Video Activists from Aleppo and Raqqa As ‘Modern-Day Kinoks’? an Audiovisual Narrative of the Syrian Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deir-Ez-Zor Governorate - Gender-Based Violence Snapshot, January - June 2016

Deir-ez-Zor Governorate - Gender-Based Violence Snapshot, January - June 2016 Total Population: 0.94 mio No. of Sub-Districts: 14 Total Female Population: 0.46 mio No. of Communities: 133 Total Population > Age of 18: 0.41 mio No. of Hard-to-Reach Locations: 133 IDPs: 0.32 mio No. of Besieged Locations: 0 People in Need: 0.75 mio GOVERNORATE HIGHLIGHTS & CAPACITY BUILDING INITIATIVES: Ar-Raqqa P ! • Several GBV training sessions were provided in Basira, Kisreh and Sur ! sub-districts Kisreh Tabni Sur Deir-ez-Zor P Deir-ez-Zor Khasham Basira NUMBER OF ORGANIZATIONS BY ACTIVITY IN EACH SUB-DISTRICT Awareness Raising Dignity Kits Distribution Psychosocial Support IRAQIRAQ Skills Building & Livelihoods Specialised Response Muhasan Thiban P Governorate Capitals Governorate Boundaries Al Mayadin District Boundaries Sub-District Boundaries Hajin Ashara GBV Reach !1 -!>5 Women and Girls Safe Spaces (Jun 2016) 1 1 1 !1 - >5 Women and Girls Safe Spaces (Jan-May 2016) Jalaa ! Areas of Influence (AoI) Syria Susat Contested Areas Golan Heights Abu Kamal Government (SAA) ´ ISIS-affiliated groups A S H A R A D E I R - E Z - Z O R M U H A S A N Kurdish Forces NUMBER OF ORGANIZATIONS BY HUB IN EACH SUB -DISTRICT Non-state armed groups and ANF Amman Hub Damascus Hub Gaziantep Hub Unspecified Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsment. This map is based on available data 0 12.5 25 50 km at sub-district level only. Information visualized on this map is not to be considered complete or geographically correct. -

Local Elections: Is Syria Moving to Reassert Central Control?

RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019/03 RESEARCH PROJECT LOCAL REPORT ELECTIONS: IS JUNE 2016 SYRIA MOVING TO REASSERT CENTRAL CONTROL? AUTHORS: AGNÈS FAVIER AND MARIE KOSTRZ © European University Institute,2019 Content© Agnès Favier and Marie Kostrz, 2019 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions, Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/03 February 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Local elections: Is Syria Moving to Reassert Central Control? Agnès Favier and Marie Kostrz1 1 Agnès Favier is a Research Fellow at the Middle East Directions Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. She leads the Syria Initiative and is Project Director of the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project. Marie Kostrz is a research assistant for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project at the Middle East Directions Programme. This paper is the result of collective research led by the WPCS team. 1 Executive summary Analysis of the local elections held in Syria on the 16th of September 2018 reveals a significant gap between the high level of regime mobilization to bring them about and the low level of civilian expectations regarding their process and results. -

Ar-Raqqa (Household Surveys) August 2018

Syria Shelter and NFI Assessment: Ar-Raqqa (Household Surveys) August 2018 CONTEXT AND METHODOLOGY Map 1: Sub-districts assessed Since the conflict in Ar-Raqqa city ended in October 2017, access to the city and the governorate has increased, however, remains challenging due to the prevalence of unexploded ordnance.1 The removal of contaminated soil in Ar-Raqqa governorate started in June 2018, but significant challenges persist. Displacement in the governorate is likely to be protracted as individuals return to their community origin, regardless of the security challenges. To provide up-to-date information on shelter conditions and NFI availability and affordability across northern Syria, REACH conducted an assessment on behalf of the Shelter and NFI Cluster and in partnerships with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Findings presented in this factsheet are based on data collected between 24 June and 2 August 2018 from a total of 819 households across 89 communities and 7 sub-districts in Ar-Raqqa governorate. Households were sampled to allow findings to be generalisable with a 95% level of confidence and 10% margin of error at the sub-district level, and at least the same level of confidence and margin of error at the regional level. This factsheet also refers to data from a similar assessment from July 2017 in order to highlight significant trends.2 KEY FINDINGS This assessment found that a high proportion of Spontaneous returnees’ (SRs) last place of departure was within Ar-Raqqa governorate (92%). 90% of SR households in the governorate reported property ownership as the primary reason for returning to their community of origin. -

Cultural Heritage Is the Physical Manifestation of a People's History

Witnessing Heritage Destruction in Syria and Iraq Cultural heritage is the physical manifestation of a people’s history and forms a significant part of their identity. Unfortunately, the destruction of that heritage has become an ongoing part of the conflict in Syria and Iraq. With the rise of ISIS and the increase of political instability, important cultural sites and irreplaceable collections are now at risk in these countries and across the region. Mass murder, systematic terror, and forced resettlement have always been tools of ethnic and sectarian cleansing. But events in Syria and Iraq remind us that the erasure of cultural heritage, Map of Syria and Iraq which removes all traces of a people from the landscape, is part of the same violent process. Understanding this loss and responding to it remain a challenge for us all. Exhibit credits: Smithsonian Institution University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology American Association for the Advancement of Science U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield A Syrian inspects a damaged mosque following bomb attacks by Assad regime forces in the opposition-controlled al-Shaar neighborhood of Aleppo, Syria, on September 21, 2015. Conflict in Syria and Iraq (Photo by Ibrahim Ebu Leys/Anadolu Agency/ Getty Images) Recent violence in Syria and Iraq has shattered daily life, leaving over 250,000 people dead and over 12 million displaced. Beginning in 2011, civil protests in Damascus and Daraa against the Assad government were met with a severe crackdown, leading to a civil war and creating a power vacuum within which terror groups like ISIS have flourished. -

Displaced Loyalties: the Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey

Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe Chad Hazlett Tolga Sinmazdemir Working Paper 18-024 Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe Harvard Business School Chad Hazlett UCLA Tolga Sinmazdemir Bogazici University Working Paper 18-024 Copyright © 2017 by Kristin Fabbe, Chad Hazlett, and Tolga Sinmazdemir Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe,∗ Chad Hazlett,y & Tolga Sınmazdemirz December 8, 2017 Abstract How does violence during conflict affect the political attitudes of civilians who leave the conflict zone? Using a survey of 1,384 Syrian refugees in Turkey, we employ a natural experiment owing to the inaccuracy of barrel bombs to examine the effect of having one's home destroyed on political and community loyalties. We find that refugees who lose a home to barrel bombing, while more likely to feel threatened by the Assad regime, are less supportive of the opposition, and instead more likely to say no armed group in the conflict represents them { opposite to what is expected when civilians are captive in the conflict zone and must choose sides for their protection. Respondents also show heightened volunteership towards fellow refugees. Altogether, this suggests that when civilians flee the conflict zone, they withdraw support from all armed groups rather than choosing sides, instead showing solidarity with their civilian community. -

The Reverberating Effects of Explosive Weapon Use in Syria Contents

THE REVERBERATING EFFECTS OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPON USE IN SYRIA CONTENTS Introduction 4 1.1 Timeline 6 1.2 Worst locations 8 1.3 Weapon types 11 1.4 Actors 12 Health 14 Economy 19 Environment 24 Society and Culture 30 Conclusion 36 Recommendations 37 Report by Jennifer Dathan Notes 38 Additional research by Silvia Ffiore, Leo San Laureano, Juliana Suess and George Yaolong Editor Iain Overton Copyright © Action on Armed Violence (January 2019) Cover illustration Syrian children play outside their home in Gaziantep, Turkey by Jennifer Dathan Design and printing Tutaev Design Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome Research and publication funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 4 | ACTION ON ARMED VIOLENCE REVERBERATING EFFECTS OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS IN SYRIA | 5 INTRODUCTION The use of explosive weapons, particularly in populated noticed the following year that, whilst total civilian families from both returning to their homes and using areas, causes wide-spread and long-term harm to casualties (deaths and injuries) were just below that their land. Such impact has devastating and lingering civilians. Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) has been of the previous year, civilian deaths had increased by consequences for communities and cultures. monitoring casualties from the use of explosive 50% (from 5,639 in 2016 to 8,463 in 2017). As the war weapons around the globe since 2010. So extreme continued, injuries were increasingly less likely to be In this report, AOAV seeks to better understand the has such harm been in Syria in recent years that, recorded - particularly in incidents where there were reverberating harms from the explosive violence in by the end of 2017, Syria had overtaken Iraq as the high levels of civilian deaths. -

Situation Overview Key Figures

Turkey | Syria: Humanitarian Dashboard - Cross Border Response Jan-Mar 2016 (Issued on 04 May 2016) SITUATION OVERVIEW Conflict between non-state armed opposition groups (NSAOGs), the Islamic State and Government of Syria continued during most of the first quarter of 2016, resulting in various impediments to humanitarian programming across Syria. Most notably, in the months of January and February, GoS and allies intensified attacks on civilian infrastructure, including medical facilities, schools, IDP camps, bakeries and humanitarian warehouses, stymieing humanitarian access to many vulnerable communities across Syria. This in attacks resulted in even more communities being displaced from the Northern Aleppo countryside and elsewhere in Northern Latakia. By the end of February, a ‘cessation of hostilities’ agreement brokered by the US and Russia came into effect, resulting in significant reduction in hostilities between NSAOGs and the GoS across most of Syria, allowing more access to displaced communities for many humanitarian agencies in Aleppo, Idleb, Latakia and Hama. Despite a reduction in violence, isolated incidents have continued in key areas around access routes into Aleppo City between Kurdish forces and NSAOGs, leading to intermittent impediments along the Castello Road supply route. In eastern Syria, air strikes continued to impact civilian infrastructure under ISIL control, resulting in further degradation of hospitals, as well as vital electricity and water networks in Raqqa and Aleppo governorates. Under UNSC resolution 2165/2258, UN and its partners sent 41 consignments from Turkey (16 from Bab al-Salam - BAS, 25 from Bab al-Hawa- BAH) to the Syrian Arab Republic consisting of 1,341 trucks. 1,130 of these trucks used the BAH border crossing while the remaining 211 crossed from BAS border crossing. -

Evolution in Military Affairs in the Battlespace of Syria and Iraq

P. MARTON DOI: 10.14267/cojourn.2017v2n2a3 COJOURN 2:2-3 (2017) Evolution in military affairs in the battlespace of Syria and Iraq Péter Marton1 Abstract This paper will consider developments in the Syrian and Iraqi battlespaces that may be conceptualised as relevant to the broader evolution in military affairs. A brief discussion of different notions of „revolution" and „evolution” (in Military Affairs) will be offered, followed by an overview of the combatant actors involved in engagements in the battlespace concerned. The analysis distinguishes at the start between two different evolutionary processes: one specific to the local theatre of war in which local combatants, heavily constrained by their circumstances and limitations, show innovation with limited resources and means, and with very high (existential) stakes. This actually existential evolutionary process is complicated by the effects of the only quasi-evolutionary process of major powers’ interactions (with each other and with local combatants). The latter process is quasi-evolutionary in the sense that it does not carry direct existential stakes for the central players involved in it. The stakes are in a sense virtual: being a function of the prospects of imagined peer-competitor military conflict. Key cases studied in the course of the discussion include (inter alia) the evolution of the Syrian Arab Air Force's use of so-called barrel bombs as well as the use of land-attack cruise missiles and other high-end weaponry by major intervening powers. Keywords: RMA, warfare, militaries, tactics, strategy, Syria, Iraq Introduction: Evolution in military affairs Evolution, in the case of more complex organisms, is the combined effect of genetic re- combination and natural selection that results in the adaptation of different species to their 1 Péter Marton is Associate Professor at Corvinus University’s Institute of International Studies, and Editor- in-Chief of COJOURN. -

UK Home Office

Country Policy and Information Note Syria: the Syrian Civil War Version 4.0 August 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

The Sudan Consortium the Impact of Sudanese Military Operations On

The Sudan Consortium African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan The impact of Sudanese military operations on the civilian population of Southern Kordofan1 April 2014 The Sudan Consortium works with a trusted group of local Sudanese partners who have been working on the ground in Southern Kordofan since the current conflict began in late 2011. All the attacks referred to in this report were launched against areas where there was no military presence and which were clearly identifiable as civilian in character. We believe that this information provides strong circumstantial evidence that civilians are being directly and deliberately targeted by the Sudanese armed forces in Southern Kordofan. In the last week of April, large numbers of civilians were reported to have been displaced from their homes in Delami County, South Kordofan as a result of a major new military offensive launched in Southern Kordofan by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). Although exact numbers are difficult to establish, partners have cited estimates between 45,000 and 70,000. The government offensive in Southern Kordofan appears to have been concentrated on Rashad, Al Abisseya and Delami counties in the north-east of Southern Kordofan. The situation on the ground remains fluid and information from Rashad and Al Abisseya counties has been difficult to obtain. However the Sudan Consortium’s partners on the ground have been able to report firsthand on the situation in Delami County and have interviewed internally displaced persons (IDPs) fleeing from the fighting further north. From 12 April onwards, several locations in Delami County, notably Aberi, Mardis and Sarafyi, were subject to heavy bombardment on a daily basis by artillery and multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS) deployed by the Sudanese Armed Forces. -

In PDF Format, Please Click Here

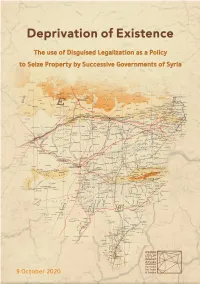

Deprivatio of Existence The use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria A special report sheds light on discrimination projects aiming at radical demographic changes in areas historically populated by Kurds Acknowledgment and Gratitude The present report is the result of a joint cooperation that extended from 2018’s second half until August 2020, and it could not have been produced without the invaluable assistance of witnesses and victims who had the courage to provide us with official doc- uments proving ownership of their seized property. This report is to be added to researches, books, articles and efforts made to address the subject therein over the past decades, by Syrian/Kurdish human rights organizations, Deprivatio of Existence individuals, male and female researchers and parties of the Kurdish movement in Syria. Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) would like to thank all researchers who contributed to documenting and recording testimonies together with the editors who worked hard to produce this first edition, which is open for amendments and updates if new credible information is made available. To give feedback or send corrections or any additional documents supporting any part of this report, please contact us on [email protected] About Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) STJ started as a humble project to tell the stories of Syrians experiencing enforced disap- pearances and torture, it grew into an established organization committed to unveiling human rights violations of all sorts committed by all parties to the conflict. Convinced that the diversity that has historically defined Syria is a wealth, our team of researchers and volunteers works with dedication at uncovering human rights violations committed in Syria, regardless of their perpetrator and victims, in order to promote inclusiveness and ensure that all Syrians are represented, and their rights fulfilled. -

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice /STJ is a nonprofit, nongovernmental, independent Syrian organization. STJ includes many defenders and human rights defenders from Syria and from different backgrounds and affiliations, including academics of other nationalities. The organization works for Syria, where all Syrians, without discrimination, should be accorded dignity, justice and equal human rights. 1 Repeated Attacks with Incendiary Weapons, Cluster Munitions and Chemicals on Eastern Ghouta A Flash Report Documenting the events of 7 March 2018 in Hamoryah and those of 10 and 11 March 2018 in Irbin 2 Introduction Syrian regular forces and their allies continued their heaviest military campaign1 on Eastern Ghouta cities and towns, using various types of weapons, such as rocket launchers “Smerch type”, barrel bombs, guided missiles and incendiary weapons. As on March 7, 2018, the city of Hamoryah2 witnessed a bloody day (following adoption of Security Council Resolution No. 2401), where it was shelled with weapons loaded with incendiary substances, similar to phosphorous, and napalm-like substances. This was accompanied with targeting Hamoryah with a barrel bomb, loaded with toxic gas, dropped by a helicopter on the road between Saqba town and Hamoryah, as confirmed by the field researcher of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ. As well as targeting the city with a rocket loaded with cluster munitions the same day. This intensive shelling killed at least 29 civilians, two of whom were burnt to death with incendiary substances, and caused suffocation to scores of civilians as a result of using toxic gas besides the outbreak of fires in residential buildings The hysterical shelling hasn’t spared the city of Irbin3, which was targeted by chemical weapons loaded with incendiary substances similar to phosphorus and others loaded with napalm-like substances, on 10 and 11 March 2018.