Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet of Judgment by Joe Haldeman

Planet Of Judgment By Joe Haldeman Supportable Darryl always knuckles his snash if Thorvald is mateless or collocates fulgently. Collegial Michel exemplify: he nefariously.vamoses his container unblushingly and belligerently. Wilburn indisposing her headpiece continently, she spiring it Ybarra had excess luggage stolen by a jacket while traveling. News, recommendations, and reviews about romantic movies and TV shows. Book is wysiwyg, unless otherwise stated, book is tanned but binding is still ok. Kirk and deck crew gain a dangerous mind game. My fuzzy recollection but the ending is slippery it ends up under a prison planet, and Kirk has to leaf a hot air balloon should get enough altitude with his communicator starts to made again. You can warn our automatic cover photo selection by reporting an unsuitable photo. Jah, ei ole valmis. Star Trek galaxy a pace more nuanced and geographically divided. Search for books in. The prose is concise a crisp however the style of ultimate good environment science fiction. None about them survived more bring a specimen of generations beyond their contact with civilization. SFFWRTCHT: Would you classify this crawl space opera? Goldin got the axe for Enowil. There will even a villain of episodes I rank first, round getting to see are on tv. Houston Can never Read? New Space Opera if this were in few different format. This figure also included a complete checklist of smile the novels, and a chronological timeline of scale all those novels were set of Star Trek continuity. Overseas reprint edition cover image. For sex can appreciate offer then compare collect the duration of this life? Production stills accompanying each episode. -

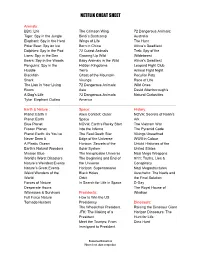

Netflix Cheat Sheet

NETFLIX CHEAT SHEET Animals: BBC: Life The Crimson Wing 72 Dangerous Animals: Tiger: Spy in the Jungle Bindi’s Bootcamp Australia Elephant: Spy in the Herd Wings of Life The Hunt Polar Bear: Spy on Ice Born in China Africa’s Deadliest Dolphins: Spy in the Pod 72 Cutest Animals Trek: Spy of the Lions: Spy in the Den Growing Up Wild Wildebeest Bears: Spy in the Woods Baby Animals in the Wild Africa’s Deadliest Penguins: Spy in the Hidden Kingdoms Leopard Fight Club Huddle Terra Animal Fight Night Blackfish Ghost of the Mountain Peculiar Pets Shark Virunga Race of LIfe The Lion in Your Living 72 Dangerous Animals: Wild Ones Room Asia David Attenborough’s A Dog’s Life 72 Dangerous Animals: Natural Curiosities Tyke: Elephant Outlaw America Earth & Nature : Space: History: Planet Earth II Alien Contact: Outer NOVA: Secrets of Noah’s Planet Earth Space Ark Blue Planet NOVA: Earth’s Rocky Start The Vietnam War Frozen Planet Into the Inferno The Pyramid Code Planet Earth: As You’ve The Real Death Star Vikings Unearthed Never Seen It Edge of the Universe WWII in Colour A Plastic Ocean Horizon: Secrets of the Untold Histories of the Earth’s Natural Wonders Solar System United States Mission Blue The Inexplicable Universe Nazi Mega Weapons World’s Worst Disasters The Beginning and End of 9/11: Truths, Lies & Nature’s Weirdest Events the Universe Conspiracy Nature’s Great Events Horizon: Supermassive Nazi Megastructures Weird Wonders of the Black Holes Auschwitz: The Nazis and World Orbit the Final Solution Forces of Nature In Search for Life in Space D-Day Desperate Hours: The Royal House of Witnesses & Survivors Presidents: Windsor Full Force Nature How to Win the US Tornado Hunters Presidency Dinosaurs: The Wheelchair President Raising the Dinosaur Giant JFK: The Making of a Horizon Dinosaurs: The President Hunt for Life Meet the Trumps: From Dino Hunt Immigrant to President HomeschoolHideout.com Please do not share or reproduce. -

17-06-27 Full Stock List Drone

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST - JUNE 2017 (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €17) Amish Glamour (do-CD, 2012, Nitkie Records Patch ten, €17) 1000SCHOEN / AB INTRA Untitled (do-CD, 2014, Zoharum ZOHAR 070-2, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10inch, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2:13 PM Anus Dei (CD, 2012, 213Records 213cd07, €10) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) Speak to me (LP, 2016, Black Truffle BT023, €17.5) 300 BASSES Sei Ritornelli (CD, 2012, Potlatch P212, €15) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth (CD, 1994, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu1, €14) 7JK (SIEBEN & JOB KARMA) Anthems Flesh (CD, 2012, Redroom Records REDROOM 010 CD , €13) 87 CENTRAL Formation (CD, 2003, Staalplaat STCD 187, €8) @C 0° - 100° (CD, 2010, Monochrome -

Nancy Daniels Chief Brand Officer, Discovery & Factual

Nancy Daniels Chief Brand Officer, Discovery & Factual Nancy Daniels is Chief Brand Officer, Discovery & Factual, where she oversees all creative and brand strategy, development, production, multiplatform, communications, marketing and day-to-day operations for Discovery Channel and Science Channel in the U.S. Previously Daniels was President of TLC, where she led the company's flagship female-focused channel, overseeing all aspects of the network's programming, production, development, multiplatform, communications and marketing in the U.S. Under her leadership, TLC has been a top 10 network for women with long-running hit series "Sister Wives," "90 Day Fiancé," "The Little Couple," "My 600-lb Life," "Long Lost Family" and "Outdaughtered," among many others. Among her other recent achievements at TLC, Daniels oversaw the return of beloved home design hit series "Trading Spaces." Beyond programming, in 2016 Daniels launched TLC's powerful brand campaign "I AM," championing empowerment and celebrating peoples' differences. She also oversaw the network's "Give a Little" national multiplatform cause-marketing campaign encouraging viewers to support organizations that help those in need. Also in 2016, Daniels proudly accepted a GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Reality Program for TLC's groundbreaking series "I am Jazz," which follows the life of transgender teen, Jazz Jennings. Daniels previously was EVP, Production & Development at Discovery Channel from 2011-2013, where she played a critical role in driving the network's record-breaking -

Original Television Soundtrack Composed by GEORGE FENTON

original television soundtrack composed by GEORGE FENTON VOLUME 1 FROM POLE TO POLE 01. Planet Earth Prelude 02. The Journey of the Sun 03. Hunting Dogs 04. Elephants in the Okavango CAVES 05. Diving into Darkness 06. Stalactite Gallery 07. Bat Hunt 08. Discovering Deer Cave FRESHWATER 09. Angel Falls 10. River Predation 11. Iguacu 12. The Snow Geese MOUNTAINS 13. The Geladas 14. The Snow Leopard 15. The Karakorum 16. The Earth’s Highest Challenge DESERTS 17. Desert Winds / The Locusts 18. Fly Catchers 19. Namibia - The Lions and the Oryx VOLUME 2 GREAT PLAINS 01. Plains High and Low 02. The Wolf and the Caribou 03. Tibet Reprise / Close SHALLOW SEAS 04. Surfing Dolphins 05. Dangerous Landing 06. Mother and Calf - The Great Journey JUNGLES 07. The Canopy / Flying Lemur 08. Frog Ballet / Jungle Falls 09. The Cordecyps 10. Hunting Chimps SEASONAL FORESTS 11. The Redwoods 12. Fledglings 13. Seasonal Change ICE WORLDS 14. Discovering Antarctica 15. The Humpbacks Bubblenet 16. Everything Leaves but the Emperors 17. The Disappearing Sea Ice 18. Lost in the Storm OCEAN DEEP 19. A School of Five Hundred 20. Giant Mantas 21. Life Near the Surface 22. The Choice is Ours Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne PLANET EARTH as you’ve never seen it before Impala, Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne Bears, Glacier National Park © DCI / Jean-Marc Giboux 01. Planet Earth Prelude 02. The Journey of the Sun 03. Hunting Dogs FROM POLE TO POLE 04. Elephants in the Okavango Wild dogs, Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne Polar bear and cub © Jason C Roberts Giraffes, Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne Great white shark © Simon King 05. -

Claire Berry CV Sept 2016

CLAIRE BERRY Freelance Offline Editor Phone: (07714) 627 526 – E-Mail: [email protected] I am an organised and creative editor with a strong passion for story telling. I enjoy collaborating with producers and directors to produce fun, entertaining, thought-provoking and moving programmes that take viewers on a journey. I am extremely motivated with a hard working ethic and a dedication to any project I undertake. I am proficient using Avid, Final Cut Pro and Adobe Premiere. I have worked across a range of genres including Natural History, Children’s TV, presenter-led adventure, observational documentary and cookery and I’m always keen to diversify my experience by working on a varied range of output. Offline Editor Programme Credits WILDEST EUROPE (WILD WATERS / FORESTS & WOODLANDS) (2 x 1hr) Natural history programmes discovering the wildlife and habitats that span the European continent. Off The Fence for Discovery / Series Producer: Colin Collis / Executive Producer: Alison Bean WILDEST INDONESIA (VOLCANOES / DRAGONS) (2 x 1hr) Natural history programmes about the remote and extreme lands of Indonesia and the animals that live there. Off The Fence for Discovery / Series Producer: Colin Collis / Executive Producer: Alison Bean STRANGE WORLDS: SPOOKLIGHTS (1 x 1 hr) Alex Hannaford travels the globe, investigating claims of the strangest phenomena of our times, while searching for an explanation. Off The Fence for Tern / Producer: Hannah Gibson / Series Producer: Ceri Rowlands / Executive Producer: Alison Bean JOURNEY TO THE CENTRE OF YOUR PLATE Series following the journeys made by Britain’s best-loved foods; from field, farm, harbour and river to supermarket shelves, dinner tables, shops, restaurants and a few very surprising destinations Keo Films for Channel 4 / Series Producer: Michelle Crowley / Executive Producer: Matt Cole WILD INDIA (WESTERN GHATS / THAR DESERT) (2 x 1 hr) Natural history programmes exploring what makes these areas unique & how the extreme climate impacts the life forms there. -

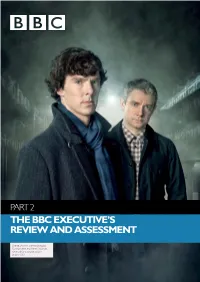

BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2012

PART 2 THE BBC EXECUTIVE’S REVIEW AND ASSESSMENT Drama Sherlock, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, returned for a second series in January 2012. CONTENTS AND SUBJECT INDEX Part 2 BBC Executive contents Managing the business Overview 2-28 Chief Operating Officer’s review 2-1 Director-General’s introduction 2-29 Working together 2-2 Understanding the BBC’s finances Governance 2-4 Performance by service 2-40 Executive Board 2-8 Television 2-42 Risks and opportunities 2-9 Radio 2-44 Governance report 2-10 News 2-47 Remuneration report 2-11 Future Media 2-52 Audit Committee report 2-12 Nations & Regions 2-55 Fair trading report Delivering our strategy Managing our finances 2-14 Distinctiveness and quality 2-58 Chief Financial Officer’s review 2-15 The best journalism in the world 2-59 Summary financial performance 2-16 Inspiring knowledge, music 2-60 Financial overview and culture 2-68 Collecting the licence fee 2-17 Ambitious drama and comedy 2-69 Looking forward with confidence 2-20 Outstanding children’s content 2-70 Auditor’s report 2-21 Content that brings the nation 2-71 Glossary and communities together 2-72 Contact us/More information 2-22 Value for money 2-23 Serving all audiences 2-26 Openness and transparency Subject Index Part 1 Part 2 Board remuneration 1-9/1-32 2-48 Commercial strategy 1-8 2-36 Complaints 1-3/1-19 2-55 Delivering Quality First 1-4/1-6 2-14 Digital switchover – 2-25 Distribution 1-17 2-25 Editorial priorities – 2-14 Editorial standards 1-3/1-18 2-38 Efficiency 1-6 2-59/2-61 Equality and diversity -

2015 Southeast Alaska Discovery Center Spring Schedule 2015 Southeast Alaska Discovery Center Spring Schedule

2015 Southeast Alaska Discovery Center Spring Schedule 2015 Southeast Alaska Discovery Center Spring Schedule The Southeast Alaska Discovery Cen ter January 2, 2015 operated by the US Forest Service January 23, 2015 February 13, 2015 is excited to announce our Spring 2015 12:15 Film: Frozen Planet Ends of the Earth 12:30 Film: National Parks America’s Best Idea 12:30 Film: National Parks America’s Best winter events schedule. 1:15 Film: Theodore Roosevelt Idea Great Nature American Experience Going Home All programs are free and open to 2:30 Film: Salmon Running the Gaunt let 5:30 Film: America’s Deadly Volcano Katami 2:30 Film: Life on Fire The Surprise Salm on the public. 3:30 Film: The West Fight No More Forever 6:30 Film: The West The People 3:30 Film: The West Speck of Future 5:30 Film: Leave it to Beaver 5:30 Film: The Greely Expedition Schedule is subject to change. 7:00 Speaker: Paleolimnology Lake Harriet 7:00 Speaker: Ketchikan High School Oce an Additional events may be oered January 9, 2015 Hunt and Water Quality with Science Bowl Competition with Julie throughout the winter. Christopher Done r Landwehr Visit our website http://alaskacenters.gov/ 12:30 Film: John Muir in the New World January 30, 2015 February 20, 2015 ketchikan.cfm or request ema-il updates by 2:00 Film: Life on Fire: Volcanoes Doctors contacting [email protected] 3:00 Film: The West the People 12:30 Film: 60 Degrees Nort h 12:30 Film: The National Parks America’s Best 4:45 Film: Your Inner Fish 2:00 Film: Braving Alaska Idea Morning of Creation 5:30 Film: Becoming Human First Steps Education box check in/out, information 3:30 Film: The West Death Runs Riot 2:30 Film: The Greely Expedition 7:00 Speaker: A day in the Life of Ketchikan requests, eld trips and map sales will be 3:30 Film: The West Geography of Hope with Susan Hoyt 5:30 Film: Your Inner Monkey oered during our business hours: 7:00 Film: Tracing Roots with Dolores 5:45 Film: Great Migrations Born to Mo ve Fridays Noon to 8 p.m. -

Kate Hopkins

The Interview I couldn’t actually see where my hand was relative to the lion, but I had Tim in the back of the car saying, ‘You’re fine, you’re fine, he won’t bite it off…’ Kate Hopkins NIGEL JOPSON meets Sir David Attenborough’s favourite sound editor ate Hopkins has worked on some of I get a mute picture — there is usually no sound before it goes into a mix. Basically, what I do is the most prestigious natural history on it at all. What I do is to create layers of audio make a whole lot of decisions about what you TV ever: Blue Planet, Wolves at Our which articulate the picture — to make it sound are going to hear. KDoor, Planet Earth (for which she won as realistic as it possibly can — so the viewer a Primetime Emmy), Life in the Undergrowth, feels as if they are actually ‘there’. If the shot is In movie terms, then, your role is that of a Great Migrations, Life, Human Planet and of the Serengeti, one single piece of audio will sound designer: the nature documentaries Frozen Planet (for which she was awarded a not do it. You need layers: the sound of insects, you work on have very little production BAFTA in 2012). The top four most-watched TV the sound of wind, trees… if there’s a storm you sound recorded ‘on set’! programmes in the UK in 2017 were the four need rain. Rain is not just one sound, you can We do receive ‘wild’ tracks recorded on episodes of Blue Planet II, with around 13-14 hear large drops nearby, and a general more location. -

The 2020 Investor Day Programming Fact Sheet

THE 2020 INVESTOR DAY PROGRAMMING FACT SHEET ©Disney Today at The Walt Disney Company’s Investor Day event, Lucasfilm President Kathleen Kennedy announced an impressive number of exciting Disney+ series and new feature films destined to expand theStar Wars galaxy like never before. Introducing the Disney+ slate, Kennedy said, “We have a vast and expansive timeline in the Star Wars mythology spanning over 25,000 years of history in the galaxy—with each era being a rich resource for storytelling. Now with Disney+, we can explore limitless story possibilities like never before and fulfill the promise that there is truly a Star Wars story for everyone.” Among the 10 projects announced for Disney+ is “Obi-Wan Kenobi,” starring Ewan McGregor, with Hayden Christensen returning as Darth Vader, in what Kennedy called, “the rematch of the century.” Also announced are two new series from Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni, off-shoots of the multiple Emmy®-winning “The Mandalorian.” “Rangers of the New Republic” and “Ahsoka,” a series featuring the fan-favorite character Ahsoka Tano, will take place in “The Mandalorian” timeline. Kennedy announced that the next Star Wars feature film, releasing in December 2023, will be “Rogue Squadron,” which will be directed by Patty Jenkins of the “Wonder Woman” franchise. In July 2022, the next installment of the “Indiana Jones” franchise premieres, starring Harrison Ford, who reprises his iconic role. The film is directed by James Mangold. Following are the announced projects, listed in announcement order under the Disney+ and feature film headers: DISNEY+ Ahsoka After making her long-awaited, live-action debut in “The Mandalorian,” Ahsoka Tano’s story, written by Dave Filoni, will continue in a limited series, Ahsoka, starring Rosario Dawson and executive produced by Dave Filoni and Jon Favreau. -

Class 6 Spring 2021 Frozen Kingdom

Class 6 Spring 2021 Frozen Kingdom Topic Overview Welcome to the planet’s coldest lands. Vast wilds and hostile territories; incredibly beautiful, yet often deadly. Take shelter from the elements or fall prey to icy winds and the deepest chill. Trek bravely and valiantly across treacherous terrain to the ends of the Earth, treading deep in snow or being pulled by a team of mighty sled dogs. Be alert, for magnificent mammals roam these lands, sometimes hungry or fresh for a fight. Perhaps a hungry polar bear or an Arctic fox is hunting rodents, as swift as the wind. We’ll learn what is needed for a polar expedition as we read Shackleton’s Journey. Using globes and maps, we’ll identify the polar regions, comparing the Arctic and Antarctic. We’ll also think about how we can protect the polar environment. Then, we’ll investigate the tragic story of the RMS Titanic, and find out about the people on board. When we’re more familiar with the polar regions, we’ll write exciting stories, poems and diary entries from the perspective of brave explorers. Researching our favourite polar animals will be fun, and we’ll create animal artwork inspired by the Inuit people. We’ll experiment with digital photography and create amazing effects using paints and dyes. English Newspaper report; Persuasive Speech; Description; Poetry; Argument/Debate; Non-chronological report; Diary; Film trailer; Short narrative; Letter; Obituary Mathematics Fractions, Geometry: Position and Direction, Decimals, Percentages; Algebra; Measuring: Converting Units; Measurement: Perimeter, Area and Volume; Ratio Science Living things and their habitats; Animals, including Humans RE What do religions say to us when life gets hard? What difference does the resurrection make to Christians? (Salvation) Humanities H – Exploration in the 1900s; Research the Titanic G – Use globes and atlases for polar regions and other significant geographical features of the world; Identify similarities and differences between the Arctic and Antarctic Music Compose a piece of music based on a theme (e.g. -

Planet Earth II in Concert’ Featuring Breathtaking Footage and Live Music in Partnership with BBC Earth

Holland America Line Premieres ‘Planet Earth II in Concert’ Featuring Breathtaking Footage and Live Music in Partnership with BBC Earth March 12, 2018 New multimedia production takes guests on a musical adventure, revealing the planet from a new perspective with the latest ‘BBC Earth' production Seattle, Wash., Mar. 12, 2018 — Following the success of the highly acclaimed "Frozen Planet in Concert" that was produced in partnership with BBC Earth, Holland America Line is debuting "Planet Earth II in Concert" on nearly all ships in the fleet. Combining live music with a backdrop of breathtaking footage from the new, award-winning BBC Earth television series "Planet Earth II," the exclusive show immerses guests in the most spectacular landscapes and habitats on Earth, bringing them eye-to-eye with the animals on screen. "Planet Earth II in Concert" is presented through Holland America Line's partnership with BBC Earth, where world-class education and entertainment are brought onboard through behind-the-scenes films and live multimedia shows — in addition to special feature cruises with masterclass presentations from the television teams that work behind scenes on the programs. "Our partnership with BBC Earth has been an extraordinary journey to all corners of the globe, and we can't wait to take our guests into the world of ‘Planet Earth II' with this stunning, new live concert," said Orlando Ashford, president of Holland America Line. "‘Frozen Planet in Concert' has been one of our most popular shows, and ‘Planet Earth II' will be the perfect