Thoughts from the Forest, Ecovillage and Sickbed on Our Beliefs About Nature and Anarcho-Primitivism by Ed Jones, November 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resistance: Do the Ends Justify the Means?

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282069814 Resistance: Do the Ends Justify the Means? Article · July 2014 DOI: 10.5822/978-1-61091-458-1_28 CITATIONS READS 2 40 1 author: Bron Raymond Taylor University of Florida 78 PUBLICATIONS 1,012 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Radical Environmentalism (interdisciplinary analysis of) View project Biological conservation and ethics: human rights, animal rights, earth rights View project All content following this page was uploaded by Bron Raymond Taylor on 02 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. State of the World 2013 IS SUSTAINABILITY Still Possible? THE WORLDWATCH INSTITUTE CHAPTER 28 Resistance: Do the Ends Justify the Means? Bron Taylor Has the time come for a massive wave of direct action resistance to acceler- ating rates of environmental degradation around the world—degradation that is only getting worse due to climate change? Is a new wave of direct action resistance emerging, one similar but more widespread than that sparked by Earth First!, the first avowedly “radical” environmental group? The radical environmental movement, which was formed in the United States in 1980, controversially transformed environmental politics by en- gaging in and promoting civil disobedience and sabotage as environmen- talist tactics. By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, when the most militant radical environmentalists adopted the Earth Liberation Front name, arson was increasingly deployed. The targets included gas-guzzling sport utility vehicles, U.S. Forest Service and timber company offices, resorts and com- mercial developments expanding into wildlife habitat, and universities and corporations engaged in research creating genetically modified organisms. -

Culture of Resistance – Interview with Lierre Keith, Co-Author of Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet (With

Culture of Resistance – Interview with Lierre Keith, co-author of Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet (with Derrick Jensen and Aric McBay – Seven Stories Press, 2011) Helen Moore: Many people reading this will have woken up to the fact that industrial civilisation is having catastrophic effects on our planet, and they may also be engaged in artistic or scientific endeavours to address the ecological and spiritual crisis we collectively face. Human consciousness is clearly at a crossroads right now, and there’s growing awareness of our deep interconnection with all beings and a need for radical change in how we live. However, you and your co-authors have concluded that for life on Earth to be preserved, we require a co-ordinated resistance movement. Could you begin by talking about this? Lierre Keith: Your question cuts to the heart of the difference between liberalism and radicalism. For liberals, social reality is constituted of thoughts and ideas. This is called idealism. Social change, then, happens through education, through rational discussion and discourse. It happens by changing people’s minds. In contrast, radicals understand that society is made up of material institutions that organize the subordination of one group to another. Education is always a necessary activity for a resistance movement, but education for what purpose? If education is the end goal, that’s a liberal approach. For radicals, education raises consciousness and gives people the tools to name their experience and hopefully they are then inspired to join a resistance movement. That’s the goal of political education. It’s that resistance that confronts and dismantles the structures of power. -

WHY WE ARE FEMINISTS by Lierre Keith GET INVOLVED

DEEP GREEN RESISTANCE (DGR) IS A MOVEMENT BASED PARTLY ON THE BOOK, BY DERRICK JENSEN, LIERRE KEITH, AND ARIC MCBAY CALLED DEEP GREEN RESISTANCE: STRATEGY TO SAVE THE PLANET. DGR HAS A PLAN OF ACTION FOR ANYONE DETERMINED TO WHY WE ARE FIGHT FOR THIS PLanet—and WIN. SUBSCRIBE TO THE WEBSITE, GIVE FEEDBACK, AND LET OTHERS KNOW. TAKE ACTION. START OR JOIN A DGR FEMINISTS ACTION GROUP. VOLUNTEER. BY GET INVOLVED Website: deepgreenresistancenewyork.wordpress.com LIERRE KEITH Facebook.com/dgrnewyork Phone: (917) 830-3595 E-mail: [email protected] deepgreenresistance.org WHY WE ARE FEMINISTS: • Langford, Rae and June D. Thompson. Mosby’s Handbook of Dis- eases, 3rd Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2005. THE FEMINIST FRAMEWORK OF DGR • Lenskyj, Helen. “An Analysis of Violence Against Women: A Manu- BY LIERRE KEITH al for Educators and Administrators.” Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1992. • Jeffreys, Sheila. “Sado-Masochism: The Erotic Cult of Fascism.” Q: Is DGR a feminist organization? Lesbian Ethics 2, No. 1, Spring 1986. A: Unconditionally yes. • Smedley, Audrey. Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2007. In the words of Andrea Dworkin, “Feminism is the political • “UN calls for strong action to eliminate violence against wom- en.” UN News Centre. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story. practice of fighting male supremacy in behalf of women as asp?NewsID=16674&Cr=&Cr1=. a class.”1 SUGGESTED READING • Andrea Dworkin. Life and Death. New York: The Free Press, 1997. Let’s start with the phrase “women as a class.” From a radical • Cordelia Fine. -

![HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6562/hums-4904a-schedule-mondays-11-35-2-25-each-session-is-in-two-halves-a-and-b-86562.webp)

HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]

CARLETON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES Humanities 4904 A (Winter 2011) Mahatma Gandhi Across Cultures Mondays 11:35-2:25 Prof. Noel Salmond Paterson Hall 2A46 Paterson Hall 2A38 520-2600 ext. 8162 [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays 2:00 - 4:00 (Or by appointment) This seminar is a critical examination of the life and thought of one of the pivotal and iconic figures of the twentieth century, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – better known as the Mahatma, the great soul. Gandhi is a bridge figure across cultures in that his thought and action were inspired by both Indian and Western traditions. And, of course, in that his influence has spread across the globe. He was shaped by his upbringing in Gujarat India and the influences of Hindu and Jain piety. He identified as a Sanatani Hindu. Yet he was also influenced by Western thought: the New Testament, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, Count Leo Tolstoy. We will read these authors: Thoreau, On Civil Disobedience; Ruskin, Unto This Last; Tolstoy, A Letter to a Hindu and The Kingdom of God is Within You. We will read Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, and a variety of texts from his Collected Works covering the social, political, and religious dimensions of his struggle for a free India and an India of social justice. We will read selections from his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the book that was his daily inspiration and that also, ironically, was the inspiration of his assassin. We will encounter Gandhi’s clash over communal politics and caste with another architect of modern India – Bimrao Ambedkar, author of the constitution, Buddhist convert, and leader of the “untouchable” community. -

(Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Including Index of Epistles

Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies including index of epistles Compiled for Yearly Meeting 2020 Q Logo - Sky - CMYK - Black Text.pdf 1 26.04.2016 04.55 pm C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Credit: Mike Pinches for BYM Pinches for Mike Credit: This booklet is part of ‘Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain 2019’, a set of publications published for Yearly Meeting. The full set comprises: 1. The Yearly Meeting programme, with introductory material for Yearly Meeting 2019 and annual reports of Meeting for Sufferings, Quaker Stewardship Committee and other related bodies 2. Testimonies 3. Minutes, to be distributed after the conclusion of Yearly Meeting 4. The formal Trustees’ annual report including financial statements for the year ended December 2019 5. Tabular statement. All documents are available online at www.quaker.org.uk/ym. If these do not meet your accessibility needs, or the needs of someone you know, please email [email protected]. Printed copies of all documents will be available at Yearly Meeting. All Quaker faith & practice references are to the online edition, which can be found at www.quaker.org.uk/qfp. Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Testimonies Contents Epistles 5 Introduction 6 Warren Adams 8 Judith Mary Effer 9 Marion Fairweather 11 Sheila J. Gatiss 12 Joyce Gee 14 Joan Gibson 16 David Henshaw 17 Kate Joyce 20 Richard Lacock 23 Lesley Parker 25 Erika Margarethe Zintl Pearce 27 Angela Maureen Pivac 30 Margaret Rowan 32 Peter Rutter 34 Margaret Slee 36 Rachel Smith 38 Claire Watkins 39 Allan N. -

From Engineering Hydrology to Earth System Science: Milestones in the Transformation of Hydrologic Science

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 1665–1693, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-1665-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. From engineering hydrology to Earth system science: milestones in the transformation of hydrologic science Murugesu Sivapalan1,* 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Department of Geography and Geographic Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA * Invited contribution by Murugesu Sivapalan, recipient of the EGU Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership 2017. Correspondence: Murugesu Sivapalan ([email protected]) Received: 13 November 2017 – Discussion started: 15 November 2017 Revised: 2 February 2018 – Accepted: 5 February 2018 – Published: 7 March 2018 Abstract. Hydrology has undergone almost transformative hydrology to Earth system science, drawn from the work of changes over the past 50 years. Huge strides have been made several students and colleagues of mine, and discuss their im- in the transition from early empirical approaches to rigorous plication for hydrologic observations, theory development, approaches based on the fluid mechanics of water movement and predictions. on and below the land surface. However, progress has been hampered by problems posed by the presence of heterogene- ity, including subsurface heterogeneity present at all scales. எப்ெபாள் யார்யாரவாய் ் க் ேகட்ம் The inability to measure or map the heterogeneity every- அப்ெபாள் ெமய் ப்ெபாள் காண் ப த where prevented the development of balance equations and In whatever matter and from whomever heard, associated closure relations at the scales of interest, and has Wisdom will witness its true meaning. -

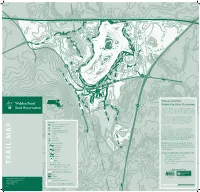

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

A New Look at Thoreau

ADDENDUM A NEW LOOK AT THOREAU In the summer of Thoreau did not put me to sleep. He shook me awake, 1984, as a college student hungry pointing me toward an alternative vision of the good life. to see the halls of power up close, I took a summer internship on Natural History, I saw just the thing to usher me blissfully into unconsciousness Capitol Hill. that night. Out of the corner of my eye, I’d spotted the bright green cover of It was heady Walden in the window of the museum bookshop. stuff for a 20-year-old. I shared a row Two years earlier, I’d been assigned to read Henry David Thoreau in American house with three other students a few Lit class and found him a colossal bore. His questioning of material gain left me blocks from the Capitol, passing the cold. I dreamed of a life after college that included more, not fewer, possessions. Library of Congress and Supreme I also wanted to be at the center of things, not sequestered in a shack by a pond. Court on my walk to work. Someone Walden seemed like a manual in how not to succeed. got me an insider tour of the White Finally, an author I’d endured in the classroom would have some use for me, his House, which allowed me to stick my prose as potent as a tranquilizer. I bought Walden from the Smithsonian and took head into the Oval Office and gaze it home, convinced that I carried literary laudanum in my hands. -

What Is Anarcho-Primitivism?

The Anarchist Library Anti-Copyright What is Anarcho-Primitivism? Anonymous Anonymous What is Anarcho-Primitivism? 2005 Retrieved on 11 December 2010 from blackandgreenbulletin.blogspot.com theanarchistlibrary.org 2005 Rousseau, Jean Jacques. (2001). On the Inequality among Mankind. Vol. XXXIV, Part 3. The Harvard Classics. (Origi- nal 1754). Retrieved November 13, 2005, from Bartleby.com: www.bartleby.com Sahlins, Marshall. (1972). “The Original Affluent Society.” 1–39. In Stone Age Economics. Hawthorne, New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Sale, Kirkpatrick. (1995a). Rebels against the future: the Luddites and their war on the Industrial Revolution: lessons for the computer age. New York: Addison-Wesley. — . (1995b, September 25). “Unabomber’s Secret Treatise: Is There Method In His Madness?” The Nation, 261, 9, 305–311. “Situationism”. (2002). The Art Industri Group. Retrieved Novem- ber 15, 2005, from Art Movements Directory: www.artmovements.co.uk Stobbe, Mike (2005, Dec 8). “U.S. Life Expectancy Hits All- Time High.” Retrieved December 8, 2005, from Yahoo! News: news.yahoo.com — Tucker, Kevin. (2003, Spring). “The Spectacle of the Symbolic.” Species Traitor: An Insurrectionary Anarcho-Primitivist Journal, 3, 15–21. U.S. Forestland by Age Class. Retrieved December 7, 2005, from Endgame Research Services: www.endgame.org Zerzan, John. (1994). Future Primitive and Other Essays. Brooklyn: Autonomedia. — . (2002, Spring). “It’s All Coming Down!” In Green Anarchy, 8, 3–3. — . (2002). Running on Emptiness: The Pathology of Civilisation. Los Angeles: Feral House. Zinn, Howard. (1997). “Anarchism.” 644–655. In The Zinn Reader: Writings on disobedience and democracy. New York: Seven Sto- ries. 23 Kassiola, Joel Jay. (1990) The Death of Industrial Civilization: The Limits to Economic Growth and the Repoliticization of Advanced Industrial Society. -

Agrarianism: an Ideology of the National FFA Organization

Journal of Agricultural Education Volume 54, Number 3, pp. 28 – 40 DOI: 10.5032/jae.2013.03028 Agrarianism: An Ideology of the National FFA Organization Michael J. Martin Colorado State University Tracy Kitchel University of Missouri The traditions of the National FFA Organization (FFA) are grounded in agrarianism. This ideology fo- cuses on the ability of farming and nature to develop citizens and integrity within people. Agrarianism has been an important thread of American rhetoric since the founding of country. The ideology has mor- phed over the last two centuries as the country developed from a nation of farmers to an industrial world power. The agrarian ideology that resonated in rural America during the formation of the FFA was southern agrarianism. Southern agrarian ideology argued for self-reliance and adherence to past tradi- tions. These concepts appear in the FFA traditions of the creed, opening ceremony, motto, and awards. The historical growth and success of the FFA within rural communities demonstrates the ability of the southern agrarian ideology to connect with contemporary rural values. However, the southern agrarian ideology may not connect with the culture of diverse, urban, or suburban students. Advisers of diverse, urban, or suburban FFA chapters may need to reconceptualize the FFA traditions to accommodate their students. Keywords: National FFA Organization; philosophy; ideology; agrarianism The theme Beyond Diversity to Cultural LaVergne, Larke, Elbert, & Jones, 2011). One Proficiency resonated at the 2011 American As- study highlighted how some non-FFA members sociation for Agricultural Education (AAAE) viewed FFA members as hicks (Phelps, Henry, conference. Fittingly, AAAE invited James & Bird, 2012). -

Anarchy Works Anarchy Works by Peter Gelderloos

Anarchy Works Anarchy Works by Peter Gelderloos Ardent Press, 2010 No copyright This book is set in Gentium. No more talk about the old days, it’s time for something great. I want you to get out and make it work… Thom Yorke Dedicated to the wonderful people of RuinAmalia, La Revoltosa, and the Kyiv infoshop, for making anarchy work. Although this book started out as an individual project, in the end a great many people, most of whom prefer to remain anonymous, helped make it possible through proofreading, fact-checking, recommending sources, editing, and more. To acknowledge only a small part of this help, the author would like to thank John, Jose, Vila Kula, aaaa!, L, J, and G for providing computer access throughout a year of moves, evictions, crashes, viruses, and so forth. Thanks to Jessie Dodson and Katie Clark for helping with the research on another project, that I ended up using for this book. Also thanks to C and E, for lending their passwords for free access to the databases of scholarly articles available to university students but not to the rest of us. There are hidden stories all around us, growing in abandoned villages in the mountains or vacant lots in the city, petrifying beneath our feet in the remains of societies like nothing we’ve known, whispering to us that things could be different. But the politician you know is lying to you, the manager who hires and fires you, the landlord who evicts you, the president of the bank that owns your house, the professor who grades your papers, the cop who rolls your street, the reporter -

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth © 2012 PM Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978–1–60486–484–7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927981 Cover: John Yates / www.stealworks.com Interior design by briandesign 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com contents Introduction 1 Robert H. Haworth Section I Anarchism & Education: Learning from Historical Experimentations Dialogue 1 (On a desert island, between friends) 12 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 1 Anarchism, the State, and the Role of Education 14 Justin Mueller chapteR 2 Updating the Anarchist Forecast for Social Justice in Our Compulsory Schools 32 David Gabbard ChapteR 3 Educate, Organize, Emancipate: The Work People’s College and The Industrial Workers of the World 47 Saku Pinta cHAPteR 4 From Deschooling to Unschooling: Rethinking Anarchopedagogy after Ivan Illich 69 Joseph Todd Section II Anarchist Pedagogies in the “Here and Now” Dialogue 2 (In a crowded place, between strangers) 88 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 5 Street Medicine, Anarchism, and Ciencia Popular 90 Matthew Weinstein cHAPteR 6 Anarchist Pedagogy in Action: Paideia, Escuela Libre 107 Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan cHAPteR 7 Spaces of Learning: The Anarchist Free Skool 124 Jeffery Shantz cHAPteR 8 The Nottingham Free School: Notes Toward a Systemization of Praxis 145 Sara C.