Johannes Baader's Postwar Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Text and the Coming of Age of the Avant-Garde in Germany

The Text and the Coming of Age of the Avant-Garde in Germany Timothy 0. Benson Visible Language XXI 3/4 365-411 The radical change in the appearance of the text which oc © 1988 Visible Language curred in German artists' publications during the teens c/o Rhode Island School of Design demonstrates a coming of age of the avant-garde, a transfor Providence, RI 02903 mation in the way the avant-garde viewed itself and its role Timothy 0. Benson within the broader culture. Traditionally, the instrumental Robert Gore Riskind Center for purpose of the text had been to interpret an "aesthetic" ac German Expressionist Studies tivity and convey the historical intentions and meaning as Los Angeles County Museum ofArt sociated with that activity. The prerogative of artists as 5905 Wilshire Boulevard well as critics, apologists and historians, the text attempted Los Angeles, CA 90036 to reach an observer believed to be "situated" in a shared web of events, thus enacting the historicist myth based on the rationalist notion of causality which underlies the avant garde. By the onset of the twentieth century, however, both the rationalist basis and the utopian telos generally as sumed in the historicist myth were being increasingly chal lenged in the metaphors of a declining civilization, a dis solving self, and a disintegrating cosmos so much a part of the cultural pessimism of the symbolist era of "deca dence."1 By the mid-teens, many of the Expressionists had gone beyond the theme of an apocalypse to posit a catastro phe so deep as to void the whole notion of progressive so cial change.2 The aesthetic realm, as an arena of pure form and structure rather than material and temporal causality, became more than a natural haven for those artists and writers who persisted in yearning for such ideals as Total itiit; that sense of wholeness for the individual and human- 365 VISIBLE LANGUAGE XXI NUMBER 3/4 1987 *65. -

Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other 05.08.–07.11.2016

Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other 05.08.–07.11.2016 PRESS KIT Hannah Höch, Untitled (From an Ethnographic Museum), 1929 © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2016 CONTENTS Press release Education programme and project space “Dada is here!” Press images Exhibition architecture Catalogue National and international loans Companion booklet including the exhibition texts New design for Museum Shop WWW.BERLINISCHEGALERIE.DE BERLINISCHE GALERIE LANDESMUSEUM FÜR MODERNE ALTE JAKOBSTRASSE 124-128 FON +49 (0) 30 –789 02–600 KUNST, FOTOGRAFIE UND ARCHITEKTUR 10969 BERLIN FAX +49 (0) 30 –789 02–700 STIFTUNG ÖFFENTLICHEN RECHTS POSTFACH 610355 – 10926 BERLIN [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Ulrike Andres Head of Marketing and Communications Tel. +49 (0)30 789 02-829 [email protected] Contact: ARTEFAKT Kulturkonzepte Stefan Hirtz Tel. +49 (0)30 440 10 686 [email protected] Berlin, 3 August 2016 Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other 05.08.–07.11.2016 Press conference: 03.08.2016, 11 am, opening: 04.08.2016, 7 pm Dada is 100 years old. The Dadaists and their artistic articulations were a significant influence on 20th-century art. Marking this centenary, the exhibition “Dada Africa. Dialogue with the Other” is the first to explore Dadaist responses to non- European cultures and their art. It shows how frequently the Dadaists referenced non-Western forms of expression in order to strike out in new directions. The springboard for this centenary project was Dada’s very first exhibition at Han Coray’s gallery in Zurich. It was called “Dada. Cubistes. Art Nègre”, and back in Hannah Höch, Untitled (From an 1917 it displayed works of avant-garde and African art side by Ethnographic Museum), 1929 side. -

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection... Page 1 of 26 Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection IRENE E. HOFMANN Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago Dada 6 (Bulletin The Mary Reynolds Collection, which entered The Art Institute of Dada), Chicago in 1951, contains, in addition to a rich array of books, art, and ed. Tristan Tzara ESSAYS (Paris, February her own extraordinary bindings, a remarkable group of periodicals and 1920), cover. journals. As a member of so many of the artistic and literary circles View Works of Art Book Bindings by publishing periodicals, Reynolds was in a position to receive many Mary Reynolds journals during her life in Paris. The collection in the Art Institute Finding Aid/ includes over four hundred issues, with many complete runs of journals Search Collection represented. From architectural journals to radical literary reviews, this Related Websites selection of periodicals constitutes a revealing document of European Art Institute of artistic and literary life in the years spanning the two world wars. Chicago Home In the early part of the twentieth century, literary and artistic reviews were the primary means by which the creative community exchanged ideas and remained in communication. The journal was a vehicle for promoting emerging styles, establishing new theories, and creating a context for understanding new visual forms. These reviews played a pivotal role in forming the spirit and identity of movements such as Dada and Surrealism and served to spread their messages throughout Europe and the United States. -

The False Gods of Dada

The false Gods of Dada: on Dada Presentism by Maria Stavrinaki A new book on the movement draws lessons on the dangers of eclecticism by Pac Pobric | 13 May 2016 | The Art Newspaper Artists at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin, June 1920. In the final chapter of the art historian Maria Stavrinaki's new book, Dada Presentism, she imagines the origin of Dada as an immaculate conception. "Who, in fact, did invent Dada?" she asks. "Everyone and no one." Amidst the devastation of the First World War, with Enlightenment optimism in ruin, Dada arrived as a miraculous redeemer. Stavrinaki echoes the German Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck, who wrote in his 1920 history of the movement that "Dada came over the Dadaists without their knowing it; it was an immaculate conception, and thereby its profound meaning was revealed to me." Throughout her book, Stavrinaki hews closely to this clerical line, offering essentially theological claims about the movement. In the collages of Raoul Hausmann and the masks of Marcel Janco, Stavrinaki sees God-like reconciliation of all opposites. The Dadaists were both Futurists, with all the attendant utopian aspiration that implies, and Primitivists, insofar as they were fascinated by mythical history. "For those intellectuals and artists who found neither comfort in the past nor in the future, the only remaining choice was to gain a foothold in the present", Stavrinaki writes—a present characterised, above all, by its openness to all possibility. Dada's "presentism"—its absorption of all that had come and all that was to be— allowed for omniscience and absolute artistic opportunity. -

Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: the Avant-Garde, No

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/raoulhausmannberOOOObens Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 55 Stephen C. Foster, Series Editor Associate Professor of Art History University of Iowa Other Titles in This Series No. 47 Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s Jeanne Siegel No. 48 Dadaj Dimensions Stephen C. Foster, ed. No. 49 Arthur Dove: Nature as Symbol Sherrye Cohn No. 50 The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine Myroslava M. Mudrak No. 51 Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth- Century France Marilyn R. Brown No. 52 Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land William S. Bradley No. 53 The Skyscraper in American Art, 1890-1931 Merrill Schleier No. 54 Andy Warhol’s Art and Films Patrick S. Smith Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada by Timothy O. Benson T TA /f T Research U'lVlT Press Ann Arbor, Michigan \ u » V-*** \ C\ Xv»;s 7 ; Copyright © 1987, 1986 Timothy O. Benson All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an imprint of University Microfilms, Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Benson, Timothy O., 1950- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. (Studies in the fine arts. The Avant-garde ; no. 55) Revision of author’s thesis (Ph D.)— University of Iowa, 1985. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Aesthetics. 2. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Political and social views. -

De Stijl Presentation Cdul

Dadaism and De Stijl In Europe The Emergence of Dadism during WW1 and the Rebirth of Order with the De Stijl Design and the World in Transition: Before and after WW1 , new concepts and forms emerged in the form of art and design movements: 1. Art Nouveau 2. Expressionism 3. Futurism 5. Cubism Influencing these emergent trends were new ideas, technologies, materials and political and social change and upheaval. Seen as part of a desire to return to order, the De Stijl movement was a natural response to the chaos that corresponded with the events of WW1. The Emergence of Dadaism • Dadaism was a cultural movement that was concentrated on anti-war politics which then made its way to the art world through art theory, art manifestoes, literature, poetry and eventually graphic design and the visual arts. The movement, although Dadaists would not have been happy calling it a movement, originated in Switzerland and spread across Europe and into the United States, which was a safe haven for many writers during World War I. An anti-art movement, Dadaists attempted to break away from the styles of traditional art aesthetics as well as rationality, of any kind. They produced a great many publications as a home for their writings and protest materials which were handed out at gatherings and protests. The visual aesthetics associate with the movement often include found objects and materials combined through collage. Marcel Duchamp, Fountain 1917 Quite literally inverting Reality, a urinal upended and signed by Duchamp with the Name ‘Mott’, the plumbing supply chain that sold it to him. -

Dada Futures: Inflation, Speculation, and Uncertainty in Der Dada No

UC Berkeley TRANSIT Title Dada Futures: Inflation, Speculation, and Uncertainty in Der Dada No. 1 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4043n8kj Journal TRANSIT, 10(2) Author Beals, Kurt Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/T7102031160 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Beals: Dada Futures: Inflation, Speculation, and Uncertainty in Der Dada No. 1 Dada Futures: Inflation, Speculation, and Uncertainty in Der Dada No. 1 TRANSIT vol. 10, no. 2 Kurt Beals Introduction In June 1919, shortly before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the Berlin Dadaists Raoul Hausmann and Johannes Baader published the first issue of their magazine Der Dada.1 Although it comprised a mere eight pages, Der Dada No. 1 was hardly thin on ambition. Like the treaty itself, the magazine claimed to usher in a new era: Its first page proclaimed, “Die neue Zeit beginnt mit dem Todesjahr des Oberdada,” a reference to Baader, who had intentionally fed false rumors of his own demise to the German press (Fig. 1). From the very beginning, then, this magazine presented itself as a decisive break with the past, and heralded a radically different future. On subsequent pages, the magazine tackled topics ranging from politics to economics to religion, its tone veering from the polemical to the plainly satirical, punctuated by non-sequiturs, chaotic typography, and Hausmann’s rough-hewn woodcuts. One common thread amidst this diversity was a concern with the future, and above all with its manifest uncertainty. As the present article will demonstrate, such uncertainty gave rise to a distinctive attitude towards the future that can be recognized throughout the issue: an attitude of speculation. -

Francis Picabia's Anti-Art Anti-Christ

Jésus-Christ Rastaquouère: Francis Picabia’s Anti-Art Anti-Christ Sarah Hayden Jésus-Christ Rastaquouère was published in Paris in the autumn of 1920.1 After protracted, ultimately abortive, negotiations with René Hilsum and Bernard Grasset, it was produced at Francis Picabia’s own expense under the ‘Collection Dada’ imprint of Paris bookseller-publishers, Au Sans Pareil, and distributed by Jacques Povlovsky’s Librairie-Galerie La Cible.2 The fact that Ezra Pound was an early proponent of Picabia’s writing is not surprising; the fact that his enthusiastic early reading of Jésus-Christ Rastaquouère has not been succeeded by extensive further scholarship certainly is. Having dismissed Picabia in 1916 as a proponent of ‘modern froth’,3 by 1921 Pound was willing to praise his prowess ‘not exactly as a painter, but as a writer’.4 In the same year, Pound 1. Francis Picabia, Jésus-Christ Rastaquouère (Paris: Au Sans Pareil, 1920), hereafter JCR in the text. Translators and critics have offered various glosses on the book’s title. See Michel Sanouillet, Francis Picabia et 391, vol. 2 (Paris: Eric Losfeld, 1966), p. 123, and Francis Picabia, I am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose and Provocation, ed. and trans. by Marc Lowenthal (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2007), p. 223. Picabia also used the ‘rasta’ prefix in his visual art of this period, including Tableau rastadada (1920) (collage on paper, 19 x 17 cm), and Le Rastaquouère (1920). The latter of these was exhibited at the Salon d’automne, Paris, October 1920. For an illuminating treatment of the Tableau rastadada, see George Baker, ‘Long live Daddy’, October, 105 (2003), 37–72. -

Dada Was an Artistic and Literary Movement That Began in 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Dada was an artistic and literary movement that began in 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland. It arose as a reaction to World War I, and the nationalism, and rationalism, which many thought had brought war about. Influenced by ideas and innovations from several early avant-gardes - Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, and Expressionism - its output was wildly diverse, ranging from performance art to poetry, photography, sculpture, painting and collage. Dada's aesthetic, marked by its mockery of materialistic and nationalistic attitudes, proved a powerful influence on artists in many cities, including Berlin, Hanover, Paris, New York and Cologne, all of which generated their own groups. The movement is believed to have dissipated with the arrival Surrealism in France. Key Ideas / Information • Dada was born out of a pool of avant-garde painters, poets and filmmakers who flocked to neutral Switzerland before and during WWI. • The movement came into being at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in February 1916. The Cabaret was named after the eighteenth century French satirist, Voltaire, whose play Candide mocked the idiocies of his society. As Hugo Ball, one of the founders of Zurich Dada wrote, "This is our Candide against the times." • So intent were members of Dada on opposing all the norms of bourgeois culture, that the group was barely in favour of itself: "Dada is anti-Dada," they often cried. • Dada art varies so widely that it is hard to speak of a coherent style. It was powerfully influenced by Futurist and Expressionist concerns with technological advancement, yet artists like Hans Arp also introduced a preoccupation with chance and other painterly conventions. -

Readings: War Poetry and Dada

017_War-Poetry_Dada.doc READINGS: WAR POETRY AND DADA Background Various war poems Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front Background: Eugen Weber, Dada Tzara, Dada Manifesto Tzara, "Lecture on Dada" Interpretations of Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare… GROVEART.COM DADAISM Artistic and literary movement launched in Zurich in 1916 but shared by independent groups in New York, Berlin, Paris and elsewhere. The Dadaists channelled their revulsion at World War I into an indictment of the nationalist and materialist values that had brought it about. They were united not by a common style but by a rejection of conventions in art and thought, seeking through their unorthodox techniques, performances and provocations to shock society into self-awareness. The name Dada itself was typical of the movement’s anti- rationalism. Various members of the Zurich group are credited with the invention of the name; according to one account it was selected by the insertion of a knife into a dictionary, and was retained for its multilingual, childish and nonsensical connotations. The Zurich group was formed around the poets hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, tristan Tzara and richard Huelsenbeck, and the painters hans Arp, marcel Janco and hans Richter. The term was subsequently adopted in New York by the group that had formed around marcel Duchamp, francis Picabia, Marius de Zayas (1880–1961) and Man ray. The largest of several German groups was formed in Berlin by Huelsenbeck with john Heartfield, raoul Hausmann, hannah Höch and george Grosz. As well as important centres elsewhere (Barcelona, Cologne and Hannover), a prominent post-war Parisian group was promoted by Tzara, Picabia and andré Breton. -

Dada Comes to the Museum of Modern Art

DADA COMES TO THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART MoMA Installation Is a Dynamic Multimedia Display of Over 400 Works by Nearly 50 Artists from the Influential Avant-Garde Movement Dada June 18–September 11, 2006 The Joan and Preston Robert Tisch Gallery, sixth floor NEW YORK, June 13, 2006—Dada, on view at The Museum of Modern Art from June 18 to September 11, 2006, is the first major museum exhibition in the United States to focus exclusively on Dada, one of the most influential avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century. Responding to the disasters of World War I and to an emerging modern media and machine culture, Dada artists led a creative revolution that both boldly embraced and caustically criticized modernity itself. Pursuing innovative strategies of art making that included abstraction, chance procedures, collage, photomontage, readymades, performances, and media pranks, the Dadaists created an abiding legacy for the century to come. The exhibition features over 400 works in a dynamic multimedia display that includes films, paintings, photographs, printed matter, sound recordings, and objects. Among the nearly 50 artists represented are Hans Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Hans Richter, Kurt Schwitters, Sophie Taeuber, and Tristan Tzara. This exhibition surveys the many forms of Dada artistic production as developed in Berlin, Cologne, Hannover, New York, Paris, and Zurich, the six principal cities where Dada took hold between 1916 and 1924. It presents an expansive view of Dada, including Zurich’s experiments in radical abstraction, New York’s irreverent readymades and machine portraits, Berlin’s scathing political montages, Cologne’s hallucinatory imagery, Paris’s relentless critiques of painterly traditions, and Kurt Schwitters’s carefully composed recyclings of society’s detritus in Hannover. -

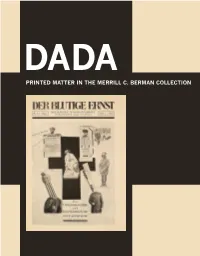

Dada: Printed Matter in the Merrill C. Berman Collection

DADA DADA PRINTED MATTER IN THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION PRINTED MATTE RIN THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION BERMAN C. MERRILL THE RIN MATTE PRINTED © 2018 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2018 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E 2018 M N A E R M R R I E L L B . C DADA PRINTED MATTER IN THE MERRILL C. BERMAN COLLECTION Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and notes by Adrian Sudhalter Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Images © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Der Blutige Ernst, year 1, no. 6 ([1920]) Issue editor: Carl Einstein Cover: George Grosz Letterpress on paper 12 1/2 x 9 1/2” (32 x 24 cm) CONTENTS 7 Headnote 10 1917 14 1918 18 1919 24 1920 48 1921 72 1922 78 1923 90 1924 96 1928 JOURNALS 104 1915-1916 291 126 1917 Neue Jugend 128 1917 The Blind Man 130 1917-1920 Dada 132 1917-1924 391 140 1918 Die Freie Strasse 146 1919 Jedermann sein eigener Fussball 148 1919-1920 Der Dada 152 1919-1924 Die Pleite 162 1919-1920 Der Blutige Ernst 168 1919-1920 Dada Quatsch 172 1920 Harakiri 176 1922-1923 Mécano 182 1922-1928 Manométre 184 1922 La Pomme de Pins 186 1922 La Coeur à Barbe 190 1923-1932 Merz Headnote Adrian Sudhalter Synthetic studies of Dada from the 1930s until today have tended to rely on a city-based cities was a point of pride among the Dadaists themselves: each new locale functioning as an outpost within Dada’s international network (see, for example, Tzara’s famous letterhead on p.