Understanding the Educational Needs of Rural Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methodist Church of Southern Africa

METHODIST CHURCH OF SOUTHERN AFRICA NATAL COASTAL DISTRICT MS 21 003 This is a Finding Aid for an amalgamation of material from the Natal Coastal District and consists primarily of content deposited in Cory Library by Rev. John Borman and Bishop Mike Vorster of the Natal Coastal District. It does not include previously catalogued material. Items have been arranged according to 8 main categories, and the contents of each folder briefly described. Folders are numbered consecutively within each category, so that one will find an A3, B3, C3 etc. The eight categories are: A. Zululand Mission (51 folders, plus photographs, c. 1900 – 2007) B. Indian Mission (6 folders, c. 1914 -1985) C. District Mission Department (26 folders, c. 1979 – 2006) D. Christian Education and Youth Department (18 folders, c. 1984 -2008) E. Women’s Auxiliary, Manyano, Biblewomen, Deacons, Evangelists and Local Preachers (28 folders, c. 1917 – 2008) F. Circuits, Societies and the District Executive (91 folders, c. 1854 – 2008) G. Methodist Connexional Office (Durban) (15 folders, c. 1974 – 2008) H. Miscellaneous (25 folders, c. 1981 – 2008) Natal Coastal District includes the metropolitan circuits of Durban, as well as the smaller urban and rural circuits northwards to the Mozambican border. Early mission work in Natal and the then Crown Colony of Zululand led to the formation of the Zululand Mission, after Rev. Thomas Major reported on the need for support at Melmoth, Mahlabatini, Nongoma, Ubombo, Ingwavuma and Maputaland. Early work was performed by local evangelists under one Superintendent. Threlfall Mission was established in Maputaland, but later re-sited to nearby Manguzi, where a Methodist Mission Hospital was established in 1942. -

In Maputaland

University of Pretoria – Morley R C (2006) Chapter 2 Study Area Introduction Maputaland is located at the southernmost end of the Mozambique Coastal Plain. This plain extends from Somalia in the north to northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, in the south (Watkeys, Mason & Goodman 1993). It encapsulates an area of about 26,734 km2 defined as the Maputaland Centre of Endemism (see van Wyk 1994). This centre is bordered by the Inkomati-Limpopo River in the north, the Indian Ocean in the east, the Lebombo Mountains in the west and the St. Lucia estuary to the south. Biogeographically the northern boundary of the centre is not as clearly defined as the other borders (van Wyk 1994). Earlier authors (e.g. Moll 1978; Bruton & Cooper 1980) considered Maputaland as an area of 5,700 km2 in north-eastern KwaZulu- Natal. These authors clearly did not always consider areas beyond South Africa in their descriptions. There has been some contention over the name Maputaland, formerly known as Tongaland in South Africa (Bruton 1980). Nevertheless this now seems largely settled and the name Maputaland is taken to be politically acceptable (van Wyk 1994) and is generally accepted on both sides of the South Africa/Mozambique border. Maputaland is the northern part of the Maputaland-Pondoland Region, a more arbitrarily defined area of about 200 000 km2 of coastal belt between the Olifants- Limpopo River in the north (24oS), to the Great Kei River (33oS) in the south, bounded to the west by the Great Escarpment and to the east by the Indian Ocean (van Wyk 1994). -

Perceptions of Educators Towards Teenage Pregnancy in Selected Schools in Umkhanyakude District: Implications for Action

COLLEGE OF LAW AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES Perceptions of educators towards teenage pregnancy in selected schools in UMkhanyakude District: Implications for action SUBMITTED BY THANDIWE SYLVIA NDLOVU 213571964 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Public Administration School of Management, Information Technology and Governance Supervisor: Dr BR Qwabe 2019 DECLARATION I, Thandiwe Sylvia Ndlovu, declare that: i. This dissertation except where otherwise indicated is my original research. ii. This dissertation has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. iii. This dissertation does not contain other person’s data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specially acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. iv. This dissertation does not contain other person’s writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted: Their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been properly reference; Where their exact words have been used, their writing has been quoted and referenced. v. This dissertation does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the dissertation and in the references sections. Signature: _____________________ Date: 25/08/2020 i DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my late father James Ndlovu. I strongly wish that he was still alive to celebrate my achievement. I thank him for being a loving and supportive father. May his soul, rest in peace. In your absence, I will leave this in the hands of my only daughter, Ziyanda. -

Training Manual 20091115 Sodwana

‘About iSimangaliso’ Topics relevant to Sodwana Bay and Ozabeni November 2009 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................1 Plant and animal names in “About iSimangaliso” .........................................................................3 Section 1: Introduction to the iSimangaliso Wetland Park ...........................................................5 ‘Poverty amidst Plenty’: Socio-Economic Profile of the Umkhanyakude District Municipality .5 The first World Heritage Site in South Africa ..................................................................................9 iSimangaliso’s "sense of place" ....................................................................................................13 A new model for Protected Area development: Benefits beyond Boundaries ..........................16 Malaria ..............................................................................................................................................23 Section 2: Topics .............................................................................................................................28 Bats of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park .........................................................................................28 The climate of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park .............................................................................32 The coast and shoreline of iSimangaliso ......................................................................................35 -

APOSTOLIC VICARIATE of INGWVUMA, SOUTH AFRICA Description the Apostolic Vicariate of Ingwavuma Is in the Northeastern Part of the Republic of South Africa

APOSTOLIC VICARIATE OF INGWVUMA, SOUTH AFRICA Description The Apostolic Vicariate of Ingwavuma is in the northeastern part of the Republic of South Africa. It includes the districts of Ingwavuma, Ubombo and Hlabisa. The Holy See entrusted this territory to the Servite Order in 1938 and the Tuscan Province accepted the mandate to implant the Church in this area (implantatio ecclesiae). Bishop Costantino Barneschi, Vicar Apostolic of Bremersdorp (now Manzini) asked the American Province to send friars for the new mission. Fra Edwin Roy Kinch (1918-2003) arrived in Swaziland in 1947. Other friars came from the United States and the Apostolic Prefecture of Ingwavuma was born. On November 19, 1990 the territory became an Apostolic Vicariate. After the Second World War the missionary territory was assumed directly by the friars of the North American provinces. By a decree of the 1968 General Chapter the then existing communities were established as the Provincial Vicariate of Zululand, a dependency of the US Eastern Province. At present there are 10 Servite friars who are members of the Zululand Delegation OSM. Servites The friars of the Zululand delegation work in five communities: Hlabisa, Ingwavuma, KwaNgwanase, Mtubtuba and Ubombo; there are 9 solemn professed (2 local, 2 Canadian and 5 from the US). General Information Area: 12,369 sq km; population: 609,180; Catholics: 23,054; other denominations: Lutherans, Anglicans, Methodists: 150,000; African Churches 60,000; non-Christian: 300,000; parishes: 5; missionary stations: 68; 8 Servite priests and one local priest: Father Wilbert Mkhawanazi. Lay Missionaries: 3; part-time catechists: 160; full-time catechists: 9. -

Umhlabuyalingana Municipality Housing Sector Plan

[MAY 2009] UMHLABUYALINGANA MUNICIPALITY HOUSING SECTOR PLAN MR E. MANQELE UMHLABUYALINGANA MUNICIPALITY PREPARED BY: TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1 INTRODUCTION: ............................................................................................................. 1 2 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................... 1 2.1 approach ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.2 methodology ............................................................................................................................ 2 2.3 structure of the report .............................................................................................................. 3 3 POLICY REVIEW ............................................................................................................. 4 3.1 THE CONSTITUTION .................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 national housing code ............................................................................................................... 4 3.3 comprehensive plan for the development of human settlements ............................................. 5 3.4 expanded public works program ............................................................................................... 6 3.5 Housing Programmes and Subsidies ........................................................................................ -

Export This Category As A

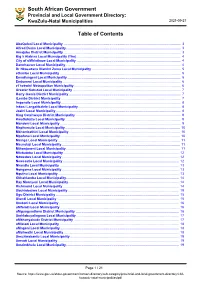

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Kosi Forest Lodge Directions

Updated: April 2011 Directions to Kosi Forest Lodge Recommended route from Johannesburg : (8 hours) Head to Piet Retief on the N2, pass through Pongola and proceed south towards Hluhluwe (approximately 113km from Pongola). Turn left into the town of Hluhluwe (approx. 4kms) and follow the instructions below " Recommended route from Durban ". *** Alternate Route from Johannesburg : Head to Piet Retief and Pongola on the N2 and proceed south towards Mkuze. Approximately 45km from Pongola and 10km before Mkuze turn left towards Jozini. On leaving Jozini take a left turn towards the “Coastal Forest Reserve and KwaNgwanase” (signposted), ensuring that you are proceeding over the Pongola dam wall. After 45km at a T-junction turn right towards “KwaNgwanase”. Proceed for another 47 km past Tembe Elephant Park towards the town of Manguzi (KwaNgwanase). Please note that this route often has cattle wandering across it, some of the signs have fallen down and so caution and slower driving speeds are necessary. Also particularly around the area of Tembe Elephant Park, the road has quite a few large potholes which have caused damage to some cars. Although this route may appear shorter in distance, it takes almost as much time as the Hluhluwe Recommended Route above, but without all the hazards! From Durban City: (5 hours) From Durban, proceed on the N2 North out of Durban bypassing Richards Bay, Empangeni and Mtubatuba and head towards the town of Hluhluwe. Turn off the N2 towards Hluhluwe, proceeding through the town until you reach the last traffic circle. Turn left towards Mbazwane/Sodwana Bay and proceed for 0.7 km and turn right again towards Sodwana Bay/Mbazwane. -

Kosi Bay Nature Reserve, South Africa

KOSI BAY NATURE RESERVE SOUTH AFRICA Information sheet for the site designated to the List of Wetlands of International Importance in terms of the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat South African Wetlands Conservation Programme Document No 24/21/3/3/3/11 (1991) Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Private Bag X447 PRETORIA 0001 South Africa ------------------------------------------------------------------------ KOSI BAY NATURE RESERVE: RAMSAR DATA 1. COUNTRY South Africa 2. DATE OF COMPILATION Originally completed: Nov/Dec 1988 Updated: Oct 1995 3. REFERENCE NUMBER 1ZA011 4. COMPILER Originally compiled by: Updated by: Dr Robert Kyle a) Dr Robert Kyle Fisheries Research Officer b) M C Ward PO Box 43 a) PO Box 43 KwaNgwanase KwaNgwanase 3973 3973 South Africa b) Private Bag X314 Tel (035) 5721011 Mbazwana Fax (035) 5721011 3974 5. NAME OF WETLAND KOSI BAY NATURE RESERVE 6. DATE OF RAMSAR DESIGNATION 28 June 1991 7. GEOGRAPHICAL CO-ORDINATES 26 52' S - 27 10' S, 32 42' E - 32 54' E Maps Number 1: 50 000 2632 DD and 2732 BB. 8. GENERAL LOCATION The system is orientated on an east north-east to south south-west axis. Bounded by Mozambique in the north and the Indian Ocean in east. The western border encapsulates the lakes of the Kosi System from a point on the Mozambique border ± 4 km from the Ocean. The border goes round much of the extant swamp forest around the system and in the south includes much of the catchment. In the north west the reserve boundary includes a narrow strip of land around the margins of the lakes. -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

952 23-5 Kzntransg3 Layout 1

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE RKEPUBLICWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIEREPUBLIIEK OF VAN SOUTHISIFUNDAZWEAFRICA SAKWAZULUSUID-NATALI-AFRIKA Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY—BUITENGEWONE KOERANT—IGAZETHI EYISIPESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG, 23 MAY 2013 Vol. 7 23 MEI 2013 No. 952 23 KUNHLABA 2013 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 302077—A 952—1 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 23 May 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. Page No. ADVERTISEMENT Road Carrier Permits, Pietermaritzburg........................................................................................................................ -

Important Information

IMPORTANT INFORMATION 1. All rates quoted are inclusive of Community Levy and Emergency Rescue Levy. Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife is a non vat vendor. Tariffs are valid from 1 November 2019 to 31 October 2020 and are subject to alteration without prior notice. 2. High season dates are applicable over public holidays, school holidays, long weekends, events and high occupancy periods. 3. Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park: Conservation Fee: Overnight Visitors: A daily Conservation Levy of R240 per adult and R120 per child under 12 years will be charged. South African and Southern African Development Countries (SADC) residents who provide proof of identity may apply for a discount on this fee, (R120 per person per day). Day Visitors: Pay the Conservation Fee for Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park. 4. The SA Conservation Fee at Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park is not applicable to tour operators and travel agents. Other Parks: Overnight Visitors: are not required to pay the Conservation Fee except for Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park and parks that fall under the iSimangaliso Wetland Park. Day Visitors: Are required to pay a Conservation Fee. 5. South African residents 60 years and over and bona-fide students are granted a discount of 20% on accommodation tariffs during low season. These discounts exclude high season, events, wilderness trails, overnight hiking, bush camps and bush lodges. SA residents qualify for the above discount on presentation of identification and proof of age for pensioners, or a valid student card for students, failing which full rates will be charged. 6. Refunds on or after the arrival date will be processed by the relevant Regional Office on recommendation from the camp.