3~/3I·-I!.-- -Against- Index No.: Rjino.: DAN HEINS, Doing Business As SHINING STAR ENTERPRISES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychoactive Plants Used in Designer Drugs As a Threat to Public Health

From Botanical to Medical Research Vol. 61 No. 2 2015 DOI: 10.1515/hepo-2015-0017 REVIEW PAPER Psychoactive plants used in designer drugs as a threat to public health AGNIESZKA RONDZISTy1, KAROLINA DZIEKAN2*, ALEKSANDRA KOWALSKA2 1Department of Humanities in Medicine Pomeranian Medical University Chłapowskiego 11 70-103 Szczecin, Poland 2Department of Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine Institute of Natural Fibers and Medicinal Plants Kolejowa 2 62-064 Plewiska, Poland *corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Summary Based on epidemiologic surveys conducted in 2007–2013, an increase in the consumption of psychoactive substances has been observed. This growth is noticeable in Europe and in Poland. With the ‘designer drugs’ launch on the market, which ingredients were not placed on the list of controlled substances in the Misuse of Drugs Act, a rise in the number and diversity of psychoactive agents and mixtures was noticed, used to achieve a different state of mind. Thus, the threat to the health and lives of people who use them has grown. In this paper, the authors describe the phenomenon of the use of plant psychoactive sub- stances, paying attention to young people who experiment with new narcotics. This article also discusses the mode of action and side effects of plant materials proscribed under the Misuse of Drugs Act in Poland. key words: designer drugs, plant materials, drugs, adolescents INTRODUCTION Anthropological studies concerning preliterate societies have shown that psy- choactive substances have been used for ages. On the individual level, they help to Herba Pol 2015; 61(2): 73-86 A. Rondzisty, K. -

Oxypertine (BAN, USAN, Rinn) However, US Licensed Product Information Recommends the Fol- Be Given Rectally in the Presence of Colitis

Oxazepam/Penfluridol 1015 Oxypertine (BAN, USAN, rINN) However, US licensed product information recommends the fol- be given rectally in the presence of colitis. Old paraldehyde must lowing maximum doses: Oksipertiini; Oxipertin; Oxipertina; Oxypertinum; Win-18501- never be used. 2. 5,6-Dimethoxy-2-methyl-3-[2-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)ethyl]- • CC 50 to 80 mL/minute: 6 mg once daily Paraldehyde must be well diluted before oral or rectal use; if it is deemed essential to give paraldehyde intravenously it must be indole. • CC 10 to 50 mL/minute: 3 mg once daily Paliperidone has not been studied in patients with a CC of less well diluted and given very slowly with extreme caution (see Оксипертин than 10 mL/minute; UK product information does not recom- also Adverse Effects, above and Uses, below). Intramuscular in- C23H29N3O2 = 379.5. mend its use in such patients. jections may be given undiluted but care should be taken to avoid CAS — 153-87-7 (oxypertine); 40523-01-1 (oxypertine nerve damage. Plastic syringes should be avoided (see Incompat- hydrochloride). Preparations ibility, above). ATC — N05AE01. Proprietary Preparations (details are given in Part 3) ATC Vet — QN05AE01. Cz.: Invega; Fr.: Invega; Port.: Invega; UK: Invega; USA: Invega. Interactions The sedative effects of paraldehyde are enhanced by CNS de- pressants such as alcohol, barbiturates, and other sedatives. A H Paraldehyde few case reports suggest that disulfiram may enhance the toxicity H3CO of paraldehyde; use together is not recommended. N Paracetaldehyde; Paraldehid; Paraldehidas; Paraldehído; Paralde- Pharmacokinetics CH3 hit; Paraldehyd; Paraldéhyde; Paraldehydi; Paraldehydum. The Paraldehyde is generally absorbed readily, although absorption is H CO trimer of acetaldehyde; 2,4,6-Trimethyl-1,3,5-trioxane. -

Effect of Wine and Vinegar Processing of Rhizoma Corydalis on the Tissue Distribution of Tetrahydropalmatine, Protopine and Dehydrocorydaline in Rats

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Michigan Tech Publications 1-18-2012 Effect of wine and vinegar processing of Rhizoma Corydalis on the tissue distribution of tetrahydropalmatine, protopine and dehydrocorydaline in rats Zhiying Dou Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Kefeng Li Michigan Technological University Ping Wang Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Liu Cao Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Dou, Z., Li, K., Wang, P., & Cao, L. (2012). Effect of wine and vinegar processing of Rhizoma Corydalis on the tissue distribution of tetrahydropalmatine, protopine and dehydrocorydaline in rats. Molecules, 17(1), 951-970. http://doi.org/10.3390/molecules17010951 Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p/1969 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Biology Commons Molecules 2012, 17, 951-970; doi:10.3390/molecules17010951 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Article Effect of Wine and Vinegar Processing of Rhizoma Corydalis on the Tissue Distribution of Tetrahydropalmatine, Protopine and Dehydrocorydaline in Rats Zhiying Dou 1,*, Kefeng Li 2, Ping Wang 1 and Liu Cao 1 1 College of Chinese Materia Medica, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 300193, China 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +86-22-5959-6235. Received: 29 November 2011; in revised form: 5 January 2012 / Accepted: 9 January 2012 / Published: 18 January 2012 Abstract: Vinegar and wine processing of medicinal plants are two traditional pharmaceutical techniques which have been used for thousands of years in China. -

Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca Analogues from the Late Bronze Age

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 104–116 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.013 First published online July 25, 2019 Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca analogues from the Late Bronze Age MATTHEW CLARK* School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), Department of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, University of London, London, UK (Received: October 19, 2018; accepted: March 14, 2019) In this article, the origins of the cult of the ritual drink known as soma/haoma are explored. Various shortcomings of the main botanical candidates that have so far been proposed for this so-called “nectar of immortality” are assessed. Attention is brought to a variety of plants identified as soma/haoma in ancient Asian literature. Some of these plants are included in complex formulas and are sources of dimethyl tryptamine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other psychedelic substances. It is suggested that through trial and error the same kinds of formulas that are used to make ayahuasca in South America were developed in antiquity in Central Asia and that the knowledge of the psychoactive properties of certain plants spreads through migrants from Central Asia to Persia and India. This article summarizes the main arguments for the botanical identity of soma/haoma, which is presented in my book, The Tawny One: Soma, Haoma and Ayahuasca (Muswell Hill Press, London/New York). However, in this article, all the topics dealt with in that publication, such as the possible ingredients of the potion used in Greek mystery rites, an extensive discussion of cannabis, or criteria that we might use to demarcate non-ordinary states of consciousness, have not been elaborated. -

Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 BR 111 / 2017 The Minister responsible for health, in exercise of the power conferred by section 48A(1) of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979, makes the following Order: Citation 1 This Order may be cited as the Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017. Repeals and replaces the Third and Fourth Schedule of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 2 The Third and Fourth Schedules to the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 are repealed and replaced with— “THIRD SCHEDULE (Sections 25(6); 27(1))) DRUGS OBTAINABLE ONLY ON PRESCRIPTION EXCEPT WHERE SPECIFIED IN THE FOURTH SCHEDULE (PART I AND PART II) Note: The following annotations used in this Schedule have the following meanings: md (maximum dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered at any one time. 1 PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 mdd (maximum daily dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance that is contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered in any period of 24 hours. mg milligram ms (maximum strength) i.e. either or, if so specified, both of the following: (a) the maximum quantity of the substance by weight or volume that is contained in the dosage unit of a medicinal product; or (b) the maximum percentage of the substance contained in a medicinal product calculated in terms of w/w, w/v, v/w, or v/v, as appropriate. -

Supporting Information a Analysed Substances

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Analyst. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2020 List of contents: Tab. A1 Detailed list and classification of analysed substances. Tab. A2 List of selected MS/MS parameters for the analytes. Tab. A1 Detailed list and classification of analysed substances. drug of therapeutic doping agent analytical standard substance abuse drug (WADA class)* supplier (+\-)-amphetamine ✓ ✓ S6 stimulants LGC (+\-)-methamphetamine ✓ S6 stimulants LGC (+\-)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) ✓ S6 stimulants LGC methylhexanamine (4-methylhexan-2-amine, DMAA) S6 stimulants Sigma cocaine ✓ ✓ S6 stimulants LGC methylphenidate ✓ ✓ S6 stimulants LGC nikethamide (N,N-diethylnicotinamide) ✓ S6 stimulants Aldrich strychnine S6 stimulants Sigma (-)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) ✓ ✓ S8 cannabinoids LGC (-)-11-nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC-COOH) S8 cannabinoids LGC morphine ✓ ✓ S7 narcotics LGC heroin (diacetylmorphine) ✓ ✓ S7 narcotics LGC hydrocodone ✓ ✓ Cerillant® oxycodone ✓ ✓ S7 narcotics LGC (+\-)-methadone ✓ ✓ S7 narcotics Cerillant® buprenorphine ✓ ✓ S7 narcotics Cerillant® fentanyl ✓ ✓ S7 narcotics LGC ketamine ✓ ✓ LGC phencyclidine (PCP) ✓ S0 non-approved substances LGC lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) ✓ S0 non-approved substances LGC psilocybin ✓ S0 non-approved substances Cerillant® alprazolam ✓ ✓ LGC clonazepam ✓ ✓ Cerillant® flunitrazepam ✓ ✓ LGC zolpidem ✓ ✓ LGC VETRANAL™ boldenone (Δ1-testosterone / 1-dehydrotestosterone) ✓ S1 anabolic agents (Sigma-Aldrich) -

Review Article Small Molecules from Nature Targeting G-Protein Coupled Cannabinoid Receptors: Potential Leads for Drug Discovery and Development

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2015, Article ID 238482, 26 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/238482 Review Article Small Molecules from Nature Targeting G-Protein Coupled Cannabinoid Receptors: Potential Leads for Drug Discovery and Development Charu Sharma,1 Bassem Sadek,2 Sameer N. Goyal,3 Satyesh Sinha,4 Mohammad Amjad Kamal,5,6 and Shreesh Ojha2 1 Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, P.O. Box 17666, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, UAE 2Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, P.O. Box 17666, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, UAE 3DepartmentofPharmacology,R.C.PatelInstituteofPharmaceuticalEducation&Research,Shirpur,Mahrastra425405,India 4Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA 90059, USA 5King Fahd Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 6Enzymoics, 7 Peterlee Place, Hebersham, NSW 2770, Australia Correspondence should be addressed to Shreesh Ojha; [email protected] Received 24 April 2015; Accepted 24 August 2015 Academic Editor: Ki-Wan Oh Copyright © 2015 Charu Sharma et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The cannabinoid molecules are derived from Cannabis sativa plant which acts on the cannabinoid receptors types 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2) which have been explored as potential therapeutic targets for drug discovery and development. Currently, there are 9 numerous cannabinoid based synthetic drugs used in clinical practice like the popular ones such as nabilone, dronabinol, and Δ - tetrahydrocannabinol mediates its action through CB1/CB2 receptors. -

A Systematic Review on Main Chemical Constituents of Papaver Bracteatum

Journal of Medicinal Plants A Systematic Review on Main Chemical Constituents of Papaver bracteatum Soleymankhani M (Ph.D. student), Khalighi-Sigaroodi F (Ph.D.)*, Hajiaghaee R (Ph.D.), Naghdi Badi H (Ph.D.), Mehrafarin A (Ph.D.), Ghorbani Nohooji M (Ph.D.) Medicinal Plants Research Center, Institute of Medicinal Plants, ACECR, Karaj, Iran * Corresponding author: Medicinal Plants Research Center, Institute of Medicinal Plants, ACECR, P.O.Box: 33651/66571, Karaj, Iran Tel: +98 - 26 - 34764010-9, Fax: +98 - 26-34764021 E-mail: [email protected] Received: 17 April 2013 Accepted: 12 Oct. 2014 Abstract Papaver bracteatum Lindly (Papaveraceae) is an endemic species of Iran which has economic importance in drug industries. The main alkaloid of the plant is thebaine which is used as a precursor of the semi-synthetic and synthetic compounds including codeine and naloxone, respectively. This systematic review focuses on main component of Papaver bracteatum and methods used to determine thebaine. All studies which assessed the potential effect of the whole plant or its extract on clinical or preclinical studies were reviewed. In addition, methods for determination of the main components, especially thebaine, which have been published from 1948 to March 2013, were included. Exclusion criteria were agricultural studies that did not assess. This study has listed alkaloids identified in P. bracteatum which reported since 1948 to 2013. Also, the biological activities of main compounds of Papaver bracteatum including thebaine, isothebaine, (-)-nuciferine have been reviewed. As thebaine has many medicinal and industrial values, determination methods of thebaine in P. bracteatum were summarized. The methods have being used for determination of thebaine include chromatographic (HPLC, GC and TLC) and non chromatographic methods. -

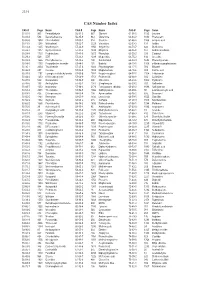

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Potentially Hazardous Drug Interactions with Psychotropics Ben Chadwick, Derek G

Chadwick et al Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (2005), vol. 11, 440–449 Potentially hazardous drug interactions with psychotropics Ben Chadwick, Derek G. Waller and J. Guy Edwards Abstract Of the many interactions with psychotropic drugs, a minority are potentially hazardous. Most interactions are pharmacodynamic, resulting from augmented or antagonistic actions at a receptor or from different mechanisms in the same tissue. Most important pharmacokinetic interactions are due to effects on metabolism or renal excretion. The major enzymes involved in metabolism belong to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system. Genetic variation in the CYP system produces people who are ‘poor’, ‘extensive’ or ‘ultra-rapid’ drug metabolisers. Hazardous interactions more often result from enzyme inhibition, but the probability of interaction depends on the initial level of enzyme activity and the availability of alternative metabolic routes for elimination of the drug. There is currently interest in interactions involving uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases and the P-glycoprotein cell transport system, but their importance for psychotropics has yet to be defined. The most serious interactions with psychotropics result in profound sedation, central nervous system toxicity, large changes in blood pressure, ventricular arrhythmias, an increased risk of dangerous side-effects or a decreased therapeutic effect of one of the interacting drugs. A drug interaction, defined as the modification of habits, problems related to polypharmacy are likely the action of one drug by another, can be beneficial to grow. or harmful, or it can have no significant effect. An There are numerous known and potential inter- appreciation of clinically important interactions is actions with psychotropic drugs, and many of them becoming increasingly necessary with the rising use do not have clinically significant consequences. -

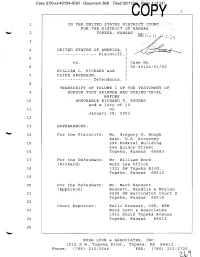

2003-Pickard-Lsd-Trial-Transcript-Gordontoddskinner-01.Pdf

Case 5:00-cr-40104-RDR Document 269 Filed 02/11/03 Page 1 of 131 1 " . 'I 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICt '"COURT,; '\ i FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS 2 TOPEKA, KANSAS I: 21-1 3 ::'~'":r"r"'" '. v ~.' , 4 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, :.. , . .-.-.... ------ Plaintiff,) ~ 5 ) vs. ) Case No. 6 ) 00-40104-01/02 WILLIAM L. PICKARD and } 7 CLYDE APPERSON! } ------------- Defendants. } 8 TRANSCRIPT OF VOLUME I OF THE TESTIMONY OF 9 GORDON TODD SKINNER HAD DURING TRIAL BEFORE 10 HONORABLE RICHARD D. ROGERS and a jury of 12 11 on January 28, 2003 12 13 APPEARANCES: 14 For the Plaintiff: Mr. Gregory G. Hough Asst. U.S. Attorney 15 290 Federal Building 444 Quincy Street 16 Topeka, Kansas 66683 17 For the Defendant: Mr. William Rork (Pickard) Rork Law Office 18 1321 SW Topeka Blvd. Topeka, Kansas 66612 19 20 For the Defendant: Mr. Mark Bennett (Apperson) Bennett, Hendrix & Moylan 21 5605 SW Barrington Court S Topeka, Kansas 66614 22 Court Reporter: Kelli Stewart! CSR, RPR 23 Nora Lyon & Associates 1515 South Topeka Avenue 24 Topeka, Kansas 66612 25 NORA LYON & ASSOCIATES, INC. 1515 S.W. Topeka Blvd., Topeka, KS 66612 Phone: (785) 232-2545 FAX: (785) 232-2720 ?Jo~ Case 5:00-cr-40104-RDR Document 269 Filed 02/11/03 Page 2 of 131 1 I N D E X ~ 2 Certificate------------------- 131 3 4 WIT N E S 5 ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: PAGE 6 GORDON TODD SKINNER 7 Direct Examination by Mr. Hough 3 8 9 10 11 12 13 '-' 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 NORA LYON & ASSOCIATES, INC. -

January 2020 Sanctions List Full

GLOBAL LIST OF INELIGIBLE PERSONS Period of Date of Discipline Date of Ineligibility Lifetime Infraction Name Nationality Role Sex Discipline 2 Sanction Disqualification ADRV Rules ADRV Notes Description Birth 1 Infraction until Ban? Type of results ABAKUMOVA, Maria 15/01/1986 RUS athlete F Javelin Throws 21/08/2008 4 years 17/05/2020 From 21.08.08 to No Doping Presence,Use Dehydrochloromethyltestos In competition test, XXIX Olympic ineligibility 20.08.12 terone games, Beijing, CHN ABDOSH, Ali 25/08/1987 ETH athlete M Long Distance 24/12/2017 4 years 04/02/2022 Since 24-12-2017 No Doping Presence,Use Salbutamol In competition test, 2017 Baoneng (3000m+) ineligibility Guangzhou Huangpu Marathon , ACHERKI, Mounir 09/02/1981 FRA athlete M 1500m Middle Distance 01/01/2014 4 years 15/04/2021 Since 01-01-2014 No Doping Use,Possessio Use or Attempted Use by an IAAF Rule 32.2(b) Use of a prohibited (800m-1500m) ineligibility n Athlete of a Prohibited substance ADAMCHUK, Mariya 29/05/2000 UKR athlete F Long Jump Jumps 03/06/2018 4 years 16/08/2022 Since 03.06.18 No Doping Presence,Use Benzoylecgonine In competition test, XXI Cross Citta ineligibility di Novi Ligure, Novi Ligure, ITA ADEKOYA, Kemi 16/01/1993 BRN athlete F 400m Sprints (400m or 24/08/2018 4 years 25/11/2022 Since 24.08.18 No Doping Presence,Use Stanozolol Out-of-competition test, Jakarta, IDN Hurdles less) ineligibility ADELOYE, Tosin 07/02/1996 NGR athlete F 400m Sprints (400m or 24/07/2015 8 years 23/07/2023 Since 24-07-2015 No Doping Presence,Use Exogenous Steroids In competition