Case 5:00-Cr-40104-JTM Document 610 Filed 04/06/09 Page 1 of 45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2003-Pickard-Lsd-Trial-Transcript-Gordontoddskinner-01.Pdf

Case 5:00-cr-40104-RDR Document 269 Filed 02/11/03 Page 1 of 131 1 " . 'I 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICt '"COURT,; '\ i FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS 2 TOPEKA, KANSAS I: 21-1 3 ::'~'":r"r"'" '. v ~.' , 4 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, :.. , . .-.-.... ------ Plaintiff,) ~ 5 ) vs. ) Case No. 6 ) 00-40104-01/02 WILLIAM L. PICKARD and } 7 CLYDE APPERSON! } ------------- Defendants. } 8 TRANSCRIPT OF VOLUME I OF THE TESTIMONY OF 9 GORDON TODD SKINNER HAD DURING TRIAL BEFORE 10 HONORABLE RICHARD D. ROGERS and a jury of 12 11 on January 28, 2003 12 13 APPEARANCES: 14 For the Plaintiff: Mr. Gregory G. Hough Asst. U.S. Attorney 15 290 Federal Building 444 Quincy Street 16 Topeka, Kansas 66683 17 For the Defendant: Mr. William Rork (Pickard) Rork Law Office 18 1321 SW Topeka Blvd. Topeka, Kansas 66612 19 20 For the Defendant: Mr. Mark Bennett (Apperson) Bennett, Hendrix & Moylan 21 5605 SW Barrington Court S Topeka, Kansas 66614 22 Court Reporter: Kelli Stewart! CSR, RPR 23 Nora Lyon & Associates 1515 South Topeka Avenue 24 Topeka, Kansas 66612 25 NORA LYON & ASSOCIATES, INC. 1515 S.W. Topeka Blvd., Topeka, KS 66612 Phone: (785) 232-2545 FAX: (785) 232-2720 ?Jo~ Case 5:00-cr-40104-RDR Document 269 Filed 02/11/03 Page 2 of 131 1 I N D E X ~ 2 Certificate------------------- 131 3 4 WIT N E S 5 ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: PAGE 6 GORDON TODD SKINNER 7 Direct Examination by Mr. Hough 3 8 9 10 11 12 13 '-' 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 NORA LYON & ASSOCIATES, INC. -

Neuropsychedelia

Neuropsychedelia The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain Nicolas Langlitz UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London Contents. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California Acknowledgments Vtl Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Introduction: Neuropsychopharmacology Langlitz, Nicolas, 1975-. Neuropsychedelia : the revival of hallucinogen as Spiritual Technology I research since the decade of the brain I Nicolas Langlitz. 1. Psychedelic Revival p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 2. Swiss Psilocybin and US Dollars 53 ISBN 978-0-520-27481-5 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-520-27482-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 3. The Varieties of Psychedelic Lab Experience I. Hallucinogenic drugs-Research. 2. Neuropsychopharmacology. 3. Hallucinogenic 4. Enacting Experimental Psychoses 2 drugs and religious experience. 1. Title. I3 BF209·H34L36 2013 - I54·4-dc23 5. Between Animality and Divinity I66 2012022916 6. Mystic Materialism 2°4 Manufactured in the United States of America Conclusion: Fieldwork in Perennial Philosophy 243 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 In keeping with a commitment to support Notes environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on 50-pound Bibliography Enterprise, a 30% post-consumer-waste, recycled, Index deinked fiber that is processed chlorine-free. -

US Censors LSD Trial, Double Life Sentence Without Parole

FACT exposé : US censors LSD trial, double life sentence without parole The Strange Trip and Fall of Leonard Pickard Criminal Injustice in the Heartland CJ Hinke [email protected] Freedom Against Censorship Thailand (FACT) http://facthai.wordpress.com More than 13 million Americans have tried LSD. US President John F. Kennedy himself engaged in LSD sessions with his lover Mary Pinchot with acid supplied by Timothy Leary. His brother, US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, was a vocal critic of the LSD ban; his wife, Ethel, was successfully treated for alcoholism in LSD sessions at Vancouver’s Hollywood Hospital, under the auspices of the International Association for Psychedelic Therapy, which claimed a success rate of 80%. Both brothers were assassinated; few know that Pinchot was also assassinated in her Washington apartment in 1964; her address book was never found. This article addresses another kind of assassination, life sentences for LSD. Nike Atlas Minuteman ICBM The heartland of the United States is riddled with hundreds of nuclear missile silos, now relics of the cold war. Many of these 20+ acre properties were sold to individuals including those doomsday proponents who saw them as the perfect place for survival come Armageddon. The silos have 47-ton fortified blast doors and a 66,000-pound battery bank. They also seem to be popular as a great modern location for server farms and hacker camps. Wamego, Kansas, is the heart of the heartland and welcomed the silos for their government employment opportunities in the country’s farm belt. Waumego was named after Potawatomie chief Waumego but all the Potawatomies were killed in the American Indian Wars in frontier massacres during the mid-1800s. -

3~/3I·-I!.-- -Against- Index No.: Rjino.: DAN HEINS, Doing Business As SHINING STAR ENTERPRISES

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF ALBANY PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, by ERIC T. SCHNEIDERMAN, Attorney General of the State ofNew York, Petitioner, AFFIRMATION 3~/3i·-I!.-- -against- Index No.: RJINo.: DAN HEINS, doing business as SHINING STAR ENTERPRISES, Respondent. DEANJ'JA R. NELSON, an attorney duly admitted to practice law in the State of New York, affirms the following under the penalties of perjury: 1. I am an Assistant Attorney General In Charge in the office of Eric T. Schneiderman, Attorney General of the State of New York (OAG), assigned to the Watertown Regional Office. I am fully familiar with the facts and circumstance of this proceeding, which are based on investigative materials contained in the files of the Attorney General's office. 2. I submit this Affirmation in support of Petitioner's application for an Order and Judgment permanently enjoining Respondent from engaging in deceptive, fraudulent and illegal business practices, requiring that Respondent produce an accounting of mislabeled and misbranded products sold and awarding and penalties and· costs to the State ofNew York 3. Unless otherwise indicated, I make this affirmation upon information and .belief, based upon my investigation, a review of documents and other evidence on file with the Department of Law. Annexed hereto in support of this petition are the fo Howing documents: Ex. I. Affidavit of Senior Investigator Chad Shelmidine, dated 7/6/12, together with Exhibits A-K; Ex. II. Affidavit of Dr. Maja Lundborg-Gray, M.D., FAAEM, FACEP, sworn to on July 5,2012, together with Exhibits A-G; Ex. -

BREAKING CONVENTION 4Th International Conference On

B REAKING C ONVENTION 4th International Conference on Psychedelic Consciousness 30 JUNE - 2 JULY 2017 UNIVERSITY OF GREENWICH, LONDON CONTENTS Front cover artwork: Cuteness Mania by Maura Holden Introduction 1 Abstracts (Alphabetically by Presenter) 2-33 Programme (Friday) 34-37 Programme (Saturday) 38-42 Programme (Sunday) 43-46 Installations 47 Special Events 48-49 Workshops & Cyberdelics Abstracts 50-52 Wasson Workshops 50 Cyberdelics Workshops 51 Film Festival 52-57 Visionary Art 58 Performances 59 Evening Entertainments 60 Invited Speaker & Committee Bios 61-71 Sponsors 72-79 Acknowledgements 80 University Map 81 Area Map 82 Venue Map 83-84 General Info 85 The Team 86 Safer Spaces Policy 87-89 Notes 90-91 BREAK TIMES - ALL DAYS 11:00 - 11:30 Break 13:00 - 14:30 Lunch 16:30 - 17:00 Break INTRODUCTION PRESENTER ABSTRACTS Adam A. Aronovich Sunday 2nd, 15:00, Eisner’s Entrance Hall Broadening Our Definitions Of Normalcy And Sanity: Crafting Alliances For Cognitive Liberty, Neurodiversity, And Non-Pathologizing Approaches To Mental Health. In common with prohibitive drug policies, western biopsychiatry tends to pathologise many expressions of human di- versity with narrow definitions of normalcy and sanity. An ethnographic approach to mental illness, however, unveils a variety of ways in which mental affliction is experienced, both cross-culturally and intra-culturally. Many non-ordinary experiences and states of awareness are not universally understood to be observable signs of mental disease but can be understood to be meaningful experiences -

In This Issue

EErowidA Psychoactiverow iPlantsd andEExtracts Chemicalsxtra Newslettercts June 2004 Number 6 e at Erowid are generally media referrers for the fi rst week after they were Erowid.org is a member-supported shy and tend to want to focus the published (spots usually occupied by the organization working to provide free, W project’s limited resources on search engines). data and technology rather than on promotion reliable and accurate information Despite our reticence, it is clear that or media attention. But last year we were about psychoactive plants and getting positive media attention helps bring convinced by a couple of friends that if we chemicals. in new support and introduces the site to continued to rebuff even friendly media people who aren’t familiar with it. It’s easy, The information on the site is inquiries, we were passively tipping the buried in Erowid Central, to imagine that a compilation of the experiences, scales towards those journalists who would everyone who’s interested in psychoactive words, and efforts of hundreds of write about the project without actually plants and chemicals already knows about individuals including parents, health talking to us. It seemed likely that these all the major online resources and at least professionals, doctors, therapists, people would be less sympathetic in their has stopped by Erowid in a search. But that chemists, researchers, teachers, writing than those who were kind enough to is clearly not the case. lawyers and those who choose to take “no” for an answer. use psychoactives. Erowid acts as As the project edges over 30,000 unique In early April, Seattle’s weekly alternative a publisher of new information as visitors per day and we consider the impact paper The Stranger published a full-page well as a library for the collection our site may have on those newly exposed editorial about Erowid. -

The History of MDMA As an Underground Drug in the United States, 1960–1979

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs ISSN: 0279-1072 (Print) 2159-9777 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujpd20 The History of MDMA as an Underground Drug in the United States, 1960–1979 Torsten Passie M.D., M.A. (Phil.) & Udo Benzenhöfer M.D., Ph.D. To cite this article: Torsten Passie M.D., M.A. (Phil.) & Udo Benzenhöfer M.D., Ph.D. (2016): The History of MDMA as an Underground Drug in the United States, 1960–1979, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2015.1128580 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2015.1128580 Published online: 03 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujpd20 Download by: [New York University] Date: 05 March 2016, At: 02:03 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2015.1128580 The History of MDMA as an Underground Drug in the United States, 1960–1979 Torsten Passie, M.D., M.A. (Phil.)a and Udo Benzenhöfer, M.D., Ph.D.b aProfessor and Visiting Scientist, Senckenberg Institute of History and Ethics in Medicine, Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; bProfessor, Senckenberg Institute of History and Ethics in Medicine, Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methylamphetamine, a.k.a. “ecstasy”) was first synthesized in 1912 Received 29 June 2015 and resynthesized more than once for pharmaceutical reasons before it became a popular Revised 17 October 2015 recreational drug. -

An Interview with William Leonard Pickard

Sea of Radiance: An Interview with William Leonard Pickard BY HENRIK DAHL Posted on April 16, 2017 The following long-form interview is the first extended Q&A with Harvard and UCLA drug policy researcher turned writer William Leonard Pickard dedicated to the topic of altered states of consciousness. Published on the anniversary of Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann’s discovery of the psychedelic properties of LSD on 16 April 1943, this rare interview touches upon alchemy, psychedelic literature, and the challenging art of describing altered states via literary prose. Also discussed are altruistic motives for making LSD, memory in relation to the psychedelic experience, and the recent appearance of potentially lethal research chemicals that have reportedly been sold as LSD to unwitting users. In case one is not familiar with his biographical data, William Leonard Pickard (born 1945) is serving two life sentences without the possibility of parole for purportedly manufacturing astronomical amounts of LSD. Imprisoned since 2000, the alleged psychedelic chemist was arrested for his involvement in the Wamego bust, aka the Kansas missile silo bust, in November of that year. According to the DEA, the bust is the largest LSD case in history. While drug information site Erowid has pointed out that the lab’s production appears to be vastly exaggerated,[1] DEA has continued as recently as October 2016 in an American national media broadcast to assert the immensity of the lab’s production. Retired DEA Special Agent Guy Hargreaves claims in the documentary that the lab had the capability to make 2.8 billion dosage units of LSD.[2] Pickard, who at trial denied any criminal activity in relation to the case, is currently serving his sentence at USP Tucson, a high- security prison in Arizona that houses over 1,800 prisoners. -

Copyrighted Material

CHAPTER 1 The Acid Casualty ne day in the fall of 2001, I realized that I hadn ’ t seen any LSD in an awfully long time. I was living on the Eastern O Shore of Maryland at the time, where the drug had been a fi xture of my social scene since the early nineties. Most of my peers had continued dosing through college or whatever they chose to do instead. Even some watermen and farmers I knew had tripped on occasion. Because most acid users don ’ t take the drug with any regularity — a trip here or there is the norm — its absence didn ’ t immediately regis- ter. It ’ s the kind of drug that appears in waves, so the inability to fi nd it at any given time could be chalked up to the vagaries of the illicit drug market. I began asking friends who were going to hippie happenings to look for the drug. Eventually, I had a network of people poking around for it at concerts and festivals across the country, as well as in towns whereCOPYRIGHTED you ’ d expect to fi nd it, MATERIAL such as Boulder and San Francisco. They found nothing — and no one who ’ d even seen a hit of LSD since sometime in 2001 — even at Burning Man, a gathering of thousands in the desert of Nevada. Strolling around Burning Man and being unable to fi nd acid is something like walking into a bar and fi nding the taps dry. ● ● ● 1 cc01.indd01.indd 1 55/2/09/2/09 111:39:001:39:00 AAMM 2 THIS IS YOUR COUNTRY ON DRUGS In the fall of 2002, I enrolled at the University of Maryland ’ s public - policy school in College Park, in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. -

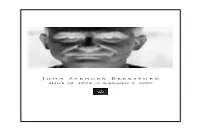

J O H N S P E N C E R B E R E S F O

J o h n S p e n c e r B e r e s f o r d March 28, 1924 — September 2, 2007 On the streets of Basel in 2006, with Dale Pendell, Christian Rätsch, and Robert Forte. John Beresford had a way about him that made you smile. He was a bright ray of sunshine, A happy soul, Always fighting the good fight, Always willing to listen, Never boastful. A free spirit, A warrior, He demanded attention. He wanted justice. He is liberated. We will all miss him. Photo on front cover ©1989, 2007 Marc Franklin. 29 John Beresford embodied many lives during this incarnation. He was a healer, a trailblazer, a gentle soul, a truth seeker, an activist, a messenger, a curator, and a warrior for justice. Healer – John earned his initial degree in medicine at London Hospital Medical College in 1952 and practiced in New York from 1953 to 1963 as a pediatrician. During the Vietnam War John refused to become a U.S. citi- zen and therefore was temporarily suspended from practicing medicine. Thus, John elected to work underground as a general practitioner in a walk- in clinic in Harlem. In 1974, John moved to Canada and entered the field of psychiatry. Trailblazer – John’s mission was to wake up the world. While working as Assistant Professor at New York Medical College, teaching pediatrics, John ordered a gram of pure LSD (lot# H-00047) from Sandoz Laboratories. Shortly afterwards, in 1963, John founded the Agora Scientific Trust: the world’s first research organization devoted to investigating LSD’s e¬ects. -

Erowid Extracts a Psychoactive Plants and Chemicals Newsletter

Erowid Extracts A Psychoactive Plants and Chemicals Newsletter June 2004 Number 6 e at Erowid are generally media referrers for the first week after they were Erowid.org is a member-supported shy and tend to want to focus the published (spots usually occupied by the organization working to provide free, project’s limited resources on search engines). reliable and accurate information Wdata and technology rather than on promotion Despite our reticence, it is clear that or media attention. But last year we were about psychoactive plants and getting positive media attention helps bring convinced by a couple of friends that if we chemicals. in new support and introduces the site to continued to rebuff even friendly media people who aren’t familiar with it. It’s easy, The information on the site is inquiries, we were passively tipping the buried in Erowid Central, to imagine that a compilation of the experiences, scales towards those journalists who would everyone who’s interested in psychoactive words, and efforts of hundreds of write about the project without actually plants and chemicals already knows about individuals including parents, health talking to us. It seemed likely that these all the major online resources and at least professionals, doctors, therapists, people would be less sympathetic in their has stopped by Erowid in a search. But that chemists, researchers, teachers, writing than those who were kind enough to is clearly not the case. lawyers and those who choose to take “no” for an answer. use psychoactives. Erowid acts as As the project edges over 30,000 unique In early April, Seattle’s weekly alternative a publisher of new information as visitors per day and we consider the impact paper The Stranger published a full-page well as a library for the collection our site may have on those newly exposed editorial about Erowid. -

The Notorious Hallucinogenic Drug LSD – That's 'Acid' Right?

LSD The notorious hallucinogenic drug (6aR,9R)-N,N-diethyl-7-methyl-4,6,6a,7,8,9- hexahydroindolo[4,3-fg]quinoline-9-carboxamide Paul May Bristol University Molecule of the Month December 1998 (Updated July 2017) Also available: JSMol version. LSD – that’s ‘acid’ right? Yes, technically it’s lysergic acid diethylamide, or just “acid”. It’s also known as LSD25, or colloquially as cubes, pearly gates, heavenly blue, royal blue, wedding bells, sugar, sugar lump, big D, blue acid, the chief, the hawk, instant Zen, etc. I’ll stick to LSD. How long have people known about it? Well, the story starts with a fungus called Claviceps purpurea which can grow parasitically on some cereals such as rye, particularly in wet summers. It forms fungal growths known as ergot. These growths resemble cereal grain and contain ergot alkaloids including lysergic acid, from which LSD is derived. In the Middle Ages, the flour used to make bread was sometimes contaminated with this infected grain. Many people died from ergot poisoning, some 40,000 during an outbreak in 994AD; some got gangrene, others had epileptic type fits and convulsions known as St Anthony’s fire, or experienced hallucinations. Ergotism may also explain the hysterical attacks in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692 that led to the Salem witch trials, though this is disputed, and it may even be one of the factors that led to the French Revolution in 1789. More recently, there was an outbreak in some parts of Southern Russia in Rye infected by ergot. The ergot kernel is the darker husk drooping down 1926-7, and in August 1951 there was a mysterious outbreak in the from the ear of rye.