Panic Con. Stat. Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEMAND REDUCTION a Glossary of Terms

UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.00.XI.9 ISBN: 92-1-148129-5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was prepared by the: United Nations International Drug Control Programme (UNDCP), Vienna, Austria, in consultation with the Commonwealth of Health and Aged Care, Australia, and the informal international reference group. ii Contents Page Foreword . xi Demand reduction: A glossary of terms . 1 Abstinence . 1 Abuse . 1 Abuse liability . 2 Action research . 2 Addiction, addict . 2 Administration (method of) . 3 Adverse drug reaction . 4 Advice services . 4 Advocacy . 4 Agonist . 4 AIDS . 5 Al-Anon . 5 Alcohol . 5 Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) . 6 Alternatives to drug use . 6 Amfetamine . 6 Amotivational syndrome . 6 Amphetamine . 6 Amyl nitrate . 8 Analgesic . 8 iii Page Antagonist . 8 Anti-anxiety drug . 8 Antidepressant . 8 Backloading . 9 Bad trip . 9 Barbiturate . 9 Benzodiazepine . 10 Blood-borne virus . 10 Brief intervention . 11 Buprenorphine . 11 Caffeine . 12 Cannabis . 12 Chasing . 13 Cocaine . 13 Coca leaves . 14 Coca paste . 14 Cold turkey . 14 Community empowerment . 15 Co-morbidity . 15 Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Outline of Future Activities in Drug Abuse Control (CMO) . 15 Controlled substance . 15 Counselling and psychotherapy . 16 Court diversion . 16 Crash . 16 Cross-dependence . 17 Cross-tolerance . 17 Custody diversion . 17 Dance drug . 18 Decriminalization or depenalization . 18 Demand . 18 iv Page Demand reduction . 19 Dependence, dependence syndrome . 19 Dependence liability . 20 Depressant . 20 Designer drug . 20 Detoxification . 20 Diacetylmorphine/Diamorphine . 21 Diuretic . 21 Drug . 21 Drug abuse . 22 Drug abuse-related harm . 22 Drug abuse-related problem . 22 Drug policy . 23 Drug seeking . 23 Drug substitution . 23 Drug testing . 24 Drug use . -

Alcohol Responsibly and Ending Tobacco Use, Plus Caffeine - Dr

MHE-110 – Chapter Nine – Drinking Alcohol Responsibly and Ending Tobacco Use, plus Caffeine - Dr. Dave Shrock Chapter Nine Alcohol - an overview Alcohol and ending Tobacco Use 13th pp. 239-240; 12th pp. 232-223 • alcohol is the most widely used drug in the United (including caffeine) States • 86% of Americans consume alcohol 13th edition, pp. • 10% are heavy drinkers…who consume half of all the 241-269 alcohol produced 12th edition: • no other form of addiction or disability costs the US pp. 231-261 more than alcohol use/abuse annually Excessive alcohol use causes 88,000 deaths annually (chapter eight) twice as many as illicit drugs • lost work time, illness, insurance, accidents, medical costs take a toll on all of us…25% of all medical costs in the US are alcohol related Alcohol: The world’s most what is alcohol? dangerous drug? 13th, pp. 239-240; 12th pp. 232-233 The Lancet Medical Journal - 1 November, 2016 • alcohol is a byproduct of fermentation • In a recent article published in of vegetable or fruit pulp or ‘mash’ the British medical journal The this produces a concentration of Lancet, when considering the alcohol up to 14% drug’s damage to: • distillation is a further process by •one’s self capturing the vapors from heating • one’s family the mash, and mix this with water • the environment • proof is the measure of % of alcohol, which means the % • economic cost of alcohol is half of the ‘proof rating’ • Alcohol is the world’s most • some alcohol is 152 proof, or 71% alcohol most beers are damaging drug to individuals 8 proof, or 4% alcohol. -

Psychostimulants Tobacco and Nicotine

Psychostimulants Psychostimulants produce: • Increases in alertness. • Behavioral arousal. • Activation of sympathetic nervous system. • Sympathomimetic Effects Tobacco and Nicotine 1 Tobacco • Native Americans were the first to utilize tobacco. • Columbus discovered tobacco in the new world. • Tobacco use spread rapidly through Europe. Tobacco Preparations • Smoking Tobacco • Chewing Tobacco • Snuff Active ingredient is nicotine. • Named after Nicotiana. • Found only in tobacco. Behavioral / Physiological Effects of Nicotine • Pleasure/Euphoria • Sympathomimetic effects. • Increases in alertness. • Maybe overestimated? • Appetite Suppressant/Nausea • Muscle Tremor • Nesbitt’s Paradox 2 Pharmacokinetics Inhalation Absorption • Very rapid absorption. • One cigarette contains 1-5 mg nicotine. • A smoker utilizes ≈1 mg of this nicotine. • Dose control is important. • Low tar/nicotine cigarettes? Oral/Nasal Absorption • Nicotine is basic, so G.I. tract absorption is poor. • Cigarette smoke makes the saliva acidic. • Nicotine poorly absorbed in mouth. • Pipe and cigar smoke isn’t acidic. • Nicotine easily absorbed in mouth. • Nicotine from chewed tobacco and snuff absorbed through oral/nasal membranes. Nicotine easily crosses the blood brain barrier. Metabolism • 80-90% metabolized by the liver. • Remainder secreted in urine. • Half-life of ≈1 hour. 3 Pharmacodynamics - Nicotine is an agonist at nicotinic ACh receptors. • In the PNS, nicotine: • Causes adrenal medulla to release norepinephrine and epinephrine. • Sympathomimetic Effects • Activates receptors at the neuromuscular junction. • Muscle Tremor In the CNS, nicotine activates presynaptic axo-axonic receptors. A x o n 2 N T N T N T NT NT Axon 1 Dendrite NT Increases NT release from Axon 1. • Presynaptic Facilitation Many different NTs can be facilitated. • DA in the Nucleus Accumbens • Catecholamines in brainstem arousal centers. -

The Effects of Adenosine Antagonists on Distinct Aspects of Motivated Behavior: Interaction with Ethanol and Dopamine Depletion

Facultat de Ciències de la Salut Departament de Psicologia Bàsica, Clínica i Psicobiologia The effects of adenosine antagonists on distinct aspects of motivated behavior: interaction with ethanol and dopamine depletion. PhD Candidate Laura López Cruz Advisor Dr. Mercè Correa Sanz Co-advisor Dr. John D.Salamone Castelló, May 2016 Als meus pares i germà A Carlos AKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was funded by two competitive grants awarded to Mercè Correa and John D. Salamone: Chapters 1-4: The experiments in the first chapters were supported by Plan Nacional de Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Spain. Project: “Impacto de la dosis de cafeína en las bebidas energéticas sobre las conductas implicadas en el abuso y la adicción al alcohol: interacción de los sistemas de neuromodulación adenosinérgicos y dopaminérgicos”. (2010I024). Chapters 5 and 6: The last 2 chapters contain experiments financed by Fundació Bancaixa-Universitat Jaume I. Spain. Project: “Efecto del ejercicio físico y el consumo de xantinas sobre la realización del esfuerzo en las conductas motivadas: Modulación del sistema mesolímbico dopaminérgico y su regulación por adenosina”. (P1.1B2010-43). Laura López Cruz was awarded a 4-year predoctoral scholarship “Fornación de Profesorado Universitario-FPU” (AP2010-3793) from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. (2012/2016). TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................1 RESUMEN .....................................................................................................................3 -

Effect of Caffeine Consumption on the Risk for Neurological And

nutrients Review Effect of Caffeine Consumption on the Risk for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders: Sex Differences in Human Hye Jin Jee 1,2, Sang Goo Lee 1, Katrina Joy Bormate 1 and Yi-Sook Jung 1,2,* 1 College of Pharmacy, Ajou University, Suwon 16499, Korea; [email protected] (H.J.J.); [email protected] (S.G.L.); [email protected] (K.J.B.) 2 Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technology, Ajou University, Suwon 16499, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-3-1219-3444 Received: 26 August 2020; Accepted: 4 October 2020; Published: 9 October 2020 Abstract: Caffeine occurs naturally in various foods, such as coffee, tea, and cocoa, and it has been used safely as a mild stimulant for a long time. However, excessive caffeine consumption (1~1.5 g/day) can cause caffeine poisoning (caffeinism), which includes symptoms such as anxiety, agitation, insomnia, and gastrointestinal disorders. Recently, there has been increasing interest in the effect of caffeine consumption as a protective factor or risk factor for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Currently, the importance of personalized medicine is being emphasized, and research on sex/gender differences needs to be conducted. Our review focuses on the effect of caffeine consumption on several neurological and psychiatric disorders with respect to sex differences to provide a better understanding of caffeine use as a risk or protective factor for those disorders. The findings may help establish new strategies for developing sex-specific caffeine therapies. Keywords: caffeine; neurological and psychiatric disorders; sleep disorder; stroke; dementia; depression; sex differences 1. Introduction Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine), a type of methylxanthine series alkaloid [1], is commonly found in coffee, tea, and soft drinks, and also exists in cocoa, chocolate, and a number of dietary supplements [2]. -

Current Science of Addictions

Current Science of Addictions Darryl S. Inaba, PharmD. Clinical Manager, Genesis of Asante Health System, Central Point, Oregon Director of Education and Research, CNS Productions, Medford, Oregon Associate Clinical Professor, UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, CA Instructor, Special Consultant, University of Utah School on Alcohol and Other Drug Dependencies, Salt Lake City, UT Adjunct Professor, College of San Mateo, Alcohol and Other Drug Studies, San Mateo, CA HAFCI Fellow, Haight Ashbury Free Clinics, Inc., San Francisco, California PRESENTATION GOALS: Participation in this presentation will result in the following: • Increased awareness of rapidly growing science of Addictionology. • Clearer understanding of alcoholism and addicted populations. • Familiarity with basic neurocellular and neurochemical mechanisms of compulsive behaviors. • Consider the complexity of medication prescribing for the addictive population. • Better understanding of various evidenced-based approaches for chemical dependency treatment inclusive of the role of culturally consistent innovations PRESENTATION OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of the presentation, participants will be able to: • Cite at least 4 commonly held myths or misconceptions that hamper the understanding of and appropriate medical interactions with chemically dependent individuals. • Describe populations and prevalence of alcohol and other drug addictions in the US along with its impact on our economy and public health. • Name the 4 brain structures in the meso and neo cortex that are vital to the Reward Reinforcement Circuitry in chemical dependence. • List at least 3 classes of commonly prescribed psychoactive medications that can lead to cravings and relapse in recovering addicts. • Identify and list at least 5 neurotransmitters that are disrupted by drug abuse and addiction. 1 Current Science of Addiction I. -

Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs: Clinical Guidelines for Nurses and Midwives

Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs: Clinical Guidelines for Nurses and Midwives Version 3, 2012 Endorsed by the South Australian Alcohol and Drug Nursing and Midwifery Statewide Action Group This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. Commercial usage or sale is not permissible without negotiation with the authors. Electronic Index: This publication is available as a down-loadable PDF with fully searchable text. To access PDF copies go to: www.dassa.sa.gov.au www.health.adelaide.edu.au/nursing For further information contact: The University of Adelaide School of Nursing Phone (08) 8303 3595 Email: [email protected] This work may be cited as: de Crespigny, C & Talmet, J. 2012. (Eds). Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs: Clinical Guidelines for Nurses and Midwives. Version 3. The University of Adelaide School of Nursing, Drug and Alcohol Services, South Australia. Subject Keywords: Alcohol, Tobacco, Other Drugs, Drug and Alcohol, Substances, Clinical Guidelines, Nurses, Midwives. For Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact National Library of Australia: [email protected] ISBN 978-0-9803130-8-6 First printing Version 1 2003 Second printing Version 2 2003 Third printing Version 3 2012 © University of Adelaide and Drug & Alcohol Services, South Australia 2012 Foreword The use of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs (ATOD) is prevalent in our society. Nurses, midwives and other health care professionals are faced with a diverse group of consumers many of whom are affected either temporarily or in the longer term by ATOD related health challenges. -

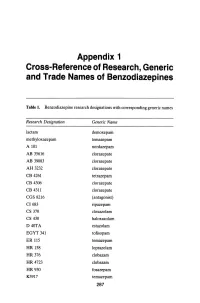

Appendix 1 Cross-Reference of Research, Generic and Trade Names of Benzodiazepines

Appendix 1 Cross-Reference of Research, Generic and Trade Names of Benzodiazepines Table 1. Benzodiazepine research designations with corresponding generic names Research Designation Generic Name lactam demoxepam methyloxazepam temazepam A 101 nordazepam AB 35616 clorazepate AB 39083 clorazepate AH 3232 clorazepate CB 4261 tetrazepam CB 4306 clorazepate CB 4311 clorazepate CGS 8216 (antagonist) CI683 ripazepam CS 370 cloxazolam CS 430 haloxazolam D40TA estazolam EGYT 341 tofisopam ER 115 temazepam HR 158 loprazolam HR376 clobazam HR 4723 clobazam HR930 fosazepam K3917 temazepam 287 THE BENZODIAZEPINES Research Designation Generic Name LA 111 diazepam LM 2717 clobazam ORF 8063 triflubazam Ro 4-5360 nitrazepam Ro 5-0690 chlordiazepoxide Ro 5-0883 desmethy1chlordiazepoxide Ro 5-2092 demoxepam Ro 5-2180 desmethyldiazepam Ro 5-2807 diazepam Ro 5-2925 desmethylmedazepam Ro 5-3059 nitrazepam Ro 5-3350 bromazepam Ro 5-3438 fludiazepam Ro 5-4023 clonazepam Ro 5-4200 flunitrazepam Ro 5-4556 medazepam Ro 5-5345 temazepam Ro 5-6789 oxazepam Ro 5-6901 flurazepam Ro 15-1788 (antagonist) Ro 21-3981 midazolam RU 31158 loprazolam S 1530 nimetazepam SAH 1123 isoquinazepam SAH 47603 temazepam SB 5833 camazepam SCH 12041 halazepam SCH 16134 quazepam U 28774 ketazolam U 31889 alprazolam U 33030 triazolam W4020 prazepam We 352 triflubazam 288 RESEARCH, GENERIC AND TRADE NAMES Research Designation Generic Name We 941 brotizolam Wy 2917 temazepam Wy 3467 diazepam Wy 3498 oxazepam Wy 3917 temazepam Wy 4036 lorazepam Wy 4082 lormetazepam Wy 4426 oxazepam Y 6047 -

Nicotine and Caffeine

7 Nicotine and Caffeine CHAPTER OUTLINE distribute • Nicotine: Key Psychoactive Ingredient in Tobacco • Discovery of Tobacco or • Tobacco Use and Pharmacokinetic Properties • Nicotine and Nervous System Functioning • Nicotine’s Potent Pharmacological Effects • Environmental, Genetic, and Receptor Differences Between Light and Heavy Tobacco Users • From Actions to Effects: Why People Smoke and How They Quit • Caffeine • Caffeine Absorption, Duration, and Interactionpost, With Other Psychoactive Drugs • Caffeine: Antagonist for Adenosine Receptors • Caffeine: Mild Psychostimulant Effects • Tolerance and Dependence During Sustained Caffeine Use • From Actions to Effects: Why People Consume Caffeinated Products • Chapter Summary copy, IS NICOTINE NOT ADDICTIVE? not On April 14, 1994, a House subcommittee met companies. In his opening remarks, the sub- to discuss the health concerns of tobacco use. committee chair reviewed the risks of tobacco Before the committee were seven corporate use: high mortality rate, cancer, heart dis- Do executive officers of large U.S.-based tobacco ease, and lung disease. Then Rep. Ron Wyden (Continued) 203 Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 204 Drugs and the Neuroscience of Behavior (Continued) (D–Oregon) asked the first question: “Yes or a clear, simple answer to Wyden’s answer: no, do you believe nicotine is not addictive?” Nicotine is not addictive. Did these CEOs have a defensible position? The executives’ responses made this hear- As presented later in this chapter, the CEOs’ ing famous. Down the line, every CEO made answers depend on how addiction is defined. n Chapter 6, we considered the most powerful psychostimulants: amphetamines, cathinones, and cocaine. -

STIMULANTS: Methylxanthines/Xanthines (P.1) (“Minor” Stimulants)

STIMULANTS: Methylxanthines/Xanthines (p.1) (“minor” stimulants) 1. Plant Sources of Xanthines (alkaloids) Coffee – Coffea Arabica (Ethiopia originally) Coffea robusta (African Congo originally) Tea – Camellia sinensis (China, India, Burma, Thailand, Laos & Vietnam) Chocolate – Theobroma cacao (Amazon & Orinoco rivers) So.Amer. Holly – Ilex guayusa (Amazon, Peru, Ecuador) Achuar Jivaro tribesmen (xanthines act to repel insects) 2. Specific Active Ingredients & Plant Sources Caffeine – found in coffee, tea, colas, & So.Amer. holly Theophylline – found in tea Theobromine – found in chocolate (along with phenylethylamine & caffeine) (caffeine > theophylline > theobromine) 3. Users of Xanthines Mean age of initial use: of coffee = 19 years; of tea = 22 years; of colas = 14 years; of choc? In USA > 85% of population consumes caffeine weekly > 98% of children/adolescents (5-18 yrs) consume weekly 210-238 mg caffeine/person/day (all sources)(mostly coffee) (Julien says 80-400 mg, = 3 to 5 5oz. “cups” of coffee/day) (vs. 444 mg caffeine/person/day in United Kingdom!)(mostly tea) coffee consumption was dropping & colas increasing – in early 1990’s (PS) In U.K. per capita consumption of chocolate is 16 lbs./year (vs. 12 lbs./year in USA) in U.K. around 20% of yearly chocolate is consumed at Xmas/NewYrs Worldwide 70mg caffeine/person/day (tea > coffee) 80% of adult population consumes caffeine daily Summary: Xanthine use is worldwide & daily! STIMULANTS: Methylxanthines (p.2) 4. General Positive Effects increased mental alertness, wakefulness increased -

Ÿþp R E F a C

9 Preface The present document represents a major effort. The work has been going on for almost three years, and has involved not only the committee members, but also the many members of the 12 subcommittees. The work in the committee and subcom- mittees has been open, so that all interim documents have been available to any- body expressing an interest. We have had a two-day meeting on headache classifi- cation in March 1987 open to everybody interested. At the end of the Third Interna- tional Headache Congress in Florence September 1987 we had a public meeting where the classification was presented and discussed. A final public meeting was held in San Diego, USA. February 20 and 21,1988 as a combined working session for the committee and the audience. Despite all effort, mistakes have inevitably been made. They will appear, when the classification is being used and will have to be corrected in future editions. It should also be pointed out that many parts of the document are based on the ex- perience of the experts of the committees in the absence of sufficient published evi- dence. It is expected however that the existence of the operational diagnostic criteria published in this book will generate increased nosographic and epidemio- logic research activity in the years to come. We ask all scientists who study headache to take an active part in the testing and further development of the classification. Please send opinions, arguments and reprints to the chairman of the classification committee. It is planned to publish the second edition of the classification in 1993. -

Neuropsychological Effects of Caffeine: Is Caffeine Addictive? Md

logy Uddin et al., J Psychol Psychother 2017, 7:2 ho & P yc s s y P c h DOI: 10.4172/2161-0487.1000295 f o o l t h a e n r r a u p o y J Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy ISSN: 2161-0487 ReviewResearch Article Article OMICSOpen International Access Neuropsychological Effects of Caffeine: Is Caffeine Addictive? Md. Sahab Uddin1#*, Mohammad Abu Sufian1#, Md. Farhad Hossain2, Md. Tanvir Kabir3, Md. Tanjir Islam1, Md. Mosiqur Rahman1 and Md. Rajdoula Rafe1 1Department of Pharmacy, Southeast University, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2Department of Physical Therapy, Graduate School of Inje University, Gimhae, Korea 3Department of Pharmacy, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh #Equal contributors Abstract Caffeine is the most widely used psychotropic drug in the world. Most of the caffeine consumed comes from coffee bean (i.e., a misnomer for the seed of Coffea plants), beverages (i.e., coffee, tea, soft drinks), in products containing cocoa or chocolate and in medications (i.e., analgesics, stimulants, weight-loss products, sports nutrition). The most prominent behavioral effects of caffeine take place over low to moderate doses are amplified alertness and attention. Moderate caffeine consumption leads very rarely to health risks. Higher doses of caffeine encourage negative effects such as anxiety, insomnia, restlessness and tachycardia. The habitual use of caffeine causes physical dependence that displays as caffeine withdrawal symptoms that harm normal functioning. Contrariwise, rarely high doses of caffeine can encourage psychotic and manic symptoms usually, sleep disturbances and anxiety. Even though caffeine does not engender life-threatening health difficulties frequently related to the utilization of drugs of addiction, for example amphetamine, cocaine and heroin, an incrementing number of clinical studies are exhibiting that some caffeine users become dependent on the drug and are unable to reduce consumption despite knowledge of recurrent health complications linked to constant use.