Zvanu3tics PMMT OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

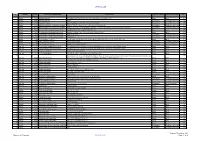

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Draft Outline

Tunisia Resilience and Community Empowerment Activity Quarterly Report Year Two, Quarter One – October 1, 2019 – December 30, 2019 Submission Date: January 30, 2019 Agreement Number: 72066418CA00001 Activity Start Date and End Date: SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 to AUGUST 31, 2023 AOR Name: Hind Houas Submitted by: Nadia Alami, Chief of Party FHI360 Tanit Business Center, Ave de la Fleurs de Lys, Lac 2 1053 Tunis, Tunisia Tel: (+216) 58 52 56 20 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. July 2008 1 Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... ii 1. Project Overview/ Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Project Description ........................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Analysis of Overall Program Progress Toward Results .................................................................... 4 2. Summary of Activities Conducted ............................................................................................................ 12 2.1 Objective 1: Strengthened Community Resilience ........................................................................... 12 RESULT 1.1: COMMUNITY MEMBERS, IN PARTICULAR MARGINALIZED GROUPS, DEMONSTRATE AN ENHANCED LEVEL OF ENGAGEMENT, -

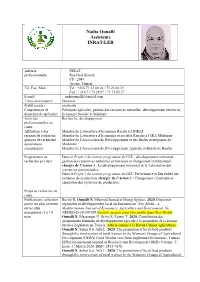

Nadia Ounalli Assistante INRAT/LER

Nadia Ounalli Assistante INRAT/LER Adresse INRAT, professionnelle Rue Hedi Karray CP : 2049 Ariana, Tunisia Tel, Fax, Mob. Tel : +216 71 23 00 24 / 71 23 02 39 Fax : +216 71 75 28 97 / 71 71 65 37 E-mail [email protected] Titres universitaire Doctorat Statut (grade) assistante Compétences et Politiques agricoles, gestion des ressources naturelles, développement territorial, domaines de spécialité Economie Sociale et Solidaire Activités Recherche, développement professionnelles en cours Affiliation à des Membre du Laboratoire d’Economie Rurale à l’INRAT réseaux de recherche, Membre du Laboratoire d’Economie et sociétés Rurales à l’IRA Médenine groupes de recherche, Membre de l’Association de Développement et des études stratégiques de associations Médenine scientifiques Membre de l’Association de Développement Agricole et Rurale de Haidra Programmes de Dans le Projet 3 du contrat programme du LER : développement territorial, recherche en cours gestion des ressources naturelles et foncières et changement institutionnel, chargée de l’Action 3 : Le développement territorial et la valorisation des ressources patrimoniales. Dans le Projet 2 du contrat programme du LER: Performance et Durabilité des systèmes de production, chargée de l’Action 3 : Changement climatique et adaptation des systèmes de production. Projet de recherche en cours Publications (sélection Bechir R, Ounalli N. Mhemed Jaoued et Mongi Sghaier, 2020. Disparités parmi les plus récentes régionales et développement local au Sud tunisien. New Medit - A ou les plus Mediterranean Journal of Economics, Agriculture and Environment. No. marquantes) 5 à 10 NEMED-D-20-00010R1(article accepté pour être publié dans New Medit) max Ounalli N, Marzougui N, Selmi S, Fazeni T, 2020. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Integrated rural development a case study of monastir governorate Tunisia Harrison, Ian C. How to cite: Harrison, Ian C. (1982) Integrated rural development a case study of monastir governorate Tunisia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9340/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk INTEGRATED RURAL DEVELOPMENT A CASE STUDY OP MONASTIR GOVERNORATE TUNISIA IAN C. HARRISON The copyright of this thesis tests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without bis prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD, Department of Geography, University of Durham. March 1982. ABSTRACT The Tunisian government has adopted an integrated rural development programme to tackle the problems of the national rural sector. The thesis presents an examination of the viability and success of the programme with specific reference to the Governorate of Monastir. -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

WFP Tunisia and Morocco Country Brief Donors September 2018 Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS)

WFP Tunisia and Morocco Country Brief In Numbers September 2018 US$1.6 m allocated by the Tunisian Government for the construction and equipment of two pilot kitchens WFP provides capacity-strengthening activities aimed at enhancing government-run National School Meals Programme The National School Meals Programme reach 250,000 children (120,000 girls and 130,000 boys) in Tunisia; and 1.4 m children (660,000 girls and 740,000 boys) in Morocco Operational Context Operational Updates Tunisia has undergone significant changes following the Jasmine Revolution of January 2011. The strategic direction Tunisia: of the Government currently focuses on strengthening • WFP continues to support the Ministry of Education in democracy, while laying the groundwork for a stronger setting up a pilot central kitchen, which will provide economic recovery. Tunisia has a GNI per capita of USD daily meals to 1,500 children in the hub school and 11,250 purchasing power parity (World Bank, 2015). The five satellite schools in the Nadhour district of the 2016 UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) ranks Tunisia Zaghouan governorate. The construction works for 97 out 188 countries and 58 on the Gender Inequality the central kitchen were completed, and the Index (GII 2015). equipment is being installed – both infrastructure and equipment were fully funded by the Government. Morocco is a middle-income, yet food-deficit country Also, upgrade works in two satellite schools have where the agricultural production fluctuates yearly as a started using government resources, while the result of weather variations and relies heavily on remaining three schools to be assessed and international markets to meet its consumption needs. -

Decree No. 2007-403 of February 26, 2007, on Amendments to Decree

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND MINISTRY OF EQUIPMENT, HOUSING WATER RESOURCES AND TERRITORIAL DEVELOPMENT Decree n° 2007-407 dated 26 February 2007, amending Decree n° 2007-403 dated 26 February 2007, amending decree n° 2000-1467 dated 20 June 2000, expropriating for decree n°2000-102 dated 18 January 2000, fixing the public purpose for the benefit of the housing land agency, composition and the functioning methods of the technical parcels of lands located in Ain Zaghouan governorate of commission for seeds , seedlings and plant varieties. Tunis, to develop a housing and equipments zone The President of the Republic, (Published only in Arabic and French). On a proposal from the Minister of Agriculture and Water Resources, Decree n°2007-408 dated 26 February 2007, creating an Having regard to law n° 99-42 dated 10 May 1999, relating to objective-oriented management unit to achieve projects seeds, seedlings and new plant varieties, and notably article 6, of protection against floods in Ariana North, and the plain of Kairouan, and fixing its organization and Having regard to decree n° 2000-102 dated 18 January 2000, functioning methods fixing the composition and the functioning methods of the (Published only in Arabic and French). technical commission for seeds , seedlings and plant varieties, as amended by decree n° 2004-2322 dated 27 September 2004, Decree n° 2007-409 dated 26 February 2007, approving the Having regard to decree n°2001-420 dated 13 February review of the urban development plan of the commune of 2001, fixing the organization of the Ministry of Agriculture, Ghardimaou (governorate of Jendouba). -

(Pdpfa- Gz) Country : Tunisia E

REPUBLIQUE TUNISIENNE MINISTERE DE L’INVESTISSEMENT ET DE LA COOPERATION INTERNATIONALE MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE, DES RESSOURCES HYDRAULIQUES ET DE LA PECHE Commissariat Régional de Développement Agricole de Zaghouan PROJECT : AGRICULTURAL SUBSECTOR DEVELOPMENT AND PROMOTION PROJECT IN ZAGHOUAN GOVERNORATE (PDPFA- GZ) COUNTRY : TUNISIA ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) SUMMARY May 2019 1 SUMMARY OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) Project Name : Agricultural Subsector Development and Promotion Project in Zaghouan Governorate (PDPFA-GZ) Country : TUNISIA 1. INTRODUCTION At the request of the Tunisian authorities, the African Development Bank Group will support the implementation of the Agricultural Subsector Development and Promotion Project in Zaghouan Governorate (PDPFA-GZ) in Tunisia. In accordance with the Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System, from an environmental and social standpoint, the project is classified in Category 2 in view of the negative environmental and social impacts identified, which are of low-to-moderate significance. In accordance with Tunisian law concerning environmental and social safeguards, an Environmental and Social Impact Notice and Environmental and Social Impact Plan have been produced. They have to be validated by the National Environmental Protection Agency (ANPE). Since the project affects people, property and livelihoods, a Framework Resettlement Action Plan (FRAP) was also produced pending finalisation of the definitive technical studies prior to works implementation. This document presents a summary of the PDPFA-GZ ESMP. The summary was prepared in compliance with AfDB’s Environmental and Social Assessment Guidelines and Procedures for Category 2 projects. 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1 Project Objectives PDPFA-GZ’s overall objective is to reduce poverty, unemployment and inequality (gender, socio-economic and rural-urban) in Zaghouan Governorate. -

Template for Unops Monthly Reports

Information Management & Mine Action Programs MONTHLY REPORT Month Covered in this Report: April 2017 (Period: 1st – 30th April 2017) Consultant Name: Badabate Diwediga Organization: Information Management and Mine Action Program Mailing Address: iMMAP, Jordan Office Date: 08 May 2017 Title: Impact evaluation of SLM options to achieve land degradation neutrality in Tunisia A. OBJECTIVES COMPLETED FOR LAST MONTH - OVERVIEW During the month of April (1st to 30 April 2017), under the supervision of Dr. Quang Bao Le (Systems- and GIS-based Sustainable Land Management – SLM, at ICARDA Amman), Mr. Enrico Bonaiuti (Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning – MEL, ICARDA Amman) and Mr. Victor Kimathi (iMMAP, Jordan Office), different tasks were performed following the objectives below: During this month (April 2017), focus was given to the following objectives: 1. Map the SLM options by context with their characteristics across Tunisia. The focus was to provide the spatial distribution of 19 SLM options identified for Tunisia so far. 2. Pursue the review the literature on SLM in Tunisia in order to update the database continuously. The database is continuously consolidated and progressively being finalised as the data are gathered and documented. B. OVERVIEW OF PROGRESS IN GIS-BASED SLM OxC DATA DEVELOPMENT The table 1 below provides an overview of the SLM being mapped in the two sites (Zaghouan and Medenine). SLM Technique References Socio- Land Use Name of documented of Name of visual file of the SLM ID Agricultural System the SLM OxC template OxC (syntax: <technique>_<SAEZ Ecological Zone (LUS) (if the (syntax: code>_<ALUS code>_<short name (SAEZ) (if the SLM is <technique>_<SAEZ of documenter>.zip; zip file SLM is selected, selected, code>_<ALUS includes: 5 files of GIS shape + a then write the then write code>_<short name of Google Earth image of an example relevant code in the relevant documenter>.xlsm) site in jpg + 1-2 field photos in jpg ANNEX 1 code in + a technical sketch of the ANNEX 2 technique in jpg) 1. -

Framework Resettlement Action Plan (Frap) Summary

REPUBLIQUE TUNISIENNE MINISTERE DE L’INVESTISSEMENT ET DE LA COOPERATION INTERNATIONALE MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE, DES RESSOURCES HYDRAULIQUES ET DE LA PECHE Commissariat Régional de Développement Agricole de Zaghouan PROJECT : AGRICULTURAL SUBSECTOR DEVELOPMENT AND PROMOTION PROJECT IN THE ZAGHOUAN GOVERNORATE (PDPFA-GZ) COUNTRY : TUNISIA FRAMEWORK RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (FRAP) SUMMARY May 2019 FRAMEWORK RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (FRAP) Project Name : Agricultural Subsector Development and Promotion Project in the Zaghouan Governorate (PDPFA-GZ) Country : TUNISIA 1. INTRODUCTION At the request of the Tunisian Authorities, the African Development Bank Group will support the implementation of the Agricultural Subsector Development and Promotion Project in the Zaghouan Governorate (PDPFA-GZ) in Tunisia. From an environmental and social standpoint, the project is classified in Category 2 in view of the negative environmental and social impacts identified, which are of low-to-moderate significance. It has become apparent that the project’s implementation will result in: (i) loss of property or restricted access to property; (ii) loss of sources of income or means of livelihood because of the project, which may or may not result in affected people leaving their land. Consequently, CRDA is obliged to initiate a process to acquire the necessary land by expropriation for public purposes to comply with Operational Safeguard 2 (OS2,) of the Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) on involuntary resettlement land acquisition, (land acquisitions, population displacement and compensation). At this stage, while the right-of-way is inherent in the construction of the different items of infrastructure planned, it is clear that the engineering designs prepared did not take into account aspects relating to the clearing of the rights-of-way to implement the planned works and the possible risk of expropriation. -

ICARDA Presentation

Standardised Database on Sustainable Land Management (SLM) Practices in the Governorates of Zaghouan and Medenine (Tunisia) Final Workshop “Sustainable Land Management to Achieve Land Degradation Badabate Diwediga (iMMAP) Neutrality: Options-by-Context Approach Quang Bao Le (ICARDA) and Tools” 24 October 2017 Taouffik Hermassi (INRGREF) Tunis, Tunisia Mohamed Ouessar (IRA Medenine) PRESENTATION OUTLINE 1. Context 2. Database generation • Mapping approach (Data sources & tools) • Process of metadata generation • Database and harmonisation 3. Results • Preliminar database • Harmonised and synthetised database • Data submission to GeOC platform 4. Conclusions, Limitations & Perspectives 5. Acknowledgements CONTEXT • Achieving SDG, especially the Target SDG 15.3 (Land Degradation Neutral-world by 2030), requires efforts for investing in Sustainable Land Management (SLM) at different scales, • Important is the need for spatially-explicit data on SLM efforts at national, regional, and local scales, developed based on standardised approaches and tools, and continuously consolidated in global monitoring systems • One of these innovative system-based tools contributing to the global efforts towards the SDG achievement is the Global Geo-informatics Options by Context (GeOC) CONTEXT • Global Geo-informatics Option by Context (GeOC), a tool for visualisation and contextualised analysis of SLM options at global level, has two main components: Sustainable Land Web-based GIS Management (SLM) Matched • Contextual Drivers of SLM • Standardized Synchronized -

Improving Dissemination Strategies to Increase Technology Adoption by Smallholders in the Tunisian Arid

TECHNICAL REPORT Improving Dissemination Strategies to Increase Technology Adoption by Smallholders in the Tunisian Arid Land Areas: An assessment from follow up survey Boubaker Dhehibi (1), Udo Rudiger (2), and Mohamed Zied Dhraief (3) (1) Resilient Agricultural Livelihood Systems (RALS) - International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) – Amman, Jordan. (2) Resilient Agricultural Livelihood Systems (RALS) - International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) – Tunis, Tunisia. (3) Department of Agricultural Economics (DAE) - National Institute for Agronomic Research of Tunisia (INRAT), Ariana – Tunisia. MAY 2019 Table of contents List of Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Objectives........................................................................................................................................ 4 3. Study Areas ..................................................................................................................................... 4 The Tunisian satellite site includes Zaghouan and Kairouan governorates....................................... 4 3.1. Zaghouan Governorate .......................................................................................................... 4 3.2. Kairouan governorate