An Interview with William Leonard Pickard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychoactive Substances and Transpersonal States

TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH REVIEW: PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES AND TRANSPERSONAL STATES David Lukoff San Francisco, California Robert Zanger Los Angeles, California Francis Lu San Francisco, California This "Research Review" covers recent trends in researching psychoactive substances and trans personal states of conscious ness during the past ten years. In keeping with the stated goals of this section of the Journal to promote research in transpersonal psychology, the focus is on the methods and trends designs which are being employed in investigations rather than during the findings on this topic. However, some recently published the books and monographs provide good summaries of the recent last findings relevant to understanding psychoactive substances ten (Cohen & Krippner, 1985b; Dobkin de Rios, 1984;Dobkin de years Rios & Winkelman, 1989b; Ratsch, 1990; Reidlinger, 1990). Because researching psychoactive substances is most broadly a cross-disciplinary venture, only a small portion of the research reviewed below was conducted by persons who consider The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Bruce Flath, head librarian at the California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco in conducting the computer bibliographic searches used in preparation of this article. The authors also wish to thank Marlene Dobkin de Rios, Stanley Krippner, Christel Lukoff, Dennis McKenna, Terence McKenna, Ralph Metzner, Donald Rothberg and Ilene Serlin for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. Copyright © 1990 Transpersonal Institute The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 1990, Vol. 22, No.2 107 themselves transpersonal psychologists. As Vaughan (1984) has noted, "The transpersonal perspective is a meta-perspec tive, an attempt to learn from all different disciplines . emerging from the needed integration of ancient wisdom and modern science. -

Eb07 REBIRTH-1.Pdf

REBIRTH: The Psychedelic Movement Comes Of Age In the End I was cast out of the alchemists’ den, a lost mystic exile from the beats, wandering the naked streets of Basel at dawn and transmitting a lovely fix. I was high on acid, a green tab of Hofmann’s bicycle wheel I had rever- ently acquired from the Californian High Priest nights before, high in the hotel room overlooking the tram depot opposite the Basel Congress Centre. Site of the conference diabolique with Dr. Albert Hofmann, the 100 year old Alche- mist that birthed LSD - the ‘Problem Child’ that switched on the world. Now: cloudbanks are/ rolling/ blooming/ shifting overhead and as they open up and become for me everything else is doing the same – trees, cars, people - especially people. These beautiful marionette citizens of Basel, heading off to work, rugged up against the winter chill. They are polite, cool, efficiently progressing through the basic programs of larval life. Light glistens past a woman on the second floor balcony of an apartment block as she shakes out a blanket. Down below, surrounded by layers of white, white snow, a middle-aged man is walking his dog. He waits patiently, well trained, as it sniffs a pole. They are radiating energy signatures that overlap like kaleidoscope pictures and sink deep into me. You know this feeling, the current. A stream of energy is bubbling within you straight from the source, and the more you let go and let it rise up and blossom in/ from you, the deeper in you go. -

Psychedelic Gospels

The Psychedelic Gospels The Psychedelic Gospels The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity Jerry B. Brown, Ph.D., and Julie M. Brown, M.A. Park Street Press Rochester, Vermont • Toronto, Canada Park Street Press One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.ParkStPress.com Park Street Press is a division of Inner Traditions International Copyright © 2016 by Jerry B. Brown and Julie M. Brown All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Note to the Reader: The information provided in this book is for educational, historical, and cultural interest only and should not be construed in any way as advocacy for the use of hallucinogens. Neither the authors nor the publishers assume any responsibility for physical, psychological, legal, or any other consequences arising from these substances. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [cip to come] Printed and bound in XXXXX 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Text design and layout by Priscilla Baker This book was typeset in Garamond Premier Pro with Albertus and Myriad Pro used as display typefaces All Bible quotations are from the King James Bible Online. A portion of proceeds from the sale of this book will support the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Founded in 1986, MAPS is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and educational organization that develops medical, legal, and cultural contexts for people to benefit from the careful uses of psychedelics and marijuana. -

2003-Pickard-Lsd-Trial-Transcript-Gordontoddskinner-01.Pdf

Case 5:00-cr-40104-RDR Document 269 Filed 02/11/03 Page 1 of 131 1 " . 'I 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICt '"COURT,; '\ i FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS 2 TOPEKA, KANSAS I: 21-1 3 ::'~'":r"r"'" '. v ~.' , 4 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, :.. , . .-.-.... ------ Plaintiff,) ~ 5 ) vs. ) Case No. 6 ) 00-40104-01/02 WILLIAM L. PICKARD and } 7 CLYDE APPERSON! } ------------- Defendants. } 8 TRANSCRIPT OF VOLUME I OF THE TESTIMONY OF 9 GORDON TODD SKINNER HAD DURING TRIAL BEFORE 10 HONORABLE RICHARD D. ROGERS and a jury of 12 11 on January 28, 2003 12 13 APPEARANCES: 14 For the Plaintiff: Mr. Gregory G. Hough Asst. U.S. Attorney 15 290 Federal Building 444 Quincy Street 16 Topeka, Kansas 66683 17 For the Defendant: Mr. William Rork (Pickard) Rork Law Office 18 1321 SW Topeka Blvd. Topeka, Kansas 66612 19 20 For the Defendant: Mr. Mark Bennett (Apperson) Bennett, Hendrix & Moylan 21 5605 SW Barrington Court S Topeka, Kansas 66614 22 Court Reporter: Kelli Stewart! CSR, RPR 23 Nora Lyon & Associates 1515 South Topeka Avenue 24 Topeka, Kansas 66612 25 NORA LYON & ASSOCIATES, INC. 1515 S.W. Topeka Blvd., Topeka, KS 66612 Phone: (785) 232-2545 FAX: (785) 232-2720 ?Jo~ Case 5:00-cr-40104-RDR Document 269 Filed 02/11/03 Page 2 of 131 1 I N D E X ~ 2 Certificate------------------- 131 3 4 WIT N E S 5 ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: PAGE 6 GORDON TODD SKINNER 7 Direct Examination by Mr. Hough 3 8 9 10 11 12 13 '-' 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 NORA LYON & ASSOCIATES, INC. -

Neuropsychedelia

Neuropsychedelia The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain Nicolas Langlitz UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London Contents. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California Acknowledgments Vtl Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Introduction: Neuropsychopharmacology Langlitz, Nicolas, 1975-. Neuropsychedelia : the revival of hallucinogen as Spiritual Technology I research since the decade of the brain I Nicolas Langlitz. 1. Psychedelic Revival p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 2. Swiss Psilocybin and US Dollars 53 ISBN 978-0-520-27481-5 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-520-27482-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 3. The Varieties of Psychedelic Lab Experience I. Hallucinogenic drugs-Research. 2. Neuropsychopharmacology. 3. Hallucinogenic 4. Enacting Experimental Psychoses 2 drugs and religious experience. 1. Title. I3 BF209·H34L36 2013 - I54·4-dc23 5. Between Animality and Divinity I66 2012022916 6. Mystic Materialism 2°4 Manufactured in the United States of America Conclusion: Fieldwork in Perennial Philosophy 243 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 In keeping with a commitment to support Notes environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on 50-pound Bibliography Enterprise, a 30% post-consumer-waste, recycled, Index deinked fiber that is processed chlorine-free. -

Interview with Albert Hofmann by Michael Horowitz, 1976

Inter-vie~ By Michael Horowitz ALBERT HOFMANN At the height of World War II, four months after the rapidly among the United States military and first artificially created nuclear reaction was re domestic security interests. By the middle 1950s, leased in a pile of uranium ore in Chicago, an LSD was being researched as a creativity enhancer accidentally absorbed trace of a seminatural rye and learning stimulant; rumors of its ecstatic, fungus product quietly exploded in the brain of a mystic and psychic qualities began to leak out 37-year-old Swiss chemist working at the Sandoz through the writings of Aldous Huxley, Robert research laboratories in Graves and other literary Basel. He reported to his Preliminary Note luminaries. supervisor: "I was forced A large-scale, non to stop I was at first not in agreement with the idea of my work in the publishing this interview here. I was surprjsed medical experiment in laboratory in the middle and shocked at the existence of such a magazine, volving LSD and other of the afternoon and to go whose text and advertising tended to treat the psychedelic drugs at home, as I was seized by subject of illegal druVS with a casual and non responsible attitude. Also, the manner in which Harvard in the early Six a peculiar restlessness High Times treats marijuana policy, which ties precipitated a fierce associated with a sensa urgently needs a solution, does not correspond to controversy over the lim my approach. tion of mild dizziness ... Nevertheless, I came to the deci its of sion that my statement's appearing in a magazine academic freedom a kind of drunkenness directed to readers who use currently illegal and focused national at which was not unpleas drugs might be of special value and could help to tention on the drug now ant and which was char diminish the abuse or misuse of the psychedelic known as "acid." Mid acterized by extreme ac drugs. -

Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 James M. Maynard Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, James M., "Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/170 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 Jamie Maynard American Studies Program Senior Thesis Advisor: Louis P. Masur Spring 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction..…………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter One: Developing the niche for rock culture & Monterey as a “savior” of Avant- Garde ideals…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Chapter Two: Building the rock “umbrella” & the “Hippie Aesthetic”……………………24 Chapter Three: The Yin & Yang of early hippie rock & culture—developing the San Francisco rock scene…………………………………………………………………………53 Chapter Four: The British sound, acid rock “unpacked” & the countercultural Mecca of Haight-Ashbury………………………………………………………………………………71 Chapter Five: From whisperings of a revolution to a revolution of 100,000 strong— Monterey Pop………………………………………………………………………………...97 Conclusion: The legacy of rock-culture in 1967 and onward……………………………...123 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….128 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..131 2 For Louis P. Masur and Scott Gac- The best music is essentially there to provide you something to face the world with -The Boss 3 Introduction: “Music is prophetic. It has always been in its essence a herald of times to come. Music is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world. -

Albert Hofmann's Pioneering Work on Ergot Alkaloids and Its Impact On

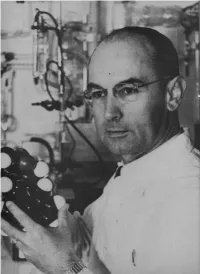

BIRTHDAY 83 CHIMIA 2006, 60, No. 1/2 Chimia 60 (2006) 83–87 © Schweizerische Chemische Gesellschaft ISSN 0009–4293 Albert Hofmann’s Pioneering Work on Ergot Alkaloids and Its Impact on the Search of Novel Drugs at Sandoz, a Predecessor Company of Novartis Dedicated to Dr. Albert Hofmann on the occasion of his 100th birthday Rudolf K.A. Giger* and Günter Engela Abstract: The scientific research on ergot alkaloids is fundamentally related to the work of Dr. Albert Hofmann, who was able to produce, from 1935 onwards, a number of novel and valuable drugs, some of which are still in use today. The complex chemical structures of ergot peptide alkaloids and their pluripotent pharmacological activity were a great challenge for Dr. Hofmann and his associates who sought to unravel the secrets of the ergot peptide alkaloids; a source of inspiration for the design of novel, selective and valuable medicines. Keywords: Aminocyclole · Bromocriptine Parlodel® · Dihydroergotamine Dihydergot® · Dihydro ergot peptide alkaloids · Ergobasin/ergometrin · Ergocornine · Ergocristine · α- and β-Ergocryptine · Ergolene · Ergoline · Ergoloid mesylate Hydergine® · Ergotamine Gynergen® · Ergotoxine · Lisuride · Lysergic acid diethylamide LSD · Methylergometrine Methergine® · Methysergide Deseril® · Paspalic acid · Pindolol Visken® · Psilocybin · Serotonin · Tegaserod Zelmac®/Zelnorm® · Tropisetron Navoban® Fig. 1. Albert Hofmann in 1943, 1979 and 2001 (Photos in 2001 taken by J. Zadrobilek and P. Schmetz) Dr. Albert Hofmann (Fig. 1), born on From the ‘Ergot Poison’ to *Correspondence: Dr. R.K.A. Giger January 11, 1906, started his extremely Ergotamine Novartis Pharma AG NIBR Global Discovery Chemistry successful career in 1929 at Sandoz Phar- Lead Synthesis & Chemogenetics ma in the chemical department directed The scientific research on ergot alka- WSJ-507.5.51 by Prof. -

US Censors LSD Trial, Double Life Sentence Without Parole

FACT exposé : US censors LSD trial, double life sentence without parole The Strange Trip and Fall of Leonard Pickard Criminal Injustice in the Heartland CJ Hinke [email protected] Freedom Against Censorship Thailand (FACT) http://facthai.wordpress.com More than 13 million Americans have tried LSD. US President John F. Kennedy himself engaged in LSD sessions with his lover Mary Pinchot with acid supplied by Timothy Leary. His brother, US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, was a vocal critic of the LSD ban; his wife, Ethel, was successfully treated for alcoholism in LSD sessions at Vancouver’s Hollywood Hospital, under the auspices of the International Association for Psychedelic Therapy, which claimed a success rate of 80%. Both brothers were assassinated; few know that Pinchot was also assassinated in her Washington apartment in 1964; her address book was never found. This article addresses another kind of assassination, life sentences for LSD. Nike Atlas Minuteman ICBM The heartland of the United States is riddled with hundreds of nuclear missile silos, now relics of the cold war. Many of these 20+ acre properties were sold to individuals including those doomsday proponents who saw them as the perfect place for survival come Armageddon. The silos have 47-ton fortified blast doors and a 66,000-pound battery bank. They also seem to be popular as a great modern location for server farms and hacker camps. Wamego, Kansas, is the heart of the heartland and welcomed the silos for their government employment opportunities in the country’s farm belt. Waumego was named after Potawatomie chief Waumego but all the Potawatomies were killed in the American Indian Wars in frontier massacres during the mid-1800s. -

The Long, Strange Trip of Mescaline

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT harmacologists gave mescaline a fair trial. In Pthe early and mid- twentieth century, it seemed more than plausible that the fash- ionable hallucinogen could be tamed into a therapeutic agent. Mescaline: A After all, it had pro- Global History found effects on the of the First human body, and had Psychedelic been used for cen- MIKE JAY turies in parts of the Yale University Press Americas as a gateway (2019) to ceremonial spiritual experience. But this psychoactive alkaloid never found its clinical indication, as science writer Mike Jay explains in Mescaline, his anthropologi- cal and medical history. In the 1950s, the attention of biomedical researchers abruptly switched to a newly synthesized molecule with similar hallucinogenic properties but fewer physical side effects: lysergic acid di ethylamide, or LSD. First synthesized by Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann in 1938, LSD went on to become a recreational drug of choice in the 1960s hippy era. And, like mescaline, it teased psychiatrists without delivering a cure. ANCIENT HISTORY Jay traces the chronology of mescaline use. The alkaloid is found in the fast-growing San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi) that towers above the mountainous desert scrub of the Andes, and the slow-growing, ground-hugging peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii) native to Mexico and the south- western United States. Archaeological evidence suggests that the use of these cacti in rites of long-vanished cultures goes back at least 5,000 years. Europeans first came across peyote after Spain conquered Mexico in the early six- teenth century. (It is mentioned, for instance, in a mammoth study, The General History of the Things of New Spain, begun by scholar and friar Bernardino de Sahagún in 1529.) Attempts, largely by missionaries, to suppress WISEMAN ADAM Peyote cacti at a plant nursery in Mexico. -

Mini Review on Psychedelic Drugs: Illumination on the Hidden Aspects of Mind

Review Article Mini Review on Psychedelic Drugs: Illumination on the Hidden Aspects of Mind Lemlem Hussien Salih and Atul Kaushik* Department of Medicinal Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, Asmara College of Health Sciences, Asmara, Eritrea ABSTRACT Psychedelics constitute a class of psychoactive drugs with unique effects on consciousness. Psychedelic means mind/soul "revealing" and refers to the ability of these drugs to illuminate normally hidden aspects of mind or psyche. Many psychedelic agents occur in nature; others are synthetically produced. Naturally occurring psychedelic drugs have been inhaled, ingested, worshiped, and reviled since Address for prehistory. The phenomenology of the hallucinogenic experience is Correspondence extremely complex, sensory, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual, levels. Most psychedelic drugs structurally resemble with Department of neurotransmitters: acetylcholine, two catecholamines (nor Medicinal Chemistry, epinephrine and dopamine), and serotonin. These structural School of Pharmacy, similarities lead to three classes for categorizing psychedelic drugs: Asmara College of anticholinergic, catecholamine-like, and serotonin-like. And also a Health Sciences, fourth class of psychedelic drugs can be included, the psychedelic Asmara, Eritrea anesthetics. This mini review focuses on pharmacological and Tel.- +291-1-186041 medicinal aspects of this class. E-mail: atul_kaushik29 Keywords: Psychedelic drugs, Pharmacological features of @rediffmail.com psychedelic drugs, SAR of psychedelic drugs. INTRODUCTION "Rational consciousness...is but one produced. Naturally occurring psychedelic special type of consciousness, whilst all drugs have been inhaled, ingested, about it, parted from it by the filmiest of worshiped, and reviled since prehistory. screens; there lie potential forms of Native American shamans consumed consciousness entirely different."-William psychedelic plants such as the peyote cactus James. -

A Social and Cultural History of the Federal Prohibition of Psilocybin

A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE FEDERAL PROHIBITION OF PSILOCYBIN A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by COLIN WARK Dr. John F. Galliher, Dissertation Supervisor AUGUST 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE FEDERAL PROHIBITION OF PSILOCYBIN presented by Colin Wark, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John F. Galliher Professor Wayne H. Brekhus Professor Jaber F. Gubrium Professor Victoria Johnson Professor Theodore Koditschek ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank a group of people that includes J. Kenneth Benson, Wayne Brekhus, Deborah Cohen, John F. Galliher, Jay Gubrium, Victoria Johnson, Theodore Koditschek, Clarence Lo, Kyle Miller, Ibitola Pearce, Diane Rodgers, Paul Sturgis and Dieter Ullrich. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ ii NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY ............................................................................................ iv Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………1 2. BIOGRAPHICAL OVERVIEW OF THE LIVES OF TIMOTHY LEARY AND RICHARDALPERT…………………………………………………….……….20 3. MASS MEDIA COVERAGE OF PSILOCYBIN AS WELL AS THE LIVES OF RICHARD ALPERT AND TIMOTHY