Article Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament Elections 2014

European Parliament Elections 2014 Updated 12 March 2014 Overview of Candidates in the United Kingdom Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS: VOTING METHOD IN THE UK ................................................................ 3 4.0 PRELIMINARY OVERVIEW OF CANDIDATES BY UK CONSTITUENCY ............................................ 3 5.0 ANNEX: LIST OF SITTING UK MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ................................ 16 6.0 ABOUT US ............................................................................................................................. 17 All images used in this briefing are © Barryob / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL © DeHavilland EU Ltd 2014. All rights reserved. 1 | 18 European Parliament Elections 2014 1.0 Introduction This briefing is part of DeHavilland EU’s Foresight Report series on the 2014 European elections and provides a preliminary overview of the candidates standing in the UK for election to the European Parliament in 2014. In the United Kingdom, the election for the country’s 73 Members of the European Parliament will be held on Thursday 22 May 2014. The elections come at a crucial junction for UK-EU relations, and are likely to have far-reaching consequences for the UK’s relationship with the rest of Europe: a surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) could lead to a Britain that is increasingly dis-engaged from the EU policy-making process. In parallel, the current UK Government is also conducting a review of the EU’s powers and Prime Minister David Cameron has repeatedly pushed for a ‘repatriation’ of powers from the European to the national level. These long-term political developments aside, the elections will also have more direct and tangible consequences. -

New ISER Evidence on Pay Gaps in the UK Workforce

INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH AUTUMN 2017 ISERNEWS World class socio-economic research and surveys In this issue Presenting at the 2 ESRC Festival of Social Science Methodology of 3Longitudinal Surveys Conference 2018 The EU commitment 4 to EUROMOD New flash estimates 5 of poverty levels across the EU New research on the The research on gender-based pay found the pay gap closing for full-time employment 6 cost of unpaid internship Identifying the least New ISER evidence on pay 7 well off in society Poverty and gaps in the UK workforce 8 wellbeing research: what makes children Equalities and Human Rights Commission publish new unhappy? findings and strategy in three separate reports The Equalities and Human Rights Commission and 6.9 per cent respectively. Pay gaps for ethnic (EHRC) has published new ISER research by Dr minority men were found to be much higher than Malcolm Brynin and Dr Simonetta Longhi on those for ethnic minority women. pay gaps in the UK workforce. Gender This study found the pay gap closing. There are three separate reports on disability In 1993 women earned 73 per cent of the pay gaps, ethnicity pay gaps and gender pay average male wage. By 2014 women earned gaps which are used as evidence for the EHRC’s just over 90 per cent. The gender wage gap for new strategy to tackle pay gaps. graduates declined in relative terms more than Ethnicity This study finds pay gaps are much for others. Part-time employment works in the larger for ethnic minority men born abroad than opposite direction and now part-time working for those born in the UK. -

Icm Research Job No (1-6) 960416

ICM RESEARCH JOB NO (1-6) KNIGHTON HOUSE 56 MORTIMER STREET SERIAL NO (7-10) LONDON W1N 7DG TEL: 0171-436-3114 CARD NO (11) 1 2004 LONDON ELECTIONS QUESTIONNAIRE INTRODUCTION: Good morning/afternoon. I am ⇒ IF NO 2ND CHOICE SAY: from ICM, the independent opinion research Q7 So can I confirm, you only marked one company. We are conducting a survey in this area choice in the London Assembly election? today and I would be grateful if you could help by (14) answering a few questions … Yes 1 No 2 ⇒ CHECK QUOTAS AND CONTINUE IF ON Don’t know 3 QUOTA Q1 First of all, in the recent election for the ***TAKE BACK THE BALLOT PAPERS*** new London Mayor and Assembly many people were not able to go and vote. Can you tell me, did ♦ SHOW CARD Q8 you manage to go to the polling station and cast Q8 When you were voting in the elections for your vote? the London Assembly and London Mayor, what (12) was most important to you? Of the following Yes 1 possible answers, can you let me know which were No 2 the two most important as far as you were Don’t know 3 concerned (15) ⇒ IF NO/DON’T KNOW, GO TO Q9 Q2 Here is a version of the ballot paper like the These elections were a chance to let one used for the MAYOR ELECTION. the national government know what 1 (INTERVIEWER: HAND TO RESPONDENT). Could you think about national issues you please mark with an X who you voted for as I felt it was my duty to vote 2 your FIRST choice as London Mayor? MAKE SURE Choosing the best people to run 3 RESPONDENT MARKS BALLOT PAPER IN London CORRECT COLUMN I wanted to support a particular party 4 I wanted to let the government know Q3 And could you mark with an X who you my view on the Iraq war 5 voted for as your SECOND choice? ? MAKE SURE RESPONDENT MARKS BALLOT PAPER IN ⇒ VOTERS SKIP TO Q16 CORRECT COLUMN Q9 Here is a version of the ballot paper like the ND one used for the MAYOR ELECTION. -

Conservative Party

Royaume-Uni 73 élus Parti pour Démocrates libéraux Une indépendance de Parti conservateur ECR Parti travailliste PSE l’indépendance du Les Verts PVE ALDE l'Europe NI Royaume-Uni MELD 1. Vicky Ford MEP 1. Richard Howitt MEP 1. Andrew Duff MEP 1. Patrick O’Flynn 1. Paul Wiffen 1. Rupert Read 2. Geoffrey Van Orden 2. Alex Mayer 2. Josephine Hayes 2. Stuart Agnew MEP 2. Karl Davies 2. Mark Ereira-Guyer MEP 3. Sandy Martin 3. Belinda Brooks-Gordon 3. Tim Aker 3. Raymond Spalding 3. Jill Mills 3. David Campbell 4. Bhavna Joshi 4. Stephen Robinson 4. Michael Heaver 4. Edmond Rosenthal 4. Ash Haynes East of England Bannerman MEP 5. Paul Bishop 5. Michael Green 5. Andrew Smith 5. Rupert Smith 5. Marc Scheimann 4. John Flack 6. Naseem Ayub 6. Linda Jack 6. Mick McGough 6. Dennis Wiffen 6. Robert Lindsay 5. Tom Hunt 7. Chris Ostrowski 7. Hugh Annand 7. Andy Monk 7. Betty Wiffen 7. Fiona Radic 6. Margaret Simons 7. Jonathan Collett 1. Ashley Fox MEP 1. Clare Moody 1. Sir Graham Watson 1. William Dartmouth 1. David Smith 1. Molly Scott Cato 2. Julie Girling MEP 2. Glyn Ford MEP MEP 2. Helen Webster 2. Emily McIvor 3. James Cracknell 3. Ann Reeder 2. Kay Barnard 2. Julia Reid 3. Mike Camp 3. Ricky Knight 4. Georgina Butler 4. Hadleigh Roberts 3. Brian Mathew 3. Gawain Towler 4. Andrew Edwards 4. Audaye Elesady South West 5. Sophia Swire 5. Jude Robinson 4. Andrew Wigley 4. Tony McIntyre 5. Phil Dunn 5. -

First Agenda Autumn Conference 2020

First Agenda Autumn Conference 2020 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2 Section A .................................................................................................................................... 5 A1 Amendments to Standing Orders for the Conduct of Conference to enable an online and telephone Extraordinary Conference to be held in Autumn 2020 ................................. 5 A2 Enabling Motion for an Extraordinary Autumn Conference 2020 to be held online ....... 7 Section B .................................................................................................................................... 8 B1 Food and Agriculture Voting Paper .................................................................................. 8 Section C................................................................................................................................... 15 C1 Adopt the Principle of Rationing to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions Arising from Travel, Amending the Climate Emergency and the Transport Chapters of PSS .................. 15 C2 The 2019 General Election Manifesto and Climate Change Mitigation ......................... 17 C3 Animal Rights: Fireworks; limit use and quiet ................................................................ 19 C4 Updating the philosophical basis to reflect doughnut economics ................................. 20 C5 Car and vans to go zero carbon by -

One World. One Chance. One World

ONE WORLD. ONE CHANCE. ONE WORLD. ONE CHANCE. Green Party Green Party Jean Lambert A proven track record EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT When you voted Green, you elected Jean ELECTIONS 4TH June Lambert as London’s Green MEP. She has voted to: • make sure you are treated equally, whatever your age, race, gender, disability, sexual orientation or belief • protect your rights at work • stop cruelty to animals. Jean Lambert, Green MEP Jean has worked to: • protect your environment and London’s Green Candidates your health Jean Lambert Miranda Dunn • give you a voice when decisions Ute Michel Shasha Khan Shahrar Ali John Hunt are taken. Joseph Healy Caroline Allen Your vote really counts Just one in ten voters backing the Green For information about this campaign, or to donate to it: Party on 4th June should ensure Jean phone: 0207 99 80 492 Lambert is re-elected to the European text: GREEN to 81707 Parliament. Under the proportional Calls will be charged at your standard rate voting system every vote counts. Vote email: [email protected] Green and help get Jean re-elected. www.london.greenparty.org.uk. VOTE GREEN. RE-ELECT JEAN laMBERT. VOTE GREEN. RE-ELECT JEAN LAMBERT. Promoted by Martin Bleach on behalf of London Green Party, both at 1a Waterlow Road, London N19 5NJ. Printed by York Mailing Ltd York YO41 4AU on 100% recycled paper. ELECTION COMMUNICATION LONDON REGION ONE WORLD. ONE CHANCE. Green Party We want a future where we live The European Union will be part of our changing future. within our means: How it changes will depend on your vote. -

Statement:Defend EU Migrants' Rights

STAND UP TO RACISM Statement: Defend EU migrants’ rights In his first statement as prime minister, Islamophobic and racist comments Mark Serwotka PCS general secretary Boris Johnson gave ‘unequivocally by Johnson and his support for openly Rabbi Lee Wax our guarantee to the 3.2 million antisemitic leaders such as Viktor Lord Alf Dubs EU nationals now living and Orbán, suggest that the likelihood of Sabby Dhalu & Weyman Bennett working among us...that, under racist attacks on migrant rights is high, Stand Up To Racism co convenors this Government, they will have the as does Johnson’s commitment to a Kate Osamor MP absolute certainty for the right to live points-based immigration system. Catherine West MP and remain.” Lloyd Russel-Moyle MP Legislation should be passed to In less than a day, his spokesperson Lord Peter Hain guarantee the legal status of all rushed to clarify that this did not mean Julie Ward MEP new legislation would be proposed. EU migrants who live here.At a Claude Moraes MEP Instead Johnson would maintain the minimum the government must: Mike Hedges Welsh Assembly Member EU Settlement Scheme. ● Scrap the 5 year cap – every EU Green Party home affairs As campaigners have pointed out, Shahrar Ali national resident in the UK should spokesperson the current scheme implies that preserve all their current rights. migrants who fail to apply will lose Unmesh Desai Greater London ● The original deadline advertised by Assembly their legal status and residency rights. the Home Office to apply for settled Rokhsana Fiaz Newham Mayor Figures suggest at least 2 million EU status be re-established. -

Article Template

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the Conway Hall Ethical Society Vol. 120 No. 11 £1.50 November 2015 Moncure Daniel Conway A VERY UNUSUAL VIRGINIAN see page 16 UPDATE ON ‘NO PLATFORM’ IN STUDENT MEETINGS We have some better news since the October Ethical Record (page 1) reported the banning of secularist Maryam Namazie from speaking at a Warwick students atheist society. After earnest conversations between Humanist and Secular organisations and the National Union of Students, that particular ban was lifted. Nevertheless, fear of the expression of forthright opinions and strong views on contemporary issues from being aired still lurks on campus. We can therefore expect more examples coming to light of similar, somewhat cowardly, behaviour. Universities and their student societies are supposed to be places where all theories and ideologies may be peacefully propounded and debated. {Ed.} GREENER THAN GREEN Jasper Tomlinson 3 ROSA PARKS, GANDHI AND ACTIVE NONVIOLENCE 1 Shahrar Ali 6 VIEwPOINTS C. Seymour, C. Purnell, P. Wilkinson, D. Ruskin 9 A LETTER FROM CANADA Ellen L. Ramsay 11 LONDON THINKS - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: ALL TOO HUMAN? Caroline Christie 12 MONCURE DANIEL CONwAY: A VERY UNUSUAL VIRGINIAN Nigel Sinnott 16 KILLING ATHEISTS IN BANGLADESH Bob Churchill 22 FORTHCOMING EVENTS 24 CONWAY HALL ETHICAL SOCIETY Conway Hall Humanist Centre 25 Red Lion Square, London WC1R 4RL. www.conwayhall.org.uk Chairman: Liz Lutgendorff; Treasurer: Carl Harrison; Editor: Norman Bacrac Please email texts and viewpoints for the Editor to: [email protected] Staff Chief Executive Officer: Jim Walsh Tel: 020 7061 6745 [email protected] Administrator: Martha Lee Tel: 020 7061 6741 [email protected] Finance Officer: Linda Lamnica Tel: 020 7061 6740 [email protected] Library/Learning: S. -

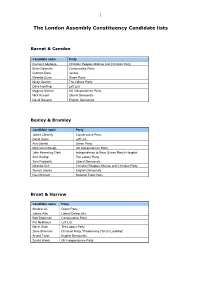

The London Assembly Constituency Candidate Lists

1 The London Assembly Constituency Candidate lists Barnet & Camden Candidate name Party Clement Adebayo Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Brian Coleman Conservative Party Graham Dare Veritas Miranda Dunn Green Party Nicky Gavron The Labour Party Dave Hoefling Left List Magnus Nielsen UK Independence Party Nick Russell Liberal Democrats David Stevens English Democrats Bexley & Bromley Candidate name Party James Cleverly Conservative Party David Davis Left List Ann Garrett Green Party Mick Greenhough UK Independence Party John Hemming-Clark Independence to Save Queen Mary's Hospital Alex Heslop The Labour Party Tom Papworth Liberal Democrats Miranda Suit Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Steven Uncles English Democrats Paul Winnett National Front Party Brent & Harrow Candidate name Party Shahrar Ali Green Party James Allie Liberal Democrats Bob Blackman Conservative Party Pat McManus Left List Navin Shah The Labour Party Zena Sherman Christian Party "Proclaiming Christ's Lordship" Arvind Tailor English Democrats Sunita Webb UK Independence Party 2 The London Assembly Constituency Candidate lists City & East (Newham, Barking & Dagenham, Tower Hamlets, City of London) Candidate name Party Hanif Abdulmuhit Respect (George Galloway) Robert Bailey British National Party John Biggs The Labour Party Candidate Philip Briscoe Conservative Party Thomas Conquest Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Julie Crawford Independent Heather Finlay Green Party Michael Gavan Left List John Griffiths English Democrats Rajonuddin -

Open House? Reflections on the Possibility and Practice of Mps Job-Sharing

Open House? Reflections on the possibility and practice of MPs job-sharing September 2017 This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council – Grant ES/M500410/1 CONTENTS Forewords 4 Acknowledgements 5 1. Introduction 8 Rosie Campbell and Sarah Childs 2. What is Job-sharing and How Has It Developed as a Practice? 11 Pam Walton 3. The High Court Case 17 Rosa Curling 4. Seeking Job-Share Candidature for the UK Parliament 21 Sarah Cope and Clare Phipps 5. Job-sharing and Parliamentary Representation – A Revolutionary Innovation? 25 Some notes towards a legal analysis bob watt 6. Changing the Ways Things Are Done – The Case for Disabled People Job-sharing 30 in Politics Emily Brothers 7. The Case For and Against MP Job-sharing 33 Rosie Campbell and Sarah Childs 8. We Can’t Change Because We Never Have. Really? 39 Sam Smethers FOREWORDS “The time for job-sharing MPs has arrived. The practice has been in place in the public and private sector for decades, where it has worked well in senior positions, and Parliament ought to catch up. This simple step would, I am confident, make Parliament much more representative. It would enable a far wider range of voices, including more women and disabled people, to be present in our debates. That has got to be good news for the quality of our democracy.” Tom Brake, Liberal Democrat MP for Carshalton and Wallington and Shadow First Secretary of State “Job-sharing has so much potential to open up our politics and make it more plural and more progressive. -

Matt Hodgkinson

Matt Hodgkinson Address Hindawi Limited, Third Floor, Adam House, 1 Fitzroy Square, London, W1T 5HF E-mail [email protected] Phone +44 (0)20 3146 9309 Websites orcid.org/0000-0003-1973-1244; about.me/matt_hodgkinson Work 06/2016–present Hindawi, London 10/2020-present Head of Editorial Policy and Ethics Review of editorial policies, proposing initiatives and policies to ensure robust peer review, and resolving complex editorial and ethical issues 06/2016-09/2020 Head of Research Integrity Management of publication ethics policies and processes, including retractions, corrections, and contacting institutions, and managing the Research Integrity team, including the Research Integrity Manager and overseeing the work of a vendor staff team 02/2010–06/2016 Public Library of Science (PLOS), Cambridge 10/2014–2016 Senior Editor, PLOS ONE Management and training of Associate Editors, management of Section Editors project and publication ethics issues 10/2010–09/2014 Associate Editor, PLOS ONE Submission and decision scanning, oversight of clinical trials, statistical reviewers, and article commenting, advising on clinical research and ethics, supporting academic editors with peer review and decision making, article-level metrics team 02/2010–09/2010 Freelancing, PLOS ONE Submission scanning, suggesting academic editors and peer reviewers, assessing potential academic editors 06/2010 Diffusion, London Freelancing, scientific report on genetics for a PR pitch 10/2003–04/2010 BioMed Central (BMC), London 04/2009–04/2010 Freelancing, peer -

General Election Candidate Details

General Election Candidate Details Barking Margaret Hodge, Lab, [email protected] @margarethodge (the sitting MP) Tamkeen Akhterrasul Shaikh, Con, [email protected] @tamkeenshaikh Ann Haigh, Lib Dem, [email protected] Shannon Butterfield, Green, [email protected] Karen Batley, Brexit Party, [email protected] @BatleyKaren Bermondsey and Old Southwark Neil Coyle, Labour, [email protected] @coyleneil Andrew Baker, Con, [email protected] @agsbaker235 Humaira Ali, Liberal Democrat, [email protected] @cllrhumaira Alex Matthews, Brexit Party, [email protected] @apmmatthews Bethnal Green & Bow Rushanara Ali, Lab, [email protected] @rushanaraali (the sitting MP) Nick Stovold, Con, [email protected] @nick_stovold Josh Babarinde, Lib Dem, [email protected] Shahrar Ali, Green, [email protected] @ShahrarAli David Axe, Brexit Party, [email protected] @DavidAxePPC Camberwell & Peckham Harriet Harman, Lab, [email protected] @HarrietHarman (the sitting MP) Peter Quentin, Con, [email protected] Julia Ogiehor, Lib Dem, [email protected] @juliaogiehor Claire Sheppard, Green, [email protected] @ShinyShep Chingford & Woodford Green Iain Duncan-Smith, Con, [email protected] (the sitting MP) Lab, Faiza Shaeen, [email protected] @faizashaheen Geoffrey Seef, Lib Dem, [email protected] @GSeeff Dagenham & Rainham Jon Cruddas, Lab, [email protected]