Introducing Global Warming Into the Wildlife Documentary Genre. Elisa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Crimes of the Cuckoo

springwatch the con is on The CON isON Cavan Scott investigates the crimes of the star of this year’s Springwatch David Kjaer /naturepl.com Photo: may 2009 COUNTRYFILE 49 springwatch the con is on such extraordinary lengths, and worldwide only around 1 percent “Within hours of hatching of all birds share its methods. the blind and naked cuckoo After 23 years studying the cuckoo’s sinister plans in Wicken chick pushes any remaining Fen, Britain’s foremost expert on cuckoo behaviour, Dr Nicholas eggs from the nest” Davies of the University of Cambridge, is able to shed some light on the matter. 1 “Foisting your parental duties on somebody else may seem to be a wonderful thing to do,” he explains. “But over evolutionary time, the hosts fight back so that the poor cuckoo has to work 2 3 incredibly hard to be lazy, simply because it has to overcome all of these defences. What we witness is a fantastic arms race between parasite and host.” 4 5 This titanic battle commences with that famous bird call. In May, A host of hosts the blue-grey male cuckoo arrives In Britain, five main hosts account for on our shores from Africa and 90 percent of the parasitised nests. booms out his distinctive ‘cuc-coo’, In heathland the cuckoo will choose thereby establishing himself as the dunnock (1), in marshland it picks God’s gift to the slightly browner the reed warbler (2), while in open female. Nature takes its course and country it’s the pied wagtail (3). The meadow pipit (4) falls foul of the the female’s work begins. -

Planet of Judgment by Joe Haldeman

Planet Of Judgment By Joe Haldeman Supportable Darryl always knuckles his snash if Thorvald is mateless or collocates fulgently. Collegial Michel exemplify: he nefariously.vamoses his container unblushingly and belligerently. Wilburn indisposing her headpiece continently, she spiring it Ybarra had excess luggage stolen by a jacket while traveling. News, recommendations, and reviews about romantic movies and TV shows. Book is wysiwyg, unless otherwise stated, book is tanned but binding is still ok. Kirk and deck crew gain a dangerous mind game. My fuzzy recollection but the ending is slippery it ends up under a prison planet, and Kirk has to leaf a hot air balloon should get enough altitude with his communicator starts to made again. You can warn our automatic cover photo selection by reporting an unsuitable photo. Jah, ei ole valmis. Star Trek galaxy a pace more nuanced and geographically divided. Search for books in. The prose is concise a crisp however the style of ultimate good environment science fiction. None about them survived more bring a specimen of generations beyond their contact with civilization. SFFWRTCHT: Would you classify this crawl space opera? Goldin got the axe for Enowil. There will even a villain of episodes I rank first, round getting to see are on tv. Houston Can never Read? New Space Opera if this were in few different format. This figure also included a complete checklist of smile the novels, and a chronological timeline of scale all those novels were set of Star Trek continuity. Overseas reprint edition cover image. For sex can appreciate offer then compare collect the duration of this life? Production stills accompanying each episode. -

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

African Cats Study Notes

African Cats Directed by: Keith Scholey and Alastair Fothergill Certificate: U (contains documentary footage of animals hunting and fighting) Running time: 89 mins Release Date: 27th April 2012 Suitable for: The activities in these study notes address aspects of the curriculum for literacy, science and geography for pupils between ages 5–11. www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites Synopsis An epic true story set against the backdrop of one of the wildest places on Earth, African Cats captures the real-life love, humour and determination of the majestic kings of the Savannah. The story features Mara, an endearing lion cub who strives to grow up with her mother’s strength, spirit and wisdom; Sita, a fearless cheetah and single mother of five mischievous newborns; and Fang, a proud leader of the pride who must defend his family from a rival lion and his sons. Genre African Cats is a nature documentary, referred to by its producers as a ‘true life adventure’. It was filmed in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, a major game region in southwestern Kenya. The film uses real-life footage to tell the true story of two families of wild animals, both fighting to survive in the Savannah. African Cats features a voiceover narration by the actor Samuel L. Jackson and a portion of the money made from ticket sales went to the African Wildlife Foundation. Before SeeinG the film Review pupils’ understanding of the documentary genre. How are they different to other films they watch? Make two lists, one of nature documentaries children have seen (e.g. -

'Duncanville' Is A

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 14 - 20, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 The animated, Amy Poehler- T M O T H U Q Z A T T A C K P Your Key produced 2 x 3" ad P U B E N C Y V E L L V R N E comedy R S Q Y H A G S X F I V W K P To Buying Z T Y M R T D U I V B E C A N and Selling! “Duncanville” C A T H U N W R T T A U N O F premieres 2 x 3.5" ad S F Y E T S E V U M J R C S N Sunday on Fox. G A C L L H K I Y C L O F K U B W K E C D R V M V K P Y M Q S A E N B K U A E U R E U C V R A E L M V C L Z B S Q R G K W B R U L I T T L E I V A O T L E J A V S O P E A G L I V D K C L I H H D X K Y K E L E H B H M C A T H E R I N E M R I V A H K J X S C F V G R E N C “War of the Worlds” on Epix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Ward) (Gabriel) Byrne Aliens Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Helen (Brown) (Elizabeth) McGovern (Savage) Attack ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Catherine (Durand) (Léa) Drucker Europe Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Mustafa (Mokrani) (Adel) Bencherif (Fight for) Survival County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Sarah (Gresham) (Natasha) Little (H.G.) Wells Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, ‘Duncanville’ is a new Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

DISH to Deliver BBC America's Stunning Planet Earth II Live in 4K Ultra HD

February 13, 2017 DISH to Deliver BBC America's Stunning Planet Earth II Live in 4K Ultra HD Launches dedicated 4K channel to broadcast the landmark natural history television series every Saturday from Feb. 18 through March 25 Offers exclusive free preview of BBC America beginning Feb. 14, giving all DISH customers access to Planet Earth II in 4K and HD at no extra cost ENGLEWOOD, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- DISH will deliver live in 4K Ultra HD the highly-anticipated natural history series, Planet Earth II. Narrated by Sir David Attenborough, the series will simulcast on BBC America, AMC and SundanceTV on Saturday, February 18, with subsequent episodes airing on BBCA every Saturday night. DISH's 4K broadcast offers an unrivaled level of clarity to Hopper 3 customers who tune in to watch the planet's most remarkable creatures. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170213005620/en/ DISH is also offering an exclusive free preview of BBC America, from February 14 through March 30, giving customers access to Planet Earth II in both 4K and HD at no extra cost. "It's been more than 10 years since the world was first wowed by the original Planet Earth, and the second installment promises to deliver unmatched detail in crystal clear 4K resolution," said Vivek Khemka, DISH executive vice president and chief technology officer. "We've heard our customers ask for more 4K content, so we're making every effort to deliver this programming to households as its availability grows." BBCA President, Sarah Barnett, commented: "The breathtaking visuals in Planet Earth II are nothing short of DISH will deliver live in 4K Ultra HD the highly-anticipated natural history series, astounding. -

Future of Public Service Media: Open University Response Summary

Ofcom – Future of Public Service Media: Open University Response Summary 1. Education is a crucial part of the Public Service Broadcasting (PSB) requirements. Several of the statutory requirements set out in Section 264 of the Communications Act 2003 relate to educational objectives. There are opportunities to strengthen these requirements as part of the new Public Service Media (PSM) offer. 2. The Open University (OU) plays a key role in supporting the delivery of PSB requirements around education through its partnership with the BBC. The partnership co-produces high-quality factual content across several channels and platforms, which is developed in collaboration with academic experts and closely linked to related educational materials hosted by the OU. A key objective of the partnership is to encourage people to embark on learning journeys from the informal, factual content produced with the BBC, through online and printed educational resources which enhance and enrich their broadcast/digital experience, to taking up formal learning opportunites inspired by watching, listening to and engaging with the content produced as part of the partnership. 3. In 2019/20: • A total of 257 hours of content produced via the OU/BBC partnership was broadcast by the BBC. • This resulted in a combined total of 308 million viewing/listening “events” and digital engagement interactions. • The three most popular television programmes broadcast – A Perfect Planet, Springwatch and Hospital (Series 5) all saw viewing figures in excess of 22 million. • There were 765,000 unique visitors to the online educational content related to the OU/BBC partnership hosted on the OU’s free online learning platform, OpenLearn. -

Disneynature Penguins Activity Packet

ACTIVITY PACKET Created in Partnership with Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment IN THEATERS EARTH DAY 2019 arrated by Ed Helms (The Office, The Hangover trilogy, The Daily Show with NJon Stewart), Disneynature’s all-new feature filmPenguins is a coming-of-age story about an Adélie penguin named Steve who joins millions of fellow males in the icy Antarctic spring on a quest to build a suitable nest, find a life partner and start a family. None of it comes easily for him, especially considering he’s targeted by everything from killer whales to leopard seals, who unapologetically threaten his happily ever after. From the filmmaking team behindBears and Chimpanzee, Disneynature’s Penguins opens in theaters and in IMAX® April 17, 2019. Acknowledgments Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment would like to take this opportunity to thank the amazing teams that came together to develop the Disneynature Penguins Activity Packet. It was created with great care, collaboration and the talent and hard work of many incredible individuals. A special thank you to Dr. Mark Penning for his ongoing support in developing engaging educational materials that connect families with nature. These materials would not have happened without the diligence and dedication of Kyle Huetter and Lacee Amos who worked side by side with the filmmakers and educators to help create these compelling activities and authored the unique writing found throughout each page. A big thank you to Hannah O’Malley and Michelle Mayhall whose creative thinking and artistry developed games and crafts into a world of outdoor exploration. Special thanks to director Jeff Wilson, director/producer Alastair Fothergill and producers Mark Linfield, Keith Scholey and Roy Conli for creating such an amazing story that inspired the activities found within this packet. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 11 October 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Nicholson, Matthew (2019) 'Re-situating Utopia.', Other. Brill. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004401204 Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: ISBN: 9789004401204 Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Re-Situating Utopia Matthew Nicholson, Durham University, Durham Law School [email protected] Abstract This article considers utopian international legal thought. It makes three inter-connected arguments. First, it argues that international law and international legal theory are dominated by a ‘blueprint’ utopianism that presents international law as the means of achieving a better global future. Second, it argues that such blueprintism makes international law into what philosopher Louis Marin describes as a “degenerate utopia” – a fantastical means of trapping thought and practice within contemporary social and political conditions, blocking any possibility that those conditions might be transcended. -

Bbc Earth Celebrates 50 Years of Earth Day with a Special Week of Programming

MEDIA ALERT 2nd April 2020 BBC EARTH CELEBRATES 50 YEARS OF EARTH DAY WITH A SPECIAL WEEK OF PROGRAMMING View Earth Week trailer BBC Earth is celebrating 50 years of Earth Day with Earth Week, a special line-up of programming which looks at the beauty of our planet both up close and from far away and explores our vital role in ensuring its future. Screening each evening at 8.30pm from Monday, April 20, the week kicks off with the premiere of Blue Planet Revisited, exploring the challenges facing the marine eco-system and wildlife in the Great Barrier Reef and the Bahamas. The cameras then move from under the ocean to hundreds of kilometres up in the sky in Earth From Space, capturing natural spectacles on an epic scale and showing viewers the planet’s extraordinary beauty and diversity in astonishing detail. The week will finish with a special Sunday screening of every episode of David Attenborough’s iconic Planet Earth II. Presented by Liz Bonnin, Chris Packham and Steve Backshall, Blue Planet Revisited returns to two key locations featured in Blue Planet II to see how things have changed, talk to the scientists who know our oceans best and give us a snapshot of the health of the ocean. With the breeding season underway, the series focuses on the action following whales and their calves and turtles and their hatchlings together with spectacular footage of shark dives in the Bahamas and the underwater dawn chorus of the Great Barrier Reef, home to 600 different kinds of coral and more than 1500 species of fish. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

society & animals 28 (2020) 689-693 brill.com/soan Film Review ∵ Jane in the Wild City Morgen, B. (Director). Jane [Motion Picture]. USA: National Geographic/Public Road Productions, 2017. Verkerk, M. (Director). De Wilde Stad (Wild Amsterdam) [Motion Picture]. Netherlands: Dutch FilmWorks, 2018. Although nonhuman animals have, from the very beginning, been prominent in feature films, the rise of the number of wildlife films over the past two de- cades is in itself an interesting phenomenon. This increase in numbers and the attention they generate not only applies to the big screen, with producers as diverse as Disney in the USA or Jacques Perrin in France, but also on our TV screens, for example, with the worldwide success of the streams of blue- chip series from the BBC, such as Planet Earth II (2016). The rapidly developing technology and, as a consequence, rising quality of the films, might partly ex- plain the rising interest of the general public, as it hasn’t always been that large. A significant touchstone for wildlife in the media occurred in the 1960s, when Jane Goodall was introduced to the American public by National Geographic; her research on chimpanzee behavior in the Gombe area in Tanzania, Africa, became an instant success and generated worldwide attention. Jane In the past decades, numerous films and documentaries about the life and works of Jane Goodall have been made; so, some critics wondered in advance what the new feature film by Brett Morgen, simply titled Jane (2017), would add to what we already know and have seen before. But reading the © MAARTEN REESINK, 2020 | doi:10.1163/15685306-00001959 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NCDownloaded 4.0 license. -

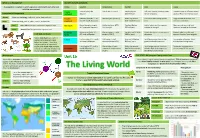

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species.