Dad • My amazing sisters and brothers • Those who have been waiting so long for my graduation vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Alhamdulillahi rabbil’alamiin. All praises be only to Allah SWT, the Almighty, the Merciful, and the Great Giver. It is impossible to finish this thesis without His helps, blessings, and loves. I would like to express my great gratitude to all lecturers in English Education Department, especially to my consultants: Ibu Ari Nurhayati, M. Hum and Ibu Niken Anggraeni, M.A. who have shared their valuable time, knowledge, and guidance with all their patience and wisdom during the process of writing this thesis. My deepest gratitude goes to my beloved Mom and Dad for the endless love and prayers and also for being patient enough to wait for me to finish my study; to my sisters (Mba Ela, Mimi, Uni, and Teteh) and brothers (Maz’in, Mamotank, Uki, and Mamibah) for every support; and to my lovely nieces and nephews for their cheerful smiles.