Open Akulkarni Dissertation.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Joe Rosochacki - Poems

Poetry Series Joe Rosochacki - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joe Rosochacki(April 8,1954) Although I am a musician, (BM in guitar performance & MA in Music Theory- literature, Eastern Michigan University) guitarist-composer- teacher, I often dabbled with lyrics and continued with my observations that I had written before in the mid-eighties My Observations are mostly prose with poetic lilt. Observations include historical facts, conjecture, objective and subjective views and things that perplex me in life. The Observations that I write are more or less Op. Ed. in format. Although I grew up in Hamtramck, Michigan in the US my current residence is now in Cumby, Texas and I am happily married to my wife, Judy. I invite to listen to my guitar works www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Dead Hand You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, Know when to walk away and know when to run. You never count your money when you're sittin at the table. There'll be time enough for countin' when the dealins' done. David Reese too young to fold, David Reese a popular jack of all trades when it came to poker, The bluffing, the betting, the skill that he played poker, - was his ace of his sleeve. He played poker without deuces wild, not needing Jokers. To bad his lungs were not flushed out for him to breathe, Was is the casino smoke? Or was it his lifestyle in general? But whatever the circumstance was, he cashed out to soon, he had gone to see his maker, He was relatively young far from being too old. -

Retrospektive Viennale 1998 CESTERREICHISCHES FILM

Retrospektive Viennale 1998 CESTERREICHISCHES FILM MUSEUM Oktober 1998 RETROSPEKTIVE JEAN-LUC GODARD Das filmische Werk IN ZUSAMMENARBEIT MIT BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE, LONDON • CINEMATHEQUE DE TOULOUSE • LA CINl-MATHfeQUE FRAN^AISE, PARIS • CINIiMATHkQUE MUNICIPALE DE LUXEMBOURG. LUXEMBURG FREUNDE DER DEUTSCHEN KINEMATHEK. BERLIN ■ INSTITUT FRAN^AIS DB VIENNE MINISTERE DES AFFAIRES ETRANGERES, PARIS MÜNCHNER STADTMUSEUM - FILMMUSEUM NATIONAL FILM AND TELEVISION ARCHIVE, LONDON STIFTUNG PRO HEI.VETIA, ZÜRICH ZYKLISCHES PROGRAMM - WAS IST FILM * DIE GESCHICHTE DES FILMISCHEN DENKENS IN BEISPIELEN MIT FILMEN VON STAN BRAKHAGE • EMILE COHL • BRUCE CONNER • WILLIAM KENNEDY LAURIE DfCKSON - ALEKSANDR P DOVSHENKO • MARCEL DUCHAMP • EDISON KINETOGRAPH • VIKING EGGELING; ROBERT J. FLAHERTY ROBERT FRANK • JORIS IVENS • RICHARD LEACOCK • FERNAND LEGER CIN^MATOGRAPHE LUMIERE • ETIENNE-JULES MAREY • JONAS MEKAS • GEORGES MELIUS • MARIE MENKEN • ROBERT NELSON • DON A. PENNEBAKER • MAN RAY • HANS RICHTER • LENI glEFENSTAHL • JACK SMITH • DZIGA VERTOV 60 PROGRAMME • 30 WOCHEN • JÄHRLICH WIEDERHOLT • JEDEN DIENSTAG ZWEI VORSTELLUNGEN Donnerstag, 1. Oktober 1998, 17.00 Uhr Marrfnuß sich den anderen leihen, sich jedoch Monsigny; Darsteller: Jean-Claude Brialy. UNE FEMME MARIEE 1964) Sonntag, 4. Oktober 1998, 19.00 Uhr Undurchsichtigkeit und Venvirrung. Seht, die Rea¬ Mittwoch, 7. Oktober 1998, 21.00 Uhr Raou! Coutard; Schnitt: Agnes Guiliemot; Die beiden vorrangigen Autoren der Gruppe Dziga sich selbst geben- Montaigne Sein Leben leben. Anne Colette, Nicole Berger Regie: Jean-Luc Godard; Drehbuch: Jean-Luc lität. metaphorisiert Godaiti nichtsonderlich inspi¬ Musik: Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, Franz Vertov. Jean-Luc Godard und Jean-Pierre Gönn, CHARLOTTE ET SON JULES (1958) VfVRE SA VIE. Die Heldin, die dies versucht: eine MASCULIN - FEMININ (1966) riert, em Strudel, in dem sich die Wege verlaufen. -

Jean-Luc Godard – Musicien

Jean-Luc Godard – musicien Jürg Stenzl Stenzl_Godard.indb 1 24.11.10 14:30 Jürg Stenzl, geb. 1942 in Basel, studierte in Bern und Paris, lehrte von 1969 bis 1991 als Musikhistoriker an der Universität Freiburg (Schweiz), von 1992 an in Wien und Graz und hatte seit Herbst 1996 bis 2010 den Lehrstuhl für Mu- sikwissenschaft an der Universität Salzburg inne. Zahlreiche Gastprofessuren, zuletzt 2003 an der Harvard University. Publizierte Bücher und über 150 Auf- sätze zur europäischen Musikgeschichte vom Mittelalter bis in die Gegenwart. Stenzl_Godard.indb 2 24.11.10 14:30 Jean-Luc Godard – musicien Die Musik in den Filmen von Jean-Luc Godard Jürg Stenzl Stenzl_Godard.indb 3 24.11.10 14:30 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung durch das Rektorat der Universität Salzburg, Herrn Rektor Prof. Dr. Heinrich Schmidinger. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-86916-097-9 © edition text + kritik im RICHARD BOORBERG VERLAG GmbH & Co KG, München 2010 Levelingstr. 6a, 81673 München www.etk-muenchen.de Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung, die nicht ausdrücklich vom Urheberrechtsgesetz zugelassen ist, bedarf der vorherigen Zustim- mung des Verlages. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Bearbeitungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen -

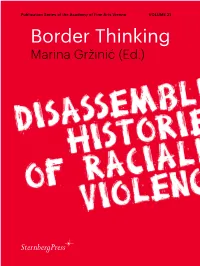

Border Thinking

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 21 Border Thinking Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) VOLUME 21 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present the latest volume in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna’s publication series. The series, published in cooperation with our highly com- mitted partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contemporary thought about art practices and theories. The volumes comprise contribu- tions on subjects that form the focus of discourse in art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is published in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the academy. Authors of high international repute are invited to make contributions that deal with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institute- specific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. All books in the series undergo a single blind peer review. International re- viewers, whose identities are not disclosed to the editors of the volumes, give an in-depth analysis and evaluation for each essay. The editors then rework the texts, taking into consideration the suggestions and feedback of the reviewers who, in a second step, make further comments on the revised essays. -

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de kunsten: audiovisuele kunsten Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Doctor of Arts: Audiovisual Arts Academic year 2017- 2018 Doctorandus: Stoffel Debuysere Promotors: Prof. Dr. Steven Jacobs, Ghent University, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Dr. An van. Dienderen, University College Ghent School of Arts Editor: Rebecca Jane Arthur Layout: Gunther Fobe Cover design: Gitte Callaert Cover image: Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep (1977). Courtesy of Charles Burnett and Milestone Films. This manuscript partly came about in the framework of the research project Figures of Dissent (KASK / University College Ghent School of Arts, 2012-2016). Research financed by the Arts Research Fund of the University College Ghent. This publication would not have been the same without the support and generosity of Evan Calder Williams, Barry Esson, Mohanad Yaqubi, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Sarah Vanhee, Christina Stuhlberger, Rebecca Jane Arthur, Herman Asselberghs, Steven Jacobs, Pieter Van Bogaert, An van. Dienderen, Daniel Biltereyst, Katrien Vuylsteke Vanfleteren, Gunther Fobe, Aurelie Daems, Pieter-Paul Mortier, Marie Logie, Andrea Cinel, Celine Brouwez, Xavier Garcia-Bardon, Elias Grootaers, Gerard-Jan Claes, Sabzian, Britt Hatzius, Johan Debuysere, Christa -

XIV:10 CONTEMPT/LE MÉPRIS (102 Minutes) 1963 Directed by Jean

March 27, 2007: XIV:10 CONTEMPT/LE MÉPRIS (102 minutes) 1963 Directed by Jean-Luc Godard Written by Jean-Luc Godard based on Alberto Moravia’s novel Il Disprezzo Produced by George de Beauregard, Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine Original music by Georges Delerue Cinematography by Raoul Coutard Edited by Agnès Guillemot and Lila Lakshamanan Brigitte Bardot…Camille Javal Michel Piccoli…Paul Javal Jack Palance…Jeremy Prokolsch Giogria Moll…Francesa Vanini Friz Lang…himself Raoul Coutard…Camerman Jean-Luc Godard…Lang’s Assistant Director Linda Veras…Siren Jean-Luc Godard (3 December 1930, Paris, France) from the British Film Institute website: "Jean-Luc Godard was born into a wealthy Swiss family in France in 1930. His parents sent him to live in Switzerland when the war broke out, but in the late 40's he returned to Paris to study ethnology at the Sorbonne. He became acquainted with Claude Chabrol, Francois Truffaut, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette, forming part of a group of passionate young film- makers devoted to exploring new possibilities in cinema. They were the leading lights of Cahiers du Cinéma, where they published their radical views on film. Godard's obsession with cinema beyond all else led to alienation from his family who cut off his allowance. Like the small time crooks he was to feature in his films, he supported himself by petty theft. He was desperate to put his theories into practice so he took a job working on a Swiss dam and used it as an opportunity to film a documentary on the project. -

Six Films / Jean-Luc Godard

Phrases presents the spoken language from six films by Jean- Luc Godard: Germany Nine Zero, The Kids Play Russian, JLG / JLG, 2 x 50 Years of French Cinema, For Ever Mozart and In Praise of Love. Completed between 1991 & 2001, during what has been called Godard’s “years of memory,” these films and videos were made alongside and in the shadow of his major work from that time, his monumental Histoire(s) du cinema, complementing and extending its themes. Like Histoire(s), they offer meditations on, among other things, the tides of history, the fate of nations, the work of memory, the power of cinema, and, ultimately, the nature of love. Gathered here, in written form, they are words without images: not exactly screenplays, not exactly poetry, something else entirely. Godard himself described them enigmatically: “Not books. Rather recollec- tions of films, without the photos or the uninteresting details… Only the spoken phrases. They offer a little prolongation. One even discov- ers things that aren’t in the film in them, which is rather powerful for a recollection. These books aren’t literature or cinema. Traces of a film…” In our era of ubiquitous streaming video, ebooks, and social media, these traces of cinema raise compelling questions for the future of media, cinematic, literary, and otherwise. isbn 978–1–9406251–7–1 www.contramundum.net Translation © 2016 Stuart Kendall. Library of Congress For Ever Mozart, jlg/jlg, Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Les enfants jouent à la Russie, Godard, Jean-Luc, 1930– Allemagne neuf zéro, 2x50 ans de cinéma français and Eloge de [For Ever Mozart, jlg/jlg, . -

Cinemed Meetings 22~24 Octobre 2019

CINEMED MEETINGS 22~24 OCTOBRE 2019 Cinemed Meetings est le rendez-vous des professionnels attentifs aux problématiques de production de l’aire méditerranéenne. Cinemed Meetings regroupe lors de trois journées dédiées aux professionnels : La 29e Bourse d’aide au développement 15 projets de longs métrages de fiction issus de 15 pays du bassin méditerranéen sélectionnés seront soutenus par leurs réalisatrices.teurs et productrices.teurs les mardi 22 et mercredi 23 octobre 2019 devant un jury de professionnels. Les soutenances sont ouvertes à tous les professionnels accrédités. Du Court au Long Pendant les trois jours des Cinemed Meetings, huit réalisateurs de courts métrages sélectionnés en compétition au Cinemed 2019 et en cours d’écriture d’un long métrage, rencontreront un jury de professionnels. L’objectif de ce dispositif est de faire découvrir au plus tôt des projets inédits et de les aider à se concrétiser en les mettant en relation avec d’éventuels producteurs ou coproducteurs. Ce nouveau dispositif renforce la volonté d’accompagnement et de soutien de Cinemed aux talents méditerranéens émergents. Les rencontres de la coproduction Les producteurs, vendeurs, financeurs, diffuseurs, représentants de société de post-production... sont invités à rencontrer lors de rendez-vous individuels les projets présentés aux Cinemed Meetings. SEE Factory 2019 En partenariat avec la Quinzaine des réalisateurs, La Factory 2019 à Cinemed : 13 pays, 10 réalisateurs, 5 courts métrages, 2 projets de longs métrages et un coup de projecteur sur les jeunes réalisateurs issus des pays de l’ex-Yougoslavie Talents en court au Cinemed L’opération Talents en court vise à favoriser une plus grande diversité culturelle et sociale dans le secteur du court métrage, en aidant le développement des projets de talents émergents pour qui l’accès au milieu professionnel est difficile, faute de formation et d’expérience significatives, en partenariat avec l’association Les Ami(e)s du Comedy Club, présidée par Jamel Debbouze, et Cinébanlieue. -

Snimajuce-Lokacije.Pdf

Elma Tataragić Tina Šmalcelj Bosnia and Herzegovina Filmmakers’ Location Guide Sarajevo, 2017 Contents WHY BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 3 FACTS AND FIGURES 7 GOOD TO KNOW 11 WHERE TO SHOOT 15 UNA-SANA Canton / Unsko-sanski kanton 17 POSAVINA CANTON / Posavski kanton 27 Tuzla Canton / Tuzlanski kanton 31 Zenica-DoboJ Canton / Zeničko-doboJski kanton 37 BOSNIAN PODRINJE CANTON / Bosansko-podrinJski kanton 47 CENTRAL BOSNIA CANTON / SrednJobosanski kanton 53 Herzegovina-neretva canton / Hercegovačko-neretvanski kanton 63 West Herzegovina Canton / Zapadnohercegovački kanton 79 CANTON 10 / Kanton br. 10 87 SARAJEVO CANTON / Kanton SaraJevo 93 EAST SARAJEVO REGION / REGION Istočno SaraJevo 129 BANJA LUKA REGION / BanJalučka regiJA 139 BIJELJina & DoboJ Region / DoboJsko-biJELJinska regiJA 149 TREBINJE REGION / TrebinJska regiJA 155 BRčKO DISTRICT / BRčKO DISTRIKT 163 INDUSTRY GUIDE WHAT IS OUR RECORD 168 THE ASSOCIATION OF FILMMAKERS OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 169 BH FILM 2001 – 2016 170 IMPORTANT INSTITUTIONS 177 CO-PRODUCTIONS 180 NUMBER OF FILMS PRODUCED 184 NUMBER OF SHORT FILMS PRODUCED 185 ADMISSIONS & BOX OFFICE 186 INDUSTRY ADDRESS BOOK 187 FILM SCHOOLS 195 FILM FESTIVALS 196 ADDITIONAL INFO EMBASSIES 198 IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS 204 WHERE TO STAY 206 1 Why BiH WHY BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA • Unspoiled natural locations including a wide range of natu- ral sites from mountains to seaside • Proximity of different natural sites ranging from sea coast to high mountains • Presence of all four seasons in all their beauty • War ruins which can be used -

Written and Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

FREEDOM DOESN'T COME CHEAP WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY JEAN-LUC GODARD France / 2010 / 101 min. / 1.78:1 / Dolby SR / In French w/ English subtitles A Lorber Films Release from Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 W. 39th St. Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contact: Rodrigo Brandao Kino Lorber, Inc. (212) 629-6880 ext. 12 [email protected] Short synopsis A symphony in three movements. THINGS SUCH AS: A Mediterranean cruise. Numerous conversations, in numerous languages, between the passengers, almost all of whom are on holiday... OUR EUROPE: At night, a sister and her younger brother have summoned their parents to appear before the court of their childhood. The children demand serious explanations of the themes of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. OUR HUMANITIES: Visits to six sites of true or false myths: Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Hellas, Naples and Barcelona. Long synopsis A symphony in three movements. THINGS SUCH AS: The Mediterranean, a cruise ship. Numerous conversations, in numerous languages, between the passengers, almost all of whom are on holiday... An old man, a war criminal (German, French, American we don’t know) accompanied by his grand daughter... A famous French philosopher (Alain Badiou); A representative of the Moscow police, detective branch; An American singer (Patti Smith); An old French policeman; A retired United Nations bureaucrat; A former double agent; A Palestinian ambassador; It’s a matter of gold, as it was before with the Argonauts, but what is seen (the image) is very different from what is heard (the word). OUR EUROPE: At night, a sister and her younger brother have summoned their parents to appear before the court of their childhood. -

Blind Vaysha Accidents, Blunders Showcase Sparkling a Head Disappears THEODORE USHEV | CANADA and Calamities International Talents

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL XL 2 PIFF XL Festival Venues Festival Program ADVANCE TICKET OUTLET 1119 SW Park Avenue at Main Welcome to the Northwest (inside the Portland Art Museum’s Film Center’s 40th Portland Mark Building) International Film Festival. This program is arranged by NW FILM CENTER (WH) section with the films in each Whitsell Auditorium section listed alphabetically. 1219 SW Park Avenue at Madison Showtimes and theater loca- (inside the Portland Art Museum) tions are listed at the bottom REGAL FOX TOWER (FOX) of each film descriptions. 846 SW Park Avenue at Taylor We hope the sections outlined below help you navigate your LAURELHURST THEATER (LH) PIFF experience. 2735 E Burnside Street CINEMA 21 (C21) MASTERS 4 616 NW 21st Avenue at Hoyt Exciting new works from some of VALLEY CINEMA (VC) the leading voices of national and 9360 SW Beaverton Hillsdale Hwy world cinema. EMPIRICAL THEATER NEW DIRECTORS 6 AT OMSI (OMSI) New and emerging filmmakers who 1945 SE Water Avenue represent the new generation of BAGDAD THEATER (BAG) master storytellers. 3702 SE Hawthorne Boulevard Cinema 21, Valley Theater, GLOBAL PANORAMA 9 Bagdad Theater, and Laurelhurst Award-winning films that tell stories Theater are all 21+ venues for that resonate beyond the unique films taking place after 5pm. cultures from which they emerge. Please check film times before bringing minors to screenings at these venues. No outside food DOCUMENTARY VIEWS 12 or beverages is allowed in any Fresh perspectives on the world theater. As a security policy, the we live in and the fascinating people, Portland Art Museum and Regal places, and stories that surround us.