General Assembly Security Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Heritage Is the Physical Manifestation of a People's History

Witnessing Heritage Destruction in Syria and Iraq Cultural heritage is the physical manifestation of a people’s history and forms a significant part of their identity. Unfortunately, the destruction of that heritage has become an ongoing part of the conflict in Syria and Iraq. With the rise of ISIS and the increase of political instability, important cultural sites and irreplaceable collections are now at risk in these countries and across the region. Mass murder, systematic terror, and forced resettlement have always been tools of ethnic and sectarian cleansing. But events in Syria and Iraq remind us that the erasure of cultural heritage, Map of Syria and Iraq which removes all traces of a people from the landscape, is part of the same violent process. Understanding this loss and responding to it remain a challenge for us all. Exhibit credits: Smithsonian Institution University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology American Association for the Advancement of Science U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield A Syrian inspects a damaged mosque following bomb attacks by Assad regime forces in the opposition-controlled al-Shaar neighborhood of Aleppo, Syria, on September 21, 2015. Conflict in Syria and Iraq (Photo by Ibrahim Ebu Leys/Anadolu Agency/ Getty Images) Recent violence in Syria and Iraq has shattered daily life, leaving over 250,000 people dead and over 12 million displaced. Beginning in 2011, civil protests in Damascus and Daraa against the Assad government were met with a severe crackdown, leading to a civil war and creating a power vacuum within which terror groups like ISIS have flourished. -

Displaced Loyalties: the Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey

Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe Chad Hazlett Tolga Sinmazdemir Working Paper 18-024 Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe Harvard Business School Chad Hazlett UCLA Tolga Sinmazdemir Bogazici University Working Paper 18-024 Copyright © 2017 by Kristin Fabbe, Chad Hazlett, and Tolga Sinmazdemir Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe,∗ Chad Hazlett,y & Tolga Sınmazdemirz December 8, 2017 Abstract How does violence during conflict affect the political attitudes of civilians who leave the conflict zone? Using a survey of 1,384 Syrian refugees in Turkey, we employ a natural experiment owing to the inaccuracy of barrel bombs to examine the effect of having one's home destroyed on political and community loyalties. We find that refugees who lose a home to barrel bombing, while more likely to feel threatened by the Assad regime, are less supportive of the opposition, and instead more likely to say no armed group in the conflict represents them { opposite to what is expected when civilians are captive in the conflict zone and must choose sides for their protection. Respondents also show heightened volunteership towards fellow refugees. Altogether, this suggests that when civilians flee the conflict zone, they withdraw support from all armed groups rather than choosing sides, instead showing solidarity with their civilian community. -

The Reverberating Effects of Explosive Weapon Use in Syria Contents

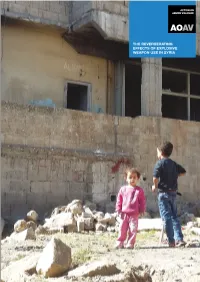

THE REVERBERATING EFFECTS OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPON USE IN SYRIA CONTENTS Introduction 4 1.1 Timeline 6 1.2 Worst locations 8 1.3 Weapon types 11 1.4 Actors 12 Health 14 Economy 19 Environment 24 Society and Culture 30 Conclusion 36 Recommendations 37 Report by Jennifer Dathan Notes 38 Additional research by Silvia Ffiore, Leo San Laureano, Juliana Suess and George Yaolong Editor Iain Overton Copyright © Action on Armed Violence (January 2019) Cover illustration Syrian children play outside their home in Gaziantep, Turkey by Jennifer Dathan Design and printing Tutaev Design Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome Research and publication funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 4 | ACTION ON ARMED VIOLENCE REVERBERATING EFFECTS OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS IN SYRIA | 5 INTRODUCTION The use of explosive weapons, particularly in populated noticed the following year that, whilst total civilian families from both returning to their homes and using areas, causes wide-spread and long-term harm to casualties (deaths and injuries) were just below that their land. Such impact has devastating and lingering civilians. Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) has been of the previous year, civilian deaths had increased by consequences for communities and cultures. monitoring casualties from the use of explosive 50% (from 5,639 in 2016 to 8,463 in 2017). As the war weapons around the globe since 2010. So extreme continued, injuries were increasingly less likely to be In this report, AOAV seeks to better understand the has such harm been in Syria in recent years that, recorded - particularly in incidents where there were reverberating harms from the explosive violence in by the end of 2017, Syria had overtaken Iraq as the high levels of civilian deaths. -

Evolution in Military Affairs in the Battlespace of Syria and Iraq

P. MARTON DOI: 10.14267/cojourn.2017v2n2a3 COJOURN 2:2-3 (2017) Evolution in military affairs in the battlespace of Syria and Iraq Péter Marton1 Abstract This paper will consider developments in the Syrian and Iraqi battlespaces that may be conceptualised as relevant to the broader evolution in military affairs. A brief discussion of different notions of „revolution" and „evolution” (in Military Affairs) will be offered, followed by an overview of the combatant actors involved in engagements in the battlespace concerned. The analysis distinguishes at the start between two different evolutionary processes: one specific to the local theatre of war in which local combatants, heavily constrained by their circumstances and limitations, show innovation with limited resources and means, and with very high (existential) stakes. This actually existential evolutionary process is complicated by the effects of the only quasi-evolutionary process of major powers’ interactions (with each other and with local combatants). The latter process is quasi-evolutionary in the sense that it does not carry direct existential stakes for the central players involved in it. The stakes are in a sense virtual: being a function of the prospects of imagined peer-competitor military conflict. Key cases studied in the course of the discussion include (inter alia) the evolution of the Syrian Arab Air Force's use of so-called barrel bombs as well as the use of land-attack cruise missiles and other high-end weaponry by major intervening powers. Keywords: RMA, warfare, militaries, tactics, strategy, Syria, Iraq Introduction: Evolution in military affairs Evolution, in the case of more complex organisms, is the combined effect of genetic re- combination and natural selection that results in the adaptation of different species to their 1 Péter Marton is Associate Professor at Corvinus University’s Institute of International Studies, and Editor- in-Chief of COJOURN. -

The Sudan Consortium the Impact of Sudanese Military Operations On

The Sudan Consortium African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan The impact of Sudanese military operations on the civilian population of Southern Kordofan1 April 2014 The Sudan Consortium works with a trusted group of local Sudanese partners who have been working on the ground in Southern Kordofan since the current conflict began in late 2011. All the attacks referred to in this report were launched against areas where there was no military presence and which were clearly identifiable as civilian in character. We believe that this information provides strong circumstantial evidence that civilians are being directly and deliberately targeted by the Sudanese armed forces in Southern Kordofan. In the last week of April, large numbers of civilians were reported to have been displaced from their homes in Delami County, South Kordofan as a result of a major new military offensive launched in Southern Kordofan by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). Although exact numbers are difficult to establish, partners have cited estimates between 45,000 and 70,000. The government offensive in Southern Kordofan appears to have been concentrated on Rashad, Al Abisseya and Delami counties in the north-east of Southern Kordofan. The situation on the ground remains fluid and information from Rashad and Al Abisseya counties has been difficult to obtain. However the Sudan Consortium’s partners on the ground have been able to report firsthand on the situation in Delami County and have interviewed internally displaced persons (IDPs) fleeing from the fighting further north. From 12 April onwards, several locations in Delami County, notably Aberi, Mardis and Sarafyi, were subject to heavy bombardment on a daily basis by artillery and multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS) deployed by the Sudanese Armed Forces. -

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice /STJ is a nonprofit, nongovernmental, independent Syrian organization. STJ includes many defenders and human rights defenders from Syria and from different backgrounds and affiliations, including academics of other nationalities. The organization works for Syria, where all Syrians, without discrimination, should be accorded dignity, justice and equal human rights. 1 Repeated Attacks with Incendiary Weapons, Cluster Munitions and Chemicals on Eastern Ghouta A Flash Report Documenting the events of 7 March 2018 in Hamoryah and those of 10 and 11 March 2018 in Irbin 2 Introduction Syrian regular forces and their allies continued their heaviest military campaign1 on Eastern Ghouta cities and towns, using various types of weapons, such as rocket launchers “Smerch type”, barrel bombs, guided missiles and incendiary weapons. As on March 7, 2018, the city of Hamoryah2 witnessed a bloody day (following adoption of Security Council Resolution No. 2401), where it was shelled with weapons loaded with incendiary substances, similar to phosphorous, and napalm-like substances. This was accompanied with targeting Hamoryah with a barrel bomb, loaded with toxic gas, dropped by a helicopter on the road between Saqba town and Hamoryah, as confirmed by the field researcher of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ. As well as targeting the city with a rocket loaded with cluster munitions the same day. This intensive shelling killed at least 29 civilians, two of whom were burnt to death with incendiary substances, and caused suffocation to scores of civilians as a result of using toxic gas besides the outbreak of fires in residential buildings The hysterical shelling hasn’t spared the city of Irbin3, which was targeted by chemical weapons loaded with incendiary substances similar to phosphorus and others loaded with napalm-like substances, on 10 and 11 March 2018. -

The Syrian Regime Has Dropped Nearly 70,000 Barrel Bombs on Syria the Ruthless Bombing

The Syrian Regime Has Dropped Nearly 70,000 Barrel Bombs on Syria The Ruthless Bombing Monday, December 25, 2017 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Report Contents I. Introduction and Methodology II. What are Barrel Bombs? III. Indiscriminate Barrel Bomb Attacks in Context of Military Progression IV. Use of Barrel Bombs before and after Security Council Resolution 2139 V. Use of Barrel Bombs since July 2012 VI. Most Notable Incidents of Barrel Bomb Use VII. Conclusions and Recommendations I. Introduction and Methodology The use of barrel bombs, which are dropped by the Syrian regime army from their heli- copters or fixed-wing warplanes, manifest one of the most appalling ways in which the international community has blatantly let down the Syrian people as these barrel bombs have been forgotten almost completely in the last year with no condemnations to be heard about the repeated use of this barbarian type of weapons which is a disgrace for any army in the modern world seeing that dropping a barrel loaded with explosive objects from an altitude as high as 5,000 meters rely mainly on the principle of free falling and air currents. This strategy should have been condemned by military men from around the world. Using this rudimentary weapon against civilians in this repeated fashion fully reflects the unprec- edented degeneration that the army institution of the ruling regime has fallen into just to kill and exterminate the Syrian people. -

Iraqi Government Accused of Barrel Bombing ISIS-Held Falluja

2 July 10, 2015 News & Analysis Iraq Iraqi government accused of barrel bombing ISIS-held Falluja Omar Hejab a city block, constitutes a war crime. Falluja residents said barrel Baghdad bombs were dropped there after Iraqi lawmaker Qassem al-Aaraji he Iraqi Air Force dropped labelled the city the “head of deadly barrel bombs on the snake”. He told parliament the Islamic State-held city on June 2nd, “All the population of Falluja, killing dozens there is affiliated with ISIS (an Is- of people and wounding lamic State acronym) and should Tmore than 200, Sunni tribal leaders, be wiped out totally.” residents and medical officials said. According to YouTube videos Medical officials at a Falluja posted by activists, the Shia-dom- hospital said at least 79 people, inated Iraqi government has used including 20 children and nine barrel bombs against several cit- women, were killed, and 212 oth- ies in its war against ISIS, which ers wounded in barrel bomb at- controls about one-third of the tacks that began June 18th and country. Mosul, Taiji and Tikrit, all continued through early July. battlefronts in the war against ISIS The makeshift bombs — oil since mid-2014, have been hit sev- drums packed with explosives and eral times. shrapnel — have killed or wounded Activists say the home-made thousands of Syrians since the em- bombs are usually dropped at battled regime of President Bashar night to evade being recorded on Assad began using them in 2012. video. Iraq’s Shia paramilitaries launch a rocket towards Islamic State militants north of Falluja in Anbar On June 1st, Sunni tribal lead- province, July 6, 2015. -

The Use of Barrel Bombs and Indiscriminate Bombardment in Syria: the Need to Strengthen Compliance with International Humanitarian Law

The use of barrel bombs and indiscriminate bombardment in Syria: the need to strengthen compliance with international humanitarian law Statement by Mr. Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Chair of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic Presented at a side event hosted by the Permanent Mission of Austria and Article 36 Geneva, 12 March 2015 Mr. Ambassador, Distinguished Members of the panel, Ladies and Gentlemen, Since 2012, indiscriminate and disproportionate bombardments have been the primary cause of civilian casualties and mass displacement in the Syrian Arab Republic. A significant portion of documented civilian casualties have resulted from the use of explosive devices against targets located within densely populated areas. According to NGOs working on documentation, casualties from aerial strikes, ground shelling and explosions count for over 50% of total documented deaths in 2014, a substantial part of which are caused by barrel bombs. Indiscriminate bombardments have also damaged homes, medical facilities, schools, water and electrical facilities, bakeries and crops. In many cases, shelling was conducted in support of on-going sieges imposed on restive localities and neighbourhoods, in particular by State forces in areas like Yarmouk camp in Damascus and Al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs city. Despite their largely different scales of involvement, all parties to the Syrian civil war, with no exception, have used heavy weaponry in their possession to target populated areas leading to civilian casualties. It is partly due to the fact that most active frontlines have been located inside urban centres where fighters of all belligerents have continued to operate among civilians, putting their lives at risk. -

Download (PDF)

N° 03/2017 recherches & documents mai 2017 The Shayrat Connection: Was the Khan Shaykun Chemical Attack Inevitable but Preventable? CAN KASAPOGLU WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-911101-96-0 EAN : 9782911101960 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 BRIEF TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE KHAN SHAYKUN ATTACK ............................................ 6 THE CHEMICAL BLITZ .............................................................................................................. 8 THE REGIME’S TOP CHAIN OF COMMAND: MANAGING THE CHEMICAL WARFARE CAPABILITIES .. 9 MILITARY GEOSTRATEGIC CONTEXT OF THE CW USE IN SYRIA ................................................10 CARRYING OUT THE DIRTY JOB: TACTICAL LINK OF THE WMD CHAIN ......................................14 THE SUSPECTED AIR FORCE LINK ..........................................................................................14 CALLING IN THE CHEMICAL STRIKE .........................................................................................15 CONCLUSION .........................................................................................................................18 -

The War Report Armed Conflicts in 2016

THE WAR REPORT ARMED CONFLICTS IN 2016 ANNYSSA BELLAL THE ACADEMY A JOINT CENTER OF THE WAR REPORT ARMED CONFLICTS IN 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The War Report 2016 was written by Dr Annyssa Bellal, Strategic Adviser on In- ternational Humanitarian Law and Research Fellow at the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights (Geneva Academy), with the research assistance of Shashaank Bahadur Nagar, LLM 2016, Geneva Academy. The War Report 2016 also builds on the work of the past editions of 2012, 2013 (edited by Stuart Casey-Maslen) and 2014 (edited by Annyssa Bellal). The Geneva Academy would like to thank the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) for its support to the research on this issue. DISCLAIMER This report is the work of the author. The views expressed in it do not necessarily reflect those of the Geneva Academy. The qualification of any situation of armed violence as an armed conflict under international law should not be read such as to trigger war clauses in insurance contracts and does not in any way affect the need for due diligence by any natural or legal person in their work in any of the situa- tions referred to. Furthermore, facts, matters, or opinions contained in the report are provided by the Geneva Academy without assuming responsibility to any user of the report who may rely on its contents in whole or in part. The designation of armed non-state actors, states, or territories does not imply any judgement by the Geneva Academy regarding the legal status of such actors, states, or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or the delimitation of their boundaries, or the status of any states or territories that border them. -

360 Syria Faq Sheet

360 SYRIA FAQ SHEET VIRTUAL REALITY IN SYRIA Useful background info for talking points. 1. What are barrel bombs? There are different types, but the usual barrel bomb is usually an oil drum filled with TNT and shrapnel that has been pushed out of a helicopter from high altitude. These weapons cannot be targeted, and they explode on contact. o Residents told us they were the most afraid of these weapons – usually they can see them falling through the air, and there is a specific hissing noise. You are talking about a barrel that is literally tumbling through the air, so residents have about 2 minutes to run. o Residents told us repeatedly that they didn’t know where to run. o An aid worker said he had accepted multiple cases in Turkey involving the loss of hearing from the explosions, especially from young children. 2. What is the civilian impressions of barrel bombs? o Intense fear – top concern for Aleppo residents (2 minutes of waiting to die as they watch the barrel tumble through the air) o “Double-tap” strikes – second barrel bomb dropped on the same location, up to 30 minutes after the first one. The second strike often kills rescue workers, neighbours, or family members who come to help. o Horrific injuries – doctor said he had been dealing with injuries he hadn’t seen in any medical book. The scenes described and can been seen in videos and photos, with bodies in pieces, intestines out of bodies, etc. 360 SYRIA: INFORMATION SHEET 3. What is a crime against humanity? o A crime against humanity is one of the most serious violations of international law.