Medieval-Chapter.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

Helston & Wendron Messenger

Helston & Wendron Messenger October/November 2017 www.stmichaelschurchhelston.org.uk 1 2 THE PARISHES OF HELSTON & WENDRON Team Rector Canon David Miller, St Michael’s Rectory Church Lane, Helston, (572516) Email [email protected] Asst Priest Revd. Dorothy Noakes, 6 Tenderah Road, Helston (573239) Reader [Helston] Mrs. Betty Booker 6, Brook Close, Helston (562705) ST MICHAEL’S CHURCH, HELSTON Churchwardens Mr John Boase 11,Cross Street, Helston TR13 8NQ (01326 573200) A vacancy exists to fill the post of the 2nd warden since the retirement of Mr Peter Jewell Organist Mr Richard Berry Treasurer Mrs Nicola Boase 11 Cross Street, Helston TR13 8NQ 01326 573200 PCC Secretary Mrs Amanda Pyers ST WENDRONA’S CHURCH, WENDRON Churchwardens Mrs. Anne Veneear, 4 Tenderah Road, Helston (569328) Mr. Bevan Osborne, East Holme, Ashton, TR13 9DS (01736 762349) Organist Mrs. Anne Veneear, -as above. Treasurer Mr Bevan Osborne, - as above PCC Secretary Mrs. Henrietta Sandford, Trelubbas Cottage, Lowertown, Helston TR13 0BU (565297) ********************************************* Clergy Rest Days; Revd. David Miller Friday Revd. Dorothy Noakes Thursday Betty Booker Friday (Please try to respect this) 3 The Rectory, Church Lane Helston October/November 2017 Dear Everyone, Wendron Church has been awarded a grant to repair the medieval church of Wendron. At the moment we are at the preliminary stage and we have been given an initial grant for us and our firm of chartered surveyors to do the foundational work, necessary when drawing up specifications to send to potential contractors who can submit estimates and tenders based on the specification. There is much work to be done to slopes of the roof and tower, to the walls of the building and to the floor. -

English Heritage Og Middelalderborgen

English Heritage og Middelalderborgen http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/the-great-siege-of-dover-castle-1216/ Rasmus Frilund Torpe Studienr. 20103587 Aalborg Universitet Dato: 14. september 2018 Indholdsfortegnelse Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Indledning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Problemstilling ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kulturarvsdiskussion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diskussion om kulturarv i England fra 1980’erne og frem ..................................................................... 5 Definition af Kulturarv ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hvordan har kulturarvsbegrebet udviklet sig siden 1980 ....................................................................... 6 Redegørelse for Historic England og English Heritage .............................................................................. 11 Begyndelsen på den engelske nationale samling ..................................................................................... 11 English -

Launceston Main Report

Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration Launceston HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Objective One is part-funded by the European Union Cornwall and Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration LAUNCESTON HES REPORT NO 2005R051 Peter Herring And Bridget Gillard July 2005 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Environment and Heritage, Planning Transportation and Estates, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements This report was produced by the Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey project (CSUS), funded by English Heritage, the Objective One Partnership for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (European Regional Development Fund) and the South West of England Regional Development Agency. Peter Beacham (Head of Designation), Graham Fairclough (Head of Characterisation), Roger M Thomas (Head of Urban Archaeology), Ian Morrison (Ancient Monuments Inspector for Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly) and Jill Guthrie (Designation Team Leader, South West) liaised with the project team for English Heritage and provided valuable advice, guidance and support. Nick Cahill (The Cahill Partnership) acted as Conservation Supervisor to the project, providing vital support with the characterisation methodology and advice on the interpretation of individual settlements. Georgina McLaren (Cornwall Enterprise) performed an equally significant advisory role on all aspects of economic regeneration. The Urban Survey team, within Cornwall County Council Historic Environment Service, is: Kate Newell (Urban Survey Officer), Bridget Gillard (Urban Survey Officer) Dr Steve Mills (Archaeological GIS Mapper) and Graeme Kirkham (Project Manager). Bryn Perry-Tapper is the GIS/SMBR supervisor for the project and has played a key role in providing GIS training and developing the GIS, SMBR and internet components of CSUS. -

Excavations at Launceston Castle Cornwall

Clay Tobacco Pipes from Excavations at Launceston Castle Cornwall D A Higgins 2006 Excavations at Launceston Castle Edited by A Saunders Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 24 December 2006 xviii + 490 pages 2 colour plates 2 fold-outs paperback ISBN: 978 1904350 75 0 14 PIPE CLAY OBJECTS D A Higgins 14.1 CLAY TOBACCO PIPES the site was allocated a numeric code (24) and a running sequence of context numbers employed. The The excavations produced a total of 3438 fragments site code and context number were marked on the of pipe comprising 501 bowl, 2875 stem and 62 mouth fragments in ink (e.g. 24/491). piece fragments. The fragments range in date from During the initial post-excavation work in the 1970s around 1580 to 1920, thus covering almost the entire and 80s the pipe fragments were first sorted according range of pipe use in Britain. This is a very substantial to the various excavation areas, which were designated assemblage of pipes from one site and it is one of by a letter code, and then into different 'phased the largest excavated assemblages recovered from groups', which were identified using Roman numerals. anywhere in the country. It is also extremely signifi The pipes from each area and phase group were cant for Cornwall where the author's 1988 survey then further subdivided according to the attributes of museum collections located only 38 17th-century of the pipe fragments into groups comprising stems, stamped marks from the whole county, a number bowls, marked pieces, etc. The fragments were not almost doubled by the finds from this one site. -

Lordship of Chorlton

Barony of Cardinham Cardinham Principle Baronies Seat/County Cornwall source IJ Saunders Date History of Lordship Monarchs 871 Creation of the English Monarchy Alfred the Great 871-899 Edward Elder 899-924 Athelstan 924-939 Edmund I 939-946 Edred 946-955 Edwy 955-959 Edgar 959-975 Edward the Martyr 975-978 Ethelred 978-1016 Edmund II 1016 Canute 1016-1035 Harold I 1035-1040 Harthacnut 1040-1042 Edward the Confessor 1042-1066 Harold II 1066 1066 Norman Conquest- Battle of Hastings William I 1066-1087 Post 1066 Richard fitz Turold (or Turolf) is the 1st Baron of Cardinham (although it is not called this until the 12th century) subject to the authority of Reginald, Earl of Cornwall. Richard holds Cardinham Castle, Restormel Castle, Penhallam Castles and is the steward of Robert de Mortain (half brother of William the Conqueror). The barony measures 71 knight’s fees which is extremely large. 1086 Domesday William II 1087-1100 1103-06 Richard dies leaving a son and heir William fitz Richard, the 2nd Baron. 1135 William is given custody of the Royal Castle of Launceston by Henry I 1100-35 King Stephen. 1140 With the invasion of England William switches allegiance and Stephen 1135-54 admits Reginald (one of Henry I’s illegitimate sons) to Launceston Castle. He also gives one of his daughters in marriage to Reginald effectively handing over control of Cornwall. King Stephen initially tries to stop the union but accepts it and makes Reginald Earl of Cornwall. Unknown William dies leaving a son and heir Robert fitz William, the 3rd Baron. -

Two Castles Trail

BUSINESS REPLY SERVICE Licence No. EX. 70 Two Castles Trail Two Castles Trail Meander through rolling countryside full of Meander through rolling countryside full of 2 history on this 24 mile waymarked walking history on this 24 mile waymarked walking route between Okehampton and route between Okehampton and Launceston Castles Launceston Castles COUNTRYSIDE TEAM DEVON COUNTY COUNCIL LUCOMBE HOUSE COUNTY HALL Passing Okehampton Castle, TOPSHAM ROAD the route climbs onto the north- EXETER western corner of Dartmoor EX2 4QW before bearing away past a number of historic settlements The Two Castles Trail is a dating back to the Bronze Age, recreational route for Iron Age and the Normans. walkers of 24 miles, running Sites of defensive historic hill from Okehampton Castle in forts are near to the route, as is the east to Launceston the site of a battle between the Castle in the west. Fold here and secure Saxons and the Celts. The route includes a number of using sticky tape The area is far quieter now, and climbs and descents and before posting offers a great opportunity to crosses a variety of terrain enjoy a range of landscapes and including stretches of road, a sense of walking deep in the woodland tracks, paths through countryside away from the fields, and open crossings of beaten track. moor and downs. The route is divided into 4 stages, and there are a number of opportunities to link to buses along the route. This document can be made available in large print, This is printed on 100% recycled paper. tape format or in other When you have finished with it please recycle languages upon request. -

Illustrated Catalogue of Magic Lanterns

OUR SPECIALTIES. 2. 3. 4. and Stereopticon Com- I —Dr. McIntosh Solar Microscope 5. bination. —McIntosh Combination Stereopticon. — McIntosh Professional Microscope. —Mclntosh-lves Saturator. —McIntosh Sciopticon. 6—Everything in Projection Apparatus. will be supplied Specialties manufactured or sold by other houses furnished to illustrate almost any at their advertised prices. Slides colored slides painted to order by the best artists of •ubject ; also the day. We have a commodious room fitted up to exhibit the practical working of our apparatus to prospective purchasers. TERMS. Registered Let- i. —Cash in current funds, which may be sent by sent C. O. D., ter, Draft, Postal Money Order or Express. Goods balance provided twenty-five per cent of bill is sent with order, the to be collected by the Express Company. greatest care to avoid 2 —All goods will be packed with the foi them breakage in transportation, but we cannot be responsible after leaving our premises, except under special contract. reported within ten days from 3. —Any errors in invoice must be receipt of goods. all no old stock. Our Goods are new ; we have and Nos. 141 AND 143 Wabash Ave„ CHICAGO, ILLS., U. S. A. ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE Stereopticons, Sciopticons, DISSOLVING VIEW APPARATUS, MICROSCOPES, SOLAR MICROSCOPE STEREOPTICON COMBINATION, OBJECTIVES, PHOTOGRAPHIC TRANSPARENCIES, Artistically Colored Views and Microscopical Preparations. MANUFACTURED AND IMPORTED BY THE OPTICAL DEPARTMENT OP THE McIntosh Battery and Optical Co., Nos. 141 and 143 Wabash Ave, CHICAGO, ILLS,, U. S. A. THE WORLD’S INDUSTRIAL -A-isrio C&tlott Centennial ^Exposition* GEI^FIBIGAJFE OB AWAI^D dr. ^zccinBrTOSE:, UNITED STATES, FOE SOLAS MICROSCOPES AND OPTICAL INSTBUIEMTS, Sc. -

Discovery Trail

Discovery Trail Discover the Tamar Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty along this 30-mile walking route. Waymarkers guide you through scenic woodland, historic river quays and rural villages. uty a l be a tur a nding n a outst © Jo Pridham www.tamarvalley.org.uk www.devon.gov.uk/walking Follow the apple! Introduction The Tamar Valley is a designated ‘Area of Outstanding Page 7 Natural Beauty’ nestled between Dartmoor, Bodmin With the help of Moor and the this leaflet you can follow the apple south coasts signs from Plymouth, of Devon and or access the trail at Cornwall. any of the points Page 8 Page 6 shown below. Many people choose to combine a walk with the Tamar Valley Line train service to make a circular route, or take in one of the many villages along the trail for some well earned refreshment. More details of the wider area can be found by using Ordnance Survey Explorer 108. Page 5 Before you head out onto the trail: Some sections of the trail are uneven, sturdy shoes or boots should be worn. Dress according to the conditions, and take water with you even on a cloudy day. Most of the villages Page 3 you encounter along the Discovery Trail have a shop, a pub or a café, but don’t rely on them for your refreshments – always take more Page 4 than you think you will need. If you plan to use the bus, train or ferry as part of your day out, make sure you check the up-to-date timetables first (see back page for links). -

Research News Issue 7

NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH HERITAGE RESEARCH DEPARTMENT Inside this issue... RESEARCH Introduction ...............................2 DEVELOPING NEWS METHODOLOGIES Developing the use of satellite systems for Research Department surveys ...............3 Metric Survey and Historic Scotland: reinforcing skills and links .....................................6 Recording by pixels ..................8 NEW DISCOVERIES AND INTERPRETATIONS The burials from the deserted village of Wharram Percy ... 12 Dowdeswell, Gloucestershire: reassessing the scheduled Romano-British camp ............16 Treludick House, Cornwall .. 18 NOTES & NEWS ................. 22 RESEARCH DEPARTMENT REPORTS LIST ....................... 26 Developing the use of satellite systems for Research Department surveys - story on page 3 NEW PUBLICATIONS ......... 28 NUMBER 7 AUTUMN 2007 ISSN 1750-2446 RESEARCH THEMES AND PROGRAMMES A Discovering, studying and defining historic assets and In this issue of Research News we focus on the development of methodologies their significance and also on some of the new discoveries and interpretations that recent work in A1 What’s out there? Defining, Research Department has generated. characterising and analysing the historic environment A2 Spotting the gaps: Analysing The development of new methodologies and the updating of others, particularly in poorly-understood landscapes, areas the light of technological advances in some of the hardware and software essential and monuments to our work, allow us to sharpen the tools employed in our research activities. The A3 Unlocking the riches: Realising the potential of the research dividend first three articles look at the wide-ranging impact of new techniques. In the area of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) greater coverage and new equipment B Studying and establishing the socio-economic and other has allowed surveyors to position themselves and their surveys in the field far values and needs of the more effectively, leading to savings of time in later data transfer and analysis work. -

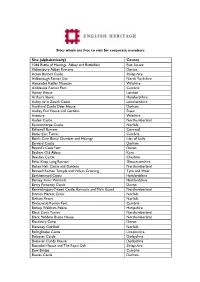

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Medieval Irish Buildings, 1100-1600 Ratty Castle in Co

Book Reviews: Medieval Irish Buildings 1100-1600 tions of historical materials, thereby enabling them to conduct independent research in a com- petent and thorough manner.’ The author has three aims: to enhance the experience of visit- ing medieval buildings; to highlight the basic tools that are required in order to identify medi- eval buildings; to explain how buildings in a medieval society worked. The author stresses in his introduction one aspect of the book that is particularly relevant to castellologists: that in spite of recent books on Irish castles, he consid- ers that ‘there is a need for new perspectives on some individual buildings and on most castle types, and especially on castle terminology both medieval and modern, so two chapters carry that burden here.’ (p. 16). The first two chapters cover architectural styles and approaches to the study of medieval build- ings, whether ecclesiastical buildings, castles or urban architecture, whilst the third is devoted to ecclesiastical architecture. The value of spatial analysis of buildings has been illustrated on a number, albeit too few, of occasions, from Patrick Faulkner’s seminal paper (1963) on- wards. O’Keeffe builds on Rory Sherlock’s introduction to that impressive building, Bun- Medieval Irish Buildings, 1100-1600 ratty Castle in Co. Clare (2011) to analyse the Author: Tadhg O’Keeffe access arrangements from ground floor to the Publisher: Four Courts Press fourth, as well as the mezzanine level (Fig. 41). Series: Maynooth Research Guides for Irish The final two chapters are those on castles, the Local History no. 18 fourth on the period from the Anglo-Norman Publication date: 2015 invasion through to the Black Death, with the Paperback: 320 pages fifth continuing the story to the plantation era.