Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

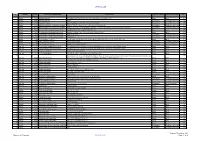

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Draft Outline

Tunisia Resilience and Community Empowerment Activity Quarterly Report Year Two, Quarter One – October 1, 2019 – December 30, 2019 Submission Date: January 30, 2019 Agreement Number: 72066418CA00001 Activity Start Date and End Date: SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 to AUGUST 31, 2023 AOR Name: Hind Houas Submitted by: Nadia Alami, Chief of Party FHI360 Tanit Business Center, Ave de la Fleurs de Lys, Lac 2 1053 Tunis, Tunisia Tel: (+216) 58 52 56 20 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. July 2008 1 Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... ii 1. Project Overview/ Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Project Description ........................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Analysis of Overall Program Progress Toward Results .................................................................... 4 2. Summary of Activities Conducted ............................................................................................................ 12 2.1 Objective 1: Strengthened Community Resilience ........................................................................... 12 RESULT 1.1: COMMUNITY MEMBERS, IN PARTICULAR MARGINALIZED GROUPS, DEMONSTRATE AN ENHANCED LEVEL OF ENGAGEMENT, -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

In Tunisia Policies and Legislations Related to the Democratic Transition

Policies and legislations The constitutional and legal framework repre- sents one of the most important signs of the related to the democratic transition in Tunisia. Especially by establishing rules, procedures and institutions in order to achieve the transition and its goals. Thus, the report focused on further operatio- nalization of the aforementioned framework democratic while seeking to monitor the events related to, its development and its impact on the transi- tion’s path. Besides, monitoring the difficulties of the second transition, which is related to the transition and political conflict over the formation of the go- vernment and what’s behind the scenes of the human rights official institutions. in Tunisia The observatorypolicies and rightshuman and legislation to democratic transition related . 27 Activating the constitutional and legal to submit their proposals until the end of January. Then, outside the major parties to be in the forefront of the poli- the committee will start its action from the beginning of tical scene. framework for the democratic transition February until the end of April 2020, when it submits its outcome to the assembly’s bureau. The constitution of 2015 is considered as the de facto framework for the democratic transition. And all its developments in the It is reportedly that the balances within the council have midst of the political life, whether in texts or institutions, are an not changed numerically, as it doesn’t witness many cases The structural and financial difficulties important indicator of the process of transition itself. of changing the party and coalition loyalties “Tourism” ex- The three authorities and the balance cept the resignation of the deputy Sahbi Samara from the of the Assembly Future bloc and the joining of deputy Ahmed Bin Ayyad to among them the Dignity Coalition bloc in the Parliament. -

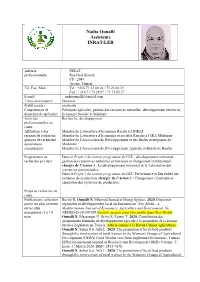

Nadia Ounalli Assistante INRAT/LER

Nadia Ounalli Assistante INRAT/LER Adresse INRAT, professionnelle Rue Hedi Karray CP : 2049 Ariana, Tunisia Tel, Fax, Mob. Tel : +216 71 23 00 24 / 71 23 02 39 Fax : +216 71 75 28 97 / 71 71 65 37 E-mail [email protected] Titres universitaire Doctorat Statut (grade) assistante Compétences et Politiques agricoles, gestion des ressources naturelles, développement territorial, domaines de spécialité Economie Sociale et Solidaire Activités Recherche, développement professionnelles en cours Affiliation à des Membre du Laboratoire d’Economie Rurale à l’INRAT réseaux de recherche, Membre du Laboratoire d’Economie et sociétés Rurales à l’IRA Médenine groupes de recherche, Membre de l’Association de Développement et des études stratégiques de associations Médenine scientifiques Membre de l’Association de Développement Agricole et Rurale de Haidra Programmes de Dans le Projet 3 du contrat programme du LER : développement territorial, recherche en cours gestion des ressources naturelles et foncières et changement institutionnel, chargée de l’Action 3 : Le développement territorial et la valorisation des ressources patrimoniales. Dans le Projet 2 du contrat programme du LER: Performance et Durabilité des systèmes de production, chargée de l’Action 3 : Changement climatique et adaptation des systèmes de production. Projet de recherche en cours Publications (sélection Bechir R, Ounalli N. Mhemed Jaoued et Mongi Sghaier, 2020. Disparités parmi les plus récentes régionales et développement local au Sud tunisien. New Medit - A ou les plus Mediterranean Journal of Economics, Agriculture and Environment. No. marquantes) 5 à 10 NEMED-D-20-00010R1(article accepté pour être publié dans New Medit) max Ounalli N, Marzougui N, Selmi S, Fazeni T, 2020. -

Arrêté2017 0057.Pdf

MINISTERE DE L’INDUSTRIE Les directions régionales du commerce sont chargées ET DU COMMERCE des opérations de vérification soit dans leurs bureaux permanents, soit dans les bureaux temporaires établis en dehors des chefs lieux des gouvernorats dans les localités Arrêté du ministre de l’industrie et du indiquées au tableau « A » annexé au présent arrêté, et commerce du 6 janvier 2017, relatif aux ce, conformément aux dates arrêtées en coordination opérations de vérification et de poinçonnage avec les autorités locales et régionales. des instruments de mesure au cours de Les opérations de vérification effectuées dans les l’année 2017. établissements où sont détenus les instruments de mesure se dérouleront aux dates convenues entre l’agence Le ministre de l’industrie et du commerce, nationale de métrologie et les établissements concernés, Vu la constitution, à l’exception des distributeurs de carburant fixes dont Vu le décret du 29 juillet 1909, relatif à la les dates de vérification sont indiquées dans le tableau « B » annexé au présent arrêté. vérification et la construction des poids et mesures, Art. 3 - Les détenteurs d’instruments de remplissage, instruments de pesage et de mesurage, tel que modifié de distribution ou de pesage à fonctionnement par le décret du 10 mars 1920 et le décret du 23 automatique doivent surveiller l’exactitude et le bon octobre 1952, notamment son article 13, fonctionnement de leurs instruments, et ce, en effectuant Vu la loi n° 99-40 du 10 mai 1999, relative à la périodiquement un contrôle statistique pondéral ou métrologie légale, telle que modifiée et complétée par volumétrique sur les produits mesurés. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Madera y bosques ISSN: 1405-0471 ISSN: 2448-7597 Instituto de Ecología A.C. Elaieb, Mohamed Tahar; Shel, Foued; Jalleli, Mounir; Langbour, Patrick; Candelier, Kévin Physical properties of four ring-porous hardwood species: influence of wood rays on tangential and radial wood shrinkage Madera y bosques, vol. 25, no. 2, e2521695, 2019 Instituto de Ecología A.C. DOI: 10.21829/myb.2019.2521641 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=61762610018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative doi: 10.21829/myb.2019.2521695 Madera y Bosques vol. 25, núm. 2, e12521695 Summer 2019 Scientific papers Physical properties of four ring-porous hardwood species: influence of wood rays on tangential and radial wood shrinkage Propiedades físicas de la madera de cuatro especies de latifoliadas de porosidad anular: influencia de los radios sobre las contracciones tangencial y radial Mohamed Tahar Elaieb1, Foued Shel2, Mounir Jalleli3, Patrick Langbour4,5, and Kévin Candelier4,5* 1 University of Carthage. National Research Institute of 2 Regional Center for Research in Horticulture and 4 Center for International Cooperation in Agricultural Rural Engineering, Water and Forests. Laboratory of Organic Agriculture. Sousse Governorate, Tunisia. Research for Development. UPR BioWooEB. Management and Valorization of Forest Resources. Sousse, Tunisia. Montpellier, France. Ariana, Tunisia. 3 General Directorate of Financing. Tunis Belvédère, 5 University of Montpellier. Montpellier, France. Tunisia. * Corresponding author. [email protected] ABSTRACT Some relationships between ray proportions, strength and shrinkage properties and basic density in hardwood species were highlighted. -

Fiche Du Plan De Passation Des Marchés

Fiche du Plan de Passation des Marchés I. Généralités 1. Information sur le Projet Nom du Projet: Projet d'Investissement des le Secteur de l'Eau (PISEAU II) Pays: Republique Tunisienne Référence du Projet : PISEAU II Public Disclosure Authorized Numéro du Prêt/Crédit: BIRD-BAD-AFD N°: 7726-TN Projet ID P095847 Agencies 23 CRDAs: Ariana; Beja; Ben Arous; Bizerte; Gabes; Gafsa; Jendouba; Kairouan; Kasserine; Kebili; Kef; Mahdia; Manouba; Medenine; Monastir; Nabeul; Sfax, Sidi Bouzid; Siliana; Sousse; Tataouine; Tozeur; Zaghouan 2. Date d'approbation du Plan de Passation des Marchés Approbation 1 : juin-09 Révision 2 : 2-déc.-10 Révision 3 : 20-janv.-11 Révision 4 : 8-juin-11 Révision 5 : 5-janv.-12 Public Disclosure Authorized Révision 6 : 28-oct.-13 3. Date d'Avis Général de Passation des Marchés 30-Jun-08 II. Seuils pour les Fournitures, Travaux et Services autres que Services de Consultants 1. Seuil de Revue à Priori Seuil de Revue à Priori 1a. Type de Marché (USD) Commentaires Fournitures ≥ 500,000 Travaux ≥ 5,000,000 Travaux STEG (par Entente Directe) ≥ 150,000 Seuil de la méthode de 1b. Méthode de Passation des Marchés PM (USD) Commentaires Public Disclosure Authorized AOI Travaux >10,000,000 - AON Travaux >200,000 et ≤10,000,000 Consultations d'Entrepreneurs (Travaux) (CEN) ≤200,000 AOI Fournitures >1,000,000 AON Fournitures >100,000 et ≤1,000,000 Consultations de Fournisseurs (Fournitures) (CF) ≤ 100,000 2. Prequalification : A/NA 3. Procédure proposée pour les Composantes des Marchés Communautaires : A/NA Public Disclosure Authorized 4. Référence du Manuel de Procédures ou du Manuel de Passation des Marchés : MP applicable en date du : 16 avril 2009 5. -

The Panoramictour of Tunus

The PanoramicTour of Tunus 26 November 2016 08:00 Departure from the conference center Professional and experienced licensed guide during the tours. Transportation by a comfortable AC non smoking Luxurious car / Van with professional driver. 18:30 Returning to the hotel Price: FREE During the Tour will visit the Historical Places Sousse Old Town Sousse Archelogical Museum Great Mosque of Sousse Port El Kantaoui Note: Only, the museums entrance fee and lunch will be paid by the participants. Historical Places Information 1. Sausse Old Town Sousse or Soussa is a city in Tunisia, capital of the Sousse Governorate. Located 140 kilometres (87 miles) south of the capital Tunis, the city has 271,428 inhabitants (2014). Sousse is in the central-east of the country, on the Gulf of Hammamet, which is a part of the Mediterranean Sea. The name may be of Berber origin: similar names are found in Libya and in the south of Morocco (Bilād al-Sūs). Its economy is based on transport equipment, processed food, olive oil, textiles and tourism. The city allied itself with Rome during the Punic Wars, thereby escaping damage or ruin and entered a relatively peaceful 700-year period under the Pax Romana. Livy wrote that Hadrumetum was the landing place of the Roman army under Scipio Africanus in the second Punic War. Roman usurper Clodius Albinus was born in Hadrumetum. 2. Sousse Archelogical Museum The museum is housed in the Kasbah of the City's Medina which was founded in the 11th century AD. The museum was established in 1951. It reopened its doors to the public in 2012 after the collections were rearranged and the building restored. -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

Tunisia Fragil Democracy

German Council on Foreign Relations No. 2 January 2020 – first published in REPORT December 2018 Edited Volume Tunisia’s Fragile Democracy Decentralization, Institution-Building and the Development of Marginalized Regions – Policy Briefs from the Region and Europe Edited by Dina Fakoussa and Laura Lale Kabis-Kechrid 2 No. 2 | January 2020 – first published in December 2018 Tunisia’s Fragile Democracy REPORT The following papers were written by participants of the workshop “Promotion of Think Tank Work on the Development of Marginalized Regions and Institution-Building in Tunisia,” organized by the German Council on Foreign Relations’ Middle East and North Africa Program in the summer and fall of 2018 in cooperation with the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Tunis. The workshop is part of the program’s project on the promotion of think tank work in the Middle East and North Africa, which aims to strengthen the scientific and technical capacities of civil society actors in the region and the EU who are engaged in research and policy analysis and advice. It is realized with the support of the German Federal Foreign Office and the Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations (ifa e.V.). The content of the papers does not reflect the opinion of the DGAP. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors. The editorial closing date was October 28, 2018. Authors: Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi, Mohamed Lamine Bel Haj Amor, Arwa Ben Ahmed, Elhem Ben Aicha, Ahmed Ben Nejma, Laroussi Bettaieb, Zied Boussen, Giulia Cimini, Rim Dhaouadi, Jihene Ferchichi, Darius Görgen, Oumaima Jegham, Tahar Kechrid, Maha Kouas, Anne Martin, and Ragnar Weilandt Edited by Dina Fakoussa and Laura Lale Kabis-Kechrid No.