Lillie Bridge Grounds, Opened in 1869

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

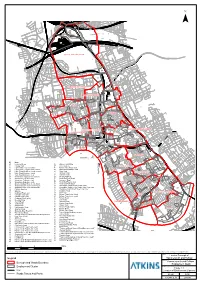

Legend Borough and Wards Boundary Employment Cluster Rail

01 03 02 04 05 07 06 COLLEGE PARK AND OLD OAK 08 10 11 WORMHOLT AND WHITE CITY 12 SHEPHERD'S BUSH GREEN 13 20 17 16 19 ASKEW 24 14 15 25 22 ADDISON 23 18 27 21 28 29 26 41 40 43 42 AVONMORE AND BROOK GREEN HAMMERSMITH BROADWAY 44 RAVENSCOURT PARK 30 45 56 36 38 46 55 31 34 59 33 35 37 47 39 32 49 57 60 50 48 NORTH END 51 58 ID Name 62 61 01 Letchford Mews 46 Hammersmith Road 02 College Park 47 Coret Gardens 53 FULHAM REACH 68 03 Hythe Road Emp Zone (east) 48 Fulham Place Road north 67 64 04 Hythe Road Emp zone north central 49 Hammersmith Bridge Road 05 Hythe Road Emp Zone (south central) 50 Crisp Road 63 52 69 FULHAM BROADWAY 06 Hythe Road Emp zone south 51 Distillery Road 07 Tythe Road Emp zone west 52 Rainville Road 08 Wood Lane Empployment Zone (N) 53 Greyhound Road 65 10 Wood Lane Emp zone west 55 North End Road North 70 66 11 Wood Lane Emp zone east 56 Avonmore Road 82 12 Wood Lane Emp zone south 57 North End Road Central MUNSTER 13 Shepherds Bush Town Centre North 58 North End Road South 14 Shepherds Bush Town Centre South 59 Kensington Village & Lillie Bridge Depot 71 15 Shepherds Bush Town Centre West 60 Kensington Bridge & Lillie Bridge Depot Emp zone 83 16 Frithville Gardens 61 "Seagrave Road/Rickett Street Emp zone" 84 62 Seagrave Road 79 17 Stanlake 72 PARSONS GREEN AND WALHAM 18 Goldhawk Road east 63 Farm Lane 85 19 Uxbridge Road east 64 Fulham Town Centre North TOWN 20 Uxbride Road (west) 65 Fulham Town Centre south 77 81 21 Goldhawk Road (west) 66 Fulham Road 22 Goodwin Road 67 Lillie Road 78 86 68 Humbolt Road PALACE -

A History of the British Sporting Journalist, C.1850-1939

A History of the British Sporting Journalist, c.1850-1939 A History of the British Sporting Journalist, c.1850-1939: James Catton, Sports Reporter By Stephen Tate A History of the British Sporting Journalist, c.1850-1939: James Catton, Sports Reporter By Stephen Tate This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Stephen Tate All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4487-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4487-1 To the memory of my parents Kathleen and Arthur Tate CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... x Introduction ............................................................................................... xi Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 Stadium Mayhem Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 15 Unlawful and Disgraceful Gatherings Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 33 A Well-Educated Youth as Apprentice to Newspaper -

26/20/77 Alumni Association Alumni Harold M. Osborn Papers, 1917, 1919-83

26/20/77 Alumni Association Alumni Harold M. Osborn Papers, 1917, 1919-83 Box 1: Correspondence A, 1930-31, 1934 M. R. Alexanders, Carl Anderson Amateur Athletic Union, 1944-58, 1961, 1967, 1971 B, 1925-32, 1941, 1943, 1947-48 Douglas Barham, John Behr, Hugo Bezdek, George Bell, Frank Blankley, Frank Brennan, Avery Brundage, Asa Bushnell C, 1924, 1931-32, 1936, 1938-39 Carl Carstensen, Jim Colvin D, 1925-26, 1928, 1932-36 Harry Devoe, George Donoghue, John Drummond, Howard Duncan, T. Duxbury E, 1936, 1940-41 F, 1930-32, 1935-36, 1939-40 Arthur Fast, R.A. Fetzer, Walter Fisher, W. J. Francis Ferris, Daniel F. (AAU), 1928, 1930-39 G, 1930-32, 1936 H, 1928-32 Walter Herbert, Charles Higginbottom, Adolph Hodge I, 1935-36 IOC - Olympic athletes admission to Berlin games J, 1928, 1930-35, 1938-40 Skotte Jacobsson, Kelvin Johnston, B. & C. Jorgensen K, 1928, 1931-32, 1934-36 Thomas Kanaly, J. J. Keane, W. P. Kenney, Robert Kerr Volker Klug and Rainer Oschuetz (Berlin), 1962-69 Volker Klug re “Fosbury Flop,” 1969 Volker Kllug re Junge Welt articles on Decathlon, 1971 L, 1928, 1930-31, 1935-36 A. S. Lamb, James A. Lec, Ben Levy, Clyde Littlefield M, 1929, 1933-36, 1940 Lawrence Marcus, R. Merrill, C. B. Mount N, 1927-28, 1936-37 Michael Navin (Tailteann Games), Thorwald Norling O, 1928, 1930, 1932, 1935-37 Herman Obertubbesing Osborn, Harold, 1925-26, 1931, 1935 P, 1932-38, 1940-41 W. Bryd Page, Paul Phillips, Paul Pilgrim, Marvin Plake, Paul Prehn, Rupert Price, 26/20/77 2 Frank Percival R, 1943, 1949 R. -

Post Office London Clu-Coa

1510 CLU-COA POST OFFICE LONDON CLU-COA CLUBS-WORKI:-!G ME:-!'S &c.-continued. Working Girls' (Miss Catherine M. Lowthin, Milldleton George, Lots road, Chelsea SW & 1 Lee James Samuel, 25 New Compton st WC St. John's Wood (John Tozer), Henry street, supt.), 26 & 28 Eardley crescent SW 18 Danvers street, Chelsea SW MalthollseFredk.& Son,220 Kennington rdS E Portland town NW Working Girls' (Miss Mana Ohater, hon. sec.), Mills & Sons Ltd. 7, 8, 9 & 31 Cam bridge Nelson William & Son, 38 Kennington ru SE St. John's Working Lads' Institute (E. Wilson, 122 Kennington road SE place, Paddin;!ton W & 3 7 Westminster bridge road S E hon. secretary), 39 Hampden road, Upper Working Girls' (Miss Dora Baldwin), 120 Myson Albert Bdward, 21 Kramer mews, Salsbury Lamps Ltd. 11 Long acre WC Holloway N Cornwall road, Lambeth SE Richmond road SW Sandbrook Fredk. Silas, 76 Seymour place W ., St. Margaret's Settlement Girls' (Miss Working Girls' Olub & Institute (Miss May Newman Frederick, 50A, Sutherland square, Smith Oharles, 307 Kingsland road N E Charlotte Bayliss, proprietress), 42 & « Horne. supt.), 150 Long lane SE Walworth SE · Strickett Charles, 78 York st. Portman sq W Union road S E Oak Thomas Charles, 29 St. Luke's mews, Stricklan 1Alfd.Rt.33 Haberdasher st.Hoxtn N St. Mark's (John .Albert Marshall), 97 & 99 St. Luke's road W Thorley Richard, 95 Gray's inn road WC Cobourg road S E CLUB FURNITURE MAKERS. Offord & Sons Limited, 67 Goorge street, Tillman Frank, 46 Lisson grove NW St. Mark's Girls' (Miss Alice Green, hon. -

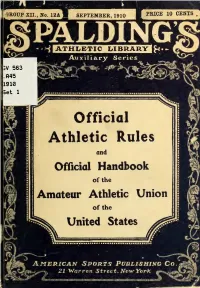

Official Athletic Rules and Official Handbook

GROUP XII., No. 12A VBIC^ 10 CENTS J SEPTEMBER . 1910 K 'H ATHI/BTIC I/IBRARY «^^ Auxiliary Series viy^ Il«" •••;»»"• hV 563 J5i'R P45 'I! 11910 hei 1 A.Gi.Sralding & §ros. .,^. MAINTAIN THEIR OWN HOUSES > • FOR DISTRIBUTING THE Spalding ^^ COMPLETE LINE OF Athletic Goods ••" ';' . r IN THE FOLLOWING CITIES NEW YORK "'izT°I28 Nassau St. "29-33 W«sl 42d SI. NEWARK, N. J. 84S Broad Street BOSTON, MASS. 141 Federal Street Spalding's Athletic Library Anticipating the present ten- dency of the American people toward a healthful method of living and enjoyment, Spalding's Athletic Library was established in 1892 for the purpose of encouraging ath- letics in every form, not only by publishing the official rules and records pertaining to the various pastimes, but also by instructing, until to-day Spalding's Athletic Library is unique in its own par- ticular field and has been conceded the greatest educational series on athletic and physical training sub- jects that has ever been compiled. The publication of a distinct series of books devoted to athletic sports and pastimes and designed to occupy the premier place in America in its class was an early idea of Mr. A. G. Spalding, who was one of the first in America to publish a handbook devoted to sports, Spalding's Official A. G. Spalding athletic Base Ball Guide being the initial number, which was followed at intervals with other handbooks on the in '70s. sports prominent the . , . i ^ »«• a /- Spalding's Athletic Library has had the advice and counsel of Mr. A. -

Earl's Court and West Kensington Opportunity Area

Earl’s Court and West Kensington Opportunity Area - Ecological Aspirations September 2010 www.rbkc.gov.uk www.lbhf.gov.uk Contents Site Description..................................................................................................................... 1 Holland Park (M131).......................................................................................................... 1 West London and District Line (BI 2) ................................................................................. 4 Brompton Cemetery (BI 3)................................................................................................. 4 Kings College (L8)............................................................................................................. 5 The River Thames and tidal tributaries (M031) .................................................................. 5 St Paul's Open Space (H&FL08) ....................................................................................... 5 Hammersmith Cemetery (H&FL09) ................................................................................... 6 Normand Park (H&FL11)................................................................................................... 6 Eel Brook Common (H&FL13) ........................................................................................... 7 British Gas Pond (H&FBI05).............................................................................................. 7 District line north of Fulham Broadway (H&FBI07G)......................................................... -

Lillie Enclave” Fulham

Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 The “Lillie Enclave” Fulham Within a quarter mile radius of Lillie Bridge, by West Brompton station is A microcosm of the Industrial Revolution - A part of London’s forgotten heritage The enclave runs from Lillie Bridge along Lillie Road to North End Road and includes Empress (formerly Richmond) Place to the north and Seagrave Road, SW6 to the south. The roads were named by the Fulham Board of Works in 1867 Between the Grade 1 Listed Brompton Cemetery in RBKC and its Conservation area in Earl’s Court and the Grade 2 Listed Hermitage Cottages in H&F lies an astonishing industrial and vernacular area of heritage that English Heritage deems ripe for obliteration. See for example, COIL: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1439963. (Former HQ of Piccadilly Line) The area has significantly contributed to: o Rail and motor Transport o Building crafts o Engineering o Rail, automotive and aero industries o Brewing and distilling o Art o Sport, Trade exhibitions and mass entertainment o Health services o Green corridor © Lillie Road Residents Association, February1 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Stanford’s 1864 Library map: The Lillie Enclave is south and west of point “47” © Lillie Road Residents Association, February2 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Movers and Shakers Here are some of the people and companies who left their mark on just three streets laid out by Sir John Lillie in the old County of Middlesex on the border of Fulham and Kensington parishes Samuel Foote (1722-1777), Cornishman dramatist, actor, theatre manager lived in ‘The Hermitage’. -

Masonic Magazine : Freemasonry

TJH E MASONIC MAGAZINE : % SMfrlg digest nf FREEMASONRY IN ALL ITS BRANCHES ^ (SUPPLEMENTAL TO " THE FREEMASON. ") VOL V. UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF HIS EOYAL HIGHNESS THE PEINCE OF WALES, K.G. The M. W. Grand Master. ENGLAND. SIR MICHAEL EOBEET SHAW-STEWAET, BAET., The M. W. Grand Master. THE EIGHT HONOUEABLE THE EAEL OF EOSSLYN, The M.W. Past Grand Master. SCOTLAND. COLONEL FEANCIS BUEDETT, Representative for Gmnd Lodge. IRELAND. AND THE GEAND MASTERS OF MANY FOREIGN GEAND LODGES. LONDON : GEOEGE KENNING, 198, FLEET STEEET. 1877-8. PEEFACE L TO THE FIFTH VOLUME, n —?— i TXTE have arrived at our Fifth Volume, and a few words of Preface are customary and needful. Not, indeed, that Ave have very much to say. i- E , We betray no secrets, and we reveal no mysteries, when we mention once again ' ' that were Masonic Literature to be supported alone by the patronage of our Craft, we fear that the result would be a very limited " outcome " indeed,—very far from a " strong order." If our good Publisher only measured the " Supply " r ', he so liberally provides for the " pabulum mentis Latomicse " by the " Demand ," ¦*, which hails and encourages his sacrifices, we are inclined to fancy, though it is *; only our own private opinion, " quantum valet," that the status of Masonic Lite- rature amongst us would be neither very promising nor flattering ;—nay its very appearances, " like angels' visits," must he " few and far between." Despite our excellent friend Bro. Hubert's complimentary estimate of English Masonic Literature, we feel hound honestly to admit that there is a " little " room for an improved taste and more extensive patronage ! But yet Ave do not i Avish to seem to write in a spirit of complaint or fault, especially at the conclu- sion of our Fifth Volume ! For with such a fact before us, we must really beg to congratulate our Order on gallant efforts, resolutely made, to diffuse amongst | | our Craft a sound, sensible, readable, healthy Masonic Literature. -

Nº II-2016 4-7-2016.Pmd

Revista de Estudios Extremeños, 2016, Tomo LXXII, Número II, pp. 1091-1118 1091 O corneteiro de Badajoz JACINTO J. MARABEL MATOS Doctor en Derecho Comisión Jurídica de Extremadura [email protected] RESUMEN: La presencia del ejército portugués en Extremadura, durante la mayor parte de los combates que se libraron en la Guerra de la Independencia, fue constante. Sin embargo, los escasos estudios dedicados a recoger esta partici- pación suelen estar basados en fuentes interpuestas, fundamentalmente británi- cas, y por lo tanto incompletas. Por ello, en ocasiones resulta complicado delimitar los hechos históricos de los meramente fabulados, como ocurrió en el caso del corneta del batallón de cazadores portugueses nº 7, en el asalto de Badajoz de 1812. En este trabajo tratamos de mostrar las posturas enfrentadas en torno a esta particular historia de la que, aún hoy, es difícil asegurar su veracidad. PALABRAS CLAVE:Sitio de Badajoz; Ejército Portugués; Corneteiro. ABSTRACT The presence of the Portuguese army in Extremadura, during most of the battles that were fought in the Peninsular War, was constant. However, few studies dedicated to collecting this participation are often based on filed, mainly british sources, and therefore incomplete. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to delineate the historical facts of the fabled merely, as in the case of portuguese bugle batalhão caçadores nº 7, in the assault of Badajoz in 1812. In this work we show opposing positions around this particular story that even today is difficult to ensure its accuracy. KEYWORDS: : Siege of Badajoz; Portuguese Army; Corneteiro. Revista de Estudios Extremeños, 2016, Tomo LXXII, N.º II I.S.S.N.: 0210-2854 1092 JACINTO J. -

Capital & Counties Properties

Capital & Counties Properties PLC February 2019 Our assets Our assets are concentrated around two prime estates in central London with a combined value of £3.3 billion Covent Garden 100% Capco owned Earls Court Properties 1 Earls Court Partnership Limited; an investment vehicle with TfL, Capco share 63% 2 Lillie Square 50:50 a joint venture with KFI CLSA Land Capco has exercised its option under the CLSA to acquire LBHF land TfL Lillie Bridge Depot 100% TfL owned Consented Earls Court Masterplan 1 2 Key Covent Garden Earls Court Properties LBHF TfL The landowners’ map above is indicative. 100% Capco owned The Earls Court Lillie Square Capco has exercised Lillie Bridge Depot Consented The Covent Garden area has been magnified x 1.95 Partnership Limited; 50:50 its option under 100% TfL owned Earls Court Masterplan* an investment joint venture the CLSA relating vehicle with TfL with KFI to this land All figures relate to the year ended 31 December 2018 and represent Capco’s share of value. Capco share 63% *excludes the Empress State Building which has separate consent for residential conversion 1 The Earls Court landowners map above is indicative. 2 Key Covent Garden Earls Court Properties LBHF TfL 100% Capco owned The Earls Court Lillie Square Capco has exercised Lillie Bridge Depot Consented Partnership Limited; 50:50 its option under 100% TfL owned Earls Court Masterplan* an investment joint venture the CLSA relating vehicle with TfL with KFI to this land Capco share 63% *excludes the Empress State Building which has separate consent for residential conversion The Earls Court landowners map above is indicative. -

Lillie Road, West Brompton, SW6 £645 Per Week

Fulham 843 Fulham Road London SW6 5HJ Tel: 020 7731 7788 [email protected] lillie Road, West Brompton, SW6 £645 per week (£2,803 pcm) 4 bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms Preliminary Details A large four bedroom maisonette boasting high ceilings, period features and two bathrooms in West Brompton. This split level property is currently being decorated throughout. The flat is also conveniently located for the shops and bars of Fulham and Parsons Green, and minutes from the ever popular The Prince. The property is located within minutes of West Brompton Station which has access to both the Underground and National Rail services providing ample transport links in and out of London. It is also within easy reach Earls Court Underground Station which has access to the District and Piccadilly Lines. The property would be perfectly suited for professional or student sharers. Key Features • Spacious period conversion • Four large double bedrooms • Two Bathrooms • Dining room/reception room • Separate Kitchen • Close to West Brompton station Fulham | 843 Fulham Road, London, SW6 5HJ | Tel: 020 7731 7788 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview The area of West Brompton is served by both the tube and rail which offer direct access to Earls Court Exhibition Centre. Home to The Empress State Building, a skyscraper 328 ft tall built in tribute to the Empire State Building, the area has a lot to offer and is an enviable place to live. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations West Brompton (0.2M) West Brompton (0.2M) West Kensington (0.4M) Fulham | 843 Fulham -

The Rise of Leagues and Their Impact on the Governance of Women's Hockey in England

‘Will you walk into our parlour?’: The rise of leagues and their impact on the governance of women's hockey in England 1895-1939 Joanne Halpin BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: May 2019 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Jo Halpin to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature: …………………………………….. Date: ………………………………………….. Jo Halpin ‘Will you walk into our parlour?’ Doctoral thesis Contents Abstract i List of abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Introduction: ‘Happily without a history’ 1 • Hockey and amateurism 3 • Hockey and other team games 8 • The AEWHA, leagues and men 12 • Literature review 15 • Thesis aims and structure 22 • Methodology 28 • Summary 32 Chapter One: The formation and evolution of the AEWHA 1895-1910 – and the women who made it happen 34 • The beginnings 36 • Gathering support for a governing body 40 • The genesis of the AEWHA 43 • Approaching the HA 45 • Genesis of the HA