CHAPTER 2 Fragmentation and Interpretation of Spectra 2.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covalent and Noncovalent Intermediates of an NAD Utilizing Enzyme, Human CD38

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Chemistry & Biology Article Covalent and Noncovalent Intermediates of an NAD Utilizing Enzyme, Human CD38 Qun Liu,1 Irina A. Kriksunov,1 Hong Jiang,2 Richard Graeff,4 Hening Lin,2 Hon Cheung Lee,4,5,* and Quan Hao1,3,5,* 1MacCHESS, Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source 2Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology 3School of Applied & Engineering Physics Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA 4Department of Pharmacology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 5Department of Physiology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China *Correspondence: [email protected] (H.C.L.), [email protected] (Q.H.) DOI 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.08.007 SUMMARY These processes are known to have important cellular and physiological functions in DNA repair (Lombard et al., 2005; Enzymatic utilization of nicotinamide adenine dinu- Michan and Sinclair, 2007), transcriptional regulation (Blander cleotide (NAD) has increasingly been shown to have and Guarente, 2004), cellular differentiation and proliferation, fundamental roles in gene regulation, signal trans- aging (Hassa et al., 2006), and calcium signaling (Lee, 2001; duction, and protein modification. Many of the pro- Lee et al., 1999). cesses require the cleavage of the nicotinamide moi- Although NAD is a substrate for multiple enzymes, the initial ety from the substrate and the formation of a reactive steps of the cleavage and release of the nicotinamide moiety are conserved. The nature of the subsequent intermediates intermediate. Using X-ray crystallography, we show formed, on the other hand, has been a widely debatable issue. -

Recommending Hartree-Fock Theory with London- Dispersion and Basis

Recommending Hartree-Fock Theory with London- Dispersion and Basis-Set-Superposition Corrections for the Optimization or Quantum Refinement of Protein Structures Lars Goerigk,a* Charles A. Collyer,b Jeffrey R. Reimersc,d* a School of Chemistry, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia b School of Molecular Bioscience, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia c School of Physics and Advanced Materials, The University of Technology, Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia d Centre for Quantum and Molecular Structure, College of Sciences, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China 1 ABSTRACT We demonstrate the importance of properly accounting for London-dispersion and basis-set superposition-error (BSSE) in quantum-chemical optimizations of protein structures, factors that are often still neglected in contemporary applications. We optimize a portion of an ensemble of conformationally flexible lysozyme structures obtained from highly accurate X-ray crystallography data that serves as a reliable benchmark. We not only analyze root-mean-square deviations from the experimental Cartesian coordinates, but, for the first time, also demonstrate how London-dispersion and BSSE influence crystallographic R factors. Our conclusions parallel recent recommendations for the optimization of small gas-phase peptide structures made by some of the present authors: Hartree-Fock theory extended with Grimme’s recent dispersion and BSSE corrections (HF-D3-gCP) is superior to popular density-functional-theory (DFT) approaches. Not only are statistical errors on average lower with HF-D3-gCP, but also its convergence behavior is much better. In particular, we show that the BP86/6-31G* approach should not be relied upon as a black-box method, despite its widespread use, as its success is based on an unpredictable cancellation of errors. -

A Facile Approach to Prepare Multiple Heteroatom-Doped Carbon

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A Facile Approach to Prepare Multiple Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Materials from Imine- Received: 17 November 2017 Accepted: 19 February 2018 Linked Porous Organic Polymers Published: xx xx xxxx Juan Yang, Min Xu, Jingyu Wang , Shangbin Jin & Bien Tan In this paper, we proposed a new strategy to prepare multiple heteroatom doped (N, P-doped) porous carbon materials with high surface area of ~1,535 m2 g−1 simply by pyrolysis of imine-linked porous organic polymers (POPs) synthesized via Schif base condensation. The strategy is simple without any post-processing and various heteroatoms could be involved. Scanning electron microscopy, Raman spectra, Nitrogen gas adsorption-desorption, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy have been used to characterize the morphology, the structure and the composition of the materials. The multiple heteroatom doped porous carbon materials also display high electrocatalytic performance as exampled by the application in oxygen reduction, which showed the catalyst favors 4-electron transfer during the process, along with superior stability and higher tolerance to methanol as compared to the Pt/C. These results indicate the present method is promising for the preparation of multi-heteroatom doped carbon materials in the application of electrocatalysis. Porous organic polymers (POPs) are a type of organic polymers with large surface area, tunable skeleton and high stability1,2. Tey have attracted extensive attentions for broad applications in the felds of gas storage and separations, catalysis and energy storage3–5. Tere are many methodologies reported for the preparation of porous polymers6–10. Among them, Schif base reaction is one of the most versatile ways due to the facile, one-pot, catalyst-free, quantitative synthesis11. -

FIRE-SAFE POLYMERS and POLYMER COMPOSITES September 2004 6

DOT/FAA/AR-04/11 Fire-Safe Polymers and Polymer Office of Aviation Research Washington, D.C. 20591 Composites September 2004 Final Report This document is available to the U.S. public through the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), Springfield, Virginia 22161. U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturer's names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. This document does not constitute FAA certification policy. Consult your local FAA aircraft certification office as to its use. This report is available at the Federal Aviation Administration William J. Hughes Technical Center’s Full-Text Technical Reports page: actlibrary.act.faa.gov in Adobe Acrobat portable document format (PDF). Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT/FAA/AR-04/11 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date FIRE-SAFE POLYMERS AND POLYMER COMPOSITES September 2004 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Huiqing Zhang 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Polymer Science and Engineering University of Massachusetts Amhurst, MA 01003 11. Contract or Grant No. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Office of Aviation Research 14. -

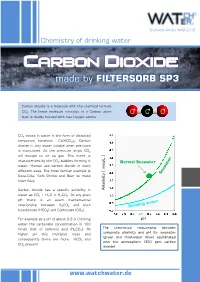

Carbon Dioxide - Made by FILTERSORB SP3

Technical Article MAR 2015 Chemistry of drinking water Carbon dioxide - made by FILTERSORB SP3 Carbon dioxide is a molecule with the chemical formula CO2. The linear molecule consists of a Carbon atom O C O that is doubly bonded with two Oxygen atoms. CO2 exists in water in the form of dissolved temporary hardness Ca(HCO3)2. Carbon dioxide is only water soluble when pressure is maintained. As the pressure drops CO2 will escape to air as gas. This event is characterized by the CO2 bubbles forming in /L ] Normal Seawater water. Human use carbon dioxide in many meq different ways. The most familiar example is Coca-Cola, Soft Drinks and Beer to make them fizzy. Carbon dioxide has a specific solubility in [ Alkalinity water as CO2 + H2O ⇌ H2CO3. At any given pH there is an exact mathematical relationship between H2CO3 and both bicarbonate (HCO3) and Carbonate (CO3). For example at a pH of about 9.3 in Drinking pH water the carbonate concentration is 100 The theoretical relationship between times that of carbonic acid (H2CO3). At carbonate alkalinity and pH for seawater higher pH this multiplier rises and (green and freshwater (blue) equilibrated consequently there are more HCO and 3 with the atmosphere (350 ppm carbon CO present 3 dioxide) www.watchwater.de Water ® Technology FILTERSORB SP3 WATCH WATER & Chemicals Making the healthiest water How SP3 Water functions in human body ? Answer: Carbon dioxide is a waste product of the around these hollow spaces will spasm and respiratory system, and of several other constrict. chemical reactions in the body such as the Transportation of oxygen to the tissues: Oxygen creation of ATP. -

A Complete Guide to Benzene

A Complete Guide to Benzene Benzene is an important organic chemical compound with the chemical formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. As it contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms, benzene is classed as a hydrocarbon. Benzene is a natural constituent of crude oil and is one of the elementary petrochemicals. Due to the cyclic continuous pi bond between the carbon atoms, benzene is classed as an aromatic hydrocarbon, the second [n]- annulene ([6]-annulene). It is sometimes abbreviated Ph–H. Benzene is a colourless and highly flammable liquid with a sweet smell. Source: Wikipedia Protecting people and the environment Protecting both people and the environment whilst meeting the operational needs of your business is very important and, if you have operations in the UK you will be well aware of the requirements of the CoSHH Regulations1 and likewise the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) in the US2. Similar legislation exists worldwide, the common theme being an onus on hazard identification, risk assessment and the provision of appropriate control measures (bearing in mind the hierarchy of controls) as well as health surveillance in most cases. And whilst toxic gasses such as hydrogen sulphide and carbon monoxide are a major concern because they pose an immediate (acute) danger to life, long term exposure to relatively low level concentrations of other gasses or vapours such as volatile organic compounds (VOC) are of equal importance because of the chronic illnesses that can result from that ongoing exposure. Benzene, a common VOC Organic means the chemistry of carbon based compounds, which are substances that results from a combination of two or more different chemical elements. -

Chemical Formula

Chemical Formula Jean Brainard, Ph.D. Say Thanks to the Authors Click http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (No sign in required) AUTHOR Jean Brainard, Ph.D. To access a customizable version of this book, as well as other interactive content, visit www.ck12.org CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based collaborative model termed the FlexBook®, CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide an adaptive environment for learning, powered through the FlexBook Platform®. Copyright © 2013 CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org The names “CK-12” and “CK12” and associated logos and the terms “FlexBook®” and “FlexBook Platform®” (collectively “CK-12 Marks”) are trademarks and service marks of CK-12 Foundation and are protected by federal, state, and international laws. Any form of reproduction of this book in any format or medium, in whole or in sections must include the referral attribution link http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (placed in a visible location) in addition to the following terms. Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Com- mons from time to time (the “CC License”), which is incorporated herein by this reference. -

Comparison of the Characteristic Mass Fragmentations of Phenethylamines and Tryptamines by Electron Ionization Gas Chromatograph

applied sciences Article Comparison of the Characteristic Mass Fragmentations of Phenethylamines and Tryptamines by Electron Ionization Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry, Electrospray and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry Bo-Hong Chen, Ju-Tsung Liu, Hung-Ming Chen, Wen-Xiong Chen and Cheng-Huang Lin * Department of Chemistry, National Taiwan Normal University, 88 Sec. 4 Tingchow Road, Taipei 11677, Taiwan; [email protected] (B.-H.C.); [email protected] (J.-T.L.); [email protected] (H.-M.C.); [email protected] (W.-X.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-2-7734-6170; Fax: +886-2-2932-4249 Received: 18 April 2018; Accepted: 19 June 2018; Published: 22 June 2018 Abstract: Characteristic mass fragmentation of 20 phenethylamine/tryptamine standards were investigated and compared by means of matrix assisted laser desorption/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI/TOFM), gas chromatography–electron ionization–mass spectrometry (GC-EI/MS) and liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry (LC-ESI/MS) + methods. As a result, three characteristic peaks ([M] and fragments from the Cβ-Cα bond breakage) were found to be unique and contained information useful in identifying 2C series compounds based on the GC-EI/MS method. We found that the protonated molecular ion ([M+H]+) and two types of fragments produced from the α-cleavage and β-cleavage processes were useful mass spectral information in the rapid screening and confirmation of phenethylamine and tryptamine derivatives when ESI/MS and MALDI/TOFMS methods were applied. This assay was successfully used to determine samples that contain illicit drugs. Keywords: phenethylamine; tryptamine; MALDI/TOFMS; GC-EI/MS; LC-ESI/MS 1. -

Introduction, Formulas and Spectroscopy Overview Problem 1

Chapter 1 – Introduction, Formulas and Spectroscopy Overview Problem 1 (p 12) - Helpful equations: c = ()() and = (1 / ) so c = () / ( ) c = 3.00 x 108 m/sec = 3.00 x 1010 cm/sec a. Which photon of electromagnetic radiation below would have the longer wavelength? Convert both values to meters. -1 = 3500 cm = 4 x 1014 Hz = (1/) = (c / ) = (1/ ) = (3.0 x 108 m/s) / (4 x 1014 s-1) = (1/ cm-1)(1 m/100 cm) = 2.9 x 10-6 m = 7.5 x 10-7 m = longer wavelength = lower energy b. Which photon of electromagnetic radiation below would have the higher frequency? Convert both values to Hz. = 400 cm-1 = 300 nm = (1/ ) = 1/ [(400 cm-1)(100 cm / 1 m)] = (c/) 8 -5 9 = 2.5 x 10-5 m = (3.0 x 10 m/s) / (2.5 x 10 nm)(1m / 10 nm) v = (3.0 x 108 m/s) / (300 nm)(1m / 109 nm) = (c/) v = 1.0 x x 1015 s-1 = (3.0 x 108 m/s) / (2.5 x 10-5 m) v = 1.2 x 1013 s-1 higher frequency c. Which photon of electromagnetic radiation below would have the smaller wavenumber? Convert both values to cm-1. = 1 m = 6 x 1010 Hz = (1 / ) -1 = ( / c) = (1 / 1m) = 1 m-1 100 cm = 100 cm-1 100 cm-1 -1 = (6 x 1010 s-1 / 3.0 x 108 m/s) = 200 m-1 -1 1 m -1 = 20,000 cm smaller wavenumber 1 m Problem 2 (p 14) - Order the following photons from lowest to highest energy (first convert each value to kjoules/mole). -

Coupling Gas Chromatography to Mass Spectrometry

Coupling Gas Chromatography to Mass Spectrometry Introduction The suite of gas chromatographic detectors includes (roughly in order from most common to the least): the flame ionization detector (FID), thermal conductivity detector (TCD or hot wire detector), electron capture detector (ECD), photoionization detector (PID), flame photometric detector (FPD), thermionic detector, and a few more unusual or VERY expensive choices like the atomic emission detector (AED) and the ozone- or fluorine-induce chemiluminescence detectors. All of these except the AED produce an electrical signal that varies with the amount of analyte exiting the chromatographic column. The AED does that AND yields the emission spectrum of selected elements in the analytes as well. Another GC detector that is also very expensive but very powerful is a scaled down version of the mass spectrometer. When coupled to a GC the detection system itself is often referred to as the mass selective detector or more simply the mass detector. This powerful analytical technique belongs to the class of hyphenated analytical instrumentation (since each part had a different beginning and can exist independently) and is called gas chromatograhy/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Placed at the end of a capillary column in a manner similar to the other GC detectors, the mass detector is more complicated than, for instance, the FID because of the mass spectrometer's complex requirements for the process of creation, separation, and detection of gas phase ions. A capillary column is required in the chromatograph because the entire MS process must be carried out at very low pressures (~10-5 torr) and in order to meet this requirement a vacuum is maintained via constant pumping using a vacuum pump. -

Mechanism of the Cooperative Si–H Bond Activation at Ru–S Bonds† Cite This: Chem

Chemical Science View Article Online EDGE ARTICLE View Journal | View Issue Mechanism of the cooperative Si–H bond activation at Ru–S bonds† Cite this: Chem. Sci.,2015,6,4324 a a ab b Timo Stahl, Peter Hrobarik,´ * C. David F. Konigs,¨ Yasuhiro Ohki, Kazuyuki Tatsumi,b Sebastian Kemper,a Martin Kaupp,a Hendrik F. T. Klare*a and Martin Oestreich*a The nature of the hydrosilane activation mediated by ruthenium(II) thiolate complexes of type [(R3P)- + F À Ru(SDmp)] [BAr 4] is elucidated by an in-depth experimental and theoretical study. The combination of various ruthenium(II) thiolate complexes and tertiary hydrosilanes under variation of the phosphine ligand and the substitution pattern at the silicon atom is investigated, providing detailed insight into the activation mode. The mechanism of action involves reversible heterolytic splitting of the Si–H bond across the polar Ru–S bond without changing the oxidation state of the metal, generating a ruthenium(II) hydride and sulfur-stabilized silicon cations, i.e. metallasilylsulfonium ions. These stable yet highly reactive adducts, which serve as potent silicon electrophiles in various catalytic transformations, are fully Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. characterized by systematic multinuclear NMR spectroscopy. The structural assignment is further verified by successful isolation and crystallographic characterization of these key intermediates. Quantum- chemical analyses of diverse bonding scenarios are in excellent agreement with the experimental findings. Moreover, the calculations reveal that formation of the hydrosilane adducts proceeds via barrierless electrophilic activation of the hydrosilane by sterically controlled h1 (end-on) or h2 (side-on) coordination of the Si–H bond to the Lewis acidic metal center, followed by heterolytic cleavage of the Received 21st March 2015 Si–H bond through a concerted four-membered transition state. -

FOCUS REVIEW Transition Metal Mediated Cleavage of C-C Bonds

FOCUS REVIEW Transition Metal Mediated Cleavage of C-C Bonds in Aromatic Rings Martin Jakoobi,[a] and Alexey G. Sergeev*[a] [a] Title(s), Initial(s), Surname(s) of Author(s) including Corresponding Author(s) Department Institution Address 1 E-mail: [b] Title(s), Initial(s), Surname(s) of Author(s) Department Institution Address 2 Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of For internalthe document. use,((Please please delete dothis textnot if notdelete. appropriate)) Submitted_Manuscript FOCUS REVIEW Abstract: Metal-mediated cleavage of aromatic C-C bonds has a 1.2. Challenges in metal mediated cleavage of aromatic C-C range of potential synthetic applications: from direct coal liquefaction bonds to synthesis of natural products. However, in contrast to the activation of aromatic C-H bonds, which has already been widely In contrast to activation of aromatic C-H bonds, which is now studied and exploited in diverse set of functionalization reactions, widely used in organic synthesis, activation of aromatic C-C cleavage of aromatic C-C bonds is still Terra Incognita. This focus bonds is still a challenging and largely unexplored area.[1, 8] review summarizes the recent progress in this field and outlines key Activation of strong aromatic C-C bonds requires harsh reaction challenges to be overcome to develop synthetic methods based on conditions, and occurs with poor chemoselectivity (C-H bonds this fundamental organometallic transformation. are activated preferentially) and regioselectivity (different kinds of aromatic C-C bonds can be activated indiscriminately), which limits synthetic applications of this promising transformation. The 1.