1291): Considerations of Annalists in Genoa, Pisa, and Venice (13Th/14Th–16Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ievgen A. Khvalkov European University Institute, Florence’ S the 14Th - 15Th Century Genoese Colonies on the Black Sea

The Department of Medieval Studies of Central European University cordially invites you to the public lecture of the Faculty Research Seminar Ievgen A. Khvalkov European University Institute, Florence’ s The 14th - 15th Century Genoese Colonies on the Black Sea 17:30 p.m. on Wednesday, October 2, 2013 CEU–Faculty Tower #409 Budapest, V. Nádor u. 9. Self-portrait of notary Giacomo from Venice (ASV. NT. 733; notaio Iacobus quondam Guglielmi de Veneciis, capellanus ecclesie Sancti Simeoni) The thirteenth to fifteenth centuries were times of significant economic and social progress international long-distance trade. From its emergence around 1260s – 1270s and up to in the history of Europe. The development of industry and urban growth, the increasing role its fall to the Ottomans in 1475, the city was the main Genoese pivot in the area. This of trade and the increase in geographical knowledge resulted in an époque of Italian colonial resulted in the emergence of a mixed and cosmopolitan ethnic and cultural expansion. The Italian maritime republics, Genoa and Venice, became cradles of capitalism environment that gave birth to a new multicultural society comprising features and represent an early modern system of international long-distance trade. Besides being the characteristic of Western Europe, the Mediterranean area and the Near East as well as motherland of capitalism, Italy also introduced the phenomenon of colonialism into those of Central and Eastern Europe. The history of these societies and cultures may be European, and indeed world, history, since the patterns and models established by Italian regarded as one of the histories of unrealized potentials of intercultural exchange that colonialists later influenced the colonial experiences of other nations in the époque of Great began with the penetration of Italians to the Black Sea basin and stopped soon after the Geographic Discoveries. -

Diplomacy and Legislation As Instruments in the War Against Piracy in the Italian Maritime Republics (Genoa, Pisa and Venice)

MARIE-LUISE FAVREAU-LILIE Diplomacy and Legislation as Instruments in the War against Piracy in the Italian Maritime Republics (Genoa, Pisa and Venice) Amazingly enough, the significance of piracy as an impetus for the develop- ment of law in the Italian maritime trade cities Genoa, Pisa and Venice has yet to be the focus of systematic study. Neither has anyone thought to inquire what role diplomacy played in the maritime cities’ attempts to thwart the bane of piracy on the Mediterranean. Taking a look back at events transpiring in Pi- sa, probably in 1373, provides a perfect introduction to the topic of this paper. In that year, an esteemed Corsican, supposedly by the name of Colombano, bought two small ships. The buyer stated he intended to go on a trading expe- dition. Colombano readily swore the legally prescribed oath, but the Pisans were nonetheless suspicious and demanded he also present a guarantor as ad- ditional security. Colombano found the Pisan Gherardo Astaio, who was will- ing to vouch for him. In the event that Colombano broke his oath and set out to chase merchant ships instead of going on his trading expedition, Astaio would have to pay 800 florins. As it turned out, the distrust of the Pisan au- thorities was entirely justified: Colombano hired crews for both sailing vessels and in the early summer of 1374 proceeded to plunder in the waters off Pisa’s coast (“nel mare del commune di Pisa”) every ship he could get his hands on, regardless of origin, including ships from Pisa, from Pisa’s allies – cities and kingdoms –, as well as those of Pisa’s enemies. -

Download an Explorer Guide +

PORTOVENERE ITALY he ancient town of Portovenere looks T as if a brilliant impressionist painting has come to life. This romantic sentiment may not have been shared by those defending or assaulting the town over the past 1,000 years. However, today it can be said with relative cer- tainty that there is little chance of an attack by the Republic of Pisa, Saracen pirates, barbaric hordes or French Emperors. In other words, relax, have fun and enjoy your day in lovely, peaceful Portovenere. HISTORY With a population a little over 4,000, Portovenere is a small, Portovenere was founded by the Romans in the 1st century medieval town. It was built and defended by the Republic of Ge- BC. Known as Portus Veneris, it was built upon a promon- noa for nearly 800 years. This hilly point of land stretches north tory which juts out into the sea. As the empire slowly disinte- along the coast of the famous “Cinque Terre”. The town’s near- grated, Portovenere came under the eventual control of the est neighbor is the city of La Spezia, just east, around the cor- Byzantines. King Rothari of the Germanic Lombards took ner of the “Gulf of Poets”. So named for the great writers who the town, along with much of rest of Italy, the in the mid- praised, loved, lived and died in this beautiful region of Liguria, 600s. if they are somehow lost in time, Petrarch and Dante, Percy The struggle between the great Maritime Republics of Ge- Shelley and Lord Byron will forever be remembered here. -

Visualizing Conflict and Commerce in the Maritime Cities of Medieval Italy

Introdu ction Visualizing Conflict and Commerce in the Maritime Cities of Medieval Italy The maritime cities of Italy announced their presence in the Mediterranean, a political and economic arena already dominated by Muslim powers and the Byzantine Empire, through a combination of military campaigns and commer- cial exchange. This book will explore how participation in trade and warfare defined a distinct Mediterranean identity and visual culture for the cities of Amalfi, Salerno, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice in the eleventh to the mid-twelfth century. Each of these Italian locales formulated a unique visual manifestation of the relationship between commerce and conflict through the use of spolia or reused architectural elements, objects, and styles from past and foreign cul- tures. This aesthetic of appropriation with spolia as its central visual element was multivalent, mutable, and culturally inclusive, capable of incorporating multiple and disparate references from various peoples and places across the sea; it was thus the ideal visual medium to manifest the identity of the inhabit- ants of these Italian cities as warriors, traders, and influential forces in Medi- terranean economics, politics, and culture. In the creation and ornamentation of public architectural monuments, each city forged a spoliate aesthetic char- acterized by heterogeneous assemblages of appropriated luxury objects and building elements to reference the Mediterranean cultures that inspired the greatest antagonism, fear, admiration, or emulation. Conflict and Commerce in the Medieval Mediterranean It was in the time period immediately before and after the First Crusade that these seafaring cities formulated a Mediterranean identity that combined com- merce and conflict.1 In the eleventh century, the republics of Pisa and Genoa initiated a number of military campaigns against Muslim territories; their readiness to fight for the faith encouraged their early and eager participation in the First Crusade. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Proc. XVII International Congress of Vexillology Copyright @1999, Southern African Vexillological Assn. Peter Martinez (ed.) The vexillological heritage of the Knights of Saint John in Malta Adrian Strickland ABSTRACT: This paper illustrates some of the flags used by the Sovereign Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, Rhodes and Malta. We discuss the flags used during the period when the Knights ruled in Malta (between 1530 and 1798), together with some of the flags used by the Order in the present day. The final part of the paper illustrates flags presently in use in the Maltese islands, which derive from the flags of the Order. The illustrations for this paper appear on Plates 82-87. 1 The flag of the Order and the Maltese cross Before the famous battle of the Milvian Bridge in October 312AD^ the Roman Emperor Constantine is said to have dreamt of a sign by which he would conquer his enemy. In his dream the sign of a cross appeared with the motto In hoc signo vince. Later, the cross and this motto were reputed to have been borne on his battle standard, and a form of the cross was painted on the shields carried by his soldiers. There was something mystical about the strength of this sign and, indeed, the cross in all its variants was later to be included in the symbols and ensigns carried by Christian armies, a tradition which persists even to the present day. The Crusades, which later brought the flower of European chivalry together under one banner, were named after it, the banner of the cross. -

The Beauty of Liguria Published on Iitaly.Org (

The Beauty of Liguria Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) The Beauty of Liguria Azzurra Giorgi (April 29, 2013) Harbors, picturesque cities on the edges of cliffs, beautiful beaches and great cuisine are just some of the characteristics of Liguria, a region to discover. "If you come to Genoa, you can see all the palaces where the merchants and the bankers of the city lived. UNESCO decided that these palaces and the center of the city deserve to be a World Heritage Site,” said Anna Castellano, Council of the Department of Communications and City Promotion of Genoa, at an event organized by the Italian Government Tourist Board in New York Harbors, picturesque cities on the edges of cliffs, beautiful beaches and great cuisine: all this and more is Liguria [2]. Located in the north-western part of Italy, Liguria is a region that is not very well known abroad, but it has very authentic gems that deserve to be discovered. A land of commerce and navigators due to its position and having the port city of Genoa [3], one of the Maritime republics [4] together with Pisa [5], Amalfi [6] and Venice [7], as its capital, Liguria has always been a place of communication with other countries and cultures. The mixing of people, Page 1 of 3 The Beauty of Liguria Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) trade and traditions also reflects the geography of the entire region, characterized by mountains, hills and the sea. What characterize Liguria the most are its beveled shores that find in 'Cinque Terre [8]' their best expression. -

The Rise of Europe in the High Middle Ages: Reactions to Urban Economic Modernity 1050 - 1300

The Rise of Europe in The High Middle Ages: Reactions to Urban Economic Modernity 1050 - 1300 Dan Yamins History Club June 2013 Sunday, October 12, 14 Today: Strands that are common throughout Europe. Next time: Two Case Studies: Hanseatic League (Northern Europe) The Italian Maritime Republics (Southern Europe) Sunday, October 12, 14 Interrelated Themes During an “Age of Great Progress” Demographic: rise of cities and general population increase Socio-economic: Rise of the middle class, burghers and capitalism Commercial: intra-European land trade and European maritime powers Legal: Development of rights charters and challenge to feudal system Labor & production: Rise of guilds and craft specialization. The time during which Europe “took off” -- switching places with Asia / Middle East in terms of social dynamism. Development of Western modernity Sunday, October 12, 14 General population increase AREA 500 650 1000 1340 1450 For context: Greece/Balkans 5 3 5 6 4.5 Italy 4 2.5 5 10 7.3 Population levels of Europe during the Middle Ages can be Spain/Portugal 4 3.5 7 9 7 roughly categorized: Total - South 13 9 17 25 19 • 150–400 (Late Antiquity): population decline France/Low countries 5 3 6 19 12 • 400–1000 (Early Middle Ages): stable at a low level. British Isles 0.5 0.5 2 5 3 • 1000–1250 (High Middle Ages): population boom and Germany/Scandinavia 3.5 2 4 11.5 7.3 expansion. Total - West/Central 9 5.5 12 35.5 22.5 • 1250–1350 (Late Middle Ages): stable at a high level. Slavia. 5 3 • 1350–1420 (Late Middle Ages): steep decline (Black death) ---Russia 6 8 6 ---Poland/Lithuania 2 3 2 • 1420–1470 (Late Middle Ages): stable at a low level. -

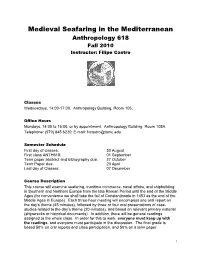

Medieval Seafaring in the Mediterranean Anthropology 618 Fall 2010 Instructor: Filipe Castro

Medieval Seafaring in the Mediterranean Anthropology 618 Fall 2010 Instructor: Filipe Castro Classes Wednesdays, 14:00-17:00. Anthropology Building, Room 105; Office Hours Mondays, 14:00 to 16:00, or by appointment. Anthropology Building, Room 105A. Telephone: (979) 845 6220; E-mail: [email protected]. Semester Schedule First day of classes: 30 August First class ANTH618: 01 September Term paper abstract and bibliography due: 27 October Term Paper due: 20 April Last day of Classes: 07 December Course Description This course will examine seafaring, maritime commerce, naval affairs, and shipbuilding in Southern and Northern Europe from the late Roman Period until the end of the Middle Ages (for convenience we shall take the fall of Constantinople in 1453 as the end of the Middle Ages in Europe). Each three-hour meeting will encompass one oral report on the day’s theme (45 minutes), followed by three or four oral presentations of case- studies related to the day’s theme (20 minutes), and based on relevant primary material (shipwrecks or historical documents). In addition, there will be general readings assigned to the whole class. In order for this to work, everyone must keep up with the readings, and everyone must participate in the discussion. The final grade is based 50% on oral reports and class participation, and 50% on a term paper. 1 General Readings Bass, G.F. A History of Seafaring; Based on Underwater Archaeology, London: Thames and Hudson, 1972. Collins, R. Early Medieval Europe 300-1000. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1999. Haywood, John. Dark Age Naval Power: A Reassessment of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Seafaring Activity. -

The Struggle for Sardinia in the Twelfth Century: Textual and Architectural Evidence from Genoa and Pisa

CHAPTER 8 The Struggle for Sardinia in the Twelfth Century: Textual and Architectural Evidence from Genoa and Pisa Henrike Haug In 1166, Genoese and Pisan ambassadors met at the court of Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa to hold negotiations about their respective rights to Sardinia.1 The two maritime republics, once allies against the Saracens in the eleventh century, became involved in an intense rivalry for markets and zones of influ- ence in the western Mediterranean from 1119 onwards.2 Sardinia was one of the main points of contention between them. Following the expulsion of the Arabs from the island in 1015/1016 by a joint Genoese and Pisan fleet, hostilities between the two city-states over possession of Sardinia became increasingly frequent over the course of the twelfth century.3 Each tried to expel the other 1 Enrico Besta, La Sardenga medioevale (Bologna, 1966 [1909]); Geo Pistarino, “Genova e la Sardegna nel secolo XII,” in La Sardegna nel mondo mediterraneo (Sassari, 1978), pp. 33–125; Alberto Boscolo, Sardegna, Pisa e Genova nel Medioevo (Genoa, 1978); and Geo Pistarino and Laura Balletto, “Inizio e sviluppo dei rapporti tra Genova e la Sardegna nel Medioevo,” Studi Genuensi 14 (1997), pp. 1–14. 2 The history of Corsica and Sardinia is largely connected to the history of the struggle be- tween Genoa and Pisa for supremacy on these islands between the tenth and thirteenth cen- turies. See Giuseppe Rossi-Sabatini, L’espansione di Pisa nel Mediterraneo fino alla Melloria (Florence, 1935), pp. 31–42 and Henry Bresc’s chapter in this volume. 3 This joint armada belonged to the early period of the battles waged by the two emerging communes against the Saracens. -

Shifting Significations of the Spolia Aesthetic

Conclusion Shifting Significations of the Spolia Aesthetic In the eleventh to mid-twelfth century, the interdependence of trade and war existed in a delicate but transitory equilibrium for the Italian maritime cities. The lasting achievement of the military campaigns of this time period was the establishment of these mercantile centers as essential participants in Mediter- ranean commercial exchange. What the cities fought for so aggressively came to fruition as they firmly asserted their presence in markets across the sea, exchanging goods with Muslim territories and Byzantium alike. Ultimately, the Italian mercantile cities were so successful that their fiercest competition came from one another as they vied with increasing hostility for supremacy in Mediterranean trade. The strategic use of violence, then, remained an effective means to open markets, protect financial assets and sovereign territories, and eliminate competitors. The aesthetic of appropriation employed in these mercantile centers, with its multicultural references, luxurious and exotic materials, and conflation of time and place in alluding to past and foreign cultures simultaneously, mani- fested a civic identity for each city based on a sense of Mediterranean belonging. The openness of spolia allowed each city to reference the cultures and locales with the most symbolic significance; the Byzantine Empire, Muslim territories, and ancient Rome all featured prominently in defining a unique visual culture for each Italian town. The maritime republics displayed their Mediterranean belonging and connection to other cultures by using materials goods acquired along the sea as architectural decoration. This was an inclusive and cumulative aesthetic that celebrated the fluidity and permeability of cultural boundaries in the Mediterranean. -

English Language Arts and Reading, Grade 4, (24) Research/Gathering Sources

Dear Educator, Originally the State of Texas exhibit for the 1968 World’s Fair held in San Antonio, the UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures (ITC) was simultaneously defined as a permanent research and production center dealing with the history of the peoples who make up Texas. Texas is, of course, a land, a state, once a nation, a huge and mixed ecology, a ritual happening, a stereotype, an economy, a state of mind, a way of life – and people. Twenty-four flags of nations representing Texas’ earliest settlement groups are outlined here. We attempt to answer some of the many questions your students may have about the flags of Texas, the flags of the world’s nations, and the flags flown in front of the UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures. Where did the colors and symbols of flags originate? Which flags have been changed since the early settlers left their counties of origin and which have stayed the same? How do the flags of the world’s nations differ? How are they similar? What are the reasons for these similarities? As educators, we at the ITC understand that you may need to adapt these lessons to fit the constructs of your classroom and the needs of your students. Please feel free to copy the handouts included or create your own. We hope that you will visit the UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures and continue to use our classroom resources to promote your students’ learning experiences. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us. Best, The Institute of Texan Cultures Education and Interpretation [email protected] www.texancultures.utsa.edu/learn UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures - Flags of Texas Settlers - Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Venetian Forest Law and the Conquest of Terraferma (1350-1476)

LAWYERS AND SAWYERS: VENETIAN FOREST LAW AND THE CONQUEST OF TERRAFERMA (1350–1476) Michael S. Beaudoin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University December 2014 ©2014 Michael S. Beaudoin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Michael S. Beaudoin Thesis Title: Lawyers and Sawyers: Venetian Forest Law and the Conquest of Terraferma (1350–1476) Date of Final Oral Examination: 30 July 2014 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Michael S. Beaudoin, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa M. Brady, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee David M. Walker, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Leslie Alm, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa M. Brady, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by John R. Pelton, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. DEDICATION Pella mia colomba iv AKNOWLEDGEMENTS An expression of gratitude is in order for the individuals and institutions that made this thesis a reality. First, I cannot express my appreciation enough to the three members of my thesis committee. These faculty members represent more than members of a committee. I had the privilege to study under each committee member. Their guidance and professionalism will serve as a model for my future roles inside and outside of academia.