Chapter Five – Surviving the Great Depression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau Und Bootsbau

Karosseriekonzepte und Fahrzeuginterior KFI INSPIRATIONEN DURCH AERODYNAMIK, FLUGZEUGBAU UND BOOTSBAU Dipl.-Ing. Torsten Kanitz Lehrbeauftragter HAW Hamburg WS 2011-12 15.11.2011 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen durch Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau, Bootsbau 1 „Ein fortschrittliches Auto muss auch fortschrittlich aussehen “ Inspirationen durch Raketenbau / Torpedos 1913, Alfa-Romeo Ricotti Eine Vereinigung von Torpedoform und Eiförmigkeit Formale Aspekte im Vordergrund Bildquelle: /1/ S.157 aus: ALLGEMEINE AUTOMOBIL-ZEITUNG Nr.36, 1919 Ein Bemühen, die damaligen Erkenntnisse aus aerodynamischen Versuchen für den Automobilbau 1899 anzuwenden. Camille Jenatzy Schütte-Lanz SL 20, 1917 „Der rote Teufel“ Zunächst: nur optisch im Jamais Contente (Elektroauto) Die 100 km/h Grenze überschritten Bildquelle: /1/ S.45 Geschwindigkeitsrennen waren an der Tagesordnung aus: LA LOCOMOTION AUTOMOBILE, 1899 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen durch Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau, Bootsbau 2 Inspirationen durch 1906 Raketenbau / Torpedos Daytona Beach „Stanley Rocket “ mit Fred Marriott Geschwindigkeitsweltrekord für Automobile mit Dampfantrieb mit beachtlichen 205,5 km/h Ein Bemühen, die damaligen Erkenntnisse aus aerodynamischen Versuchen für den Automobilbau Elektrotechniker anzuwenden. bedient Schaltungen Zunächst: nur optisch 1902 W.C. Baker Elektromobilfabrik 7-12 PS Elektromotor Torpedoförmiges Fichtenholzgehäuse Bildquelle: /1/ S.63 aus: Zeitschr. d. Mitteleuropäischen Motorwagen-Vereins, 1902 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen -

Chronological Histories Olamerican Car Makers

28 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS (1940 ALMANAC ISSUE) Chronological Histories ol American Car Makers (Continued from Page 26) Chrysler Corp. “ Total Cadillac-LaSalle—Cont’d Produc- Price Year Models tion Range* Factories Milestone. Voftf (Total All Units Tkm of Cin Sales to Body Style List Mlleitonee Dealers (Typical Car) Price — Produced 1925 Maxwell 4 137,668 Maxwell 4 Touring Highland Park Chryeler Chrysler Six 5895 to Chrysler Newcastle automotive design andfj 6.000,000 tooling rearrangement Six Sedan $2065 Evansville time In 1932 V-S LaS. J45-B 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 2.645 Over spent for and Jew, the V-8 366-B 9,253 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 3.095 for complete line of new models. Super-safe head- fig g; 3,796 on Cadillac cars. Aircooled Kercheval compression engines safety’ V-12 370-B 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) lights first introduced Dayton bodies, JS V-16 462-B 5-P. Sedan 5,095 generator; completely silent transmission; full range air cleaners equipment. Chrysler Corp. organizedanJh3*?* • ride regulator. Wire wheels standard "i"*” iHM?' 1933 V-8 LaS. 346-C 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 2,495 v-16 production restricted to 400 cars. Fisher no-draft asraaray V-8 356-C 6,839 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 2.995 ventilation. LaSalle first American made car with Cn -* V-12 370-C 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 1.685 spare tire concealed within body. sxxir«. s V-16 452-C 5-P. Fleetwood sedan B^so Coupe) to supply Chrysler 58 170.392 Chrysler 58 Touring Highland Pork Introduced rubber 1834 Str. -

PLYMOUTH OWNERS CLUB JUDGING GUIDE Group 1 1928

1 PLYMOUTH OWNERS CLUB JUDGING GUIDE Group 1 1928 - 1939 I - Club Policy On Modified Cars page 3 II – Classes, Awards and Trophies (Revised 2004) page 5 III – Restoration, Policy and Judging page 7 IV - Worksheet Guides page 9 Check List for Group I engine codes page 14 V - Technical Advisor Comments page 17 1928-29 Q page 18 1929-30 U page 20 1931 PA page 23 1932 PB page 24 1933 page 25 1934 page 26 1935 page 30 1936 page 32 1937 page 34 1938 page 36 1939 page 38 1935-41 Ply Commercial page 39 Fargo Commercial page 41 Revised – January 2010 2 I - Club Policy The purpose of the Club is to encourage the use, preservation and restoration of Plymouth and Fargo automobiles and trucks, 25 years of age or older, particularly the AUTHENTIC restoration of these models, to provide and regulate meets, tours and exhibitions for members vehicles, to provide high judging standards at these meets, to publish in the club magazine information of interest and value to the members, and to discourage any activities, ideas or philosophies contrary to these aims. This paragraph certainly gets directly to the issue we are dealing with. We are to promote the AUTHENTIC restoration of Plymouths and Fargo vehicles. That means we need to judge these cars against a standard of a factory shipped car. Original Plymouths did not come from the factory with modern modifications. Changes made due to state safety requirements are acceptable, such as safety glass, seat belts and turn signals. If any vehicle has been modified in such a way as to obviously alter horse power, and components to include; rear end, transmission, suspension, electrical system, sheet metal, such as a street rod, it shall be ineligible for judging. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Download Chapter 119KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 128 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 129 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 1910–1996 WRITTEN BY JAMES W. FURLONG SUBMITTED BY THE NAE HOME SECRETARY GEORGE J. HUEBNER, JR., one of the foremost engineers in the field of automotive research, was especially noted for developing the first practical gas turbine for a passenger car. He died of pulmonary edema in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on September 4, 1996. George earned a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan in 1932. He began work in the mechanical engineering laboratories at Chrysler Corporation in 1931 and completed his studies on a part- time basis. He was promoted to assistant chief engineer of the Plymouth Division in 1936 and returned to the Central Engineering Division in 1939 to work with Carl Breer, one of the three engineers who had designed the first Chrysler vehicle fifteen years earlier. George was especially pleased to work for Breer, whom he regarded as one of the most capable engineers in the country. Breer established a research office in 1939 and named George as his assistant. It became evident to George that he should bring more science into the field. When he became chief engineer in 1946, he enlarged the activities of Chrysler Research into the fields of physics, metallurgy, and chemistry. He was early to use the electron microscope. George also was early to see the need for digital computers in automotive engineering. Largely in recognition of this pioneering work, he was awarded the Buckendale Prize for computer- Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Tj 'WMYAITO-Fiwgraphy

46 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS, OCTOBER 14, 1940 thought of the high command, had dug up the capital to launch the lobby 0f tuT Commodore, then the enterprise, Joe Fields, who knew practically crJ? * and veteran of the automobile show every worth-while dealer in the country, had, as vice- several big Tj manufacturers h 'WMYAITO-fiWGRAPHY the plays as well as 1 saga president and general sales manager, guaranteed being i n thai 4l|ft| TOE of the first retail outlets so necessary to launching this new product. itself. Joe suggested the 100 YEARS CN dore and Walter P. toM RUBEER All bases had been covered and the new automobile hire the lobby, adding, “w,Su was industry. So when a show all right.” set to blitzkrieg the automobile And J OV* the Studebaker deal was abruptly terminated, Chrysler vanishing act—a short oneZJr same ing with the right name was set to go. His plans were so perfected that the dotted line of the off he gave the go-ahead necessary day negotiations were broken ment which permitted him f to the late Theodore F. MacManus, who already had the boss: "We own the Chapter XCII—The Probably it ”b£' Chrysler Corp. written his advertising copy. The baby had been born. was just as Mark Twain created advertising broadside Chrysler had to show Pudd’nhead Wilson half a century Well I remember the stir this outside * ago and made him created, boldness way, for the Commodore lobhv as famous as A. Conan Doyle did his of the newcomer in the industry the as good as a ringside bherlock Holmes. -

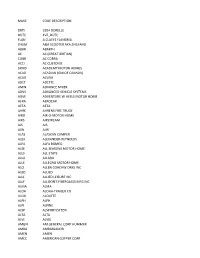

Reg Makes Sorted by Company Name

MAKE CODE DESCRIPTION DRTI 1954 DORELLE DUTC 4VZ_DUTC FLAN A CLAEYS FLANDRIA ZHUM A&A SCOOTER AKA ZHEJIANG ABAR ABARTH AC AC (GREAT BRITIAN) COBR AC COBRA ACCI AC CUSTOMS SKMD ACADEMY MOTOR HOMES ACAD ACADIAN (GM OF CANADA) ACUR ACURA ADET ADETTE AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE W HEELS MOTOR HOME AERA AEROCAR AETA AETA AHRE AHRENS FIRE TRUCK AIRO AIR-O-MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX ALEXANDER-REYNOLDS ALFA ALFA ROMEO ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS ALL STATE ALLA ALLARD ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI ALLEN COACHW ORKS INC ALED ALLIED ALLL ALLIED LEISURE INC ALLF ALLISON'S FIBERGLASS MFG INC ALMA ALMA ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU ALOUTTE ALPH ALPH ALPI ALPINE ALSP ALSPORT/STEEN ALTA ALTA ALVI ALVIS AMGN AM GENERAL CORP HUMMER AMBA AMBASSADOR AMEN AMEN AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER INC AEAG AMERICAN EAGLE AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AIH AMERICAN IRONHORSE MOTORCYCLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMLF AMERICAN LIFAN IND INC AMI AMERICAN MICROCAR INC AMER AMERICAN MOTORS AMPF AMERICAN PERFORMANCE AMQT AMERICAN QUANTUM AMF AMF AMME AMMEX AMPH AMPHICAR AMPT AMPHICAT AMTC AMTRAN CORP ANGL ANGEL APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA USA,INC. ARCA ARCTIC CAT ARGO ARGONAUT STATE LIMOUSINE ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL ARGYLE ARIE ARIEL (BRITISH) ARIT ARISTA ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMS ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY ARNO ARNOLT-BRISTOL ARO ARO OF N.A. ARRO ARROW ARTI ARTIE ASA ASA ARSC ASCORT ASHL ASHLEY ASPS ASPES ASVE ASSEMBLED VEHICLE (NO MFR VIN) ASTO ASTON-MARTIN ASUN ASUNA -

F/K/A Chrysler LLC), Et Al., (Jointly Administered) Debtors

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------------------------------- In re Chapter 11 Old Carco LLC Case No. 09-50002 (AJG) (f/k/a Chrysler LLC), et al., (Jointly Administered) Debtors. ----------------------------------------------------------------- DISCLOSURE STATEMENT WITH RESPECT TO SECOND AMENDED JOINT PLAN OF LIQUIDATION OF DEBTORS AND DEBTORS IN POSSESSION Alpha Holding LP 09-50025 (AJG) DCC 929, Inc. 09-50017 (AJG) Dealer Capital, Inc. 09-50018 (AJG) JONES DAY Global Electric Motorcars, LLC 09-50019 (AJG) NEV Mobile Service, LLC 09-50020 (AJG) Corinne Ball NEV Service, LLC 09-50021 (AJG) Old Carco LLC 09-50002 (AJG) 222 East 41st Street (f/k/a Chrysler LLC) New York, New York 10017 Old Carco Aviation Inc. 09-50003 (AJG) Telephone: (212) 326-3939 (f/k/a Chrysler Aviation Inc.) Facsimile: (212) 755-7306 Old Carco Dutch Holding LLC 09-50004 (AJG) (f/k/a Chrysler Dutch Holding LLC) Old Carco Dutch Investment LLC 09-50005 (AJG) David G. Heiman (f/k/a Chrysler Dutch Investment LLC) North Point Old Carco Dutch Operating Group LLC 09-50006 (AJG) 901 Lakeside Avenue (f/k/a Chrysler Dutch Operating Group LLC) Old Carco Institute of Engineering 09-50007 (AJG) Cleveland, Ohio 44114 (f/k/a Chrysler Institute of Engineering) Telephone: (216) 586-3939 Old Carco International Corporation 09-50008 (AJG) Facsimile: (216) 579-0212 (f/k/a Chrysler International Corporation) Old Carco International Limited, L.L.C. 09-50009 (AJG) (f/k/a Chrysler International Limited, L.L.C.) Jeffrey B. Ellman Old Carco International Services, S.A. 09-50010 (AJG) 1420 Peachtree Street, N.E. -

Mopar Brake Drums

Mopar brake drums Year Description Part# Price each Qty notes 1934 Rear Ply PF , PG M05577 $125.00 1 1934-35 F&R Ply, CHR, DES M05856 $150.00 2 1957-59 Front 11” X21064 $125.00 1 Chk notes in book! 1959-61 F & R 11” X21065 125.00 1 Chk notes in book ! 1960-61 Ply & Dart Front X21070 $125.00 1 11X2 1960-61 Ply & Dart X21071 $125.00 2 11X2 1962-69 Dodge & Ply F & R X21074 $125.00 2 1951-54 Dodge X21079 $150.00 2 10” 1963-70 Dart & Valiant Front X21101 2 9” 1951-56 Ply front X21141 $150.00 3 10” 1955-56 Plymouth X21143 150.00 2 11” Front 1957-59 Plymouth F & R X21145 $125.00 4 11X2 1965-69 Dart, Valiant rear X21360 $145.00 2 10” 1965-68 F/S, front X21400 $125.00 4 11 x2 3/4 1968-68 Polara, Monaco , front X21400 See above 1965-67 Ply Fury , Grand Fury X21400 See above 1966-69 Mopar full size front X21458 $95.00 12 11X2 3/4 1969-70 Mopar full size front X21505 $125.00 1 11X2 3/4 1963-69 Mopar full size rear X21373 $125.00 2 11X3 1970-72 Dart & Valiant front X21515 $135.00 3 9X2 1/2 1965-69 Dart & Valiant rear X21565 $85.00 4 10” 1940-41 Desoto S7, S8 right front X22135 $150.00 6 Hub & drum 1938-40 Desoto S5, S6 right rear X22136 $150.00 4 Hub & drum 1937-47 Desoto S7-8, S10-11 X22425 $125.00 1 11” front 1937-47 Desoto S7-8, 10-11 rear X22426 $125.00 8 11” 1940-41 Desoto S7-8 left rear X22993 $150.00 3 Hub & drum 1942-48 Desoto S11 left front X28959 $150.00 3 Hub & drum 1969-72 Full size right front X30644 $125.00 1 Hub & drum 1965-69 Full size right front X30668 $125.00 1 Hub & drum 1936-37 C6, C7 S1, S3 P4 front X31060 $125.00 4 1936 Chry -

Pre-Cut Ready to Install Kits Year • Make • Model Specific 1928-48

1928-48 Early Mopar Catalog Automotive Thermal Acoustic Insulation Dodge Chrysler, Plymouth, Desoto Roof to Road Solutions to Control Passenger Cabin Noise, Vibration and Heat •Reduce Road Noise •Reduce Exhaust Harmonics Pre-Cut Ready to Install Kits •Eliminate Mechanical Noise •Stop Body Panel Vibration Year • Make • Model Specific •Reduce Radiated & Reflected Heat •Stop Audio System Vibration The Coolest Cars Have QuietRIDE Inside! ™ Kits are available for these Vehicles See AcoustiTrunk Catalog Roof Kit Roof & Quarter Panels above beltline. Cowl Kit Panels between the firewall and front door of the vehicle. Trunk Floor Kit Trunk Floor & Tire Well Firewall Insulator Fits under dash against the firewall bulkhead. Door Kit All Doors Body Panel Kit All Panels below the beltline including Package Tray, Seat Divider, Rear Wheel Wells, Fenders, Rear Quarters and Tail Panels (As Required) Floor Kit Front Floor, Rear Floor, Transmission Hump/ Driveline Everything in One Box to Do the Job Right! Pre-Cut, Ready To install Kits are Year, Make and Model Specific and include: •Dynamat Xtreme •Heat Shield Barrier Insulation Order Line: 888-777-3410 Tech Line: 209-942-4777 •Spray Adhesive •Seam Tape Fax: 877-720-2360 •Illustrated Instructions 1122 S. Wilson Way Ste. #1, Stockton CA, 95205 For more information contact us at: [email protected] ©2003-21 •Prices Subject to Change Without Notice 1935-2014 1928-48 Ram/Dodge Truck Catalog Early Mopar Catalog Automotive Thermal Acoustic Insulation Dodge Chrysler, Plymouth, Desoto Roof to Road Solutions to Control Passenger Cabin Noise, Vibration and Heat Introducing a multi-stage, automotive insulation and sound damping system to give MOPAR cars the “quiet riding comfort” found in today’s new cars. -

Finding Aid for Charles Hyde Chrysler Corporate History Research Papers, Circa 1995-2003

Finding Aid for CHARLES HYDE CHRYSLER CORPORATE HISTORY RESEARCH PAPERS, circa 1995-2003 Accession 2013.141 Finding Aid Published: 3 December 2019 Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Charles Hyde Chrysler Corporate History Research Papers, circa 1995-2003 Accession 2013.141 OVERVIEW REPOSITORY: Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Blvd Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 www.thehenryford.org [email protected] ACCESSION NUMBER: 2013.141 CREATOR: Hyde, Charles K., 1945- TITLE: Charles Hyde Chrysler Corporate History Research Papers INCLUSIVE DATES: circa 1995-2003 QUANTITY: 4.7 cubic ft. LANGUAGE: The materials are in English. ABSTRACT: The Charles Hyde Chrysler Corporate History Research Papers, circa 1995-2003, contains photocopies of documents Hyde used in the writing of his book, Riding the Roller Coaster: A History of the Chrysler Corporation. The information in the photocopies relates to Walter P. Chrysler and his company's history, from 1875-2002. Also included are annual reports from 1993-2000 as well as a draft of the manuscript. Page 2 of 8 Charles Hyde Chrysler Corporate History Research Papers, circa 1995-2003 Accession 2013.141 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The collection is open for research. COPYRIGHT: Copyright has been transferred to The Henry Ford by the donor. Copyright for some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator(s). ACQUISITION: Donated to The Henry Ford, 2013. RELATED MATERIAL: Related material held by The Henry Ford: -Charles Hyde Automotive Research Papers, circa 2003- 2013, Accession 2015.73 Related collections beyond The Henry Ford: -Charles K. -

Body Group Grille and Bumper Interchange

BODY GROUP 137 GRILLE AND BUMPER INTERCHANGE I '- 211 1648747-8 14.25 238 1686482-3 5.75 350 2276146 3.70 186 426334-3 '51 200 -Dart '63-64 446183-2 '51 exc 20 -Chrvsler '56 Windsor I; Imperial '57-58 New Yorker 239 1820058- 9 23.65 351 31. 25 G '52 -~hrysler 2266468 w/guards Packard '51-52 212 1403877 obs '58 __ -Chrysler '51-52 240 1541088 obs 9.70 2266469 w/o 187 1543528 Dart '63-64 -Packard '57 213 1373138-9 obs Chrysler '54 353 2461300 47.00 Packard '58 exc Hawk -Chrysler '51-53 Imperial '54 -Dodge '65 Coronet ser New Yorker 241 1541501-2 47.10 Packard '57 Clipper Plymouth '65 214 1346679 25.95 -Chrysler '55. -56 300 188 1407820-1 Belvedere ser -Desoto '52-53 -Chrysler '51-52 Windsor Imperial '55-56. 354 2448270--1 1.60 G Saratoga 295 2275211-2 1.05 Amber 189 1. 90 Chrysler '53 Valiant '62-63 Chrysler '63 134653~ 1753435 In 215 1 5.75 296 72.50 Dodge '63-64 880 ser 1753436 Out -Chrysler '51-52 Windsor - 2266492 355 2424862- 3 S.20 Desoto '59-61 {; Saratoga wIguard holes -Valiant '64-65 e xc Dodge '58 Chrysler '53 Windsor 2266491 Barracuda Dodge '60-66 216 1346532 obs wlo guard holes 356 29.50 Plymouth '58-66 Chrysler '51-52 Windsor Dodge '63-64880 ser 2404520 w/guards Chrysler '58- 66 [ Saratoga Chrysler '63 2404521 wlO Valiant '6~62 Chrysler '53 297 2248299 obs Valiant '64-65 Lancer '61-62 217 1324634-5 obs 14.