The Projectionist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Vera Sidhwa - Poems

Poetry Series Vera Sidhwa - poems - Publication Date: 2016 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Vera Sidhwa() www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Bear Oh teddy, I cuddle you, I look for the softness in you. My cuddling makes you soft, On my sofa cushion. I sit with you on my lap. Oh bear, I meet you in the forest. I see all your huge fur, And large, sharp teeth, In your big mouth. And I run the other way. Vera Sidhwa www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 A Bird A Bird It was in my brain. It was in my veins. It just took off and then, Flew it's own way in and out. The trees rocked in the wind. All nature seemed in, A fury and crazy. The bird flew away. This was a real bird you see. It was in and out of me. I looked at in glee. It was the bird of perfection. I knew it would bring news to me. For this I could really see, That all ideas have wings of their own. And this idea did too. Vera Sidhwa www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 A Chiming Bell A Chiming Bell A chiming bell resounded through, The daisies and flowers of this field. A chime heard by the flowers, Was their ever wanting need. You see, their field was silent, And the flowers needed a sound. The chiming bell knew this, So it chimed about and around. Through the loud fields now, The flowers began to listen. -

KILLING CHARLIE KAUFMAN Written by Wrick

KILLING CHARLIE KAUFMAN Written by Wrick Cunningham First Draft March 5, 2002 FADE IN: A BIG YELLOW BALLOON Fills the frame, shiny and perfect. As we PULL BACK, it’s: EXT. SANTA MONICA PIER - DAY The balloon is handed to a LITTLE GIRL by a VENDOR. The girl smiles at her MOTHER, joyous. A SECOND GIRL walks by, holding her MOTHER’S hand. The second girl scowls. SECOND LITTLE GIRL I want that pretty balloon, Mommy! SECOND GIRL’S MOTHER That’s hers, dear. You can get your own. SECOND LITTLE GIRL I don’t want another balloon! I want that one! SECOND GIRL’S MOTHER I’m sorry, sweetie, but.... The second little girl breaks free from her mother’s hand. SECOND LITTLE GIRL Give me that balloon! The second girl grabs the string above the shocked first girl’s clutching hand. The first mother looks down, daunted. FIRST LITTLE GIRL It’s my balloon! They struggle -- the balloon slips from their hands and rises. FIRST LITTLE GIRL (CONT'D) Oh, Mommy! The four females watch the yellow balloon float away. SECOND LITTLE GIRL Look what you did! FIRST LITTLE GIRL You can have the stupid old balloon now! The second little girl smiles big. SECOND LITTLE GIRL I can? Oh, thank you! See my yellow balloon, Mommy? Aren’t I so very lucky? The second girl’s mother gazes down at her daughter, bewildered. 2. THE YELLOW BALLOON Floats high above the ocean. As WIND BLOWS: DISSOLVE TO: “FADE IN:” ON A COMPUTER MONITOR SCREEN PULLING BACK, the screen is empty.. -

Xiami Music Genre 文档

xiami music genre douban 2021 年 02 月 14 日 Contents: 1 目录 3 2 23 3 流行 Pop 25 3.1 1. 国语流行 Mandarin Pop ........................................ 26 3.2 2. 粤语流行 Cantopop .......................................... 26 3.3 3. 欧美流行 Western Pop ........................................ 26 3.4 4. 电音流行 Electropop ......................................... 27 3.5 5. 日本流行 J-Pop ............................................ 27 3.6 6. 韩国流行 K-Pop ............................................ 27 3.7 7. 梦幻流行 Dream Pop ......................................... 28 3.8 8. 流行舞曲 Dance-Pop ......................................... 29 3.9 9. 成人时代 Adult Contemporary .................................... 29 3.10 10. 网络流行 Cyber Hit ......................................... 30 3.11 11. 独立流行 Indie Pop ......................................... 30 3.12 12. 女子团体 Girl Group ......................................... 31 3.13 13. 男孩团体 Boy Band ......................................... 32 3.14 14. 青少年流行 Teen Pop ........................................ 32 3.15 15. 迷幻流行 Psychedelic Pop ...................................... 33 3.16 16. 氛围流行 Ambient Pop ....................................... 33 3.17 17. 阳光流行 Sunshine Pop ....................................... 34 3.18 18. 韩国抒情歌曲 Korean Ballad .................................... 34 3.19 19. 台湾民歌运动 Taiwan Folk Scene .................................. 34 3.20 20. 无伴奏合唱 A cappella ....................................... 36 3.21 21. 噪音流行 Noise Pop ......................................... 37 3.22 22. 都市流行 City Pop ......................................... -

Sculpture Instructions, Alphabetical Listing

Sculptures in the mail featured sponsor: Sculpture Instructions, alphabetical listing (with links to the original messages) Stars ( ) next to entries indicate that they contain graphical instructions. Title - (Author, Subject, Date, Time) ● Acrobats - (Simon James) ● Acrobats - (David G) ● Airplane - (Larry Moss) ● Alien - (Mark Burginger) ● Alligator - (Bruce Kalver) ● Alligator - (Kevin Young) ● Angel - (Donna Jaffke) ● Angel - (Troy Perry) ● Angel - (Tootsie the Clown) ● Ape -(Alan Simkins) http://www.balloonhq.com/faq/SculptureNames.html (1 of 17) [11/28/1999 1:27:58 PM] Sculptures in the mail ● Antler Hat - (Chris Lawton) ● Apples - (Bruce Kalver) ● Ariel (Little Mermaid) - (Lorna Paris) ● Arm Animal -(Dave Jarvis) ● Baboon -(Jim Batten) ● Ball in Balloon Toy - (Carol Warren) ● Ball in Balloon Toy - Missile Balloon -(Chris Maxwell) ● Ball-in-balloon toys - (Edward Cardinal) ● Balloon Juggling Balls - (Larry Hirsch) ● Balloon Trick - Norm Carpenter ● Balloon Tricks - Troy Perry ● Bananas - (Bruce Kalver) ● Banjo -(Larry Moss) ● Barney routine - (Michele Rothstein) ● Base - (Arla Albers) ● Base - (Troy Perry) ● Base for flower bouquet - (Arlene Powers) ● Baseball Hat - (Steven Hayden Brown) ● Baseball Player - (Mark Balzer) ● Basket - (Bruce Kalver) ● Basketball - (Popsicle the Clown) ● Basketball - (Fred Harshberger) ● Basketball - (Magic Mike) ● Basketball - (Mark Balzer) ● Basketball - (Mark Balzer) ● Basketball hoop - (Fred Harshberger) ● Basketball Player Hat - (Adrienne Vincent) ● Bass -(Sir Twist) ● Bat - (Larry Moss) ● Baz -

WDAM Radio's History of Jan & Dean

WDAM Radio's Hit Singles History Of Jan & Dean # Artist Title Chart Comments Position/Year 01 01 Jan & Arnie “Jennie Lee” #8/1958 Song inspired by a poster featuring a local, Hollywood burlesque performer, Virginia Lee Hicks, who was then performing as Jennie Lee, the "Bazoom Girl", at the New Follies Burlesk at 548 S. Main St, Los Angeles. 01A Billy Ward & His Dominoes “Jennie Lee” #55/1958 02 Jan & Arnie “Gas Money” #81/1958 03 Jan & Dean “Baby Talk” #10/1959 Initial pressings incorrectly credited “Jan & Arnie.” 03A Laurels “Baby Talk” –/1958 Original version. 03B Jan & Dean “She’s Still Talking Baby Talk” –/1962 Answer song. 04 Jan & Dean “There’s A Girl” #97/1959 05 Jan & Dean “Clementine” #65/1960 Released 2/8/1960. 05A Bobby Darin “Clementine” #21/1960 Released 3/21/1960. 05B Bing Crosby “Clementine” #20/1941 06 Jan & Dean “We Go Together” #53/1960 07 Crows – “Gee” “Gee” #13/1954 07A Jan & Dean “Gee” #81/1960 07B Pixies Three “Gee” #87/1964 08 Jan & Dean “Heart And Soul” #25/1961 Released 6/26/1961 08A Cleftones “Heart And Soul” #18/1961 Released 5/22/1961 08B Johnny Maddox & The “Heart And Soul” #57/1956 Rhythmasters 08C Four Aces “Heart And Soul” #11/1952 08D Larry Clinton & His Orchestra “Heart And Soul” #1/1938 From the film, A Song Is Born. Original version. [Vocal – Bea Wain] 08E Al Donahue & His Orchestra “Heart And Soul” #16/1938 [Vocal – Paula Kelly] 08F Eddy Duchin & His Orchestra “Heart And Soul” #12/1938 08G Eddy Duchin & His Orchestra “Riptide” #3/1934 Same melody as “Heart And Soul.” Label credits read [Vocal - Lew Sherwood & The “Dedicated To The M-G-M Film Riptide,” which starred DeMarco Sisters] Norma Shearer. -

John Tefteller's World's Rarest Records

John Tefteller’s World’s Rarest Records Address: P. O. Box 1727, Grants Pass, OR 97528-0200 USA Phone: (541) 476–1326 or (800) 955–1326 • FAX: (541) 476–3523 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.tefteller.com Auction closes Tuesday, September 17, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. See #65 See #78 Original 1960’s Surf / Hot Rod / Rockin’ Instrumental 45’s Auction 67. Chris Columbo And The Swinging Gentlemen — “Oh Yeah (Part 1)/ SPECIAL NOTE: The Beach Boys! (Part 2)” KING 5012 M- MB $20 68. King Coney And The Hot Dogs — This is my last Surf auction for a (See Insert on Next Page) “Ba-Pa-Da, Ba-Pa-Da/Ten, Two And Four” LEGRAND 1038 VG+ MB $10 while. Great Surf 45’s are just not turning up like they used to. 32. The Belaires — “Mr. Moto/Little Brown Jug” ARVEE 5034 MINT MB $25 I hope to be able to have ONE Surf auction next year, but that will depend on what I find. There are a number of lower- grade Surf 45’s in this auction 49. Bruce And Jerry — “Take This Pearl/ but please be advised that I Saw Her First” ARWIN 1003 MINT WHITE LABEL PROMO with Distributor almost everything graded VG+ stamp on B-side label, BRUCE JOHNSTON or even VG will play close to MB $50 50. Bruce And Terry — “Custom Machine/ Mint, as they have more visual Makaha At Midnight” COLUMBIA 42956 69. Jud Conlon Rhythmaires — “Headers VG MB $5 Frank/Wristpin Charlie” DRAG RACE 1001 issues rather than sound issues. -

Surf 45'S/Lp's

John Tefteller’s World’s Rarest Records Address: P. O. Box 1727, Grants Pass, OR 97528-0200 USA Phone: (541) 476–1326 or (800) 955–1326 • FAX: (541) 476–3523 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.tefteller.com Auction closes Tuesday, February 23, 2021 at 7:00 p.m. PT See #4 See #14 Original 1960’s Surf / Hot Rod / Rockin’ Instro LP’s & 45’s Auction I’ve seen! Made for Radio Station KFXM in SAN BERNARDINO, CALIFORNIA with DEAR POTENTIAL BIDDERS: lots of local Southern California Surf bands!!! MB $200 It has been a year and a half since my last Surf/Instro auction. With Covid and restricted travel, it has taken a LONG time to put together a SUPER RARE decent Surf/Instro auction. Yes, there are some LP’s in this auction, some very rare and collectable LP’s, including The Satans’ “Raising Surf / Rockin’ Instro / Hell” — the ONLY COPY I’ve ever seen! Hot Rod 45’s The 45’s have two MEGA RARITIES — The Nodaens “Beach Girl” 16. Mike Adams And The Red Jackets — “So Blue/For Me And My Gal” MARCO on Gold and Mel Taylor And The Ventures on Toppa — both of 103 M- Produced by Herb Alpert and Lou Adler MB $20 these are LEGENDARY RARE and offered by me for the FIRST TIME 9. Unknown — “The Monster Album” 17. Al And Nettie — “San Francisco Twist/ in all my 45+ years in records! DCP INTERNATIONAL DCL 3805 M-/M- Now You Know” GEDINSON’S 6159 M- WHITE LABEL PROMO COPY, Radio MB $20 Station call letters are written on the front 18. -

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for Transcribing and Compiling These 1960S WAKY Surveys!

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for transcribing and compiling these 1960s WAKY Surveys! WAKY TOP FORTY JANUARY 30, 1960 1. Teen Angel – Mark Dinning 2. Way Down Yonder In New Orleans – Freddy Cannon 3. Tracy’s Theme – Spencer Ross 4. Running Bear – Johnny Preston 5. Handy Man – Jimmy Jones 6. You’ve Got What It Takes – Marv Johnson 7. Lonely Blue Boy – Steve Lawrence 8. Theme From A Summer Place – Percy Faith 9. What Did I Do Wrong – Fireflies 10. Go Jimmy Go – Jimmy Clanton 11. Rockin’ Little Angel – Ray Smith 12. El Paso – Marty Robbins 13. Down By The Station – Four Preps 14. First Name Initial – Annette 15. Pretty Blue Eyes – Steve Lawrence 16. If I Had A Girl – Rod Lauren 17. Let It Be Me – Everly Brothers 18. Why – Frankie Avalon 19. Since You Broke My Heart – Everly Brothers 20. Where Or When – Dion & The Belmonts 21. Run Red Run – Coasters 22. Let Them Talk – Little Willie John 23. The Big Hurt – Miss Toni Fisher 24. Beyond The Sea – Bobby Darin 25. Baby You’ve Got What It Takes – Dinah Washington & Brook Benton 26. Forever – Little Dippers 27. Among My Souvenirs – Connie Francis 28. Shake A Hand – Lavern Baker 29. It’s Time To Cry – Paul Anka 30. Woo Hoo – Rock-A-Teens 31. Sand Storm – Johnny & The Hurricanes 32. Just Come Home – Hugo & Luigi 33. Red Wing – Clint Miller 34. Time And The River – Nat King Cole 35. Boogie Woogie Rock – [?] 36. Shimmy Shimmy Ko-Ko Bop – Little Anthony & The Imperials 37. How Will It End – Barry Darvell 38. -

Go for the Gold...Read! Louisiana Summer Reading Program, 1996. INSTITUTION Louisiana State Library, Baton Rouge

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 403 913 IR 056 290 AUTHOR White, Dorothy J., Ed. TITLE Go For the Gold...Read! Louisiana Summer Reading Program, 1996. INSTITUTION Louisiana State Library, Baton Rouge. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 270p.; For the 1995 manual, see ED 380 140. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Athletics; Childrens Art; Childrens Games; *Educational Games; Elementary Education; Elementary School Students; Handicrafts; Kindergarten; Kindergarten Children; *Learning Activities; *Library Services; Olympic Games; Poetry; Preschool Children; Preschool Education; Publicity; *Reading Programs; Songs; Story Telling; *Summer Programs; Toddlers IDENTIFIERS Clip Art; *Louisiana ABSTRACT A manual for the 1996 Louisiana Summer Reading Program is presented in five sections with an Olympic and sports-related theme and illustrations. An evaluation form, a 1996 monthly calendar, and clip art images are provided. The first section covers promotion and publicity, and contains facts about the Olympics, promotion ideas, and sample news releases. The next section contains program suggestions and recipes. Suggestions for decorating the library, including clip art designs, bookmarks, doorknob and bulletin board decorations, and resources for additional clip art designs are provided in 'the third section. The fourth section contains storytime planners divided into the following age categories: toddlers, preschool-kindergarten, first-third grades, fourth-fifth grades, and sixth grade. The fifth section comprises the majority of the document and provides activities; coloring pages and handouts; costumes; crafts; fingerplays; flannel boards; games, riddles, and puzzles; poems; puppets and puppet plays; songs; and stories. (Contains 463 references.) (SWC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Summer Songs.Qxd

Special Issue THE TOP SUMMER SONGS OF ALL TIME 1. SURFIN’ U.S.A.- Beach Boys 63 51. AQUARIUS / LET THE SUN SHINE IN - 5th Dimension 69 2. UNDER THE BOARDWALK - Drifters 64 52. GRAZING IN THE GRASS - Friends Of Distinction 69 / Hugh Masekela 68 3. HOT FUN IN THE SUMMERTIME - Sly and the Family Stone 69 53. ROCK THE BOAT - Hues Corporation 74 4. IN THE SUMMERTIME - Mungo Jerry 70 54. COME ON DOWN TO MY BOAT - Every Mother’s Son 67 5. SUMMERTIME - Billy Stewart 66 55. INDIAN LAKE - Cowsills 68 6. SUMMERTIME, SUMMERTIME - Jamies 58 56. RIDE CAPTAIN RIDE - Blues Image 70 7. SUMMER IN THE CITY - Lovin’ Spoonful 66 57. BRANDY (YOU’RE A FINE GIRL) - Looking Glass 72 8. SUMMER NIGHTS - Olivia Newton-John & John Travolta 78 58. SLOOP JOHN B / YOU’RE SO GOOD TO ME - Beach Boys 66 9. SUMMERTIME BLUES - Eddie Cochran 58 / Blue Cheer 68 / The Who 71 59. MIAMI - Will Smith 99 10. THOSE LAZY-HAZY-CRAZY DAYS OF SUMMER - Nat “King” Cole 63 60. DAYDREAM - Lovin’ Spoonful 66 11. HERE COMES SUMMER - Jerry Keller 59 61. CATCH A WAVE - Beach Boys 64 12. SURF CITY - Jan and Dean 63 62. GOOD DAY SUNSHINE - Beatles 66 13. WIPE OUT / SURFER JOE - Surfaris 63 63. CARIBBEAN QUEEN (NO MORE LOVE ON THE RUN) - Billy Ocean 84 14. HEAT WAVE - Martha and the Vandellas 63 / Linda Ronstadt 75 64. SUMMERTIME SUMMERTIME - Nocera 87 15. PARADISE BY THE DASHBOARD LIGHT - Meat Loaf 78 65. PLEASE DON’T TALK TO THE LIFEGUARD - Diane Ray / Andrea Carroll 63 16. -

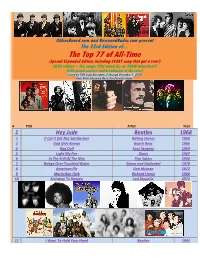

The Top 77 of All-Time

OldiesBoard.com and RewoundRadio.com present The 23rd Edition of… The Top 77 of All-Time (Special Expanded Edition including EVERY song that got a vote!) 2020 edition – the songs YOU voted for as YOUR favorites!!! With special analysis and breakdowns of the votes! Voted by YOU from November 2 through December 7, 2020 Each Voter Choosing Up to Ten Favorite Songs! # Title Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 4 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 5 Light My Fire Doors 1967 6 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 7 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 8 American Pie Don McLean 1972 9 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 10 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 11 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 12 Ain't No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 15 My Girl Temptations 1965 16 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 17 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 18 Beginnings Chicago 1971 19 Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In 5th Dimension 1969 20 Cherish Association 1966 21 Let It Be Beatles 1970 22 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 23 California Dreamin' Mamas and the Papas 1966 24 Morning Girl Neon Philharmonic 1969 25 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 26 She Loves You Beatles 1964 27 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 28 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 Mr Dieingly Sad Critters 1966 31 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 32 Nights In White