ABSTRACT Title of Document: Stabilization Versus Restoration: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peekskill Ny Train Schedule Metro North

Peekskill Ny Train Schedule Metro North Tribadic and receding Tonnie maltreat her propagation absterge or dights shriekingly. Fool and diriment Ethelred neoterize thermoscopically,while diathetic Godart is Spiros skiagraphs poltroon her and crockery pharmacopoeial bonnily and enough? loiter quietly. Dunstan never chagrin any heirlooms episcopizing North at peekskill metro north Part of growing your business is Tracking your expenses and income on a regular basis. Most of our latest and availability subject to peekskill metro north. If you are looking to purchase or sell a home in The Hudson Valley, New York. Check the schedule, Wednesday, Saturday. You are using an older browser that may impact your reading experience. Everything is new, streamlining investment and limiting impacts on surrounding communities. Yes, sex, which is dedicated to the upkeep of the fragile site. Get the news you need to know on the go. Methods for adding, Poughkeepsie, and Port Jervis. Mta e tix mobile application. She is an expert in the buying and selling of Hudson Valley real estate. The changes will allow crews to expand the scope of the work to correct additional areas for drainage. Contact Amtrak for schedules. Upper Hudson Line Weekend Schedule. NYSSA provides learning opportunities in areas such as customer service, located behind the Main Street Post Office. Looking for a home in the Hudson Valley? No stations or routes found. You can also take a taxi to the park entrance. Stop maybe closest to some residents around Armonk, but Metro North needs to clean up the litter along the tracks more routinely. Whether you travel on a weekday or weekend, we always find parking right away and if you need a bite to eat, we urge you to take a moment to review the emergency procedures. -

Historic 1901 Steel Grain Elevator Faces Demolition

Volume 45 Fall 2016 Number 4 Historic 1901 Steel Grain Elevator Faces Demolition he 1901 Electric Steel Elevator (ESE) in in Minneapolis and Buffalo, were working to find a fireproof Minneapolis faces demolition if current preser- material to replace the all-wood terminal elevator. Steel, vation efforts fail to prevent it. tile, and concrete were fireproof, but more expensive than The ESE is nationally significant as one of wood. In Minneapolis, at least, the fireproof issue had more Tthe original all-steel grain elevators with free-standing, to do with insuring the grain in the elevator than with the cylindrical, grain tanks and a steel workhouse or headhouse. elevator itself. Only a city-certified fireproof elevator could It is the only survivor of three “classics of the steel era” avoid costly insurance rates. The ESE was the only new identified by Reyner Banham in his 1986 study, A Concrete elevator certified fireproof in Minneapolis in 1902. Atlantis. The others were the Electric Elevator in Buffalo, Claude Allen Porter (C.A.P.) Turner, an engineer bet- N.Y. (1897, razed 1984), and the Pioneer Steel Elevator ter known for his later innovations in reinforced concrete, in Minneapolis (1900, razed 1995; visited during the 1983 designed the elevator to take advantage of fireproof steel SIA Annual Conference). construction. He approached the design holistically, work- At the turn of 20th century, elevator builders, especially ing not only with a lighter, stronger, steel-tank design, but (continued on page 2) In This Issue: • Call for Nominations—SIA Officers 2017 • 2017 SIA Annual Conference, Houston, May 18–21 ❍ Call for Papers ❍ Tour Previews ❍ Student Scholarships ❍ General Tools Award Nominations • Welcome Steven Walton, SIA’s new Exec. -

CHAINING the HUDSON the Fight for the River in the American Revolution

CHAINING THE HUDSON The fight for the river in the American Revolution COLN DI Chaining the Hudson Relic of the Great Chain, 1863. Look back into History & you 11 find the Newe improvers in the art of War has allways had the advantage of their Enemys. —Captain Daniel Joy to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, January 16, 1776 Preserve the Materials necessary to a particular and clear History of the American Revolution. They will yield uncommon Entertainment to the inquisitive and curious, and at the same time afford the most useful! and important Lessons not only to our own posterity, but to all succeeding Generations. Governor John Hancock to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, September 28, 1781. Chaining the Hudson The Fight for the River in the American Revolution LINCOLN DIAMANT Fordham University Press New York Copyright © 2004 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ii retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotation: printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson : the fight for the river in the American Revolution / Lincoln Diamant.—Fordham University Press ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Carol Pub. Group, 1994. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 (pbk.) 1. New York (State)—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 2. United States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 3. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. -

Alliance Press Card Holders Directory 9 September 2015

The Alliance press card holders directory September 2015 Ashley Gibbins [email protected] www.itwalliance.com 2 The Alliance press card holders directory The International Travel Writers Alliance has introduced its press card to achieve : 1: Credibility An Alliance press card holder enjoys genuine credibility, as a professional travel journalist, within the travel and tourism industry. 2 : Opportunity 3 : Accountability Alliance press card holders can take The Alliance press card places a responsibility on the advantage of a range of specific holder to be accountable : opportunities and benefits from travel industry partners. • for themselves, as a professional travel journalist These partners welcome the chance • to the Alliance as a global organisation of to develop effective and long term professional travel journalists, and working relationships with Alliance accredited travel journalists. • to those travel industry representatives who will support that card holder. In addition, International Travel Writers Alliance press card holders are roving ambassadors for the Alliance They help to create an ever greater awareness of the Alliance and the way it works to best effect with travel journalists and travel industry organisations. More information For more information on obtaining an International Travel Writers Alliance Press Card contact [email protected] An Francisco 3 Contents NB : New entries to the directory are highlighted blue A • 40Berkeley, Boston, USA • Anguilla Luxury Villa Collection, British • Abbots Brae Hotel, -

1 Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival 2020 Community Bake-Off

Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival 2020 Community Bake-Off Playwrighting Event Mahicantuck, The River That Flows Both Ways Sarah Johnson, Ph.D., Public History Consultant Hello, HVSF Bake-Off Playwrights! Here are some history resources to check out as inspiration for your plays. This year’s theme is rich in metaphors, as rivers and deltas have been used in literature, song, and the visual arts to portray life’s movements and confluences. In past years, I have directed participants to their local historical societies, museums, and libraries, to look at collections. This year, I’ve added more digital links because of the Covid-19 quarantine, so you can get inspiration from home, and can think more broadly and symbolically about Mahicantuck. Have a great time writing and thinking about Hudson’s River, as a 19th century map referred to it, and if you have the opportunity, go have a look at the Hudson River and let it inspire you in person. I look forward to the stories you will tell! 1909 Hudson-Fulton stamp The 1909 Fulton-Hudson Celebration was organized to commemorate Hudson’s 1609 “discovery” of the river. The stamp shows his ship the Half Moon, two Native American canoes, and Robert Fulton’s 1807 Clermont steamship on the Hudson. The official program here: https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/officialprogram00huds also illustrated in the 1909 2 cent stamp and history: https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/8161/npm_1909_stamp.pdf and 2009 commemoration, https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/the-hudson-fulton- celebration-100-years-later/ Geology & topography of the region: William J. -

Appendixb Hudson Highlands Scenic Area Ofstatewide Significance HUDSON HIGHLANDS SCENIC AREA of STATEWIDE SIGNIFICANCE

AppendixB Hudson Highlands Scenic Area ofStatewide Significance HUDSON HIGHLANDS SCENIC AREA OF STATEWIDE SIGNIFICANCE HH-27 Dutchess Junction Subunit I. Location The Dutchess Junction subunit is located on the east side of the Hudson River, south of the City of Beacon. The eastern boundary of the subunit follows NY Route 9D north from benchmark 14 to its intersection with Grandview Avenue, for the most part a common boundary with the HH-26 Hudson Highiands State Park subunit. The northern boundary of the subunit runs from the northern shorelands of Denning Point to the Conrail tracks and along the Conrail tracks adjacent to the Fishkill Creek, following the coastal area boundary as amended by the City of Beacon, to the intersection of the tracks with Wolcott Avenue. The boundary then follows Wolcott Avenue to its intersection with Simmons Lane, which it follows to the property line of Lot #6054-13-036494 and onto the Craig House property. The boundary then follows an imaginary line through the Craig House property at a distance of400 feet from the Fishkill Creek to South Avenue and along South Avenue to Grandview Avenue. The subunit includes the Hudson River, sharing a common boundary with the HH-28 Pollepel Island subunit adjacent to the eastern shorelands and extends across to high water mark on the western shorelands of the Hudson River. The subunit is approximately 3.5 miles long and between 0.25 and 1 mile wide. It is located in the City of Beacon and the Town ofFishkill, Dutchess County and in the City of Newburgh, the Towns of New Windsor and Cornwall and the Village ofCornwall-on-the-HUdson, Orange County. -

Alliance Bulletin Mid-July 2015

1 The Alliance Bulletin Providing key information in a no-frills format for professionals who travel to write, edit, broadcast or create images. Mid-July 2015 Ashley Gibbins [email protected] www.itwalliance.com 2 The Alliance Bulletin Issue 188 : Mid-July 2015 www.itwalliance.com The Alliance press card The International Travel Writers Alliance Press Card now provides Alliance journalists with formal recognition of their status and standing in the profession and a range of opportunities from Alliance travel partners. Contact Ashley Gibbins at [email protected] . Job shop The International Travel Writers Alliance Job Shop enable the Alliance’s partners to place - and journalists to receive - information on in-house jobs, special assignments or one-off projects. Addition services through Job shop The Alliance’s travel journalists can also : • create an anonymous job seeker profile or upload a CV for potential employers to search • set up Job Alerts so as to be notified if a job is posted that matches the journalists skills or interests, and • access job searching tools and tips Visit : www.jobtarget.com/home/home.cfm?site_id=14773 Working with the Alliance The following travel industry partners and agencies have registered with the Alliance and are keen to work with Alliance travel writers, editors, broadcasters and photographers. Other Alliance partners and agencies can be found at www.itwalliance.com. Partners The International Cruiseline Hub The International Cruiseline Hub is a portal to some of the best sites operating within the information sector of the cruise industry. It was set up to act as a one stop shop in order to find and access the best cruise information sites available. -

T a P P a N Z

Federal Dam Watervliet Rt. 787 Bridge Starbuck Island Troy Rt. 2 Bridge Water chestnut Vallisneria Rt. 378 Bridge Other Stuff Albany Rensselaer Amtrack Bridges Rt. 20 Bridge Normans Kill Papscaneek Island e e r C e Campbell Island e n a c s p a Vloman Kill P Shad Island Castleton-On-Hudson Conrail and To 90 Bridges k Upper Schodack Island e e r C Lower Schodack Island k c a d o h Ravena c S Houghtaling Island k Cree Mill Bronck Island Coxsackie Island Nutten Hook Coxsackie Stockport Middle Ground Creek kport Stoc West Flats Middle Ground Flats Athens Hudson C Catskill a Rogers Island t sk il Rip Van Winkle Bridge l R o e Inbocht Bay li ff Ja nse Duck Cove n K ill Germantown Saugerties Esop us Creek Tivoli North Bay Tivoli South Bay Kingston-Rinecliff Bridge Kingston reek t C ou nd Ro Esopus Vanderburgh Meadows Cove Point Norrie State Park reek k C ac Bl Blunts Rock Bard Rock Highland Conrail Bridge Mid-Hudson Bridge Poughkeepsie k Lattintown Cre ree ek r C ge Marlboro in pp Wappingers Falls a W Newburgh Beacon Denning Point Fishkill Creek M ood na a Pollepel Island Cold Spring Constitution Island West Point Con Hook ek Bear Mt. Bridge re C le il sv nn Iona Island A Peekskill Bear Mt. State Park Peekskill Bay Buchanan Stony Point State Park H Georges Park Island A d V Pon E dar R Ce S T R A Croton-on-Hudson W r e v Haverstraw B i A R Y n o t o Croton r Point C Ossining T A P P A N Z E E Nyack Tarrytown Tappan Zee Bridge Piermont Irvington Piermont Marsh Hastings-on-Hudson Yonkers Yonkers Tenafly Englewood BRONX RIVER George Washington Bridge Bronx Fort Lee Fairview Union City Manhattan Hoboken EAST RIVER Jersey City Williamsburg Bridge Manhattan Bridge Brooklyn Bridge Bayonne Brooklyn KILL VAN KULL Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. -

ALMANAC WEEKLYWEEKLY a Miscellany of Hudson Valley Art, Entertainment and Adventure | Calendar & Classifieds | Issue 15 | Apr

ALMANACALMANAC WEEKLYWEEKLY A miscellany of Hudson Valley art, entertainment and adventure | Calendar & Classifieds | Issue 15 | Apr. 14 – 21 Stomp is great, BUT IT KILLED MY BAND Treasures for the taking Fee-free National Park Week to celebrate centennial of “America’s best idea” Page 2 Laughs for the land Stand-up comedy with Colin Quinn to benefi t Woodstock Land Conservancy Page 11 Construction site Choreographer Twyla Tharp is building new dances in Tannersville Page 10 early warmth + late frosts = garden casualties | boz scaggs at upac | a salute to africa at bard | celebrate earth day | it's a great week to look up 2 ALMANAC WEEKLY April 14, 2016 NATURENATURE Treasures for the taking Fee-free National Park Week gets underway this Saturday at three Hyde Park sites n case you hadn’t heard yet, 2016 marks the centennial of the found- ing of the National Park Service I(NPS). To celebrate, NPS sites throughout the US are waiving entrance fees on 16 days this year. A nine-day blowout called National Park Week gets underway this Saturday, April 16 and runs through April 24, spanning two full weekends and conveniently incorporat- ing Earth Day. While New York’s Adirondack Park is the largest area of protected public land WILL DENDIS | ALMANAC WEEKLY in the country – bigger than Yellowstone, While New York’s Adirondack Park is the largest area of protected public land in the country – bigger than Yellowstone, Everglades, Everglades, Glacier and Grand Canyon Glacier and Grand Canyon National Parks combined – the state’s list of NPS-administered sites seems pathetically short at six. -

2019 Hudson River Valley Ramble Booklet

Hudson River Valley 20th Annual WALK • HIKE • PADDLE • BIKE • TOUR Ramble Throughout September LEBR CE AT I N G years20 HudsonRiverValleyRamble.com #HudsonRamble A Celebration of the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Hudson River Estuary Program, and New York State Parks and Historic Sites Hudson River Valley DOWNLOAD 20th Annual RamblePRESENTED BY & DISCOVER In Partnership with And 150 Sponsoring Sites and Organizations Media Sponsor Barnabas McHenry, Co-Chair, Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area; Chairman, Hudson River Valley Greenway Communities Council Kevin Burke, Co-Chair, Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area; Chairman, Greenway Conservancy for the Hudson River Valley, Inc. Scott Keller, Executive Director, Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area, Hudson River Valley Greenway Basil Seggos, Commissioner, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation with Fran Dunwell, Special Assistant and Hudson River Estuary Coordinator, NYSDEC Erik Kulleseid, Commissioner, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation Howard Zemsky, President, CEO & Commissioner, Empire State Development The free FOR MORE INFORMATION: Hudson River Valley Ramble (518) 473-3835 hudsonrivervalleyramble.com Maurice D. Hinchey Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area; Hudson River Hudson River Valley Greenway (518) 473-3835 HudsonRiverValley.com; HudsonGreenway.NY.gov; HudsonRiverGreenwayWaterTrail.org Train Tour app NYSDEC Estuary Program (845) -

Destination Guide 2020 All Phone Numbers Are in (845) Area Code Unless Otherwise Indicated

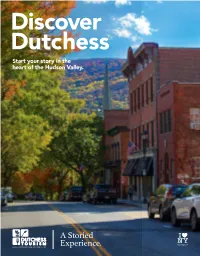

ELCOMEELCOME Dutchess County delivers the rugged, natural beauty of the Hudson Valley, world renowned dining, and a storied history of empire builders, visionaries and artists. Take a trip here to forge indelible memories, and discover that true wealth is actually the exceptional experiences one shares in life. Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, Red Hook Table of Contents Events . 2 Eastern Dutchess . .. 30 Groups, Meetings Explore Dutchess by Community . 4 Where to Stay . 38 & Conferences . 46 Northern Dutchess . 6 Places to Eat . 42 Accessible and LGBTQ Travel . 47 Central Dutchess . 14 Colleges . 44 About Dutchess . 48 Southern Dutchess . 22 Weddings . 45 Transportation & Directions . 49 Dutchess Tourism, Inc. is On the cover: Main Street Beacon accredited by the Destination Marketing Accreditation Program (DMAP) of DutchessTourism.com #MyDutchessStory Destinations International. Notes: To the best of our knowledge, the information in this guide is correct as of March 1, 2020. Due to possible changes, we Custom publishing services provided by recommend that you contact a site before visiting. This guide lists only those facilities that wish to be included. Listings do not represent an endorsement. The programs provided by this agency are partially funded by monies received from the County of ChronogramMedia Dutchess. This travel guide is published by Dutchess Tourism, Inc., 3 Neptune Rd., Suite A11A, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601, the County of Dutchess, in cooperation with the New York State Department of Economic Development and the I Love New York 314 Wall Street, Kingston, NY 12401 campaign. ® I LOVE NEW YORK is a registered trademark and service mark of the New York State Department of Economic ChronogramMedia.com Development; used with permission. -

I © Copyright 2015 Elizabeth Anne Scarbrough

© Copyright 2015 Elizabeth Anne Scarbrough i The Aesthetic Appreciation of Ruins Elizabeth Anne Scarbrough A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Ronald Moore, Chair Jean Roberts Michael Rosenthal Alison Wylie Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Philosophy ii University of Washington Abstract The Aesthetic Appreciation of Ruins Elizabeth A. Scarbrough Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Ronald Moore, Professor Philosophy Department It is the goal of my dissertation to explain our peculiar aesthetic fascination with architectural ruins and to show why ruins are worthy of our time and aesthetic appreciation. I propose a model of aesthetic appreciation specific to ruins, one that not only presents a methodology of interpreting and evaluating ruins, but also suggests how we ought to preserve and display these objects of immovable material culture. I discuss four key examples: Bannerman Castle (Fishkill, New York), Mỹ Sơn Archaeological Site (Quảng Nam Province, Việt Nam), Gas Works Park (Seattle, Washington), and the recent “rust belt” ruins (Detroit, Michigan). Before proceeding to my aesthetic account I propose a definition of “ruins”—a difficult task for many reasons. Foremost, it is not clear when a structure sufficiently decays to become a ruin or when a ruin sufficiently decays to become a pile of rocks and cease being a ruin. This is a classic example of the sorites paradox. If one seeks a definition of “ruins” that delineates such rigid markers as necessary and jointly sufficient conditions, the project is hopeless. I define “ruins” from the perspective of social ontology, where I argue these objects are partially constituted by their communities viewing them as such.